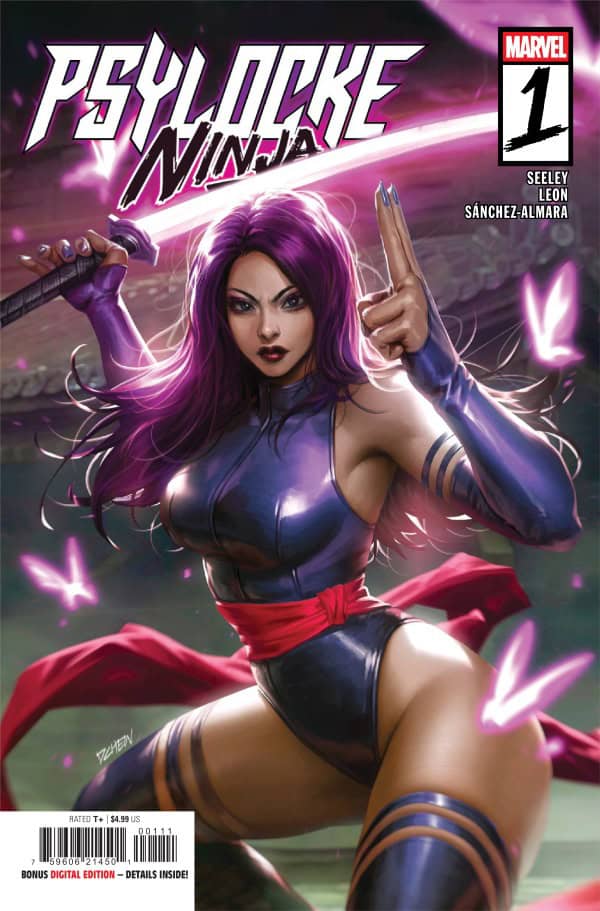

Psylocke: Ninja #1

Recap

BETSY BRADDOCK: MUTANT, X-MAN... NINJA!

Flashback to a time when Psylocke was reborn into the ultimate killing machine. What sacrifice did Betsy make to save the X-Men? Why did the Hand choose Psylocke to be their weapon? And what does it have to do with their former assassin... Elektra?! Writer Tim Seeley (ROGUE: THE SAVAGE LAND) and artist Nico Leon (MARVEL RIVALS) answer these questions in a lost story from the X-Men's past!

More X-Men coverage from Comic Watch:

Review

The X-Men’s Outback base has been raided, and the team has been scattered to the winds. With the Reavers on their heels, Betsy Braddock (Psylocke) takes what remains of the X-Men to the Siege Perilous, a multiversal gateway that will give them new lives in exchange for their memories of their present ones. With no other choice, Betsy psychically nudges her apprehensive comrades through the gateway, herself going last. She winds up in Japan with no memory of her life as Betsy Braddock or an X-Man and is taken by the deadly organization known as The Hand. Her broken psyche being implanted in the body of the assassin known as Kwannon, Betsy’s odyssey begins.

When this book was first revealed, I was eager to read it. Alyssa Wong’s recently ended Psylocke solo series focusing on Kwannon was an entertaining read so I expected more of the same if she was returning to a revamped title, but when the solicit dropped I found all of that intrigue evaporate into the night like the titular ninja. I won’t sugarcoat it, I have no idea why this book exists in 2026. I understand that this is another “flashback” series where Marvel revisits beloved characters and eras from yesteryear, but for Psylocke there was no need for a book like that to be made because of just how problematic Betsy’s time as “Ninja Psylocke” was.

For the five of you reading that are unaware of the complicated and controversial history of this character, allow me to give you a brief summary of 20+ years of publication history. Betsy started out as a blonde haired, blue eyed, white British woman. Because of comic shenanigans she then became a purple haired, cybernetic-eyed, white british woman. After going through the Siege Perilous in 1989, she became a purple-haired, normal eyed, Japanese woman but still had the brain of a very white British woman. This very confusing, as as very offensive, predicament was originally planned by then X-Men writer Chris Claremont as only lasting for a single story arc, but the surge in popularity of this new version of the character (who again was a WHITE British woman running around in a Japanese woman’s body) with readers, which was enhanced by a rookie Jim Lee’s artwork, caused editorial to make this the status quo for Betsy’s character for over 20 years. Betsy and Kwannon would not be put back to normal until 2018, not long before the linewide relaunch caused by Jonathan Hickman’s House of X of Powers of X books. During the Krakoan Age, Betsy would become Captain Britain while Kwannon would continue on as the Ninja Psylocke that fans had grown to love. It was a rare case of Marvel successfully having its cake and eating it too. So it’s baffling why they would release a story that would remind readers of that time where a white character was essentially performing yellow face.

It’s this frankly, harmful and wrongheaded decision that affects my overall enjoyment of the book. Which to be honest is nothing to really write home about, at least in this opening issue. Tim Seeley does a serviceable job of emulating the Claremont-isms, but lacks some of the nuance that made those same quirks such an enduring facet of his run. The objectification of both Betsy and Kwannon is a bit off-putting, but the fact that obvious villains are doing makes it a tiny bit more bearable.

On the artistic front, while this isn’t the strongest outing for Nico Leon, that could just be because his pencils don’t fully mesh with Dono-Sanchez Almara’s colors. All that being said, there are a couple of pages that stand out in a good way so the books is never visually boring.

Final Thoughts

Personal feelings of the overall concept of this series aside, the first issue of Psylocke: Ninja is inoffensive enough on a technical level to warrant a glance if you have nostalgia for this time in Betsy Braddock’s history. Otherwise you’re likely fine sticking to the main X-Men series if you want to see Psylocke.

Psylocke: Ninja #1: An Exercise in Frustration

- Writing - 7/107/10

- Storyline - 6/106/10

- Art - 6.5/106.5/10

- Color - 6/106/10

- Cover Art - 6/106/10

Good

Decent reading and it shows why Betsy will always be the better Psylocke. She has complexity and nuance unlike her generic impersonators.

“have no idea why this book exists in 2026”

How do you have a job in this industry?! this review is oozing with bias and sells short the reason this book does exist in 2026. There has been a sizable push to slander Betsy as a bodysnatcher and this modern retelling puts a stop to the mountains of misinformation being spread across social media. You don’t have to like this story, that’s not the point. This “review” makes it abundantly clear you do not have your finger in the pulse of the industry or fandom.

This review fundamentally misunderstands the purpose of revisiting uncomfortable or controversial eras in serialized storytelling. Art especially long-form, generational pop mythology like superhero comics is not meant to exist solely to reassure, comfort, or align with present-day moral consensus. Art is meant to interrogate, to provoke thought, and to force both creators and readers to reckon with the contradictions, failures, and harms embedded in its own history.

The argument that Psylocke: Ninja should not exist because Betsy Braddock’s time in Kwannon’s body was “problematic” is, paradoxically, an argument for erasure rather than engagement. Ignoring that era does not undo it. Pretending it never happened does not repair the harm or deepen understanding. On the contrary, refusing to revisit it risks flattening the character’s history into a sanitized version that is easier to consume but intellectually and emotionally dishonest.

Betsy’s tenure in Kwannon’s body is not merely an embarrassing footnote to be swept aside; it is a central trauma in her narrative identity. For decades, Betsy was not simply “wearing” another body, she was the site of a violent editorial and narrative decision that erased Kwannon’s agency and turned Betsy into a deeply compromised figure. That history is not something new readers should be shielded from. It is something they should be taught to understand correctly.

One of the most damaging modern fandom simplifications is the idea, repeated endlessly on social media, that Betsy is a “body thief.” That framing collapses complex, coercive, and victimizing storytelling into a meme-level moral accusation. Revisiting this era is precisely how creators can recontextualize it: to emphasize that Betsy was not a willing participant in this transformation, that she was herself violated by forces far beyond her control, and that her identity was fractured by editorial decisions she did not author.

In that sense, stories like this are not endorsements of the past, they are critical examinations of it. There is a crucial difference between depiction and approval. Historical fiction does not glorify every injustice it portrays; likewise, revisiting Ninja Psylocke does not automatically celebrate yellowface or fetishization. It can, when handled thoughtfully, expose the harm, show its consequences, and reframe the narrative so that readers understand who was hurt and why.

Moreover, the claim that Marvel had already “solved” this by separating Betsy and Kwannon and therefore should never look back is narratively shallow. Trauma does not vanish because a status quo changes. In real human psychology and in serious character writing history leaves scars. The past continues to inform identity, guilt, shame, memory, and growth. To forbid stories that engage with that past is to demand a version of storytelling that is emotionally convenient but dramatically hollow.

Finally, the review’s discomfort with revisiting this era seems rooted less in concern for victims and more in a desire for ideological cleanliness: a preference for pretending that problematic history can simply be deleted rather than examined. That impulse may feel righteous, but it is antithetical to serious art. Meaningful storytelling often requires sitting with uncomfortable truths, not discarding them.

If anything, Psylocke: Ninja has the potential to do something valuable: to reclaim a messy, harmful era and reinterpret it in a way that centers agency, victimhood, and accountability — not to glorify it, but to understand it. That is not regression. That is narrative responsibility.

Erasure is easy. Reckoning is harder. And good art chooses the harder path.

I felt exactly the same way when it was revealed that the book was a flashback from Betsy’s past as ninja Psylocke. If they wanted to do a flashback story with her, I would’ve preferred they do one from her Outback era days, something where she is herself inside and out.

I don’t feel like we need a story to clarify that she was just as much as a victim as Kwannon was either. They did a great job of explaining that in the 90s in my opinion. Those who blame Betsy for the swap either misremember what happened, misunderstood it, are regurgitating what they heard from other haters, or they just plain don’t like Betsy and will blame her no matter what, but it’s not because they did a bad job of explaining it the first time.