Patricia Highsmash

Five Ways to Read Final Crisis V:

Asterisms and Constellations

by Travis Hedge Coke

“‘I know a very creepy Midsummer magic,’ whispered the Snork Maiden. ‘But it’s unspeakably horrible.’

‘I dare anything tonight,’ said the Fillyjonk with a reckless tinkle.”

– Moominsummer Madness, Tove Jansson

“‘I can’t study any more,’ Pippi said. ‘I’ve got to get up to the crow’s nest.’”

– The New Adventures of Pippi Longstocking, Astrid Lindgren

“Are we more or less caught up? All right. Back to the action!”

– Batgirls: Bad Reputation, Becky Cloonan, Michael W Conrad, Robby Rodriguez, et al

In 1985, as the famous Crisis on Infinite Earths got started, which is frequently pointed to as the “original” Crisis, DC Comics published the last of their traditional annual Crisis stories, a two-parter serialized between Infinity Inc and Justice League of America. The second chapter of that story is entitled, The Final Crisis.

Like Final Crisis, published twenty-three years later, The Final Crisis plays with narrative traditions, ending the story on a stark and to-be-continued note, giving us little in the way of an anchor for new or unfamiliar audiences.

Many of DC’s Crisis stories, over the decades, have played fast and loose with narratological elements, storytelling and comics traditions, and beg a considerable degree of audience permissiveness. The first of these Crisis stories, The Flash of Two Worlds, asks a 1961 audience, primarily of children, to accept both that the fictional and real people can contact one another and that there are levels of realness and fictionality. In that story, our home-universe Flash is a superhero inspired by the comic book exploits of another fictional Flash, who DC published before this Flash, and as the story progresses, he learns that Flash is also flesh and blood real, visits his world, and they team up to defeat supervillains.

From thereon out, the existence of alternate realities and the relative ease with which people can visit another of them, became a central backbone to what distinguished the DC Universe from other comics publishers’ shared universes.

The Final Crisis appears to end on a grandson killing his grandfather, only to clarify there is no death in another Justice League of America issue, itself off-beat. Writer Gerry Conway and his collaborating artists and other writers, show a faith in The Final Crisis, in an audience’s willingness to embrace a little uncertainty and to keep reading.

Two of the thoughts between Crisis on Infinite Earths, which ended a long run of annual or more-than-annual Crisis stories, most of which ran for two normative-length issues of monthly serial books (primarily Justice League of America), were that a multiverse made things unfriendly to new readers, and that a multiverse watered down specific characters or brands. Anecdotally, though, every Flash fan I know loves that there is a Flash family. Every Green Lantern fan I truck with is glad there is a Green Lantern Corps and Alan Scott knows them and has his kids. Batman fans may get fussy when Bruce Wayne goes to an alternate dimension, be it Earth Where We Are Evil or the Phantom Zone or Hell, but hell with them? Kids never seem to mind.

What a DC Comics’ Crisis is, is not precise or clear, and about as I know it when I see it as pornography in the eye of a bookstore browser. At the most liberal set of qualifiers, no one has written more Crises than Grant Morrison, except for Gardner Fox, who started the entire tradition, writing the initial Flash stories and the earliest Justice League Crises.

A Crisis was definitely not started as an exercise in making the playing field smaller 0r making sure no one’s imagination is too fired up. Marv Wolfman and George Perez may have done that a bit too much in Crisis on Infinite Earths, but even they have undone that damage in later Crisis stories, and CoIE itself remains a wellspring of confusion and a fecund soil for speculation.

There is no definite list of qualifiers with which you can check off a certain number and call a comic a Crisis. At the most basic, a Crisis involves the meeting or merging of two or more worlds, but those worlds can be alternate realities, different generations, even ethical or political worlds. Many of them involve the skies appearing red, and some are called, by fans and in-universe, “a red skies Crisis.” By the end of a Crisis story, a world may likely be changed in a fundamental fashion.

Classical Crises have involved the discovery that fiction comics tell true stories of alternate realities, that whole universes have been put to sleep, and that there exist morally-opposite universes, that ethics are a kind of cosmogonic physics. Contemporary Crises have detailed a war between two colors (Crisis Times Five), the reality-shattering frustration of the embittered old fan (Infinite Crisis), and the mild alteration of a letters page (Crisis of a Letters Page). Some Crises are huge, multi-character, ensemble cosmic-threat stories (Zero Hour: A Crisis in Time) and some are relatively intimate or occur in a smaller range (Identity Crisis).

Final Crisis brings in a set of special techniques, beginning with the infamous, “channel-zapping,” which upsets some audiences simply as a technique.

Channel-zapping was a way to enhance the disjointed nature of space-time and causality breaking down in a cosmic nightmare, by treating scene transitions as akin to changing stations on a television to the middle of other scenes or programs.

With the addition of the two-part Superman Beyond and the two-part Batman story, Last Rites, the story being told suddenly has expansions and contractions of reading phase space comparable to in-world time. A second in-world is an entire two-issue adventure of Superman, which is also a single-second dream had by an unconscious Lois Lane. A chronology of Last Rites is impossible to lock down, and could encompass lifetimes or merely days, but plays out, in the waking world, as specifically three days’ time.

Narrative Pointillism – the creation of a narrative via vignette, moment, implication, akin to the points in a pointillist painting – is used to hold the concept of Final Crisis together, the multiple narratives and experiences.

So, let us slow this down.

What makes a Crisis a Crisis?

* Multiple Worlds

* Team Up Between Worlds

* Reality Must Be Altered

* Must Pose a Metaphysical or Existential Question

* Red Skies

* Facilitates a Mapping of the DC Universe

* Expands and Celebrates the DC Universe

Multiple Worlds

A Crisis requires the existence of multiple worlds, traditionally alternate realities, but also generational, ethnic, or political spheres. These worlds have included Earths housing DC Comics’ older superheroes and their successive generations, worlds where the ethical constants of the universe are reversed, antimatter universes, funny animal universes, the shared universes of the Milestone, Fawcett, Charlton, and Marvel Comics publishers, and imprints such as WildStorm and Young Animal. Generational and political worlds have been the focus (Decisions, A Crisis of Confidence), and interaction between fictive worlds and our real world has been a theme, from Where on Earth Am I?, when writer Cary Bates entered the DC multiverse to become a supervillain, to Crisis of a Letters Page and Seven Soldiers of Victory.

Team Up Between Worlds

Perhaps the most fundamental part of a Crisis, is that it requires collaboration. People from the different worlds/spheres, have to come together, to accomplish something beyond them as individuals or within their own cosmological ranges. Two generations must unite. Two political spheres must collaborate. Two colors must blend together to make another color.

Reality Must Be Altered

Almost immediately in every Crisis story, some fundamental part of either a global or personal reality is altered on a basic level. The person/population learn alternate realities are real, or they learn of a specific alternate reality, an alien world, a secret origin to their own world, the affect an alternate reality or alternative mindset has on them, whatever it may be.

In some Crises, landmasses or physical bodies are altered, while in others, time and chronology may change. In a Crisis such as Identity Crisis, the change is one of social awareness and political savvy, as characters are forced to reckon with levels of duplicity and social ramification they had previously avoided.

Must Pose a Metaphysical or Existential Question

Every Crisis comes down to, Well then what the hell are we?, however it phrases or parses it. It is not only that reality or geography or a timeline is different, something in us and our understanding of us, ought to change. The Flash of Two Worlds allows our Flash to meet his childhood fictional hero and no one can ever take that away. A Family Crisis, coming directly before Crisis on Infinite Earths will take away the multiverse, asks directly if a multiverse is too confusing, if generations of superheroes and alternate worlds is overwhelming to new or casual readers. A Family Crisis is not about that, it just does it.

Red Skies

Since Crisis on Infinite Earths, the red sky has been a portent of cosmic doom in DC Comics. A late addition to the Crisis, it is incredibly prevalent, but less required than any of the others.

The most cosmetic, it remains a clear visual indicator.

Facilitates a Mapping of the DC Universe

DC has used many a Crisis to clarify their world, to commit some resets, trim the tree. Crisis on Infinite Earths removed canonical alternate Earths for nearly ten years of comics. The Flash of Two Worlds established alternate Earths and their existence in worlds as fictions or dreams. The Search for Zatanna and Zero Hour made walking tours of magical realms and potential histories.

Expands and Celebrates the DC Universe

By mapping, even if avenues are being curtailed, a Crisis shows off the avenues. A Crisis often allows for more interaction between differing spheres in the DC multiverse than is normal. Len Wein has acknowledged the first Crisis he wrote upping the expectations for how much interactions, how much mythos and revelation should play a role in a Crisis, but they were always the big team up, the big glut of characters and huge events a reader could wait for, annual or more than annually.

This means that Final Crisis is an overlapping of multiple Crises, with the Crisis in Rage of the Red Lanterns being a crisis of conscience, more akin to 2004’s Identity Crisis, Crisis of Conscience (2005), or Crisis of Confidence (2009), the Crisis of the strong arms of God, detailed in Revelations, a cosmological and lesbian riff on Crisis Between Earth-One and Earth-Two! (1966) and Crisis Times Five! (1999), and the Crisis of the Monitor/s in Final Crisis and Superman Beyond, an existential and fundamental crisis echoing the ontological collapses of Morrison/Case Doom Patrol and the jokes wherein God proves they don’t exist and go poof a priori.

The varying and various Crises make up that Monitor Crisis, because Monitor Crisis is the crisis of being overwhelmed.

Darkseid, Anti-Monitor, Mandrakk, are post-cosmic suicide ideations in an immortal existence. Existence cannot poof out after a cheap gag of logic. It still already existed. But, anxiety, panic, suicidal thoughts are not required to be rational or considered. By definition, they are largely not. Depression has to trade on irrationality.

So, let us slow this down.

How is Final Crisis a Crisis?

Multiple Worlds

Final Crisis involves a variety of alternate Earths, one where Nazis conquered the United States, one on which all life was ended, an Earth where Captain Marvel is the biggest superhero.

FC also features a variety of realms which are not alternate-Earths, but also not our dimension. The Bleed, the insides of the arteries of existence. The Silver City, the shining capitol of Heaven. Limbo. Monitor Realm, which ultimately is Monitor.

Further, there are disparate social strata who come together in different ways, as a ground-level, human criminal investigation overlaps with a cosmic frame job, supervillain vengeance, two divine entities having religious crises, global satanist cults, political fixers, espionage agencies, and a kid who works for a fast food franchise in Metropolis.

Team Up Between Worlds

Renee Montoya’s move from police to superhero to world cop to de facto Superman collecting an ark of alternate Earth Supermans is a through line to Final Crisis, illustrating worlds coming together in united purpose.

When Mandrakk, the basic idea of predation, makes his final attack after the end of the world, he is defeated by talking cartoon animal people, angels from Heaven, a cadre of Green Lanterns, an army of Supermans, some nerdy kids, and a Monitor exiled to Earth to work a minimum wage job and keep a one bedroom apartment, The Judge of All Evil.

Reality Must Be Altered

Over the course of Final Crisis, the physical geography of Earth is changed, the Milestone comics’ properties, including cities like Dakota, are merged in on a physical level. Time is stretched, smooshed together, manipulated, to establish an incongruous timeline.

With the end of the story, the entire population of Earth knows about alternate realities, and many have direct engagement with at least one.

Final Crisis also recontextualizes the DC multiverse as specifically overlapping stories, overlapping narrative constructions, or what are called, in-story, self-assembling hypernarrative.

Elements which bother many about FC, including the Mandrakk and Monitor storyline being so distinct from the New Gods/Darkseid storyline, or the sudden diminishing of the Super Young Team and Sonny Sumo as the arc completes, become intensely relevant with that hypernarratives aspect in mind. They are distinct storyines. Distinct stories chronologically or physically overlap.

Must Pose a Metaphysical or Existential Question

What are we, if we are stories? If we are many, many stories?

What debt, what responsibility do stories and characters have? Do authors, artists, editors hold?

How much evil can we forgive? Move past? Make recompense for? If truth is relative to the telling, what value, truth?

Red Skies

FC probably centers the red skies more than any other Crisis, as narratively significant and not only weather. Specifically tied, now, to the Bleed – a preexisting DC concept, the red-tinged liquid imagination betwixt worlds and also the physical and metaphoric bleed at the edge of each comics’ page, the white between and bordering panels of a comic, the Bleed is also, in FC, specifically, addresses as menstrual. The red skies are part of the monthly issuance of a comics’ multiverse, a particularly heavy flow, the stains on the bedclothes of Mother Holle, hanging her laundry over our skies. The feather stuffing always comes a little out when you beat the wash.

Facilitates a Mapping of the DC Universe

Clarifying an Earth as a Jack Kirby preserve, FC also detailed a variety of other alternate Earths, re-explaining Limbo, and generating a clear history for superheroism in Japan. Previous Crises, such as Crisis Times 3 and The Kingdom were retroactively given new interpretations, new implications. The realm in which the Crime Syndicate are imprisoned in Crisis Times 3 was, at the time of publication, simply a limbo, maybe a metaphor for being off-the-map, or out of casual usage in comics. A liminal space, this space is, under the light of Final Crisis, the Bleed and Limbo.

How can it be the Bleed and Limbo? These are imaginal spaces. Everything, really, that we know, is soaked in the Bleed, or imagination, while Limbo is liminality with short memory.

We begin to understand the DC multiverse as blank page and markings. Potential and actuation and actuation which can be erased, altered, overwritten, underwritten. That things will and can be made up.

Expands and Celebrates the DC Universe

The potential which Final Crisis leaves the DC multiverse and us is easy to underestimate. Some were disappointed in how quickly the main universe and its stories seemed to get back to normal, others with how little the Crisis affected storylines in individual books, despite removing Bruce Wayne for over a year and generating multiple followup miniseries. That the Super Young Team recede from significance even before the FC miniseries completed, or that Renee Montoya as a world police and de facto top class superhero lasted only for Final Crisis, these imbalances and arcs running contrary to expectation rankled noses.

How can Monitor and Anti-Monitor be so dramatically repurposed only to end their world entirely?

Monitor never wholly made sense, especially his appearances across many comics before Crisis on Infinite Earths began serializing, or even his actions in the earliest issues of that miniseries. Monitor selling weapons like a common arms dealer. Monitor engaging in interpersonal dramas to no apparent end.

Final Crisis shows us that Monitor and Anti-Monitor are parts of one being, as are all the Monitor population we had seen before in Countdown and in FC. Monitor is a lifeform bigger than the multiverse, a lifeforms which contains Heaven, Hell, Hades, Limbo, the realms of Dream and Nightmare, and a lifeforms with an extreme anxiety, for whom supposition becomes truth and truth is utterly malleable to imagination.

The Crisis at the heart of the overlapping Crises of Final Crisis, is the final Crisis of the Monitors. Monitor becomes cities, ruins, populations, bad doubles, good lovers, patriarchs, judges, and superheroes as soon as Monitor feels they are needed, likely, or appealing.

Monitor has been treated, in reflection of these revelations, as comic book editors, comic book writers or artists, as fans, readers, collectors. All fair. But, more fair, Monitor is us. Regardless of our role in comics or interest in comics. Monitor is how we live, how we worry, how we subsist.

The final Crisis of the Monitors cannot end even with an end. Of course, you wake up tomorrow. You would not notice if you did not.

So, what are Narrative Pointillism, Channel-Zapping, and Genre Codification, again? These fancy techniques by which we are taught that we are a narrativizing animal who gets a little too close to our own worries, hungers, and loves?

Genre Codification

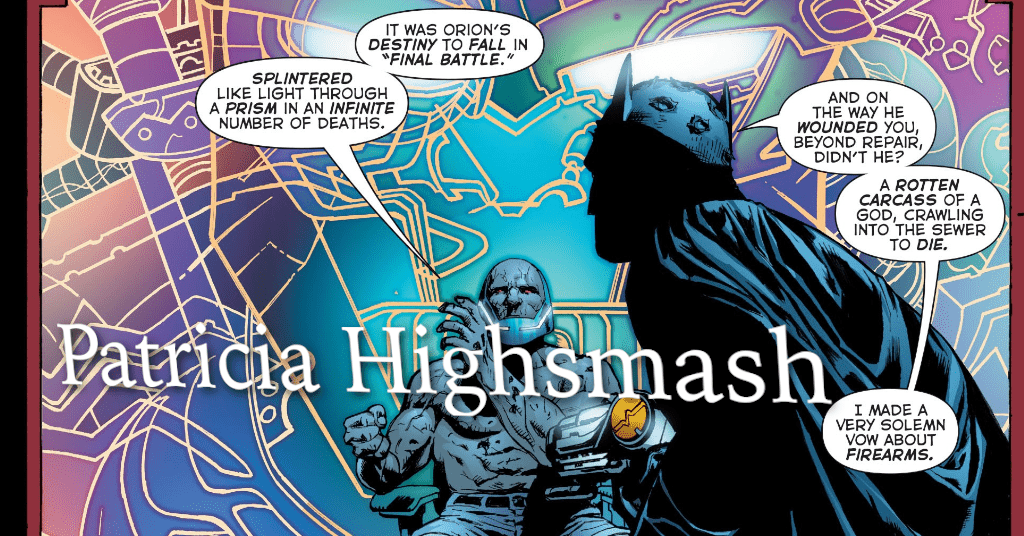

Final Crisis uses the earmarks of television police procedurals to present the investigations of the murder of Orion, the framing of Hal Jordan, and the case of several missing children. The way scenes are begun or ended, the patter of the dialogue, the angles and tone are tv crime show. We can almost hear the Dick Wolf cash register, a short piece of dun dun music used as punctuation in Law & Order programs.

When the story gets especially superheroic, even the superheroes can hear an uplifting song, and most readers who need to plug in a song for their own stability, seem to have chosen the theme to the 1978 Superman motion picture.

Every genre and subgenre has its language, keys of visualization, description, pacing, and emphasis. As Final Crisis builds a hypernarrative of crime story overlapping with superhero Event, romance intersecting with horror, those keys are highlighted and hit upon, hung like the hooks holding up a hammock, the bolts keeping a boat watertight. The steps up a complex stairwell.

Narrative Pointillism

A description of occurrence which can be deployed as a technique, narrative pointillism is the use of overlapping ensemble perspectives to create something which is not quite moment, not quite story, and not regulated by strict act structures. Robert Altman’s more rambling ensembles, Tyler Taormina’s Ham on Rye, the holiday movies which capped the career of Garry Marshall (Valentine’s Day, New Year’s Eve, Mother’s Day), initially with Katherine Fugate, are all good examples of narrative pointillism in practice.

A traditional Event in comics may have the marks of narrative pointillism, but they tend to try to create a central through line, a focal perspective, with what is called “the main mini.” I tend to find the main miniseries of an Event pretty missable. Convergence is a remarkable lot of fun, while the main mini is, for me, so-so. It is just there. I care little for the main mini of Marvel Comics’ Civil War, but the asterism of narratives following this embittered journalist or this frightened kid, across and through the tableau of Civil War, that is good. That has, for me, resonance that keeps on resonating.

Final Crisis uses its main mini to reinforce the pointillism. Stories refract, split apart, overlap like wavelets on running water, rivers in the ocean, streaks of gold shooting through granite and dirt.

During the space and time frame of Final Crisis, one perspective or narrative is not privileged, and perspective and story remain giving, opaque, intimate and distanced as they crisscross or break apart. Elements from Superman Beyond and Revelations have to crash in, unannounced, lives have to be lived without precedent or careful crafting towards a pithy point.

Channel-Zapping

Channel-zapping is kind of a misnomer, but once a name is the name, it is the name.

Channel-zapping replicates some of the feeling of changing channels mid-scene, channel after channel, in quick succession. Synchronicities appear, disjunctions occur, scenes are understood via the prologue that is now missing, the lacuna in our apprehension.

But, channel-zapping also presents multiple channels of information, of narrative, at one time, on one page.

In Final Crisis, channel-zapping helps demonstrate a shift from old world narrativizing traditions to an information age capacity for multi-channel storytelling, along with narrative pointillism and genre codification, testing waters on how much information we can embrace on the go.