Patricia Highsmash

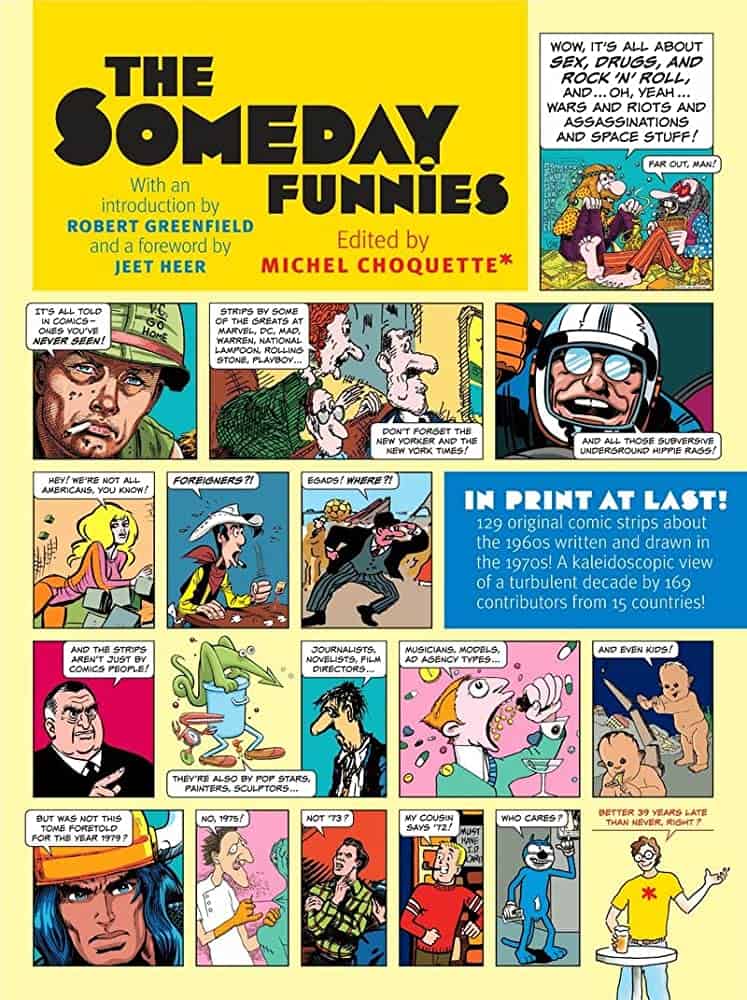

The Fake History of Comics and The Someday Funnies

by Travis Hedge Coke

I think I am under no illusion how difficult I am considered by some colleagues and audiences. Or, if politer, how persnickety I am perceived to be.

I have particular difficulty with received history, supposed firsts, ignored outliers, and the parts of a historical record which are essentially niceties.

It is received – and manufactured – American history that comics are an American art form, created in and “pioneered“ in the United States of America, over the course of the early part of the 20th century. Outside of being polite, or nationalistic, this is bullshit. We all know that it is BS. We all know that it is propaganda which serves a particular politic, that it is manipulative; it is a lie. It is such a lie, that I begin to sound like a cross between a Lisa Simpson parody and a young Spock. This is not entirely appealing as a position, but the history is a lie.

Most of The Someday Funnies were left unpublished for decades. Much of what was solicited and collected for that series was unseen and unacknowledged by the broad swath of casual or intensive comics readers. So, how much influence can they have, and how much am I muddying history by emphasizing them, instead of clearing up the waters as we tread where angels fear?

It is impossible to identify when comics were invented, what culture developed them, but communicating narrative or emotion via visual art and the written word, or the implication of visualization and the written word, is as old as known human history. The word “comic” Is not connected directly to the genesis of comics, but is merely a description of a pre-existing methodology, a pre-existing art form.

Similarly, comics in the United States have been radically more advanced, more developed, more artistic, with a wider range, a greater breath, a variegation that is difficult for us in terms of received history to countenance.

Marketing terms, such as Golden Age, Silver Age, are embraced as historical eras. The Silver Age of comics only really embraces a nebulous handful of years of superhero comics limited to the comic pamphlet or comic book, and to facilitate the adoption of silver as a historical era, we wipe out every part of comics that is not a superhero serial pamphlet. Gone. Off the record. Newspaper strips, Single panel cartoons, book length endeavors, horror, comedy, war comics, westerns, fine art in young reader comics are all wiped clean from the record to maintain an illusion of a pristine era in which the superhero comic — in order to market superhero comics to collectors of superhero comics – is the sole exemplar of comics between 1956 and 1969.

A benefit of this system is that whenever one wants to introduce the idea that comics are maturing or comics are regressing the eraser can be held a little less closely to the chalkboard. If we want to pretend that the late ‘70s or the early ‘80s or 2005 is the year in which comics matured, in which comics developed refined techniques or mature concerns, we just lie about the historical record and we describe it so.

Our routine process is so neurotic and so fundamentally based on bullshit and bullshitting that we can simultaneously describe the 1990s as the lowest era of comics, the death of comics, and the time comics went mainstream; the time comics reached out to more literate and artistic audiences. And all we have to do, in order to present these concurrent but contradictory cases, is to make sure not to say both on the same day, and to pick which comics we use as examples very carefully.

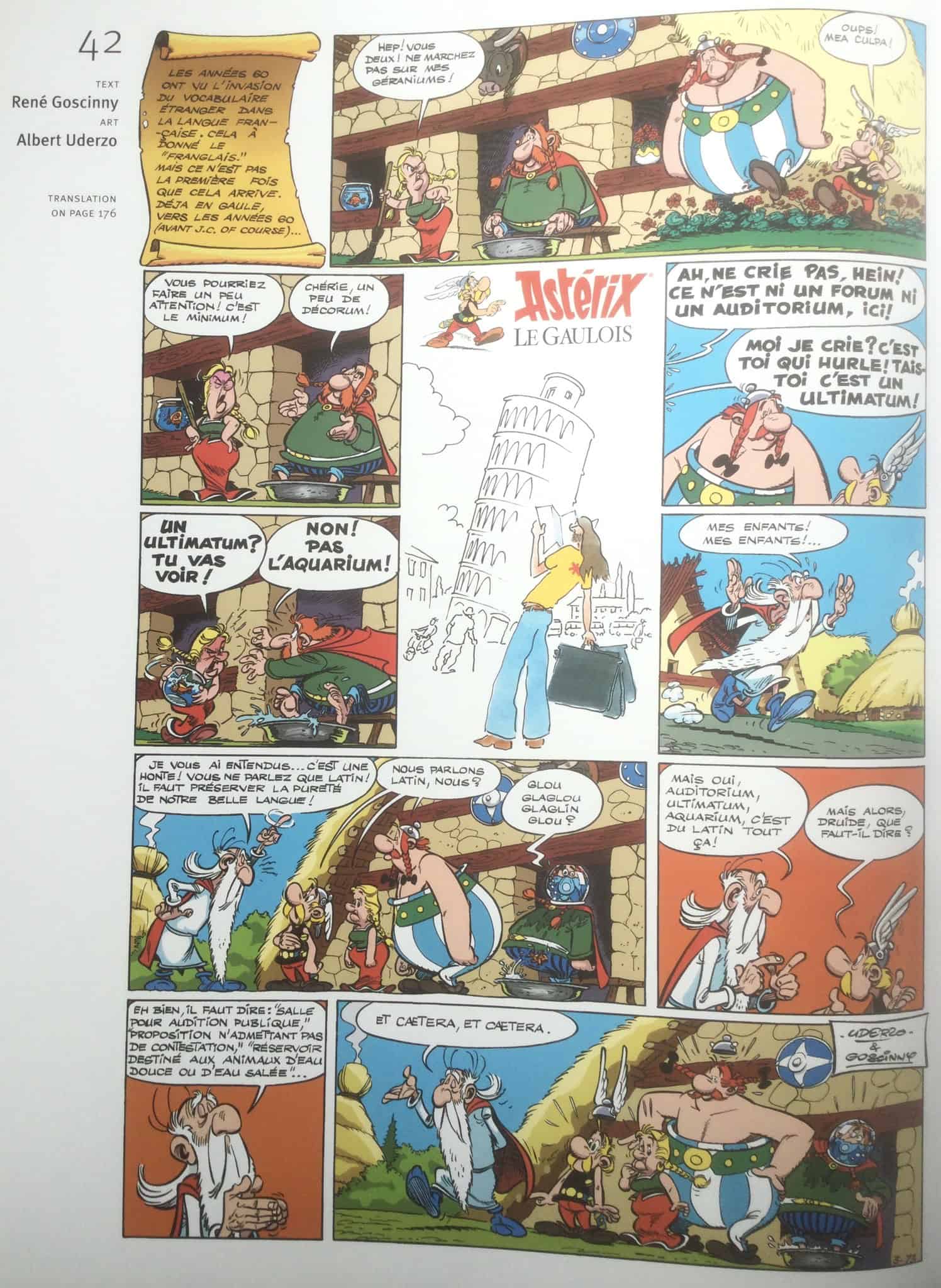

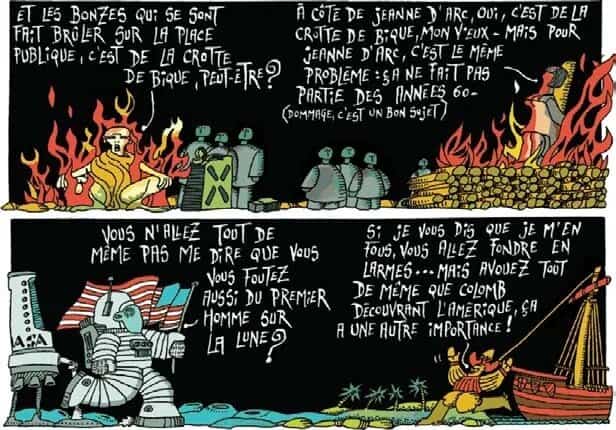

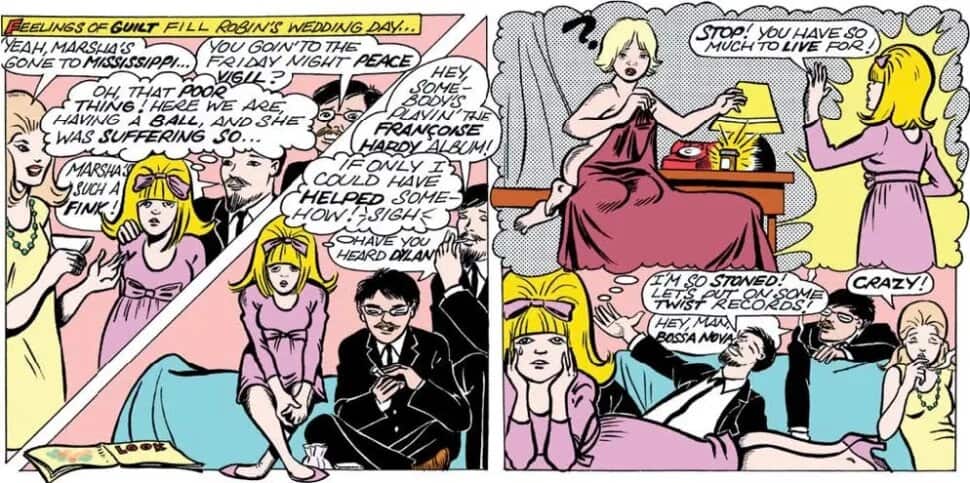

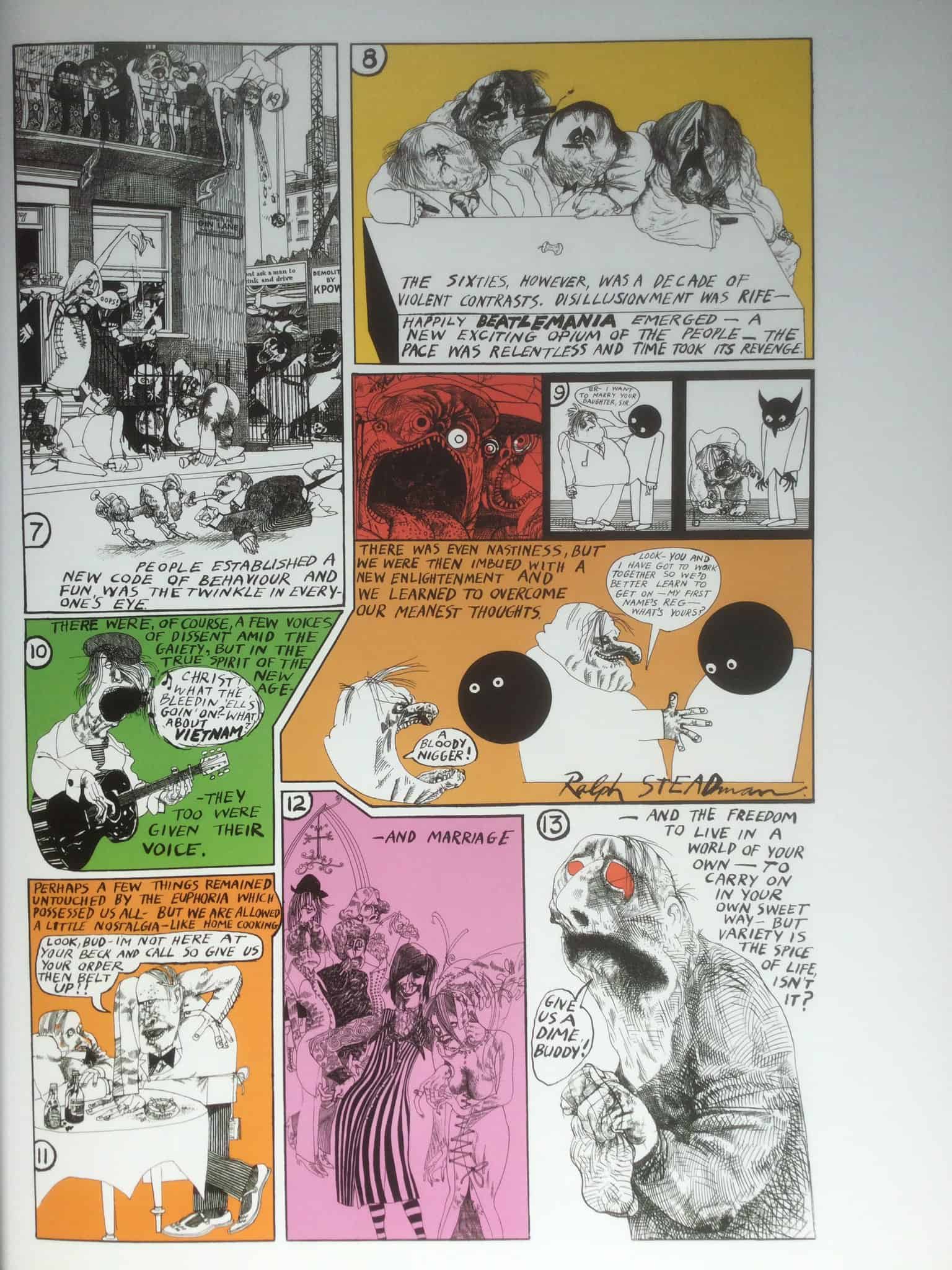

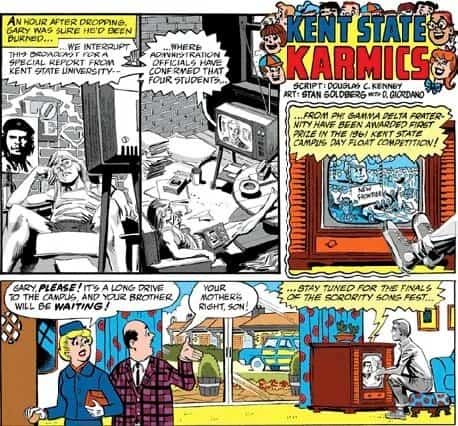

One of the things that I love about the final release of The Someday Funnies, edited by Michel Choquette, is that these 1972 comics about the late 1960s run the gamut from fine arts intellectuals, monthly superhero artists, old-school legends, European artists, underground comix authors, And people who at this point, we have turned into grandpa and grandma.

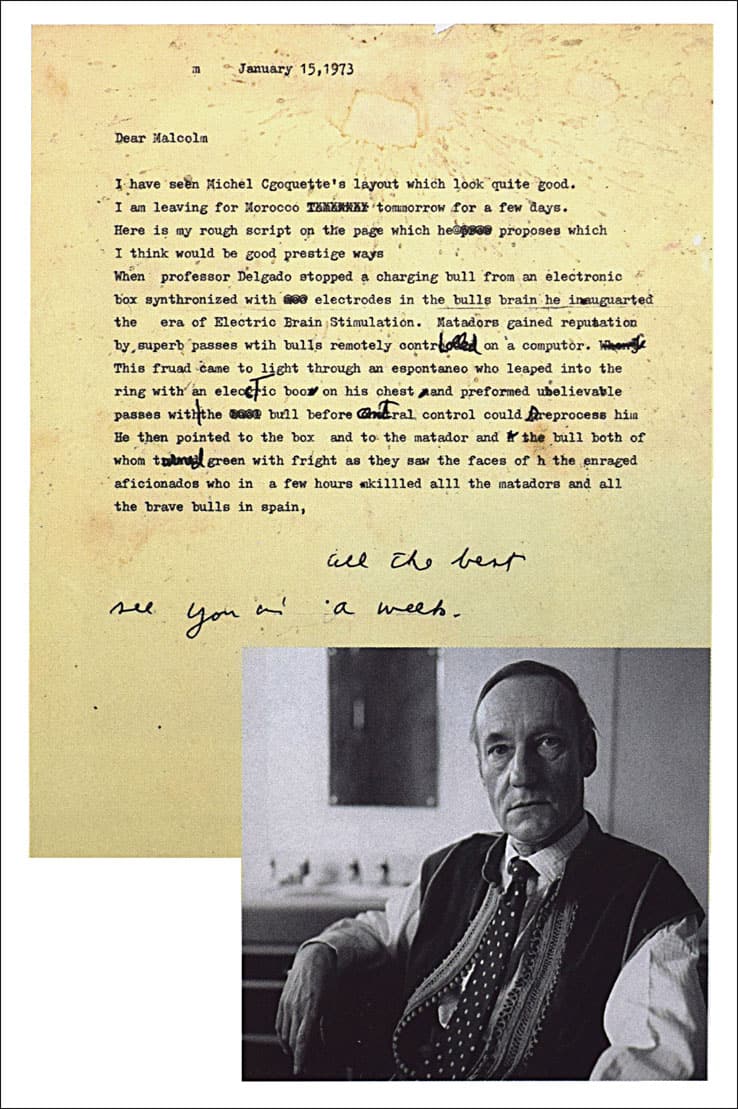

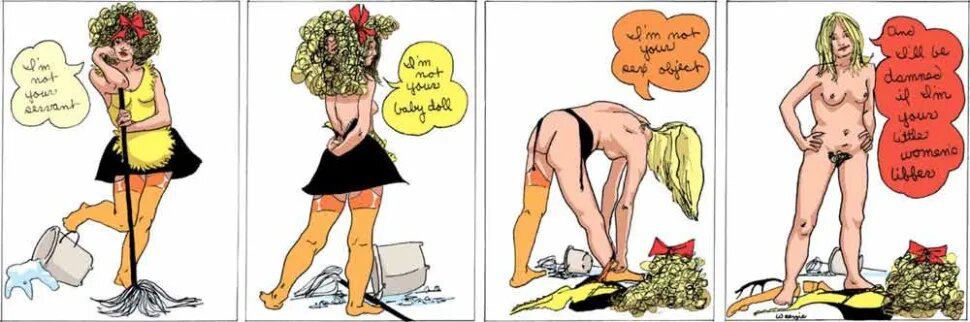

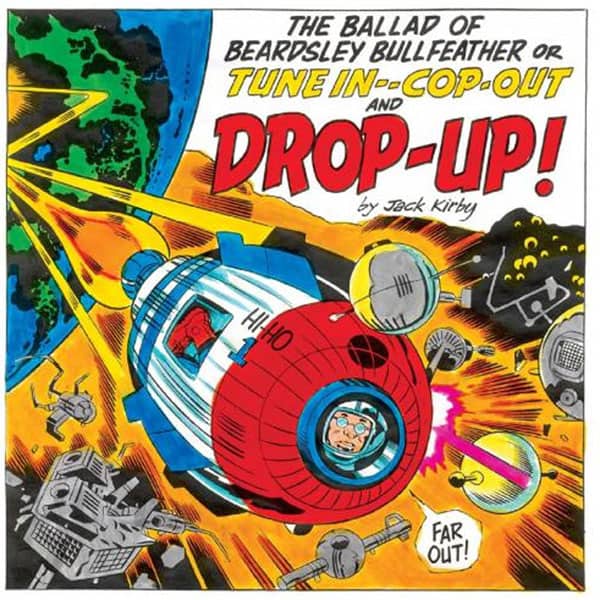

The Someday Funnies collects Dennis Kitchen, Mary Anderson, Jack Kirby, Barry Windsor Smith, Roy Thomas, Louise Simonson, Tuli Kupferberg, Sergio Aragones, William Burroughs, Willy Mendes, Herb Trimpe, and Trina Robbins. Aimed specifically at an adult, hip audience these short comics, running from one panel, to one strip, to two pages, put the light to nearly every illusion we have crafted about these comics authors.

Louise Simonson’s piece is directly sexual, adult, political; it is amazingly feminist even as she declares that she is not the readers “little feminist.” Jean-Claude Forest’s Barbarella and Harvey Kurtzman’s deformed erotica, are no more or less mature or political than Black Tide by Victor Mora and José Luis García-López, Tom Wolf’s two-page The Man Who Always Peaked Too Soon, The Ballad of Beardsley Bullfeather by Jack Kirby and Joe Sinnott, or the six-panel Jeffrey Catherine Jones’ ’69, which immediately follows the Kirby/Sinnott comic.

Here we have in a collection just over 200 pages long, women, queers, foreigners, veterans, young radicals, pornographers, students, men, straights, graduates, collagists, comedians; some of the best, some of the brightest of a century.

A large audience may not have known these comics existed, and even a smaller comics-savvy audience may not have grasped the scale or scope, but the artists and writers and editors knew what they did, and maybe some of what their compatriots had done.

To take stock the one-hundred-and-sixty-and-counting contributors to The Someday Funnies is to wrestle with how much the history we are given is concocted, directed, fraudulent. We are defrauded by the way we have been taught to think about comics, to talk about comics, that we have been taught is polite and safe to talk about comics. It upsets people. It upsets some historians if we say that Dave Cockrum made some horny art. It upsets some historians to acknowledge that women have created political or sexual art and that women are not the fussy, difficult censors of brave radical men trying valiantly to introduce just a bittle lit of sadomasochism and high heels in the children’s superhero periodicals like champions of justice.

It upsets everyone if you stop pointing out who in history of comics really went for censorship, who really went anti-union, who really was abusive, bully, even a rapist. (Real talk: You want to get shut out of conversations about comics and comics history, just name the rapists. They will kick you out.)

In The Someday Funnies, CC Beck returns to Captain Marvel and Billy Batson to tackle systemic racism and the ennui of the hapless white do-gooder taken out of print. Harry Buckinx walks us through sex, politics, and pavement, and does Gray Morrow, and Frederico Fellini reminds us of the importance of passports to some people.

Whether it is Jack Kirby and Joe Sinnott poking at Ayn Rand or Beck, with Denny O’Neil and Don Newton, awkwardly rolling us through the evils of the Ku Klux Klan, the military-industrial complex, police brutality, and uh Black looters stealing a tv and some groceries, everyone has something to bounce off our eyes and the back of our brains. The ‘60s, the ‘70s, the 2010s, 2020s are imperfect and brutal, weird and lovely and tragic. How we choose to call out what we find a problem may have been problematic, too, all along.

Right now, we are back in a phase of it being impolite to say who is being racist or who is being transphobic, particularly if they are over the age of twelve. Twelve is a little arbitrary but I have seen the criticism that a transphobic racist is too old to understand their bigotry or why their bigotry is not super funny but is a problem.

Is an archive of early ‘70s comics about the 1960s, published in the 21st Century an historic artifact, an echo? A Bronx cheer in a bottle in a bag in a city that requires you to bag over bottles for public consumption?

History may not be dead or living, past, prologue, or preview, but we are in the sieve of history. The Someday Funnies helps put the lie to history and histories, the singular or multiplicitly complicit flue of years and monoculture. Kaleidoscope conjecture of hare today and goon tomorrow.