Something I’ve always loved about works of Japanese narrative art is how hands-off they can often be in terms of structured writing, instead focusing on thematic resonance driven by atmosphere, aesthetics, and world-building. It’s a type of storytelling that begs the audience to jump into a ride blind and allow themselves to be sucked up into the unexplained, which isn’t always the easiest thing to do when a story fails to offer any substantial character or plot hooks.

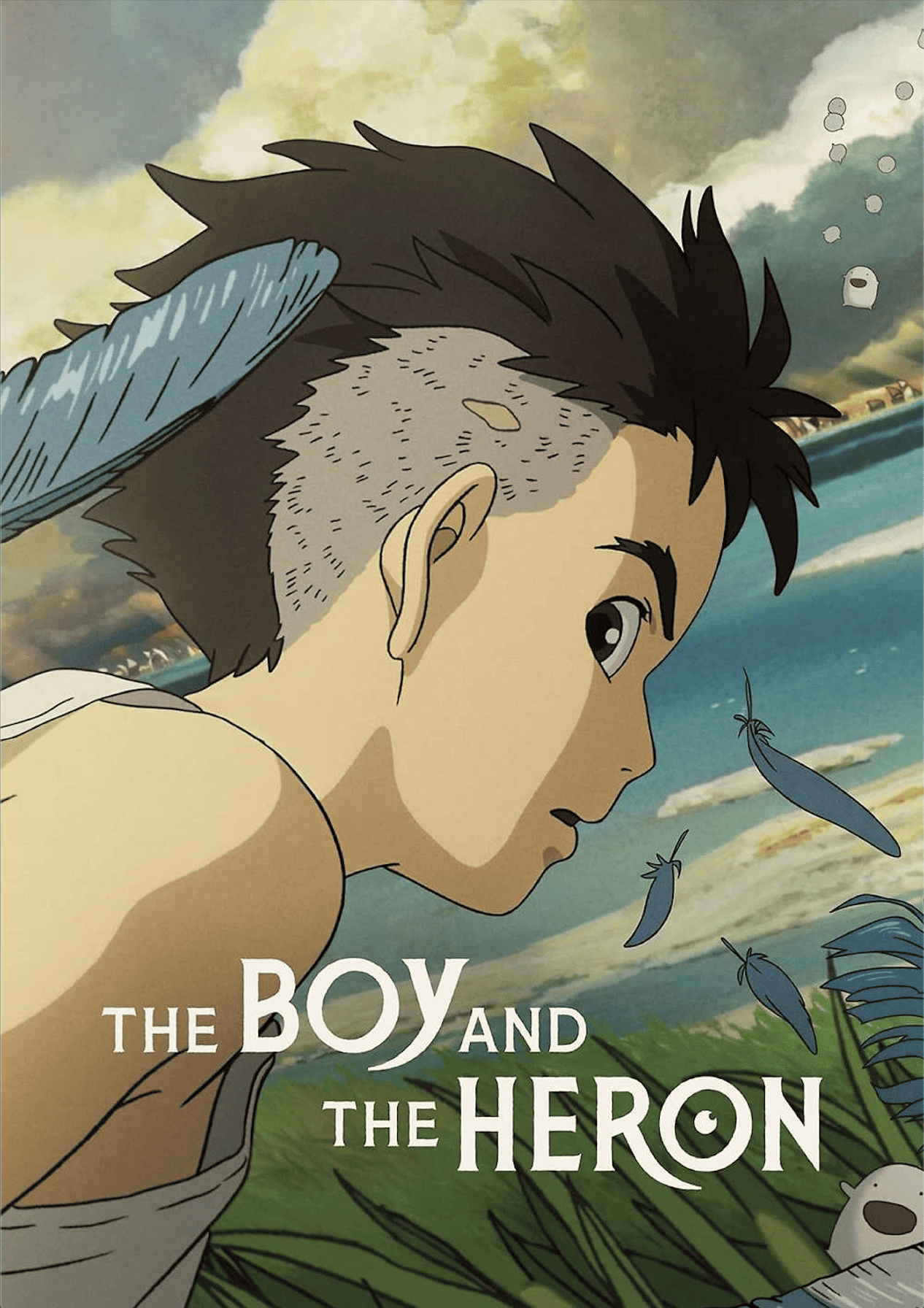

Hayao Miyazaki’s latest film, The Boy and the Heron follows a similar storytelling philosophy, and because of that, everything I loved about the film is the exact kind of thing someone else may perceive as it lacking in substance. The film follows a young teenager named Mahito, who finds himself caught up in a familial legacy of supernatural magic that challenges his inclination to change as his life is turned upside down by the death of his mother. After his new stepmother is dragged into a strange world of his grandfather’s creation, Mahito must dare entering this unknown world to save her before it’s too late.

What sounds like a pretty standard fantasy adventure romp is something much more challenging. The film deals in very weighty and conceptual ideas that go mostly unexplained, their meaning something that has to be inferred against what the story is presenting thematically. Mahito’s ‘familial legacy’ is the dominance over a magical realm that is shared by both the living and the dead, one that’s been growing ever more turbulent with the aging of its master, Mahito’s grandfather. However, this world isn’t conventionally made up and acts as a playground in which the film is able to play around with its overarching theme of growing through acceptance. Weird yet captivating visuals of death, life, and oceanic travel populate this world run by pelicans and parakeets hungry for human flesh.

The film’s tone is especially more mature than what one might expect if their experience with Ghibli films follow the family-friendly hits. There’s quite a bit of rumination on death, the cycle of living, and some dark imagery that doesn’t necessarily bring the entire project down into a depressive slog, but does give it a bit of unexpected darkness to help elevate the narrative’s overall message.

The magical surreality of the world between is backdropped against a Japan just coming out of the Second World War, where change is consuming the nation, and Mahito himself is being faced with it as his family alters significantly yet still wears the skin of what he once knew. It’s easy to thematically understand what the film is saying after some thought, but the film’s lack of true-to-form character writing creates a viewing experience that challenges the audience and asks them to think and interpret their way through the nearly two-hour runtime.

The best example of the film’s hands-off character writing is Mahito himself. His arc isn’t brought to fruition with a moment of gratification the film points at with the subtlety of a shotgun, and the character’s demeanor is reserved and difficult to pierce through. He isn’t a boring character, nor is he one that lacks an easy-to-understand motivation in his actions, but he doesn’t outright show his emotions quite often. He can’t be defined as stoic, but what he can be easily seen as someone who’s grown disassociated with life, his emotionality a victim of constant change he hasn’t been able to grapple with. There is no explicit writing of this, however, just implication, something that can be found with almost every character in the film.

The film’s pacing lacks some direct drive and can feel occasionally lethargic or slow, but it doesn’t take away from the overall viewing experience. While our main characters do have goals that drive the film’s narrative, the way in which those goals are met are through Mahito’s slow yet tense exploration of his grandfather’s world. Characters do at times simply go along with whatever is happening and it can seem somewhat disconcerting, but the heart of this film is Mahito’s growth away from his lethargic care for the living in a world unlike his past, which justifies his curious but never fearful nature.

Aside from the film’s loftier thematic goals, it is also just a masterwork technically. The music, contributed to the film by Joe Hisaishi, is absolutely beautiful. The performances across the board are strong yet subdued, save for Masaki Suda’s performance as the title’s Heron, an incredibly endearing yet slimy character whose pitifulness eventually grows into a genuine care for Mahito, his job of guiding him into his grandfather’s world a quintessential piece of the film’s intrigue. The animation and design of the film’s world are full of the same magical creativity that viewers will have come to expect from Studio Ghibli, this film’s hand-drawn fluidity pushing the bounds of what’s capable with 2D animation in the modern day. It should be noted that the version I saw of the film was the Japanese dub of the film with English subtitles, and found no problems with the films audio design whatsoever.