Marvel was once referred to as the ‘House of Ideas,’ a publisher that the comics industry had sought to mimic because ofhow creatively strong their brand of pop-heroics had been since the early 1960s. Nowadays, the publisher seems to be more of a recycling plant than a place of genuine creative expression as the company continues to prioritize throwback mini-series while ever sterilizing the books in current continuity to fit a certain brandable mold. Granted, many of this series are pretty well-executed for what they’re trying to achieve such as Peter David’s Symbiote Spider-man, a pure treat of a series that is quite a bit of fun, but feels like a wasted return to the past as so much love already exists for that time period.

The promise of bringing back old creators to explore their previous works under new circumstances should prioritize the reclamation of lost ideas, to rectify the mistakes of the past and build something fresh from that’s simply attainable with the trends of modern comics. While Marvel has been keen to phone creators from their golden years, they’ve suspiciously played shy with their exclusively 90s talent. This is understandable as returning to a time period that contains the most critically maligned stories the publisher has ever put to print isn’t something that screams instant sales.

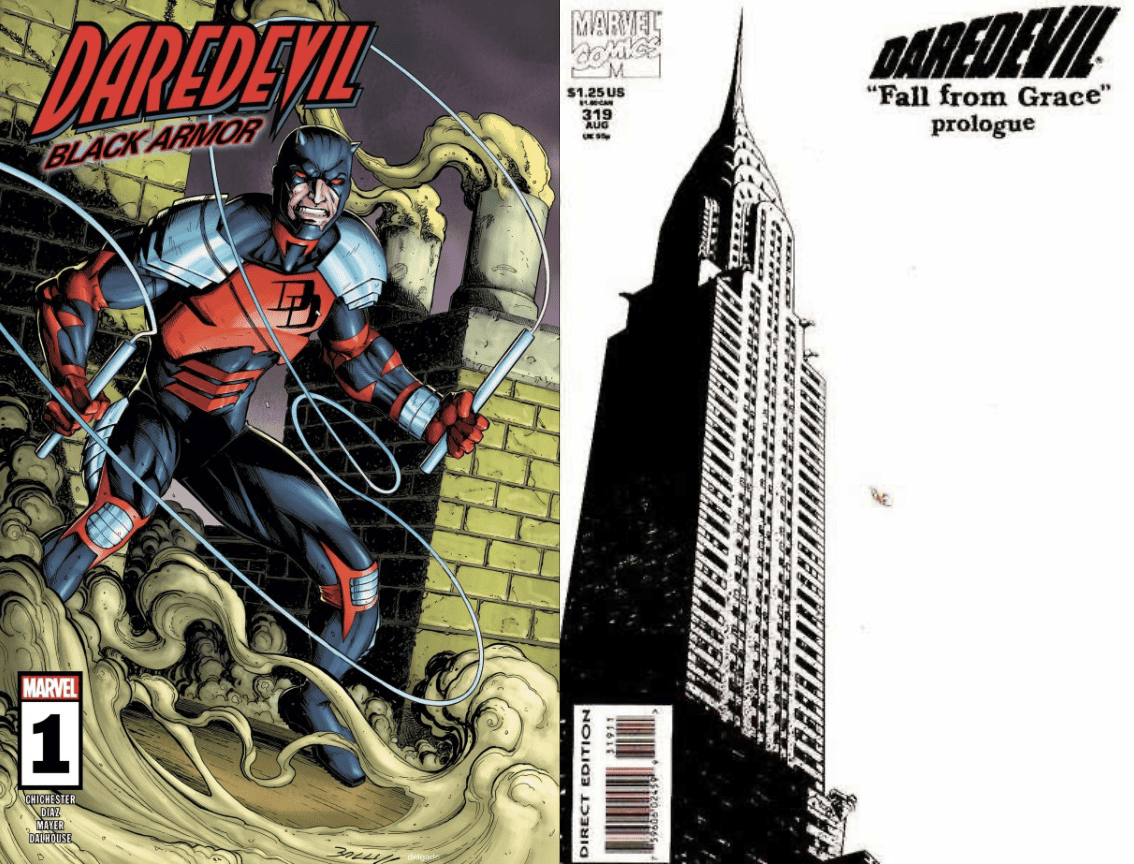

This is why it was such a surprise when Daredevil: Black Armor was announced. This mini-series promised to return readers to Matt Murdock’s most hated time as the Devil of Hell’s Kitchen with none other than the era’s progenitor D.G. Chichester at the book’s helm. This was a ballsy move on Marvel’s part. Daredevil’s ‘Black Armor Era’ isn’t infamous for in the same way Spider-Man’s Clone Saga or the X-Men’s many crossovers were, where convulted continuity and an overflooding market drove readers away. For all of its worth, Chichester’s time on Daredevil was trashed for its simply poor writing and a status quo for Daredevil that didn’t fall in line with what people had expected from the character since Miller’s run.

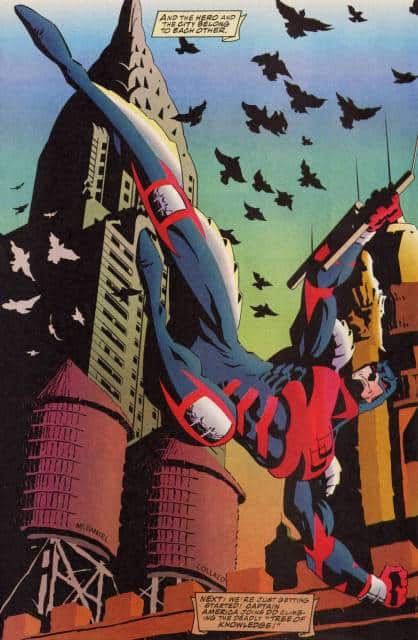

When I say this, I’m not mimicking the claims of my elders. I did my homework on this run, and yeah, it’s a pretty tough go from today’s standard, and when compared to books of the era, even tougher. There are arguments to be made for the time period’s uncomfortable amount of misogyny, as it is something embedded in the source code of Daredevil just as much as Catholicism. However, when paired with poor scripting and plot clarity, it’s a run that screams immaturity on its best days. However, there is a lot of merit to it. There are strong themes bubbling beneath its edge-ridden surface, its visual identity a truly mystifying treat that only a comic of that time period has been able to achieve. This era is most remebered for Matt’s costume switch for a reason, and that’s because regardless of it’s problems on the writing front, it always looked pretty good.

Thus, going into Daredevil: Black Armor #1, I was expecting the worst. I envisioned my time reading Fall From Grace, Chichester’s most notable Daredevil tale before this one and braced for something near unintelligible. Instead, what I found myself doing more often than not was smiling. With age and experience now under his belt, Chichester did the impossible. He had me falling in love with a part of Daredevil’s history that I could barely stand.

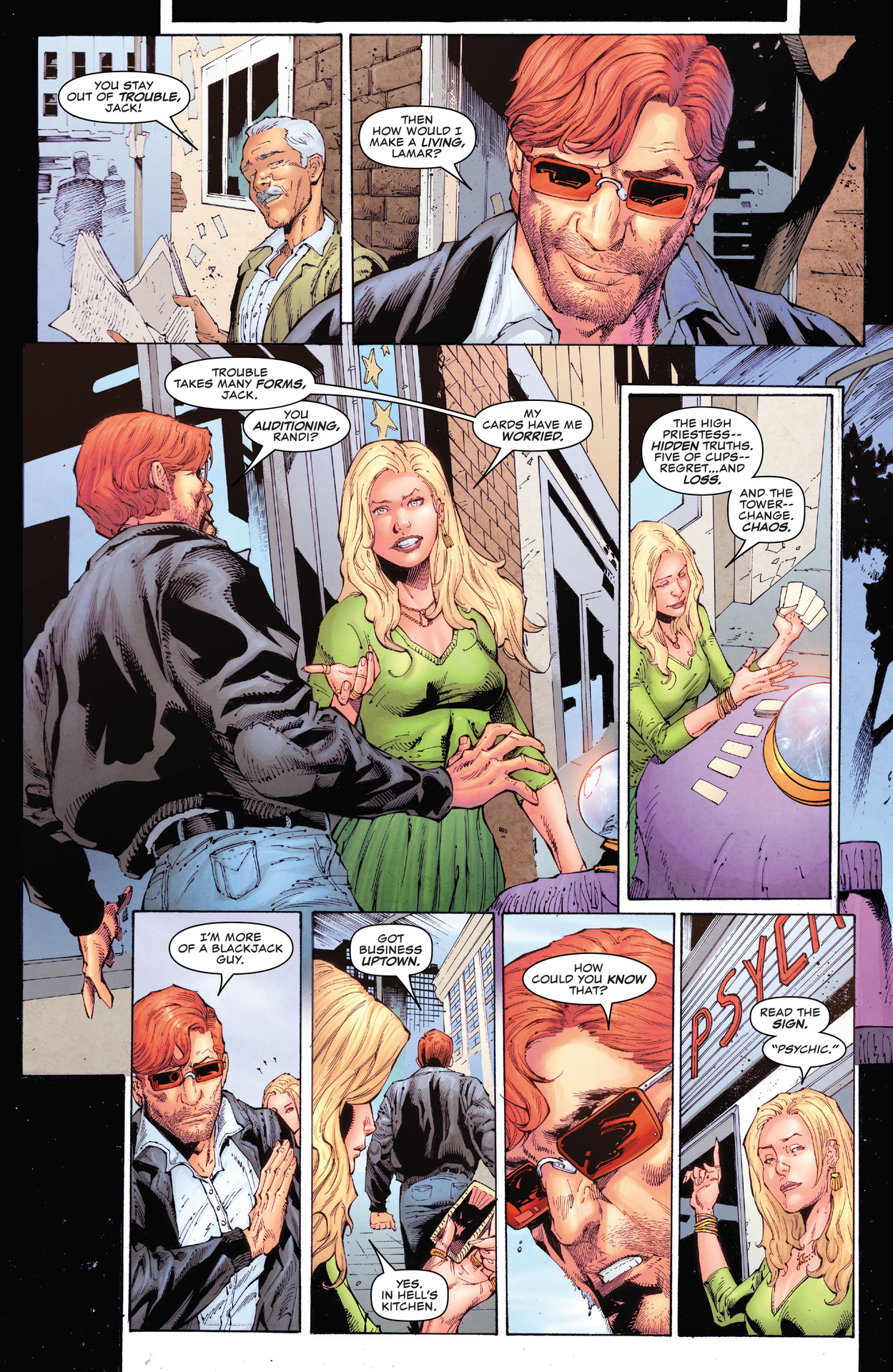

Chichester’s voice for Matt Murdock is unique, yet still innately in line with what I would expect from the character. His cocky but well-meaning manner comes at the behest of him living in a world where everyone assumes him dead. A world in which Daredevil and Matt Murdock, as we would know them, cease to exist. In that space, we get something incredibly fresh that carries with it a new tone for the character that in hindsight is more engrossing than it gets credit for. Without all the baggage of Frank Miller’s influence on the character, what is the book able to be without completely ditching all that was incredibly done with him previously? Well, you get a story that’s able to combine early Daredevil’s superheroics with the dark human drama Miller introduced to the book, which Ann Nocenti subsequently proliferated.

I also found myself really loving the cadence of scripting in this issue. I despise Chichester’s original run’s scripting, and I wear that dislike on my sleeve to emphasize just how great it is here. Chichester’s tone as a scriptor has not left his pen, but his clarity and maturity as a writer absolutely has. While the book does show some age with Matt’s womanizing tendencies, it’s now framed as something within the character that he himself cannot shake as opposed to an omnipresent staple of the book’s natural tone.

There’s an elevated and evolved love for the character here. Chichester goes as far as making reference to current continuity. As an author, he isn’t here to do the curmudgeonly Claremont deed of sticking to his outdated tropes and bashing the modern day, but instead evolving alongside it while maintaining the heart and soul of the past being revisited. It is in every sense the perfect ‘nostalgia trip.’ It’s sleek, it’s new, but offers an atmosphere and narrative perspective on the Daredevil character that only something of its time can. There are times that as artists, creatives, or a passionate person in any field, we will fail. We are all possible at screwing up and finding ourselves in places where we either have to evolve, commit to becoming part of the machine, or die off completely. Chichester did the best thing possible, he evolved without sacrificing his stylistic integrity.

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention Netho Diaz’s art, which will lead naysayers to sit upon their rusted thrones of outdated comic book criticism and scoff at artwork that, for all of its throwback extremity, is incredibly dynamic. Diaz brings the soul of 90s visual work back but with the clarity of modern paneling. His layouts are not just creative, but they themselves help elevate the book’s script as they flow. He also does a great job accentuating smaller character moments, something that surprised me as his art style seems to be the kind to go above and beyond in action sequences but feel stunted when the story demands it to express humanity as opposed to just violence. Diaz isn’t just a throwaway artist with nostalgic talents but a genuine one that has a level of artistry unseen at Marvel right now, save for a few highlights.

The only thing this series is missing is the absolute iconic cover art and imagery of Chichesters original run. While I love Mark Bagley as an interior artist, there’s just something so captivating abotu Scott McDaniel’s cover game from the time that this current title just isn’t matching. From the outside it wears the skin of yet another mundane nostalgic retread ala the current return to Superior Spider-Man, something Bagley is also doing covers on, that this book doesn’t quite fit the bill for.

After all that gushing, you may be wondering why this matters. Why a failed idea being rectified is so important. Well, for starters, it holds within something of substance that its launch partner, Marvel Super Heroes Secret Wars: Battleworld, doesn’t. Daredevil: Black Armor doesn’t exist solely to capitalize on an anniversary. Instead, this series is giving something forgotten its chance to shine with artistry stronger than it ever originally had. It’s a gateway into the strange parts of comic history and a chance for readers to escape a violent slog of repetitive nonsense that partially exists just to shovel off variant covers to ensure a safe bottom line.

It’s two birds with one stone, but whether or not Marvel learns the right lesson from this remains to be seen. What follows could either be a slew of cash-in mini-series, but this time with full focus on the 90s, or a continued focus on revitalizing the publisher’s darkest history with a shot of modern energy. I, for one, simply hope we get more of the latter than the former, and that Chichester gets continued chances to prove how much his abilities as a storyteller have evolved in the decades since his first crack at Daredevil.