Patricia Highsmash

Five Ways to Read Final Crisis Pt. 1:

Four Dimensions

by Travis Hedge Coke

If we read only the comics running parallel to Final Crisis, which are written also by Grant Morrison, Final Crisis is a story of Superman going outside to promise a future and Batman going inside himself to find satisfaction in what he has done, while two fathers, two hypocrites, two teachers do their best to help their community, and cruel gods condescend to them all.

“I say people will make their choice within the dichotomy presented by the mother company; they will not go outside it, because then the issue would become vague and the implications of the choice no longer clear and satisfying . . . satisfying in terms, I mean to say, of the self-orientation for which they do, in the last analysis, buy these products at all.”

– The Magic Christian, Terry Southern

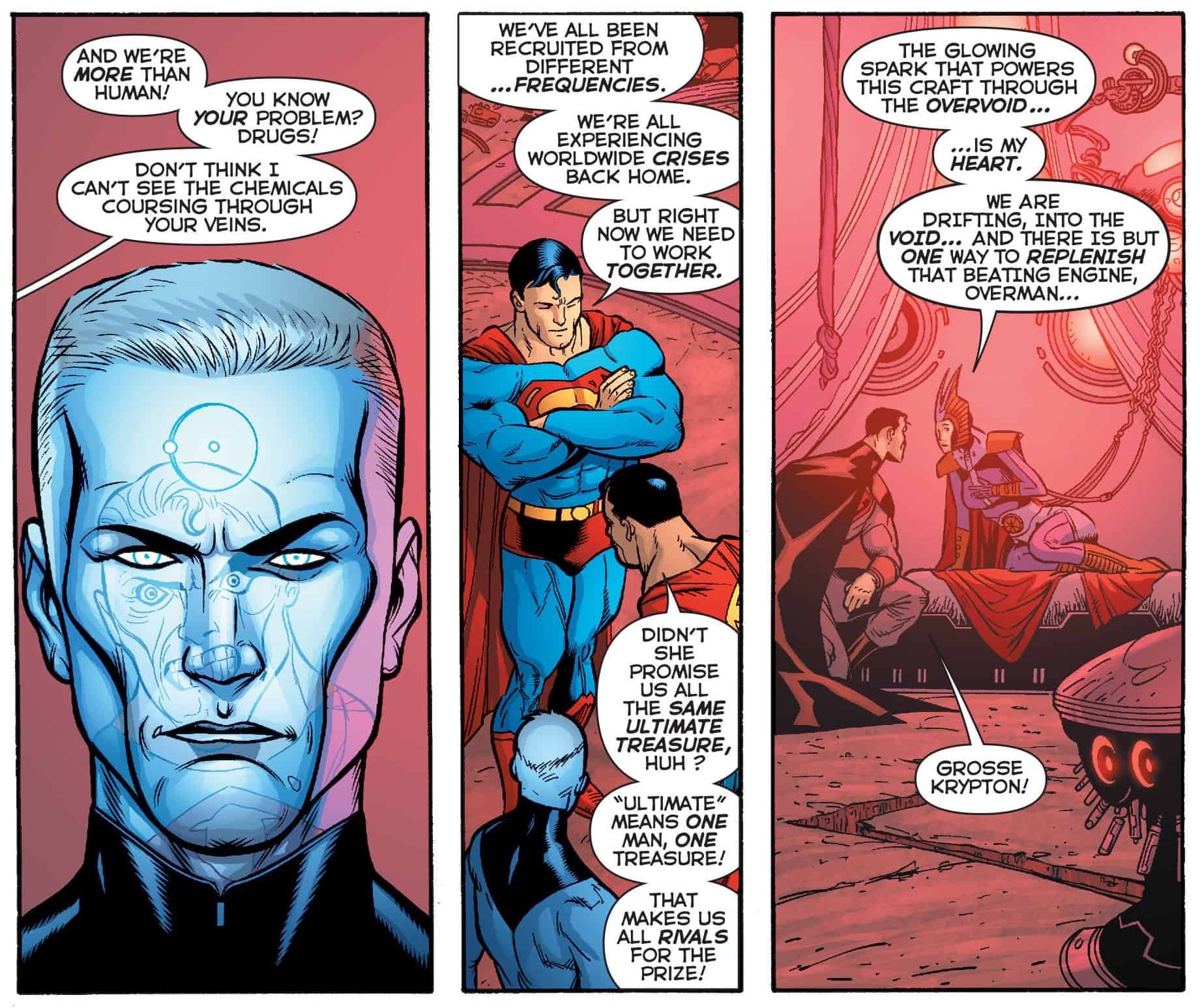

“‘Ultimate’ means one man, one treasure!”

– Ultraman in Superman Beyond, Grant Morrison, Doug Mahnke, et al

“I’ve never recovered from someone asking for advice on writing a horror movie and being told, ‘Make sure you follow the Hero’s Journey.’”

– Anecdote I can no longer source and I literally only read it yesterday.

Story has to be imperfect. Everybody loves the idea of a tight story, a tight novel, tight movie, but are those your favorite movies, your favorite comics or novels? Generally, they are not.

We like when there is something missing, when something is off. We like the idea of formalism or strict formality, but it is more fun if someone never uses the letter e in a whole book, except once. If a comic is nine panel grid, nine panel grid, nine panel grid, and then for one page, one good gag, it is not.

Before Final Crisis began, a prologue: A burning figure falling through upended panels, planes of realness, casting a “gigantic shadow” which only one person can see, a narrator with races and running on his mind.

Criminals of pretentious sorts gather as a masked preacher sells them a bill of goods he calls, “balanc[ing] the books.” A super fast man vibrates a blur, resembling the 3D special effects we will soon see in Superman Beyond.

The flaming figure grabs something, tight, making a fist.

There is lightning.

Final Crisis is a tentpole Event comic published and owned by DC Comics, which is consciously about not just Event comics, or just comics, but story as a verb, noun, adjective, adverb, and kind of a pronoun. An Event comic is typically a miniseries which both fosters a number of ancillary storylines in other miniseries, single issue comics, or a- and b-plots of ongoing titles during the duration of the Event, with widespread – thought often cosmetic – effects to the ongoing series and shared universe of a comics imprint.

An Event is a narrative and ancillary narratives, then, closer to a historic event during the time of which, many stories may be told. A particular day and locale may overlap in many Vietnam War stories or many stories may overlap regarding the Old Kindersley Corral in 1881, without being directly related or dependent on one another as stories. In many cases, as stories, the stories will need to take liberties or make choices in focus, expanding or contracting details or emphasis to empower their story.

The introduction which opens most anglophone editions of Final Crisis is, in part, the telling of the purchase and reading of an issue of Final Crisis, and in part recapitulation of scenes from Final Crisis, and maybe the purchase and reading are moment for moment accurate, but the summarization is only almost accurate. That is its power.

The events of an Event are one thing, but that thing is not the story of the events or the stories of the Event.

To embrace and comment on that, Final Crisis has its central seven parts, serialized as Final Crisis, an array of comics not written or directly overseen by Final Crisis plotter and writer, Grant Morrison, and several two-part comics – and one single-issue comic – which fit into the narrative of Final Crisis without doing so necessarily chronologically or as requisite story points. These all form a constellation of a grander Final Crisis, without overriding or diluting the principle Final Crisis story-narrative, those seven sequential issues labeled, Final Crisis.

The Morrison-written satellite comics retell, reframe, and reify Final Crisis, taking place before, after, and during Final Crisis while establishing new landscapes and timelines, from the farthest possible external of Limbo and outside space and time and the internal and intimate of one person’s deepest traumas.

While the two fathers of Submit have to deal with immediacy and direct, non-existential threats, Superman Beyond is a journey to the far reaches and far-reaching, moving beyond space, beyond time, beyond doubt, ennui, and death. The Batman of Last Rites and RIP: The Missing Chapter, rather than going anywhere, realizes, “As I stayed in place, he manipulated whole centuries around me. I was locked into a spinning cage of events.”

Without a central narrative, without the central narrative, the significance of the events of the Final Crisis miniseries is de-stigmatized.

The main miniseries, Final Crisis, has had a stigma concretized around it since before the comic even began serializing. It was complicated and impossible to understand before a single issue was published. The satellite comics, with their clearer foci, singular protagonists, and shorter page count are easier to take in all at once, but also avoid the points which are most often mythologized as too difficult or inexplicable. The bigger mysteries cease to matter (too much).

Superman Beyond

Traditionally collected between issues #3 and #4 of Final Crisis, or #3 of Final Crisis and the Submit one shot, Superman Beyond takes place during the span of the main plots of FC #3-6. Maybe. There is a disjunction, narratively, between where/when Superman Beyond ends and the thread picks back up in Final Crisis or elsewhere.

Occupying possibility, the linkage from the optimistic ending of Beyond and Final Crisis should be disjunctive. In a physical, material way, Beyond is a demonstration of how mutable space and time are in story, as Superman moves from his relatively grounded reality of Metropolis (already highly fantastic to us, but at least familiar) to, first, a multiverse of familiar and sensibly-themed realities, then to a pre-established and hauntological Limbo – where discarded concepts live still-lives of no progress – and eventually the exceptionally artificial and completely changeable haunted reality of the Monitors.

Beyond begins in media res, ends on an atemporal cliffhanger, is multiple quests at once, is a dream. Beyond is the coming future, the future after the future; like is inscribed on Superman’s headstone, “To Be Continued.”

Beyond also begins abnormal the first scene lacking context or preparation, presented in anaglyph special effects. Or, if a reader is unprepared, as a blur of misaligned colors. Or, in most collected editions, without the 3D anaglyph effect at all.

By page three (or is it two? two and three, in print, are a single wide page digitally, a spread), we are given the clues to know this story takes place during the time between two heartbeats, but we lack context to know what that means, in mechanics, or how those mechanics could be.

A few pages later, we witness the mechanics, a device created for that specific goal, by a Monitor, Zillo Valla, who simply thinks it into being because she needs a narrative excuse for the effect.

Valla needs Superman to journey with her beyond his reality, and to that end, she has suspended time so that a dying Lois Lane is in what could be her final moment of life for as long as Valla needs. A plot requirement manifests physical, experiential reality.

Already onboard her Yellow Submarine-looking vessel, the Ultima Thule, are alternate reality Supermans she had previously gathered. An evil, selfish Ultraman. A childlike wish-hero, Captain Marvel. An academic exercise, Captain Allen Adam.

Neither the name, Ultima Thule, nor the design reminiscent of the submarine from the animated Beatles feature film, are necessary to understand in full, to appreciate the story, but knowing that Yellow Submarine is about taking a special vessel through metaphoric and symbolic islands and seas, or that Thule is a hypothetical island farthest north, and Ultima Thule, an island out of possible reach, an impossible land beyond touch, makes the ship, itself, a microcosm of the miniseries’ central concepts.

The Supermans and Valla take the Ultima Thule to an alternate reality, where they encounter other alternate reality Supermans, some immediately identifiable as such, and others only clear in retrospect. A Superman who is a demon merged with a human, a Superman who is a magician in a world of faux nostalgia that smells of cotton candy, newsprint, and cigarettes.

Each Superman onboard the Ultima Thule has been promised a grail, a sacred thing, for their participation in the Monitor’s quest. Overman is promised his lost cousin (whose fate we will learn in Final Crisis proper, and whose nature as a clone of him is revealed to us in The Multiversity, some years later). For Captain Marvel, a piece of the fractured Rock of Ages which properly sits at the center of the multiverse and imagination. For Captain Adam, a return to his world.

As they skip from reality to reality like a stone across a lake, the Ultima Thule and its Supermans arrive at Limbo, a place where “nothing ever happens” and obviously things do happen. A place of holding patterns, ennui, and self-aggrandizing pity, peopled largely with forgotten superheroes and villains who, of course, are not really forgotten, only widely unused except their appearances, now, in Limbo.

Limbo’s king is as common as anyone, all pitiful and powerless together, by the name of Merryman. When the Supermans encounter Merryman in Limbo, Merryman is only slowly revealed as, himself, an alternate Superman, not by crest or spit curl hairstyle but by role, by purpose and use. Where goes Superman, goes inspiration; goes rebellion from acting against ourselves.

Limbo is supposedly so boring, so stuck, so basic, the library there has only one book, which no one can read. So, of course, Supermans, working in tandem, read it, and it is not only the only story, but the story of everything.

That story of everything released, for them, the story of Monitor, which is the same thing, and Monitor’s realm, which is, of course, the same thing. Monitor and Monitor’s really are story. “Narratives [form] are them, like crystals in a solution.” “Primal forms in a fundamental world.” Monitor is a place, a populace, a history, a future. Cityscape, ancestry, relationships form as they are imagined, as they are suspected, intuited, projected.

The Monitors/Monitor doom themselves by suspecting their own guilt and compliance, creating, of themselves, a vampire god, and then that they are a population of vampires. They save themselves by imagining Superman, someone who will protect them regardless of their “self-loathing and rage.”

Like Monitor, like Merryman in Limbo, our Superman needs to understand that there are no real opposites. As Captain Adam says, “No dualities. Only symmetries.” The different Supermans can form a constellation of a bigger, truer Superman. Two or more Supermans, together, can make up an asterism by which we understand something beyond Superman.

Superman’s reason to be is to protect and save even when everyone is against them and against their own self-interest. Mandrakk is everyone/anyone fighting against their own self-interest. “Mandrakk is the opposite of life.”

As Superman returns to his wife, to save her life as she lies frozen in time in her hospital bed, Mandrakk is reborn in another Monitor, another person-piece of Monitor, who also feels so much guilt and rage they will work totally against their self-interest, and with them, now, a flawed, evil Superman, a bad copy of Superman. A vampire Superman.

That, of course, is a story to be continued.

Last Rites

In contrast to Superman Beyond’s note of potential and hope, Last Rites pares down possibilities, most of them regrets, to something that is. It is about insistence, a very particularly self-serving, fatalistic, yet still positive insistence. Symmetries resonate into a symphony, or a cacophony, but a cacophony is also a unified thing.

A duology of butler-centered issues, Last Rites was also a brief imprint of Batman-related stories across the family of ongoing comics. Apropos for such a brand-conscious character and a brand-conscious story.

Superman Beyond begins in the material, grounded world of a city hospital before expanding out to other larger real realities. Last Rites begins in speculations inside a fantasy inside a manufactured dream inside someone’s mind.

Alfred (secretly not Alfred, but the Lump, an engineered psychic attack) tells Bruce of worse possibilities than him being Batman or being left to die. A moth or snake-themed hero; owl, cat, raven, mosquito, a skeleton guise called, The Phantom Skeleton and a stage-themed hero or The Curtain. Bruce hallucinates Alfred leaving him, his girlfriend, Julie Madison leaving him, a Robin dead without him, a Batwoman who thrills and abandons him. A life of micro sleeps and casual non-intimate physical romances. A Hamlet who in that play could don the guise of Batman to fix all his woes.

When Batman is done threatened with Batman-like avenues which could be worse, or what a shame Batman is, as a role, Alfred/the Lump hits him with a new set of visions, a fractured life without Batman or the murder of his parents. A Bruce Wayne who is an even bigger deluded chump than he sometimes pretends to be to throw people off the scent of his superheroic nature.

What if Bruce Wayne is dizzied by Catwoman, a thief, a sex worker, a common woman? What if she runs circles around him and humiliates him in front of his important colleagues and powerful neighbors?

She is. She does. And, as Batman that is kind of acceptable to him. But, Bruce Wayne? Wayne has classism he cannot examine, sexism he will not accept in himself, and an anti-sex streak wider than the white paint striped down a cat’s back in a Pepe Le Pew cartoon.

Batman’s allies as superior women who scare him excitingly, a bachelor father soldier actor medic gentleman’s gentleman, an awesomely talented and friend and enthusiastic child warrior bringing color and life. Batman is a way for Bruce Wayne to cope and also a way for Bruce Wayne to remain private, protected, and have a family. To have romances he can encounter again and again, with whom he can share something strong and secret, Bruce needs Batman, a fetish suit, a weighted comfort blanket, a high-tech version of dad’s suit he can wear to be a man.

Batdrag is the best drag. Superman wears his culture’s traditional garb. Batman wears party clothes. He wears his dad’s old fancy dress party crime-committing suit.

The regrets which come close ending Batman are not projections, not childhood anxieties brought to fore, no hypotheticals thrown at him as possibilities, but the real deaths and tortures and losses of those around him, those he feels he inspires, who he is most responsible for. The death of children he recruited or who mimicked his style, the childhood friend he had to punch out, the trauma victim he tipped over the edge by asking him to temporarily be Batman. And, every bruise, cut, broken vertebra, gouged eye, and city-swallowing earthquake received in the nightly course of being Batman.

Bruce gives all this to the Lump, all this to himself. These real traumas are what kill an entire army of clones of the Batman. Batman dies every night he goes out. Batman dies every time Bruce Wayne wakes up. Batman fights Death, and it is a kind of play fight, anymore, because Death is his friend.

As Last Rites rolls up to a conclusion we understand why Batman has been in a cruciform pose the entire story, why he is stabbed in the cowl with a crown of thorns, why his arms are outstretched so (and, in RIP: The Missing Chapter, we will understand he was in this crucifixion for three days).

Superman flies out into other worlds, bigger existence, and Batman needs to entrench himself into our material plane, our streets and wounds, to feel the temptations of our world and to suffer a suffering explicitly of us.

The first thing, in the Bible, that Jesus does after he is resurrected, is to tend a garden. Jesus goes to work. Batman, a job who is also a man, goes directly from the many deaths of his clones to the work of stopping a murderous, cruel god, as we will see in RIP: The Missing Chapter.

Submit

All of these satellite comics are male-oriented, male stories, and all of them accomplish this by also putting the men in what are frequently feminine roles as well as the masculine. The only one to put a woman in any typically masculine roles is Superman Beyond, and there, they are an emanation of a masculine-identified source-being and Lois Lane, the Dreamer of Reality, who was created as a foil to a man.

Submit moves its women to either very tertiary roles – as wife/mother and daughter – or quinary, entirely off-scene roles, with Black Lightning’s daughters who feature only in dialogue and then, only in conversation which is less than truthful.

This reading of Final Crisis becomes male dominant and makes masculinity the universal or base. Superman can beget a Supergirl, a Lois Lane, and Batman can produce a Batgirl, Batwoman, an Elva Barr, a dead mother, but they have to come from an a priori man.

Black Lighting vs the Tattooed Man. Nerve versus skin. Brain versus Touch. Internal. External. Vocation vs Job. Standards vs Priorities.

Man seeing Man seeing Man in Man seeing Man seeing Man in Man.

Superman can be part of a thought-robot, a plot-armor to affect change in story, and Batman is a good story that Bruce Wayne made up. The Tattooed Man and Black Lightning are superhuman, but they are subject to hunger, to cold, to a rock in their shoe, in ways that the storied Batman and Superman are not. Lighting pretends he is not, and the Tattooed Man pretends he is, too much.

Morrison says of Superman, “He’ll never let you down” – which I think is only true in an optimistic, platonic-Superman sense, because ooooh boy do we have some Superman who has let me down before – but Lighting and Tattooed Man are built to let you down a little, and for you and them to step up anyway. Different lures to the same ultimate ends.

The Thule of life is being good, the Ultima Thule, is being good all the time.

Black Lightning and the Tattooed Man are hypocrites, but people are. We cannot condemn them for hypocrisy, or ought not. We need to recognize our own hypocrisies and that they are not outside our story any more than they are outside Black Lightning’s. Building a Batman to be better is all and good, but being a good Tattooed Man is lofty goals.

When Black Lightning finds his symmetrical double, the Tattooed Man has been protecting his family by isolating them from society enraptured in a fascist collapse, hiding in a school in Washington, DC, raiding a nearby mall for supplies, burning library books and newspapers for heat as Lightning charges through the city delivering newspapers and avoiding terrible monster dogs.

It is the Tattooed Man who saves Black Lightning. For all his talk of, “if it was up to me, we’d kill and eat the bastard,” he rescues Lightning and takes him to safety, jeopardizing his and his family’s for the sake of a stranger who, because of their choice of vocation, he dislikes.

Tattooed Man sacrifices creature comforts for the frustration of doing the right thing. He is rewarded by Lightning critiquing his choices, critiquing his life and family dynamics, and his willingness to sacrifice mass-produced, outdated books (specifically, Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species) for his family’s survival.

Lightning obscures his own life and family, talking of his superhero daughters as if they really like him, as if he approves – to their faces – of their choice to be superheroes. Lightning’s own nuclear family dissolved in divorce and he is, while a good man, notoriously judgmental, tough-talking, and acts morally superior.

Lightning and the Tattooed Man are too alike. We may not have two wolves inside us, as the famous televangelist parable teaches, but we may have two people inside us, who are much more alike than either wants to admit.

Together, Lightning, Tattooed Man, and family escape via school bus, pursued by brainwashed fascist soldier-drones who used to be everyone on Earth.

Lightning offers to stay behind and ward off attacks long enough for them to escape, but he is conquered, possessed, turned evil, too.

The Tattooed Man gets his family free, but he stays, now accepting himself as the superhero he has been this entire life.

One man dealt with his hypocrisies, and ends the tale a superhero. The other, also a superhero, lied in his teeth to inspire others and maintain and image, and by the end, he is burning books for sheer malice and pathetic attempts to look hard.

RIP: The Missing Chapter

This version of Final Crisis could end there. A palpable hit so tragic it cannot even be called bittersweet. Superman Beyond tells us that “the Final Crisis” is “this last-ditch effort to save creation itself from a loathing and greed beyond measure.” But…

The Missing Chapter is a sequel to Batman: RIP, also written by Grant Morrison and drawn by this story’s penciler, Tony Daniels, and it retells portions of the main Final Crisis comic, from Batman’s point of view, but it retells them in the form of his telling of the story. Portions of both RIP and Final Crisis are altered in his telling. Batman, in his own words, is wordier, pithier, and perhaps more capable and self-aware than he was in versions we have seen, of the same scenes, from a more external perspective.

The Missing Chapter begins as hastily written journal entries for family/posterity and transitions to a recorded letter to Superman, a request for assistance and for acknowledgment. Batman, as he writes and dictates these is aware he is developing, as a tool, a story. He is not enhancing his image purely out of ego, not shaping the story to promote himself, but to promote a new and superior myth, an educative and evocative story which, itself, can do good.

The Missing Chapter is Bruce Wayne making sure Batman, if this is the end of Batman, goes out a better, healthier narrative than the narratives of evil, of cruelty, failure, jealousy, or the narratives of vengeance, suffering, and war.

A speculation with Final Crisis was that superheroes would embody specific trademarked New Gods, with Batman as Orion. In The Missing Chapter, he investigates the murder of Orion, and the two issues are filled with Orion-related motifs, star maps, callbacks, but this is different than a character possessing the body of a character.

Batman is not Orion-in-Batman. Bruce Wayne is consciously, if instinctively, creating a better (story of) Orion than either the classical Orion of literature and myth or the Orion of the New Gods, a DC Comics-owned patron god of dogged soldiers who comes from outer space.

As Batman picks himself up from the humbling disaster and temptation in the garden of a devil’s trials, Dr Simon Hurt’s attempt to convert Batman to evil, and to weaken him to worse ends, he accepts Superman’s request he investigate the murder of a god named Orion.

Orion, the DC Universe New God, is a soldier god, a god of perpetual and perpetuating war, the sacrificial pawn, the death-drive combatant. Created by Jack Kirby, in his original stories, Orion is so committed to perpetual war and his role as traumatized, exhausted soldier, he dies (and his born again; different). Since then, he has varied from different to worse.

Here, murdered, he is gone as the classical Orion, a god who came not out of religion, first, but story. The Orion of classical Greek stories is a hunter god who, in the first tales of his existence, is already dead, dead because he could not pause long enough for reflection, because he could not see past his immediate goals as a hunter. The Orion of these stories is still hunting in the afterlife. Not just a dead god or a hunter god, but a hunter in the afterlife hunting the same prey again and again.

One of Grant Morrison’s earliest times writing Batman, they had Batman declare – though purely as bravado – that they were the king of Hell.

As Superman Beyond begins inexplicably blurred and visually offset before we understand this is anaglyph special effects/requires the 4D vision powers of Superman, The Missing Chapter takes a dissolute image and tightens the focus into the kind of deductive clarity and sharpness of narrational voice of Batman.

Seiter, DanielItalie, Musée du Louvre, Département des Peintures, RF 1997 30 – https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010066903 – https://collections.louvre.fr/CGU

The alternate forms of Batman from Last Rites – the moth character, the snake, the actor, the fool – are bluffs. In The Missing Chapter, the symmetries are implicit Orions. The too-focused Orions who are dead. The hunter in the underworld. The soldier who cannot quit. Bruce has to make, and concretize, a Batman who is a better story than either.

Batman escapes the trap made of doubts and traumas which the evil god, Darkseid, and his cronies, have developed for him, as we saw in Last Rites. Knowing that the bullet he took from the scene of Orion’s murder, is the bullet, all bullets concretized into one object-idea bullet, Batman takes the first gun he can, and formulates a plan.

“The monster and the man standing in his way.”

Batman knows his time has come. He sees visions of multiverses funeral, from another Last Rites story, Whatever Happened to the Caped Crusader. He sees his own burial and pallbearers. The well on his ancestral grounds which opens into the vast subterranean Batcave. Hears “bells and thunder. The sound of ancient, rusty locks unlatching.”

Killing Darkseid would put Batman too close to those other, dead, outdated Orions. Batman can be soldier-like, but must not be a soldier. Batman can pursue, doggedly, but he cannot truly be a hunter. Batman does not kill. Batman does not murder.

To save the universe, to save reality, though, Batman can shoot once to wound a god, to humble a god. Bruce Wayne, child of a doctor and philanthropist, billionaire orphan raised by a village, son of three parents, creates a better story, a better Orion. Batman can wound a god to save a man and to offer the god a chance.

Batman shoots Darkseid in the soldier with a bullet that can, over time, kill him. But, Darkseid is already dead. Darkseid committed suicide when he fired the bullet into his son, Orion.

Darkseid sends Batman into the past, throughout time, pursued by a sick perversion of his own tale, a devil who will dog him, hunt him forever, through death and death and death and time.

What Batman shooting Darkseid does, is to give Darkseid an excuse to back away from his plans, to back away from his death, and do something new. Darkseid refuses. But, Darkseid refuses. Batman ensured he had the choice.

In his last moments of awareness, memory fleeting, trapped by time and life, Batman calls out to Superman. Batman’s role is to get in the way. Superman will protect. Batman will irritate and take a bullet for everyone. Superman will save and bullets bounce off.