We don’t exactly feel the customary Fourth of July spirit this year at Comic Watch. Whether it’s an all-out assault on reproductive health, the fraying of Miranda Rights, the continuing dissolution of the separation of church and state, the never-ending spate of mass shootings legislators who to do anything meaningful about it, it’s safe to say that America has seen better days. Heck, we may just closer to full-on autocracy than anyone would like to believe if future SCOTUS cases are any indication.

With all that said and in mind, it’s worth noting – the American Experiment isn’t over until we say it is. We implore you to not sit idly by and watch as equality is stripped from everyday life and replaced with a tyrannical Christian nationalism. Get out, get into good trouble, get involved, and vote like your freedoms depend on it.

Because they do. The bad guys are winning… but they don’t have to be.

With all that in mind, then, instead of the predictable “here’s some great Captain America stories” Independence Day rhetoric, we’re presenting ten comic stories or series for you that unflinchingly dig into the dirty underbelly of the myth of the United States. Some are historical fiction, some present-day, and a couple present an all-too-real future scenario that could easily be extrapolated from current events.

10. The American Way

Before he’d won an Oscar for 12 Years a Slave or given the world a Black Batman, screenwriter John Ridley was just breaking into comics with The American Way. A sly allegory for 1960s/70s U.S. politics and race relations, The American Way miniseries (with art by Georges Jeanty) introduced readers to the Civil Defense Corps, a team of government-funded superheroes and their handlers, the Federal Disaster Assistance Administration. However, the whole thing is a sham – all of the CDC’s battles are staged for the benefit of earning the hearts and minds of the adoring public as a means of controlling the populace through feel-good propaganda. When the CDC’s leader Old Glory accidentally dies in mock battle, his replacement, New American, is secretly a Black man – given “gene therapy” to modify his appearance because 1962 America isn’t ready for a Black superhero. An alternative-history look at America during the Civil Rights Era, The American Way doesn’t shy away from America’s racial history and turns a deservedly uncomfortable spotlight on the lies that kept (and still keep) society divided racially into haves and have-nots.

9. Superman Smashes the Klan

Adapted from the 1940s serial of the same name, Superman Smashes the Klan is exactly that: Superman going head-to-head with the Ku Klux Klan. Updating the story to reflect the hate crimes perpetuated against AAPI-Americans since the outbreak of the Coronavirus and the then-president’s blatantly racist attacks on that community, author Gene Luen Yang and artist tag-team Gurihiru don’t shy away from addressing racism in America but don’t give in to easy answers, either. Don’t let the deceptively simple art fool you: this is a mammoth of a story that looks systemic racism in the eye and doesn’t blink.

8. The Good Asian

Speaking of anti-AAPI sentiment in America, it isn’t exactly a new fad. Set in 1930s San Francisco, The Good Asian is crime noir steeped in the all-too-real history of anti-Asian laws and sentiment in the United States. From the Chinese Exclusion Act (and before) to gross “yellow peril” stereotypes to the eventual Japanese internment camps of World War II, the United States has an extremely negative history toward its AAPI citizenry that is typically swept under the historical rug. Pornsak Pichetshote and Alexandre Tefenkgi’s tale of Chinese detective (based on America’s first) Edison Hark’s journey through Chinatown to find a missing woman is rife with institutionalized racism, fear, politics, and the dirty laundry of the American Dream. Twisty in its execution but clear in its message, The Good Asian is a master class not only in storytelling but in diving into America’s racist past in a way that directly ties it to present day.

7. The Department of Truth

Conspiracy theories and the United States go hand-in-hand as a matter of course. Whether it’s “Elvis is still alive” or “they faked the Moon landing” or “9/11 was an inside job” or “Q is telling me that JFK Jr. is alive and well and is going to emerge as Donald Trump’s running mate,” America loves doubting its own reality. But why? What if all that misinformation was serving a purpose, and the things we believe to be real are made that way because of our belief in them? That’s the premise of The Department of Truth, currently ongoing from Image, author James Tynion IV, and artist Martin Simmonds. Proudly hearkening back to early-era Vertigo in its execution (particularly Simmonds’ evocative Dave McKean-esque art), Department of Truth is bleak, dark, and will make you question everything you think you know about American history. Or is it actually shining a spotlight on truth instead? Never quite settling comfortably between fact and fiction, Department of Truth demands to be read in a dimly-lit office with an “I Want to Believe” poster firmly tacked to the wall.

6. DMZ

Taking place in the years after a brutal second civil war has ripped the United States to shreds, Vertigo series DMZ takes place in Manhattan, declared a demilitarized zone by both sides of the conflict. The result is a lawless land where anything goes, the citizenry left behind are forgotten and threadbare, and society has at once devolved into a feudal land of fiefdoms but at the same time is a reflection of our own fractured society. Can the differing factions make peace and learn to work together for their own survival, or will competing interests pick apart the carcass of America from the outside? Written from the detached perspective of journalist Matty Roth, DMZ is raw, grim, gritty – and a near-perfect microcosm of the very real specters of the Confederate past (here, the secessionist Free States of America) and its flawed but Union-adjacent present.

5. American Flagg!

Howard Chaykin’s coming-out announcement as a provocateur par excellence in the early 1980s was one hell of an opening statement: part sci-fi series but mostly a blistering political satire of the Reagan era. Set in the early 2030s, a series of cataclysms has resulted in the U.S. government – along with the heads of all major corporations, of course – relocating to Mars. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union collapsed and Islamic insurrectionists seized power, along with the Pan-African League and the Brazilian Union of the Americas becoming the new global superpowers. But the remnants of the United States government and their corporate backers have a plan: Plex, an interplanetary union baldly concerned with one thing and one thing only – money. Leading man Reuben Flagg, a former TV star, witnesses Plex’s widespread corruption first-hand, and seeks to reveal the truth at any cost. With its unsparing look at the cost not only of unchecked capitalism but also the corruption of money in politics, American Flagg! is a can’t-miss for the disaffected.

4. The Other History of the DC Universe

There’s no getting around it: the DC universe’s history on page is very, very very white. And when they did start making earnest efforts toward inclusivity (Black Lightning, Bumblebee, et al.), it was years after Marvel had already made strides with Black Panther, Falcon, and others. Sure, John Stewart had been introduced as Hal Jordan’s backup, but he was hardly a regularly recurring character. John Ridley, a writer of astonishing depth and nuance (and the only one to make this list twice), saw that whitewashed history and asked: what did all that whiteness look like from the perspectives of the minority characters inhabiting the DCU? Other History set out to tell their tales, from their perspectives. Uncomfortable at times but nonetheless urgent in its message, Other History reads more like an illustrated novella than a traditional comic. Artist Giuseppi Camuncoli does an astonishing job juggling the narrative flow of Ridley’s prose; each double-page spread is less a series of panels and more a piece of symbolic and allegorical art. The Other History of the DC Universe has a one-and-done structure, witheach issue focusing on an individual character: Black Lightning, Mal Duncan (with Bumblebee), Katana, Renee Montoya, and finally, the next generation, Anissa Pierce. And while their stories are uniquely their own, the underlying tales of marginalization are uniformly American. The Other History of the DC Universe is a critically important read, giving voice to the voiceless in a time that desperately needs those left behind to stand up and make themselves heard.

3.Secret Empire

The 1970s were a decade of turmoil: loss of faith in institutions, civil unrest, an increasingly unpopular conflict in Vietnam, gas shortages, recession. And then there was Richard Nixon: never before had an American President faced the certainty of impeachment for actual, tangible crimes. Sure, Andrew Johnson had been impeached, but that was largely political in nature – and he’d survived the process (though barely, by only one vote). Nixon, on the other hand, had directed the break-in of his political opponents’ headquarters and orchestrated the theft of documents, all for his own political gain – these were easy-to-understand concepts that every American could grasp, and there was no way he wasn’t going to be impeached and kicked out of office in disgrace. History was in the making, and what it was making was a very nasty stain on America on the eve of her bicentennial celebration.

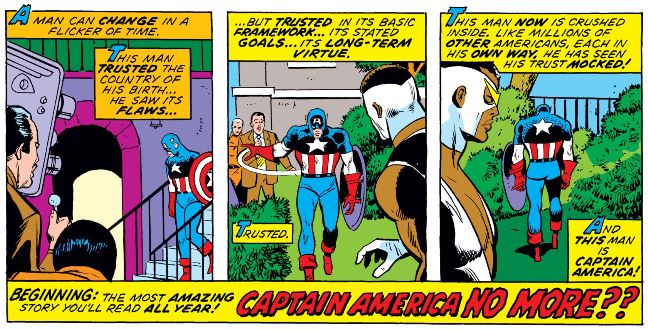

When “Secret Empire” was published in Captain America #169-175, Watergate was a freshly-unfolding conspiracy that brought down an entire presidency. But it was also a product of timing: Nixon left office in August 1974; “Secret Empire’s” finale, in which the President is unmasked as the head of a nationwide conspiracy to undermine and take over the United States, only to kill himself rather than be exposed (sorry, forty-eight year-old spoiler) – was published just four months earlier. That eerie confluence of life imitating art made “Secret Empire” an instant classic.

Even if that hadn’t been the case, though, “Secret Empire” is a fantastically fun story in its own right. The Secret Empire organization manages to frame Captain America for murder, leading to a nationwide pursuit. Cap, in turn, not only has to expose their conspiracy but also clear his name – leading to that ultimate exposure of the President, who is definitely a stand-in for Nixon, to be revealed. Writer Steve Englehart was one of the best writers of his era, on the vanguard of a new generation including Marv Wolfman and Len Wein and Steve Gerber that were not only weaned on superheroes growing up but part of a more socially-conscious movement within the genre itself. Along for the ride was journeyman Sal Buscema on art, bringing his trademark clean lines to each issue with a clean, easy-going ease. Together, they crafted a classic for the ages that spoke not only to the times it was published in, but to the underlying anxiety and corruption at the heart of America itself.

“Secret Empire’s” aftermath was similarly seismic – his faith in America shaken, Steve Rogers gave up his mantle and instead became Nomad, man without a country. And although Rogers would of course become Captain America again, Englehart’s message was clear: an America without a moral compass was no America at all, and could be served by no symbol. But that didn’t mean its people couldn’t still be fought for.

2. Uncle Sam

Nobody knew what Alex Ross was going to follow up his career-defining magnum opus Kingdom Come with, but it’s fair to say that nobody expected Uncle Sam. Published through Vertigo in 1997 and only two oversized issues in length, Uncle Sam was an incisive, cutting blow to the myth of America and the unyielding corruption of the American Dream. Who is America for? Does it live up to its ideals? Is it even built to, or has it been on the hustle all along? These are questions that have no easy answers, and Ross and co-author Steve Darnall used Ross’s photo-realistic painting style in a new way, working allegory after allegory into each page to maximum effect.

The story follows Sam, a homeless man who may or may not be the actual Uncle Sam – or so he believes. As he struggles to survive the increasingly hostile environments, his mind darts back and forth from memories both real and imagined from his life – but also, America’s darkest moments, from lynchings to Tammany Hall corruption to institutionalized racism to slavery and Jim Crow to the Dust Bowl and the assassination of JFK. As Sam tumbles helplessly through the confused imagery of his mind he can’t help but wonder: where did America lose its way? When did it abandon its ideals? Or did it ever take those ideals seriously at all?

Was the myth of the American Dream ever anything more than a myth at all?

Uncle Sam offers no easy answers, even as Sam moves to confront his own doppelganger – a slick, oil-rich, war-hungry capitalist decked out like some kind of spit-shined parade float; pretty on the outside but a moral vacuum within. And yet, as the narrative unfolds, this version of Uncle Sam is presented as every bit a “real America” as is the idealism that Sam strives for, inevitably leading to a clash between the two for the soul of the nation. Does either of them have the right to define America? Who’s right, and who’s wrong? Or are they both halves of the same coin? As America struggles with itself in real time for its future, and to define what it is and who it’s for, Uncle Sam feels more than ever like mandatory reading.

1. March

There’s comics that tear into the American firmament, and then there’s March. The late Congressman John Lewis (GA-5), along with co-author Andrew Aydin and artist Nate Powell, brought to life his story in stark, black-and-white detail. Starting with his childhood in the Jim Crow South, Lewis endured a life of oppression under the thumb of a society deemed as his “betters” both institutionally and socially. The story of the Civil Rights Movement is one that has been recounted numerous times across multiple media, but never before in comics had it been given such breathtaking and heart-rending treatment from someone who was there first-hand.

Published by Top Shelf Productions across three volumes, March is brutal in its depiction of not just racism in America – but racism as one of its defining features, the quiet part we don’t say out loud but is omnipresent nonetheless.

And yet, as a work of historical fiction, March is ultimately optimistic in its tone – yet cautious, as well, that the rights the men and women of the Civil Rights Movement fought and bled and died for could be taken away swiftly if Americans grew too complacent – or if the forces it was fought against exploited the system itself to circumvent its freedoms. Lewis proudly marched alongside Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and so many others with the notion that America wasn’t living up to its ideals – that it could be better. That it should be better. That was work that Lewis continued as representative of Georgia’s Fifth District until he died in 2020 amid a sweeping move toward authoritarianism at the highest ranks of our government. And yet, in the end, he remained optimistic about our nation’s future: “Get in good trouble, necessary trouble, and help redeem the soul of America,” he famously extolled.

The present tense of that statement infers that Lewis believed in the inherent goodness of America, but that it was – and would continue to be – an ongoing project. That understanding of the urgency in refining the American Experiment echoes throughout March, from the Freedom Rides to the sit-ins to the beatings and verbal abuse and awful day-to-day aggressions Lewis and so many others endured – and still endure to this day – is the core of Lewis’s being and legacy. The last remaining member of the Big Six of the Civil Rights Movement, Lewis was a link to our past, and March tells his story with an urgency that reminds us all that the work is never done. The American Experiment persists because of men and women like John Lewis; maybe his spiritual successor read (or will read) March and will be inspired to continue his legacy of good trouble – and in doing so, continue the work of making a better, freer America for us all.

Happy Independence Day.