Patricia Highsmash

Us Living in Fictional Cosmogonies

Part XXI: Neon Genesis Evangelion

by Travis Hedge Coke

There is an immeasurable intensity and breadth of analysis that will go into a fan’s understanding of Neon Genesis Evangelion, and that usually results in (temporary or permanent) burnout when they realize much is broadly sketched, labeled for coolness, or simply built specifically around Ikari Shinji and his narrative.

Evangelion never shies from being a constructed world and that Shinji’s internal narrative, his life and situation narrative, is as constructed as anyone’s is. More, maybe, because he is the fiction not only of his parents and his friends and himself, but the protagonist of a franchise and the audience proxy.

Every time we come too close to facing that artifice, an artificiality which Shinji has to face and contend with routinely over the original television series, various films, comics, roleplaying games, video games, et cetera – you may be saying, “Video games?” but what is the mortal confrontation of irreality and the real if not strip games played by others in which you only strip and have no agenda? – every time Shinji has to deal with the construct of his scenario, he has to. And, when we have to, we avoid it.

We, someday, might have to face our own construct. We do not have to reconcile or wrestle with Ikari Shinji’s. As a fictional character made for our entertainment, we can watch what we want, interpret as we will, and forget or argue what trips us up. That was poor writing! They didn’t really mean it that way! You’re looking too deep! They were full of shit! We have all manner of excuses at our disposal to preserve the true fairytale atmosphere of verity beyond verity that is soothing entertainment and confirmation of bias.

Reality vs Fiction.

Neon Genesis Evangelion is not the only work that the series director, Anno Hideaki, has used to approach this gulf of the dissolution of the real. His career is peppered with the interest, from Cutie Honey’s android protagonist to the advertising campaign of Shin Godzilla, which emphasized, “Reality (Japan) vs Fiction (Godzilla).” Nor, is it alone the interest or burden of Anno, as we can find echoes throughout the work of the writers, of episode and single-entry directors, the mangaka, et al.

Outside of manga and anime, it is still a long tradition and a full field. The nearly-nihilistic comedy, Beetlejuice, was repurposed from the narrative of suicides-as-eternal-civil-servant, depressed youth, the anxiety of aging out, polyester, to a children’s cartoon about two best friends and their adventures between the real world and the Nether World. The angry, trapped rapey pedo-vibes title ghost, Beetlejuice, becomes a genderqueer impish bestie, who sometimes girlmodes it as Bettyjuice, to make girls other than Lydia comfortable.

The real world and the Nether World.

The British franchise of Peter Pan and Wendy Darling shares the eternal youth concern with Evangelion, as well as the elucidation of unreal personal constructs, in Peter and Wendy, called Neverland, Never Never Lands, and in early drafts, the Never Never Never Lands. In the Peter Pan stories, these Never Lands are individually tailored dream and hope islands, rewarding individual children. While one of her brothers has an island of birds, another has an island of birds to shoot at, and Wendy Darling has an island with wolves who will be her companions and keep her comfortable as she rests. Wendy Darling, child, dreams of wolves and rest.

Peter Pan’s Neverland is easily embraced, because it rewards something of our anglophone – at least – cultural expectations, with its pirates and “Indians” who are, in fact, sometimes Lost Boys, and Lost Boys who are, sometimes, Indians, et cetera. Jealous mermaids. Helpful, well-endowed fairy geniuses. Girls who need rescuing and then chiding.

Wendy’s Neverland is not embraced, to the degree that even her Wikipedia entry makes no mention of the content or scenario. Like Peter Pan’s canonical capriciousness and lack of empathy.

What happens with Evangelion. We look at international trends, we look at historic trends, we focus on a niche here, a trope, and pretty soon we do not have to worry about whether or not suicide is good.

The similarity between a robot and an illustration of a monster and the illustration of a monster in another distant culture and the Bible, the Dead Sea Scrolls, the atmosphere for the families at Nag Hammadi, the emotional affect of rigid religiosity, the War, all wars, wars to end wars, ends to end wars, death.

A franchise about hiding inside mother figures and wanting to die.

Evangelion is about whether suicide is good.

Shinji’s life is untenable. It is untenable before he is even impressed into war at fourteen. It is untenable before he is buffeted by the awkward erotic projection of his guardian, Katsuragi Misato. It is untenable when his mother dies and before his mother dies. It is untenable when, impressed into combat, he is traumatized by the brutality of the fight. It is untenable to attend school, to be at meetings, to visit graves, to see his father, to sleep alone, to sleep near someone, to ride trains, to stand in fields, to have company, to breathe.

Everyone in Evangelion is borderline suicidal and some are so suicidal they have committed suicide and get brought back, or copied, restored to something of immediate and machine-like use. Evangelion is not a brutalist reality, but it is a brutalist society. A society of meat-scarcity and instant noodle dinners for our heroes. A society stratified on the tinder-like stances of broken generations.

At several turns, in-world and out, the over-eroticization of women and girls is acknowledged for its toxicity, while the cultural drive away from healthy and open sexuality is broached, and in that world, the anxiety of both, the friction between them, breaks some souls, while as an audience they kind of know is watching, largely ignores the lessons and declarations to continue to over-eroticize and infantilize in eroticization every character but mostly those who are women and girls.

This will sell video games & canned coffee.

Shinji masturbating over a comatose trauma victim he knows and loves is hate and fear, social confusion, horniness, disdain. Some of the audience doing it is Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday…

Whether Shinji’s experiences are socially engineered, mechanically enforced, whether or not reality as he knows it is a metaphysical construct, Shinji is suicidal before he is fourteen.

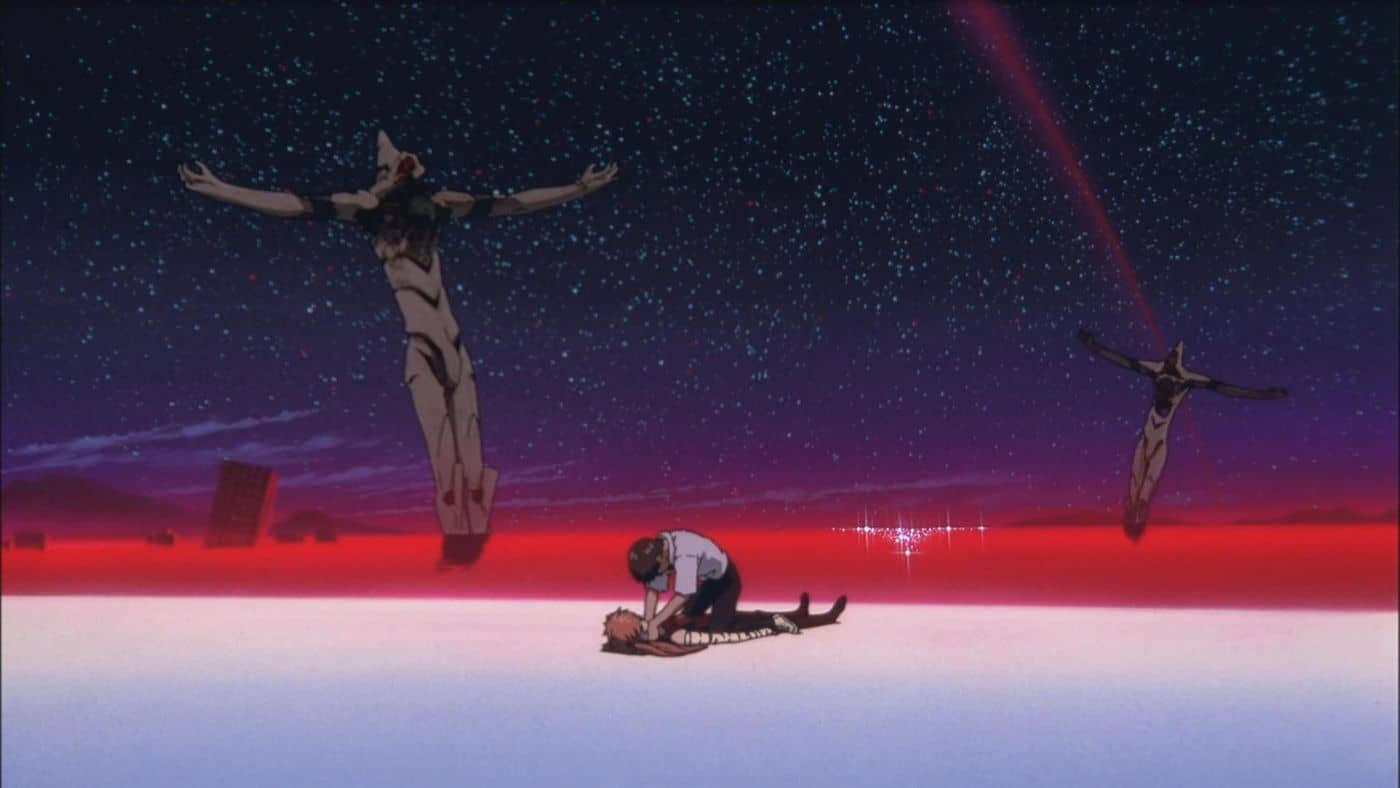

Ikari Yui, Kaji, Misato, Gendo, Asuka, Rei, the other Rei, another another Rei, Kaworu, Ritsuko and Ritsuko’s mom, many an angel and some Evas are all suicides and all murders. We come towards death in this world.

Reality vs Fiction. The real world vs a nether world. Your own small never-never land.

They can be called, angels, apostles, disciples, kaiju; the strange monsters of Evangelion are another form of human being, or another way of humans being. And, the Evas, the massive, slender, armored machines piloted by Shinji and other children, are another kind of human being. The war betwixt is a war betwixt humans disassociated from humanity.

When an Eva begins to tear apart and consume on angel, it is wartime cannibalism. Aggressive. Purposeful. Untenable.

What an Eva experiences, in terms of sensory data, is so experienced by the pilot.

When Shinji’s Eva eats another human being, Shinji has, without choice, without agency, eaten another human being. As a human who would not, by common society, be recognized as a human, having consumed of a human who would not be recognized by common society as a human.

Evangelion, by taking place in the future, allowed audiences at time of release to see themselves in a generation ahead of them. And, Evangelion always spoke direct to the audience. Whether or not homages were recognized, borrowed names, allusions to other television, to comics and novels and history, the franchise engaged its audiences as part of the central metaphysical and political equation. The viewing audience of Evangelion in its early days were possibly closer in age to Shinji and the other teenagers, or felt so, but they were the generations of Misato or the generation of the olds, Shinji’s father, Ikari Gendo. We were not only seeing ourselves in the youths of tomorrow, but seeing our paths in the flawed folks born in 1986 or 1967.

There are audience stages, as there are stages for Shinji, in which Misato or those of her generation seem the most together or the hippest. Kaji is this cool spy sloppy-dresser-but-with-a-tie guy and Misato’s best friend is smart as hell just not smart enough to tell the lesbian three feet away is supremely interested in her. Sometimes it is the elders, that we have a new appreciation for Gendo’s flawed efforts, his damaged hopes, or we have a new evaluation of the sacrifice’s made by Ikari Yui, Shinji’s dead/not-dead mother.

In the more recent movie retelling, called Rebuild, a physical inability to age is added to the plots about being emotionally or socially arrested, but the ending of the television show had already demonstrated how easily time could be reset, how easily Shinji and anyone could be reduced to a less or more mature state or simply an entirely different track of progression. Anno, Enokido Yoshi, Shinji Higuchi, Sadamoto Yoshiyuki and the other central authors of Evangelion were the generation, in Japan, of Children Who Don’t Know War. They were, in fact, the second generation of Children Who Don’t. The specter of being impressed to war, the rite of passage of war, clings to Japanese culture in comparable, and dissimilar, fashion to the reverence and haunting experienced by US culture for the Vietnam War.

To have a new or refreshed understanding of a generation or an age or a person is not to truly reify them or absolve them. It is growth, but it is growth that is not intrinsically linear. Hauntings can recur and recur and this is growth. A television show can spawn video games and pachinko machines and tie-in coffee, without these being linear growth. Spectral growth has affect.

There are many reasons this is official game art. They are all thematic.

In many ways, Evangelion feels more kin to anti-war efforts like Battle Royale or Martin Scorsese’s The Big Shave, than it does to the general run of giant robot cartoons, except that giant robot cartoons are created to be and designed to be an anti-war genre. Evangelion was a return to form, which makes it feel separated, especially as the form was often rejected by other anime after. The Macross and Gundam franchises are anti-war, examinations of better ways, or traumas, of growing and growing up in war, but the intensity comes and goes series to series, product to product. Tomino Yoshoyuki, who created Mobile Suit Gundam, was nicknamed, “Kill’em All,” not because he was offing characters for laughs, but because war scars you and then it kills you. Even if you die a long time later, of old age.

Tomino’s Space Runaway Ideon is a direct influence on Evangelion, which borrowed terminology, plot points, mise en scene eagerly from the 1980 anime about seeing god in giant machines and well-meaningly committing mass murder and rebirthing life itself. Ideon is intently political and so, too, Evangelion, crass and careless marketing tie-ins notwithstanding. The other thing war does – it’s good for the economy! they always cry – is open up marketing opportunity.

“Get in the razor, Shinji.”