Adapting a beloved work of art into another medium is like walking a tightrope with fifty-pound barbells tied to your ankles, especially in the world of gaming. For every success story that manages to meet the monolithic expectations of fans, corporate money men, and the artistic pride of the developers themselves, there is a messy and half-baked failure of corporate greed that disappoints everyone involved. Not every licensed game title can be extraordinary like Batman: Arkham City or Marvel’s Spider-Man; most instead fall into a forgettable pit of abandonment, like Square Enix’s unsalvageable attempt at bringing The Avengers to the world of modern gaming. Even for a massive studio like Square, the pressures of our modern IP hellscape can be too much.

Now imagine you’re a small independent studio with only two titles to your name, being asked to take on one of Western comics’ most important characters, one who stands next to the big mainstream hitters as a near-instantly recognizable fixture of alt-pop culture. Upstream Arcade is that said developer who, in partnership with Dark Horse Comics, was tasked with bringing the world of Mike Mignola’s beloved Hellboy to life in the shape of a video game for the first time since 2008’s much-maligned Hellboy: The Science of Evil.

So, they took the flavor of Mignola’s masterwork and turned it into an original concept titled Hellboy: Web of Wyrd. After spending almost 18 hours with the game, clearing through almost all it had to offer, I can say that it does slip a bit as it walks the aforementioned tightrope of adaptation but makes it to the other side with grace. What’s here is almost perfect, and with some iteration and care, it could become a definitive addition to Big Red’s delicate mythos.

_ _ _

The Story, Art Design, and Music

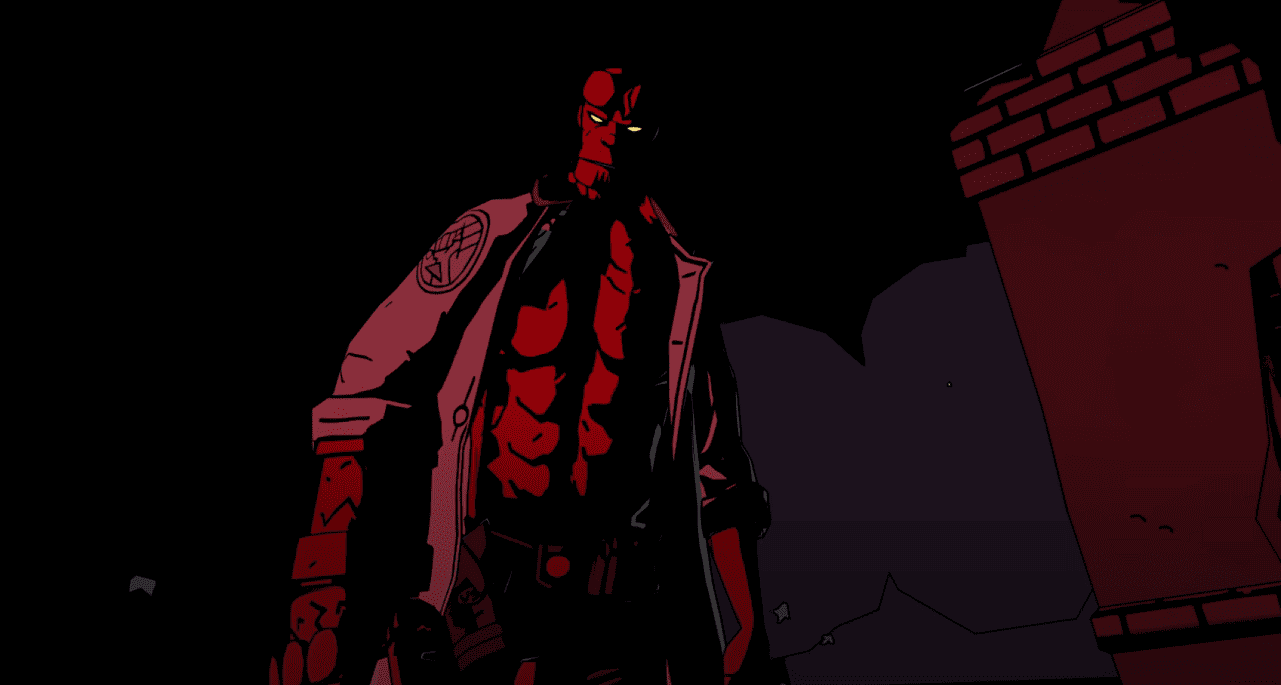

From the game’s announcement, Upstream put on full display their graphical and aesthetic loyalty to the unique art style Mike Mignola brought Hellboy to life in originally. However, it’s easy to mimic aesthetics without capturing the original work’s soul. This is where Web of Wyrd is most impressive frankly, as the entire game is a worthy addendum to the mythos, where it truly does feel like the breathing manifestation of the source material into a different medium. The visuals don’t just jump off the page; they’ve manifested them into a visual experience that’ll remain evergreen.

The soundscape had the most room for error, as the team had proven that they could design the world and UI to be accurate. The team here managed to create an audio atmosphere that perfectly generates the same mood and feelings I had while reading the original series as a kid. The music isn’t omnipresent but it ranges in style to accommodate the game’s range of moods. There’s a thick industrial sense to the combat music and an uncomfortable melancholic drone to the world when wandering through its levels.

The game’s main hub, The Butterfly House, is the biggest example of how much this game achieves in terms of world design. For a wholly original place in the Hellboy Universe, it feels right at home with music that’s and scenery that makes the constant shadows of Mignola’s visual style feel cozy. What brings the whole thing together is how the late Lance Reddick sells us on the personality of Big Red throughout the game.

We’ve seen so many people take on the role of Hellboy throughout the years, but I don’t think anyone captured the comic’s voice for him like Lance. His tone is full of depth, balancing suaveness with Red’s detached sense of grumpiness in a way that showcases the character’s massive range in personality. There isn’t ever an instance of overacting; Reddick’s performance is toned down but not lazy. The rest of the voice cast as well does an excellent job with their characters, especially Pooya Mohseni and everyone else who voices the Wyrd’s ambivalent deities.

So with the presentation nailed, how is the story? Well, mileage is going to vary on what it is you’re expecting from this game. This is a game first and a narrative experience second. While both intertwine with one another to make game progression interesting and satisfying, this isn’t an experience like Marvel’s Spider-Man from 2018 where the narrative absolutely blows everything else about the game out of the water. What’s present, in terms of story, services the gameplay. It gives a reason for what we’re doing and helps to foster the game’s main rogue-like mechanics and does so in a way that’s pretty above average for most games. This isn’t an interactive Hellboy movie, and that’s what makes the story in this game so rock solid.

Hellboy and the B.P.R.D. are looking for missing agent Lucky, voiced by Steve Blum. After investigating this disappearance, the team finds themselves wrapped up in the dysfunction of a strange world called the Wyrd. With mystery and conspiracy dating back to some of Hellboy’s earliest stories, the game sees the player fostering relationships with the B.P.R.D. crew and the Wyrd itself as they trudge through a never-ending fantasy world based on distinct cultural storytelling tropes.

There are twists and turns throughout with some really strong environmental storytelling. Is it the great, medium-defining tale that Hellboy deserves? Not necessarily, but what it does do is tie character and really intelligent environmental storytelling to the game’s main mechanics, so you find yourself caring more about the narrative than expected. It’s really hands-off and doesn’t provide a lot emotionally, but it fits right in among some of Hellboy’s smaller stories. It’s so distinct in its presentation style that the story cutscenes and chapters are treated like the panels and issue-by-issue pacing of a comic book. You will most likely still be left wishing for an experience that had a little more oomph in the storytelling department, but what’s here is full of fun and character.

_ _ _

The Gameplay

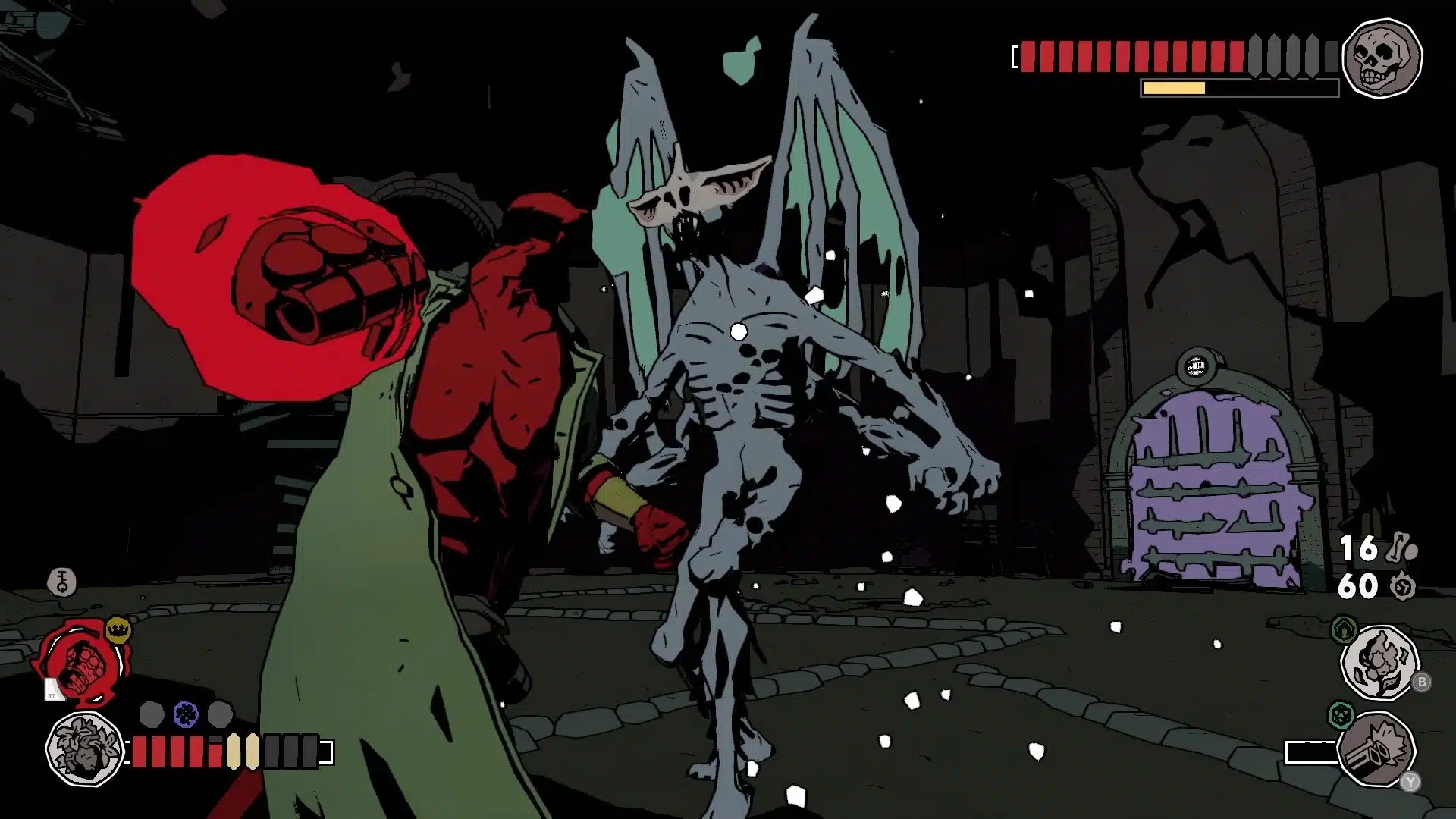

Now, this is where things get rocky. Web of Wyrd is a rogue-like in the most basic of ways possible. There isn’t a lot of depth to the overall gameplay loop as you venture into a handful of aesthetically distinct but not mechanically distinct dungeons. This isn’t a rogue-like that prioritizes creative mastery and player freedom in terms of combat styles to overcome the game’s challenges. Instead, it’s more akin to a procedurally generated souls-like where accessory choices change how you support the mastering of said singular combat style.

For example, the game offers you three gun types and three defensive charms that all do different things on the surface. For example, the grenade launcher packs way more punch than the shotgun, however, it has less ammunition and doesn’t often help with enemy spacing when you’ve been backed into a tight corner. Regardless, your main way of defeating the enemy who’s backed you into said corner will always be the same: Punch and dodge your way out.

Now, I’m not criticizing this exactly. You are forced to truly master the game’s combat in a way that then allows you to get creative within the box they’ve placed you in. It makes the progression experience feel more natural and earned, like you’re outthinking the confines of the game once you really master blocking and close combat. The accessories sugar-coat this in presenting a small illusion of control over combat style that keeps the game balanced.

Sometimes though, the shallow constraints of this gameplay loop begin to rub the player wrong as mindless as the game reaches its final hours. The loop’s engaging for sure, but the bedrock of it is quickly hit before you realize it, especially if you play all the way through to the end. At the root of all great rogue-likes is its repetition being a barrier that’s shattered by player creativity, but the monotonous droning of illusionary customization quickly becomes apparent when you realize that each new environment, save for one deep into the late game, is the same thing with a different coat of paint.

Enemies within these environments do differ, but the approach to defeating them is almost all the same. No matter whether you’re taking in the game’s opening area, The Faithless Kingdom, or racing to destroy Nazi strongholds, you will simply dodge and strike each enemy. This is made tricky by some enemies, such as the Toxic Hair, jump back and keep their distance to draw you in. Yet, the end-all-be-all solution is to simply dodge their attack and attack back. No patterns to recognize, no tactics to really keep you on your toes; perfection simply becomes mindless over time.

There is some strategy needed for when taking on more than one an enemy at once, especially in the late game when enemies that buff other enemies are introduced. This pairs well with the games swarm of Mook enemies, that offer little threat by do hinder your ability to take out the bigger enemies with ease. However, prioritizing an enemy or taking out the Mook can get very clumsy. The game is not designed combat-wise to make fighting off a horde of enemies easily.

You can get tripped up, trapped on terrain, or cornered by multiple enemies without a proper way to handle the situation, and that’s one of the few times death in this game feels unfair. It presents a challenge that you can’t solve. It’s like playing Hyrule Warriors but only being able to use Punch-Out esc combat mechanics.

Bosses do offer more of a challenge, with the diversity in their attack types at first requiring a bit of strategy. However, they themselves fall into extremely similar patterns that make it seem most of their abilities were copied and pasted between themselves. As such, defeating and growing along the game’s difficulty curve can range in satisfaction based on what kind of player you are. Difficult enemies don’t require precise strategy as much as precise stamina.

The enemies become bullet sponges by the late game, but I find this particularly effective for the game’s core loop. It’s about lasting as long as possible, balancing and mastering timing in order to pull off consistent enemy defeats and make continuous dungeon progression. As such, failure stings because often you’re at fault, say when the aforementioned lack of creative combat fails to meet the swarming of enemy AI.

If there was more variety, or if the repetition was more illusionary and way less blatant, then this wouldn’t become such a grueling slog by the end. The opening hours are magical, and what’s here in the game’s shallow systems is well-polished and satisfying for the most part. It just needs to be grown into something more fully-fledged.

_ _ _

Final Thoughts

So, you’re wondering why bother with this at all then if the gameplay is so shallow. Well, it’s still fun in bursts, even if the low-budget price tag really shows in how repetition is used to drag out the game’s overall runtime. Upstream has an excellent, smooth base to build off of exponentially in the future. The biggest problem with this game isn’t that it’s bad; it’s that it isn’t exceptional as a game or as an interactive narrative.

For $24.99 USD, you do get your money’s worth in terms of polish, craft, and hours playable in the main campaign. If you’re a deep fan of Mignola’s world, it’s even more enticing. Its price, lack of predatory monetization systems, devotion to the community, and commitment to quality of life updates and changes make it a game worth supporting. There’s enough care and attention to refinement that makes this adventure oh so almost great, and with iteration, I believe that Web of Wyrd, either through a sequel or DLC, can become a gameplay experience truly worthy of the source material’s legacy.

However, as it stands now, Web of Wyrd is worth checking out but not rushing out to, and due to it being more effective in short bursts, it makes it a perfect game to play on Nintendo Switch or Steam Deck.

Reviewed on PC & Steam Deck