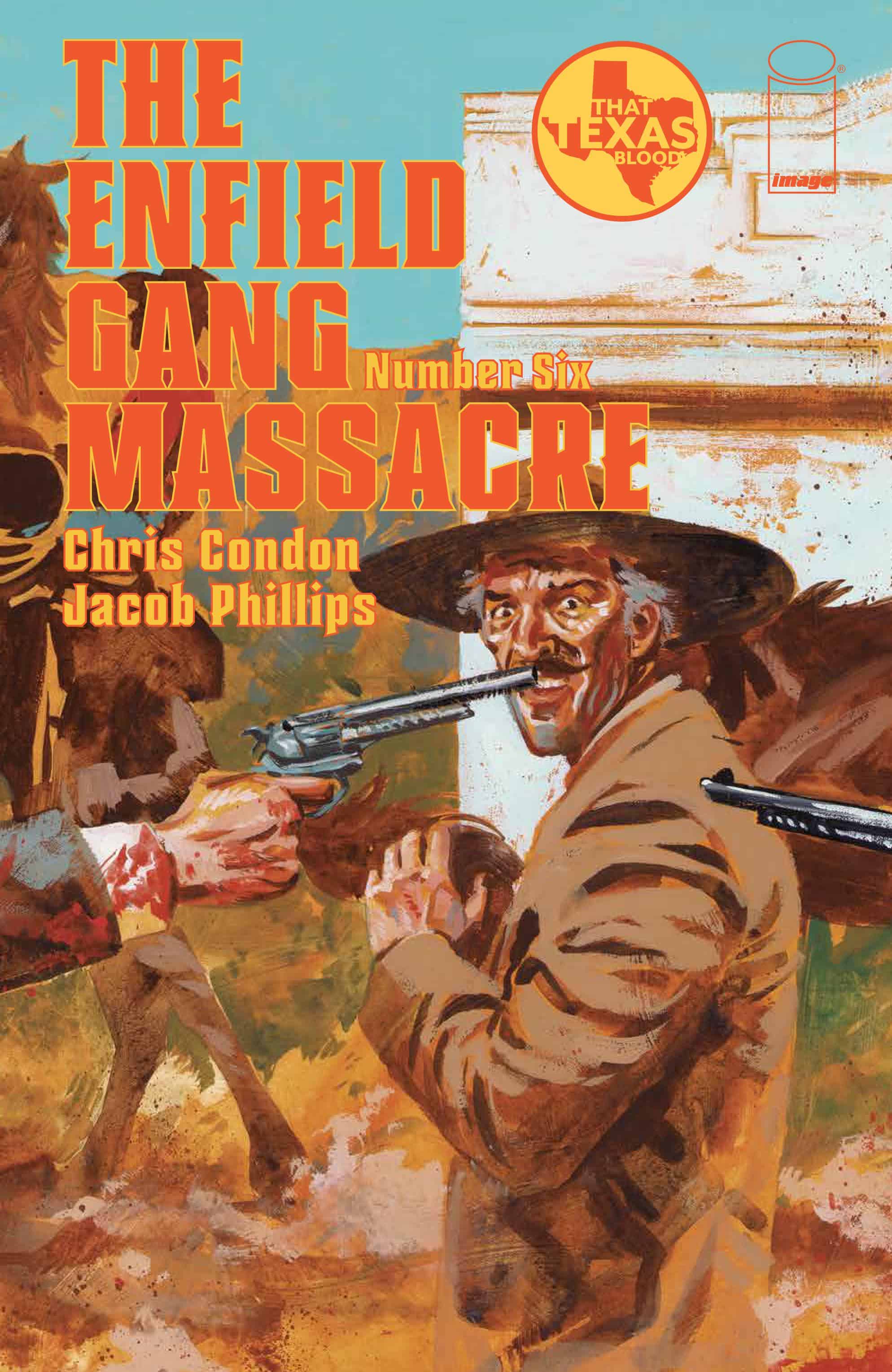

The Enfield Gang Massacre #6

Recap

Review

In college, there was a film class that was offered specifically for graduate students that reserved a select few seats for undergrads like myself at the time. With a bit of gumption and sleep deprivation, I won the race and secured a spot. All in all, it was an eye-opening experience, but there’s a single short film that has crawled its way into my mind and nestled in tight after seeing it on a Wednesday evening in the rundown media room of Moody Hall. It’s not flashy in the obvious ways, and it is discussed but never feels like a heralded choice, even though it, at one point, found its way into a Twilight Zone episode.

That film was Robert Enrico’s adaptation of An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge. The story, which follows a Civil War soldier as he is about to be hanged and then escapes, was an eye-opening experience. It presented the filmic manipulation of time, the subversion of expectations, and the art of the non-linear narrative to instill such a deep shock that I feel I have never fully returned from it. Time and time again, that feeling of a Copernican revolution in terms of craft and artistic intent has been at the forefront of the mind when reading The Enfield Gang Massacre.

The Enfield Gang Massacre #6 – written by Chris Condon with art, colors, and letters by Jacob Phillips and color assists from Pip Martin – is a heart-wrenching affair, closing out one of the poignant stories in recent memory with yet another twist of the narrative knife. The issue delivers on the promise of the premise for the series, showcasing the final act of the titular massacre. After being caught in the last issue, Enfield and Amy find themselves put on trial for the supposed crimes of issue one. The local judge comes to offer a bit of equity while delivering the reality of the situation; Enfield is to be hanged while Amy will be exiled and expected to warn others of what committing crimes earns.

Condon’s scripting for this issue is an excellent showcase of sparse writing for the bulk of the issue, showing an explicit trust put in his collaborator. Condon’s story and dialogue, like this installment in many ways, find itself in a fluid state, existing between two poles at every turn. For every sequence of sweeping, silent stolen moments, there’s an equal beat of buttery back-and-forth, thick and rich in the Texas/Western slang that Condon has captured in every page of this series and its progenitor. Like the mythic notions of the West that stand in opposition to its reality, these disparate styles of writing seamlessly blend and lock into place, feeling so stylistically in sync with one another.

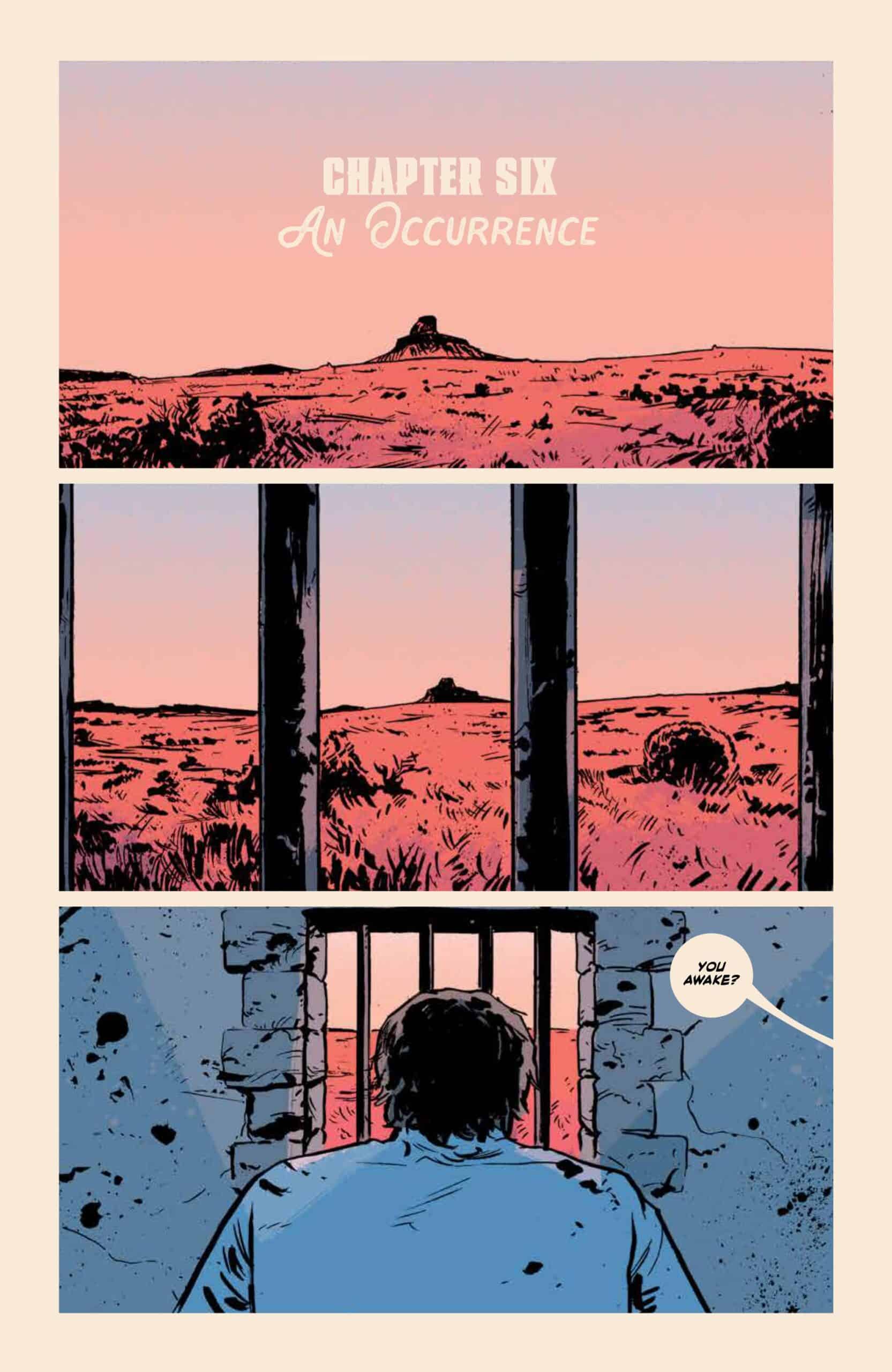

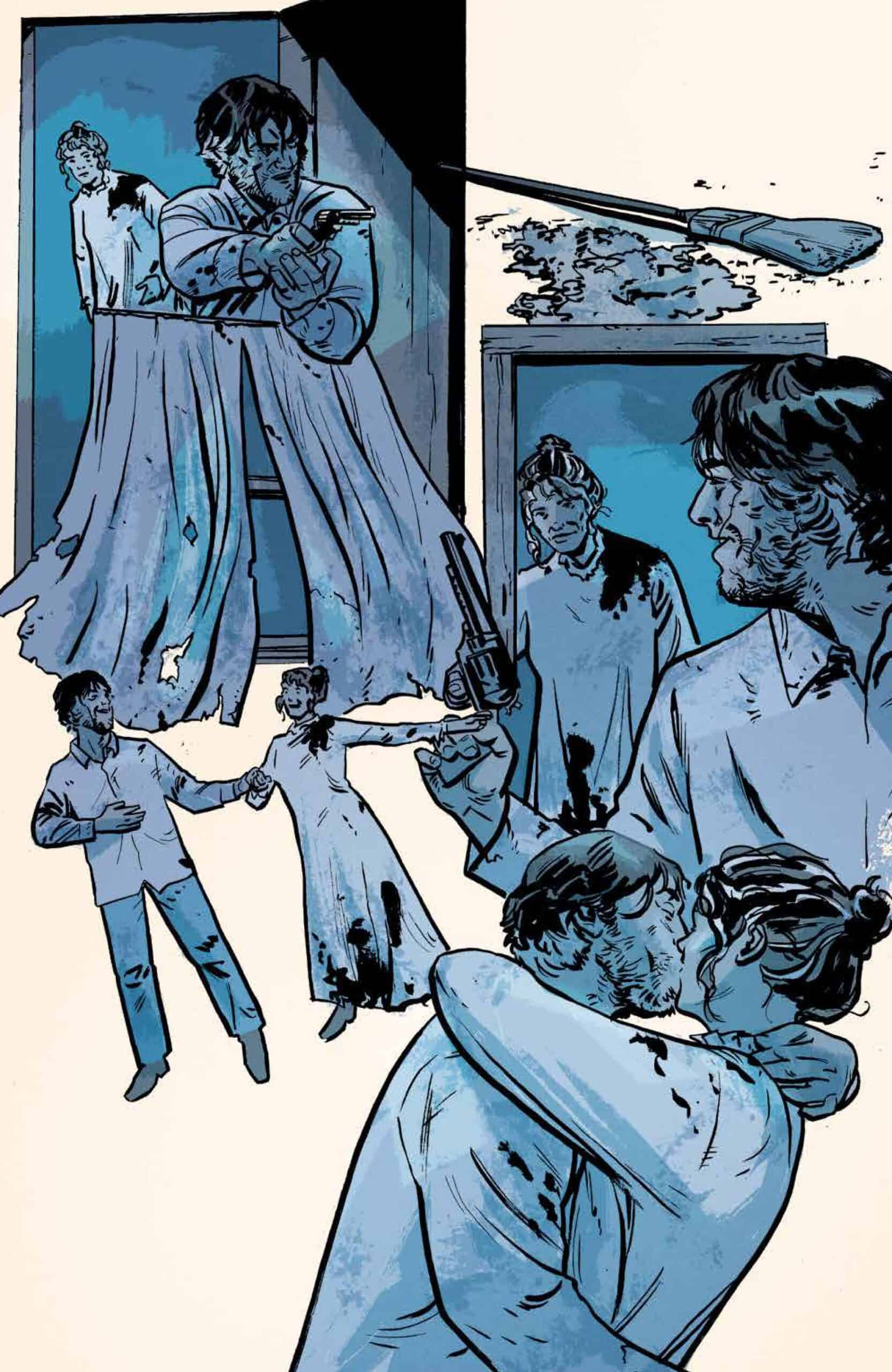

The middle sequence illustrated and colored by Phillips is the essence of the issue, enriched by the singular boon of the artist’s work in depicting such an expansive, expressive tapestry. It evokes the previous issues, especially the moments of Amy’s dreams and the doom they prophesized, trading in the very controlled, yet cinematic, paneling of the book for a series of splashes that evoke the never-ending expanse of Texas and the wider west. The shift in style makes clear a wildly different rhythm for this sequence, and Phillips can showcase the full range of his pencils without a single word balloon or caption box to cover the art. It not only speaks to Phillips’s skill as an artist but as a storyteller as well, that the silent beats can play out in such crystal clarity that it feels like words would only hamper it.

This is where we must part and tip our hats if you have not read the issue. There is such a monumental twist for the issue that resonates in the collective unconscious of Western fans that is obvious yet revelatory all at once. Read past this general review at your own peril. Spoilers stalk these parts and the safety of your reading experience cannot be guaranteed.

Even before Condon and Phillips lay their cards and reveal the core reference that lies at the heart of this issue, there are some clear hints. The break in structure is the most obvious, between the switch to the splash pages and silent scenes. The eloquence of the West has never been too far from captions, and the structured layout has been a seminal part of establishing the cinematic feeling of this series. To break from that visual language is a deliberate push from these consummate creators, venturing into paths unknown. For a brief, shining moment, there seems to be a light at the end of the tunnel. Could Condon and Phillips actually pull off a sleight of hand that undercuts the classical tragedy they’ve been riding towards? Can Enfield escape the cycle of pain and violence with the love of a good woman and the prospects of a child in the distance?

The answer is a resounding no. This is not a subversive piece in the expected ways. It is a classic story of a criminal punished for his apparent sins, even if the crime he’s hanged for is not the actual crime he committed. Enfield and Amy don’t get to grow old together, nor will Enfield get a chance to meet his child. Instead, the splash pages deliver yet another look inside Amy’s mind, this time channeling the famed An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge by Ambrose Bierce to deliver an agonizing glimpse of happiness before the world rips it away. Enfield is hanged as promised, and Amy is left to live without him, far away from Ambrose County. Even in death, Enfield gets no peace, his body left and then sold off in the future to the fair that bookended this series.

Phillips splashes for this fantasy sequence explore space in such a dreamlike quality, in which the montage of images bleed into each other. Panelless, another visual cue that something is amiss, this sequence features beats like hands hammering in a nail to the side of a fireplace, evoking the sentiment of repairing or building the heart of a home. The threat of violence with Enfield’s gun in hand, then sweeping Amy off her feet in a moment of pure, unbridled joy. From the birth of a child to the repetition of guns, this time as an activity to bond father and son split across the page using the fence line holding practice target cans. Each moment that Phillips illustrates and colors in these splashes feels like fully realized slivers of time, unfolding from themselves with the idealization of a life well lived. They’re like sweet nectar, the first taste of water after days stranded in the desert.

In a moment, they’re ripped from Amy, and in a way, from the audience in an act of dressed-up cruelty. Under the pretense of law and justice, Enfield is hanged and Amy is forced to watch, with no amount of fantasizing that can obfuscate. It’s a shattering experience that returns the book to its reality, where the ruggish outlaw with a clear head of gold is left to pay for the sins of the frontier as a whole. In the aftermath of the hanging, there’s a decision to never show Enfield’s face up close, until the framing device. That decision from both Condon and Phillips helped to sell the tragedy by placing the reactions solely on the living, while still giving Enfield the tiniest bit of respect even in death. Enfield is gone, and it’s Amy, and us the reader, that have to live on in the wake. Living through the pain and contempt the tough-as-nails frontier woman has for everyone. She utters her curses and claws for the last shreds of dignity for Enfield, and Phillips draws the hell out of the moment.

While the art and story have been an instrumental part of this series, there is no doubt it would not be what it is without Phillips and Martin’s coloring. The book has, since issue one, played in and exploded out, the tones one would expect for a Western. The harsh, faded grits of sand and beating sun have reared their heads in the colorscape, but the coloring has bucked that emphasis for something much more textured. Blues, pinks, greens, and purples have felt like the primary palette of the series, even as it has ventured into the desert and bloody red gunfights. This is a western by the way of a Terrance Malick film, rendering the natural lights of the world always in the magic of dusk and dawn. Storms brew in the distance, a cold edge inflicts the modern day, and not even Enfield and his outlaws can escape the passage of time and the setting of the sun.

Phillips and Martin get to explore both sides of the West in this issue while bringing that modern, moody lighting and hues to the return of the framing story. It’s such a departure from the rest of the book, yet still in total alignment with the atmosphere, that it shocks how easily it is to forget it’s a jump into the future and place. The coloring, just like the art and writing, dismantles what it means to be a Western, before returning to the tropes and aesthetics for a rich, authentic final delivery of tragedy.

Final Thoughts

The Enfield Gang Massacre #6 is a definitive ending to a once-in-a-lifetime miniseries. It closes out an epic mythic on the most personal of beats, compressing the heft of massive themes into the ultimate expression of tragedy; love cannot save the sinner. Condon’s scripting is the epitome of a creator trusting their partner in craft implicitly, seceding over the most important sequence of the comic without a single word on the page. Phillips takes it and runs, painting out the fantastical life of a happy couple in a flight of fantasy that hurts more than any death or moment of failure because of its impedance. Philips and Martin match that dynamic for an utterly captivating expression of the West in colors that feel antithetical yet so in harmony with the story.

Now that all of The Enfield Gang Massacre is out, those who have not picked up a single issue need to at once. Regular readers, start it again from start to finish. This is a book that will be talked about for years to come. It is a book that feels like a prologue to a whole, wider world of stories from Condon and Phillips. To see how they top this one feels a bit like living through the Incident at Owl Creek Bridge. Is it possible this is just a collective figment of the imagination? Or is it the gift of another day, another story, just waiting in the wing?

The Enfield Gang Massacre #6: ‘Debts That No Honest Man Can Pay’

- Writing - 10/1010/10

- Storyline - 10/1010/10

- Art - 10/1010/10

- Color - 10/1010/10

- Cover Art - 10/1010/10