Patricia Highsmash

Us Living in Fictional Cosmogonies

Part XXIII: Time and the Savage Dragon

by Travis Hedge Coke

“I’m tired of the big two placating a vocal minority at the expense of the rest of the paying audience by making more practical women outfits… It’s boring.”

– Erik Larsen, on Twitter, 2015.

Waddayamean because it’s a superhero comic bad stuff has to happen to these three?

Savage Dragon is a serial comic by Erik Larsen and associates, whose main narrative advances close to a year of time for every year of issues released. Most 1997 issues take place in 1997. Most 2015 issues; 2015. It is a comic were very bad things can happen to people and life is a semi-constant crisis.

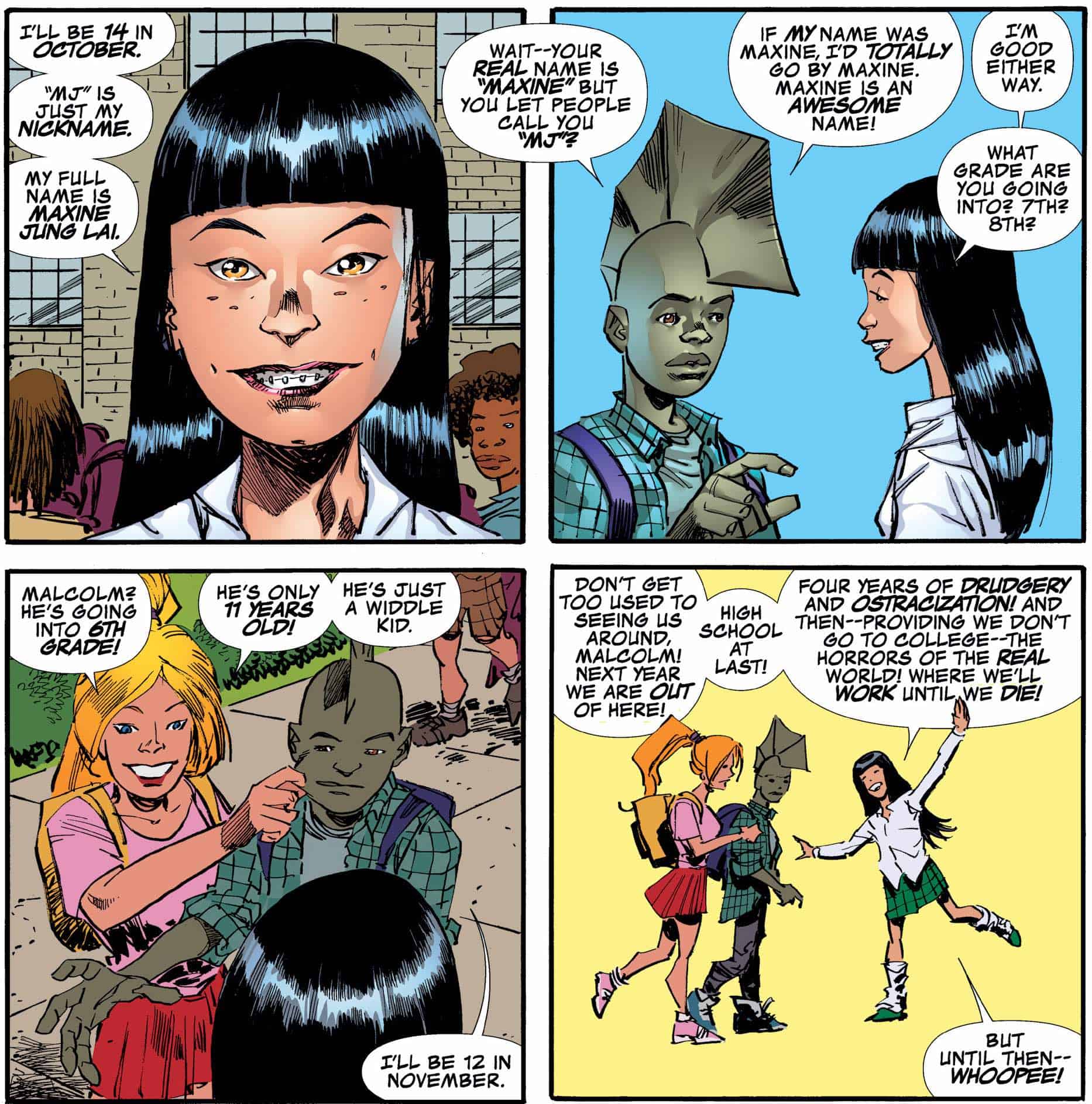

If you read the comics as they are released, that means the characters age in approximation with you. If you read several years’ worth in one go, you can see their maturation and progression. And, if you go back and read a part from years earlier, you may find yourself looking at two children making friends in kindergarten and realize that, in twenty years time, they are going to be traumatized, abused, scarred physically or mentally or both, with futures they could not have imagined, hopes and dreams they would never have fathomed, and an awareness of how bad the world can get.

Aging in real time does make them feel like people.

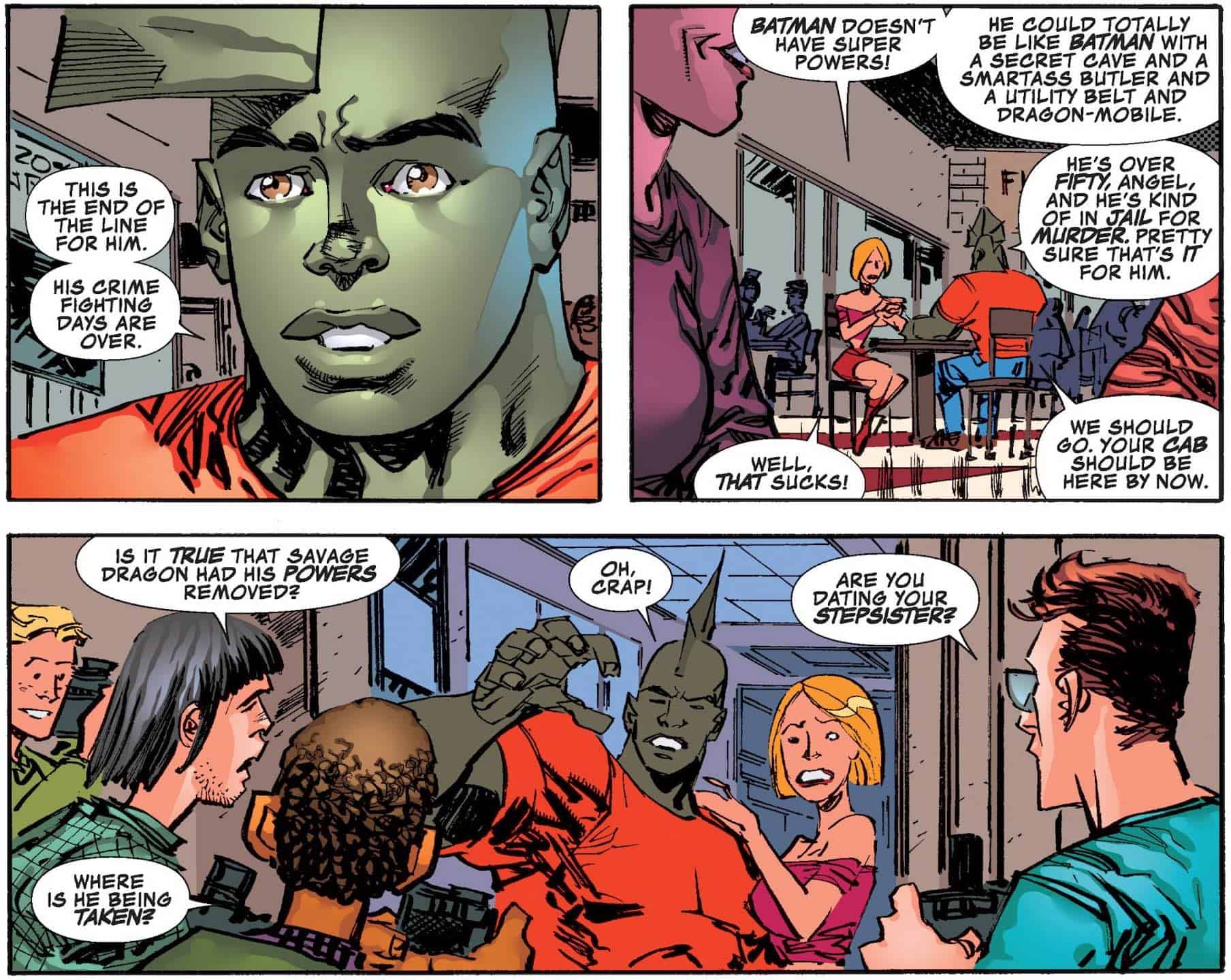

Savage Dragon is a generational saga, a family soap, a police procedural drama-comedy, sex farce, adventure story, horror comic, a romance, a mystery, a science fiction epic. The title Dragon has transferred from Dragon to his son, Malcolm Dragon. Or, maybe it is the ghost of his father in the title, now, since Malcolm has never been particularly savage, and his father was once. Or, twice.

In many ways, Dragon is the Dagwood Bumstead of Image Comics.

Larsen’s world has its origins in comics he handmade as a youth, and even the most recent issues reflect that sense of childhood imagination a willingness to keep making up people even if there is not a strict plot reason for their detailed existence. Dragon’s world has always been big. Always been an entire place. An entire cosmogony beyond the city of Chicago where most of the early comics took place.

Whether the comic is any kind of journal for Erik Larsen is up to armchair psychologists and stalkerish fans, but it is easy to feel like we know what he was interested in at the moment, with each issue, as references to outside media become prevalent or new turns develop in the style of visualization. Too many speculators attempt to make Dragon, the comic’s original protagonist, simply a proxy for Larsen, who has drawn and written every issue, except for one during a publisher-wide gimmick wherein the other Image-founders swapped titles for one month. Even that single issue was shortly after redone by Larsen in his own voice and pencil. They are inextricable, but anything inextricable is only so from certain angles.

We have to think of Larsen, the creator, the driving author, when we think of Dragon, or Amy, or Angel, or Malcolm, of DoubleHeader or that God, that Herakles, Howard Niseman, Powerhouse, Jose Mendosa. We do not have to start believing any of them are a pure, unfiltered, uncritical mouthpiece or eyeball view from the author.

Dragon, and his son, Malcolm, can be jealous, confused, overeager, self-sacrificing, heroic, funny, not funny but they think they are, sad, scared; they can make huge mistakes we and the author see coming without, themselves, maybe ever even feeling they were mistakes.

Larsen has been making stories and art about Dragon and his world, in one or another form, since childhood, and professionally since the 1980s. Even if Larsen’s perspective was represented one hundred percent in the words or actions of Dragon in the 80s, a character now called Paul Dragon, it would be bizarre if they were Larsen or Paul’s perspective now. People have to grow, and with the characters approximating real-time development over the usually-monthly serial issues, the characters are going to change.

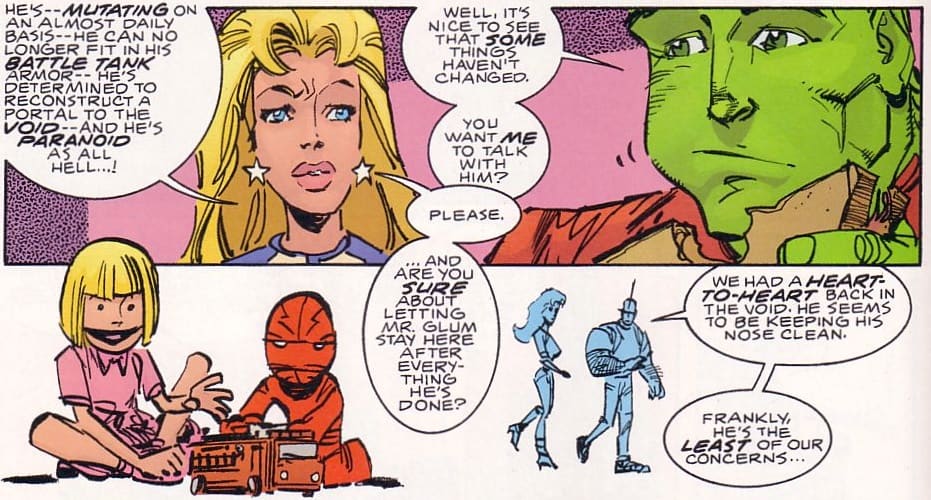

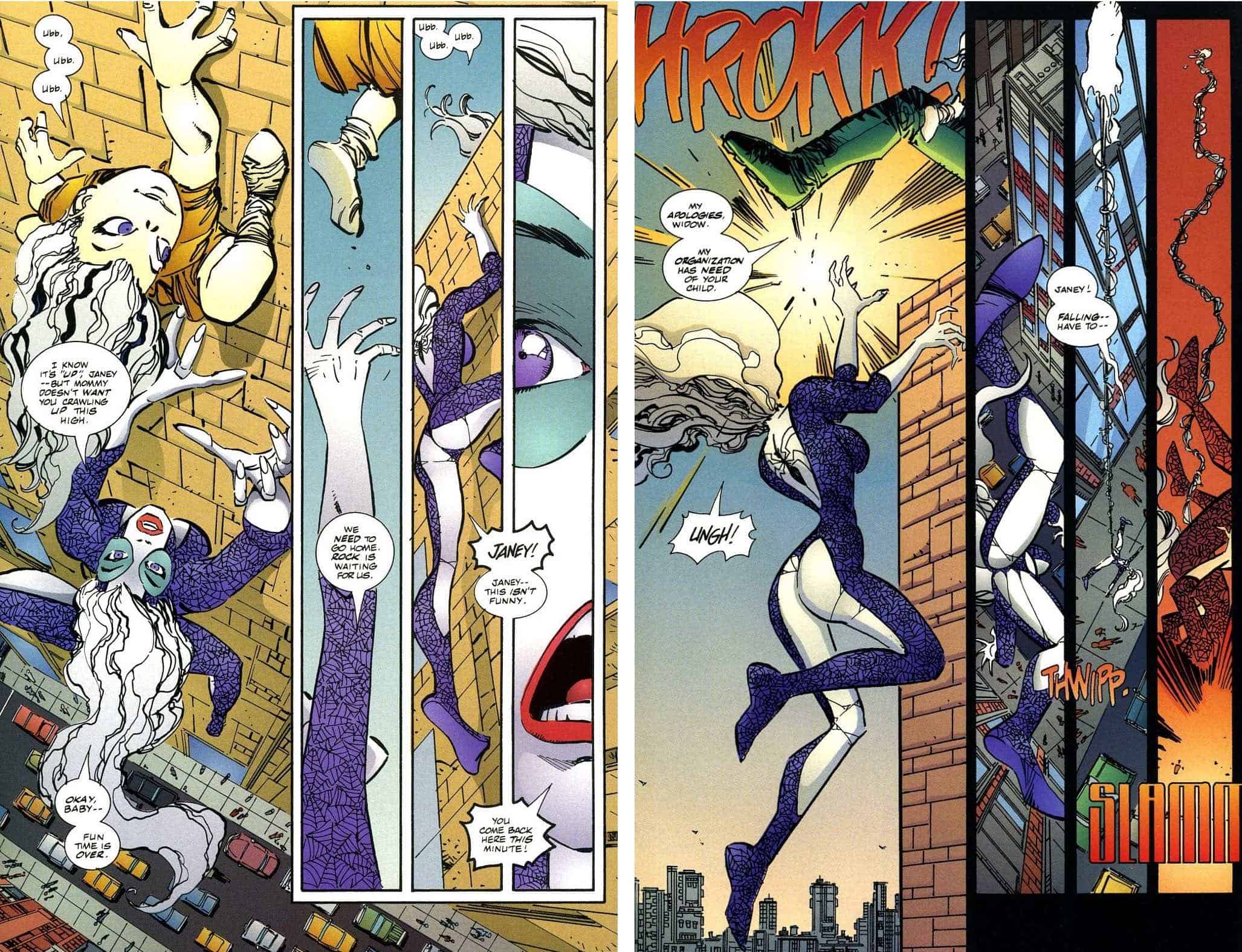

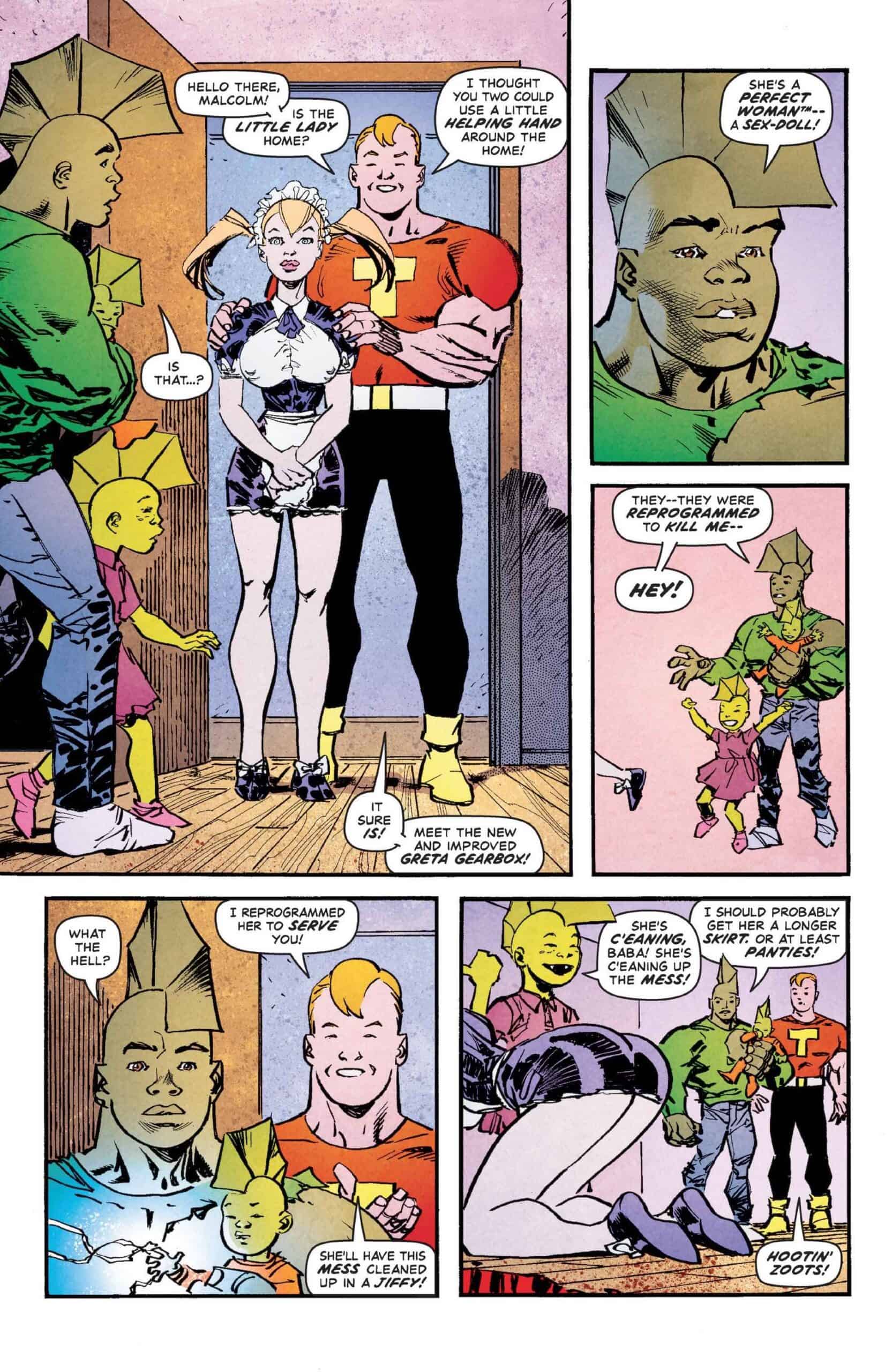

TBF, this is one way you can illustrate her dying.

Savage Dragon is always a cartoon world, run on cartoonish logic and many characters are cartoon-brained, an emotional and action-based logic getting us to the gag, but the emotions and actions feel intensely real – even something like an immature newlywed banking his life, marriage, and career on the chance of having an action figure of himself in stores can be cartoonish and feel intensely real – and the snapback between how gently the comic can shape a life, and how brutally the comic can treat those lives, including children and their adult selves, is potent enough to really shake a reader.

Inside the comic, with this world or set of worlds the only life and logic most of the characters ever know, they may react with less shock than we would, even to pure horror, but this is the way with enough trauma piled on and piled in.

It has been difficult for characters to decide how they feel about Maxine Dragon’s sexual enthusiasm, exhibitionism, or sex addiction, and which they even believe it to be. The quietness of trauma in this world, like ours, leads to speculation along the sympathies of the individual speculating, without any conclusive or omniscient statements. Is her situation, whether addiction or enthusiasm, rooted in dying/nearly-dying and feeling like not wasting chances? Is it self-punishing from feeling doubted and disapproved of by even her loved ones? Is it making sense of her world? Is she just having a good time?

Savage Dragon is a bizarrely healthy comic. Or, perhaps, a Liberal comic. Its characters may not be healthy, or their most potentially functional selves, but people hardly are. Consciously and deliberately diverse in ethnicity, class, politics. The comic itself has no omniscient voice, though, and unlike many of Larsen’s contemporaries, then and now, that lack of an authorial-voice character or a character of authority means, for example, a therapist will never be brought in to validate Character X while maligning Character Y with sexism and bad puns, under the guise of being the knowing voice of reason.

?Layers whoa whoa oh oh!?

Dragon’s world is built around male gaze, but the brain behind the gaze knows there are other gazes. A caricatured character, even one whose caricature hinges on sexual characteristics being well-on sexualized attempts a balancing act of eroticization and humanization without falling into the trap of eroticization meaning someone is less human. There are far harder eye-rolls in comics than Rita having a large chest, and much of the grief she gets or obnoxious behavior from others related to her breasts is clearly on the other parties.

The art has embraced nudity, over time, but penises will not be seen. There is no arguing penises do not exist in the world, I do not especially crave seeing penises in the world, but there is never a sense that an aesthetic is not happening. Dragon’s world is somehow a full aesthetic while never feeling auteur. Control is not parity. Control is not egalitarian.

It’s a choice. Every time.

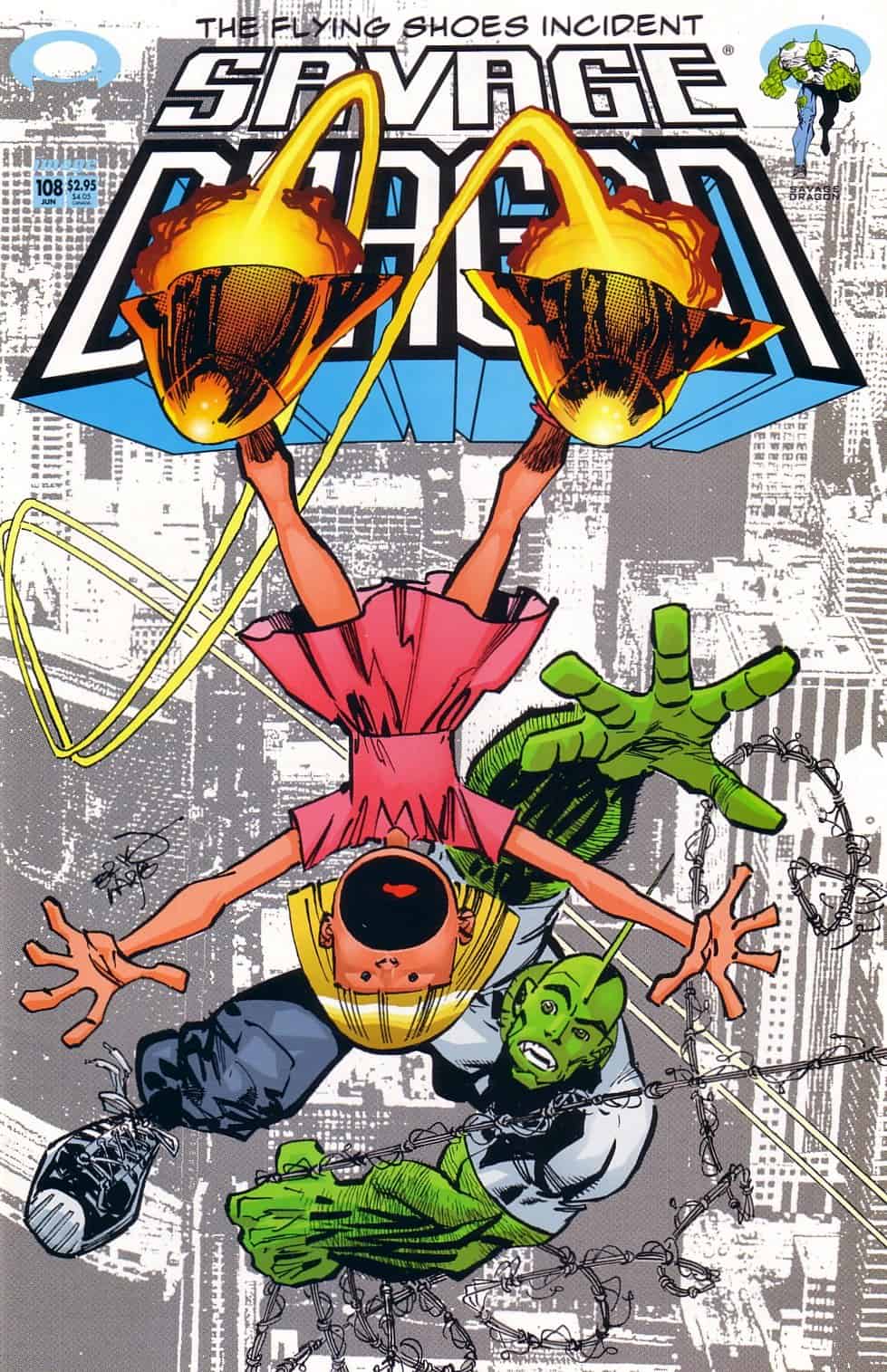

For a stretch, Savage Dragon showed deliberate choices in the artwork, to avoid underwear or upskirt shots of children, something which should be rare in comics but is not. Readers and some speculators who simply see covers or some art posted somewhere online were genuinely incensed enough to complain about one cover, in which a child in a skirt is upside down, flying midair, because she’s put on magic go-flying shoes (Savage Dragon #108, The Flying Shoes Incident), and her skirt stays around her legs. They were not, as far as I can tell, concerned that her hair also looks as if she is upright, nor is her hair moved at all by the velocity with which she travels. Those are details too easily overlooked for these stalwart critics. But, a comic where a skirt does not fly up and show us chonies?

That child’s visual design changes, virtually between appearances, when Larsen moved her to a more cartooned style, variations of which he has explored with different characters and groups in the comic ever since.

Elegant. Articulate. Cartooned. Choices are made.

The visualization, like characterization, world-building, cause and effect and the causes created to garner predetermined effects are deliberate choices. How we deal with a scenario as it unfolds is not always conscious, studied choice, but what we do with the fallout and consequences usually is.

One issue of Savage Dragon has two editions, one titled to distinguish it from the serial title but featuring the same art, same panels, only the point of view shifting, to watch and judge the title character and the main cast of Savage Dragon as he teams up with a national superhero team in his new homeland of Canada. The perspectives of characters are presented without gauge.

My thoughts on Savage Dragon will not finish here. They will age with me, in real time.

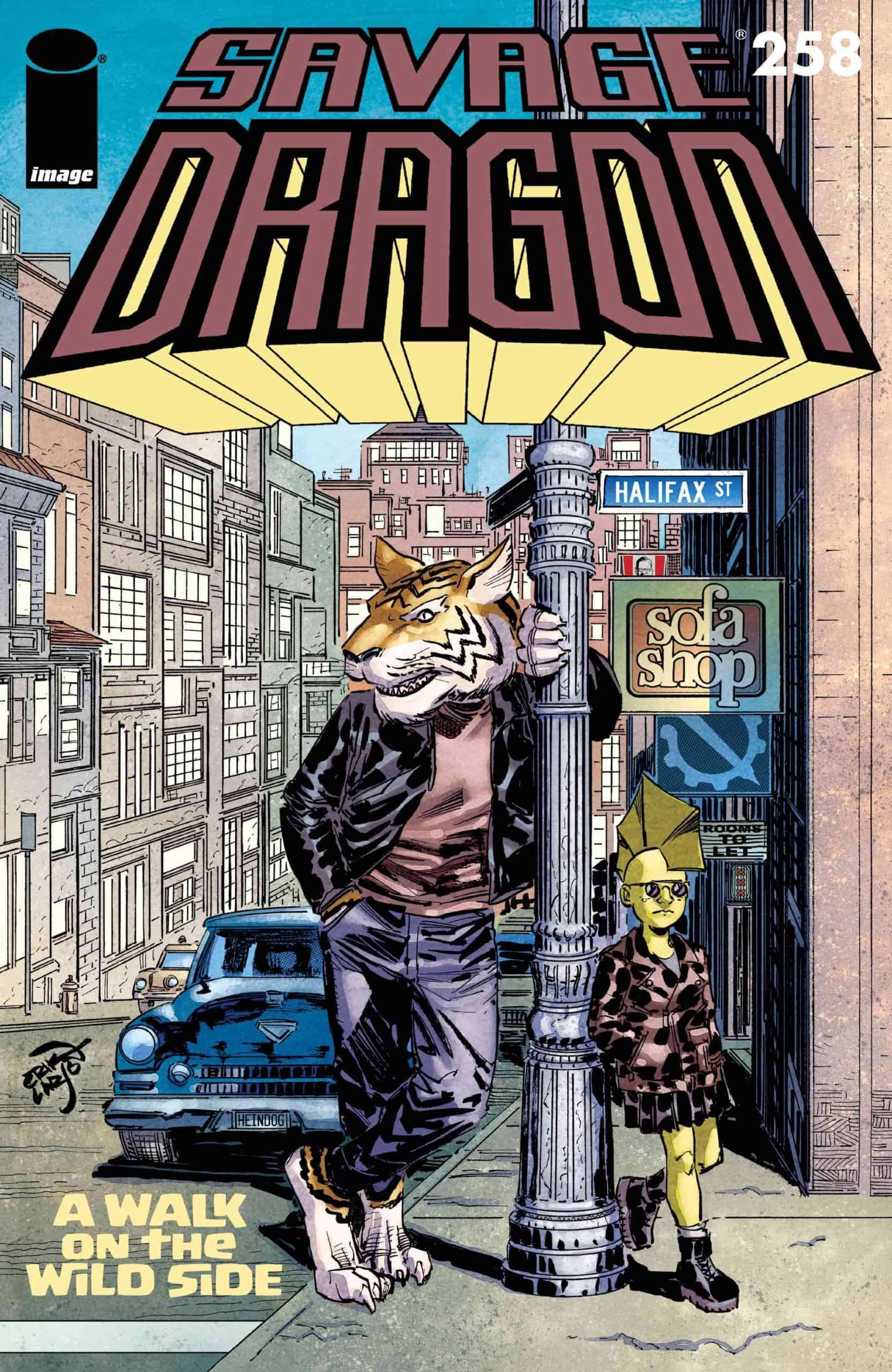

The ability to be wrong is permitted in jarring and comforting effect. Jarring for new audiences, especially. Welcoming and comfortable for routine readers. Mostly. Sometimes it hurts. When Amy Dragon, Malcom and Maxine’s daughter, befriended a homeless, confused tiger-man, I was so nervous at the levels of sexual abuse, sex trauma, abuse trauma in the comic, especially in its recent years, that I had to ask Larsen, myself, if Amy was going to be okeh.

Should I have known?

There is no surety in life of who will be abused and who will not. Who will be hurt and how.

To be hurt is never a moral failing. To be abused is not morally causative.

It may have been rude, but I had to ask. I have no allegiance to pretending these fictional people are real, but they are too real to me not to care. I have been there for every month of Amy’s life, for every month of her father’s, every month of her mother’s life since her mother was in kindergarten. I watched everything go wrong and everyone fuck up, and I saw people get everything right under the worst circumstances.

Someday Amy Dragon is going to own this book. If she already doesn’t.

In its early days, Savage Dragon had the leaders of the most powerful gang in Chicago, maybe in the United States, calling a police to taunt him over the phone like teenagers pranking their boss. We all grow up, and sometimes, so do fictional worlds. Adolescence is weird and can outlast the years it is allotted. Adulthood is no less bizarre, no more certain, not slower, safer, or with less chance we are making a mess.

Erik Larsen assured me nothing like I worried over would happen with Amy and her friend.