Thanks, in part to 2001: A Space Odyssey, the 1970s saw a change in visual and special effects. The quality of miniatures and the improvement in film technology made innovation possible on a much larger scale. During a kind of recession in the industry, many of the larger effects houses closed and several of their technicians became freelancers. Some even went on to found their own companies specializing in particular effects or techniques.

A greater distinction between visual effects and special effects also came out of the 70s. A special effect is very often a practical, or physical, effect while visual effects are often created in the post-production part of the media. It’s the difference in creating a stop-motion dinosaur the way Harryhausen did and creating the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park. Both are good effects but come about in very different ways. They also influence an actor’s choices in very different ways, as well.

Technology was also changing in the early 70s. The IMAX system premiered in 1970 with the film, Tiger Child. This seventeen-minute film introduced audiences to a different movie-going experience featuring different screens and viewing options.

Stanley Kubrick was the first to use Dolby sound technology, and noise reduction for his film, A Clockwork Orange in 1971.

Also in 1971, The Andromeda Strain was a kind of science-fiction, techno-thriller which utilized computer graphics in a way audiences had not seen. Douglas Trumbull, who worked on 2001: A Space Odyssey had $250,000 to spend on special effects. This film had one of, if not the first use of computer rendering.

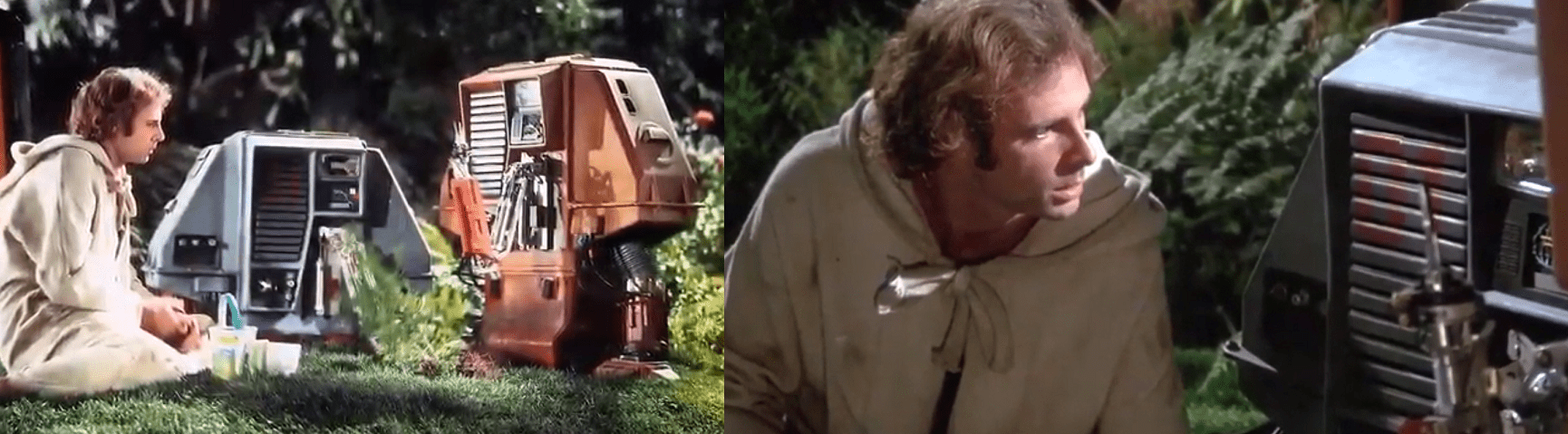

Trumbull worked on Silent Running in 1972 where he used an idea Stanley Kubrick had about a sequence involving Saturn. After developing the sequence, himself, Trumbull used it for Silent Running.

A Korean war aircraft carrier, the USS Valley Forge, was a decommissioned vessel docked at the Long Beach Naval Shipyard. Interiors for the film would be filmed there. The large, open space gave the scenes an organic, natural look, not the work of a production company, even though it was.

Not long after the filming was completed, the carrier was scrapped. Forest environments for the film were shot in Van Nuys, California. The geodesic domes were based on the Missouri Botanical Gardens Climatron dome. One of the geodesic domes resides in the Science Fiction Museum and Hall of Fame in Seattle, Washington.

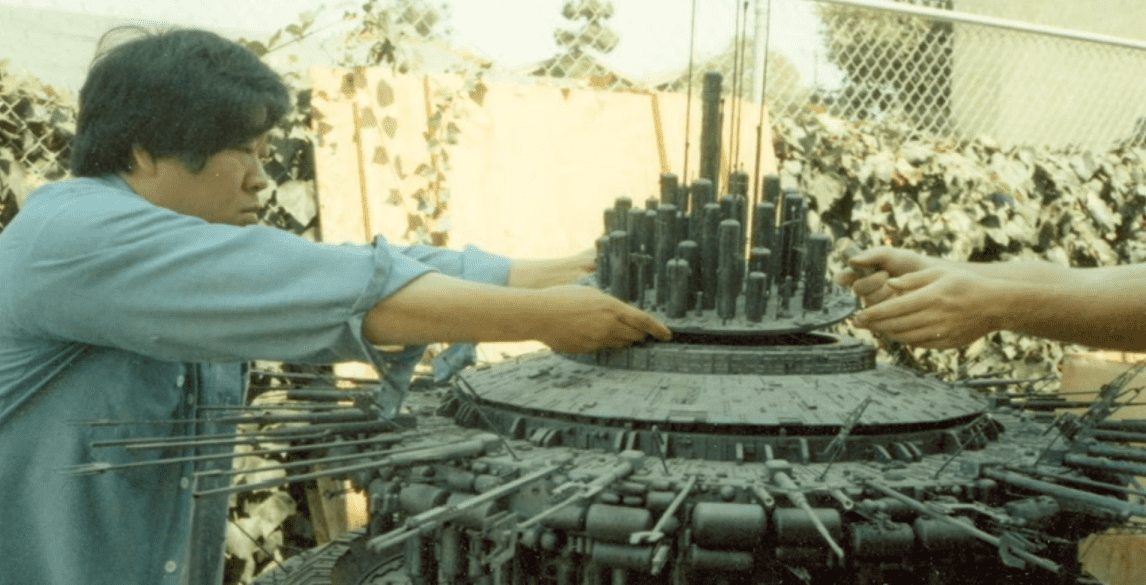

The model for the Valley Forge measured twenty-five feet long and took over six months to construct. It was made from a combination of custom castings and some eight hundred prefabricated model aircraft and tank kits. Special care had to be taken with the finished piece because of its fragility.

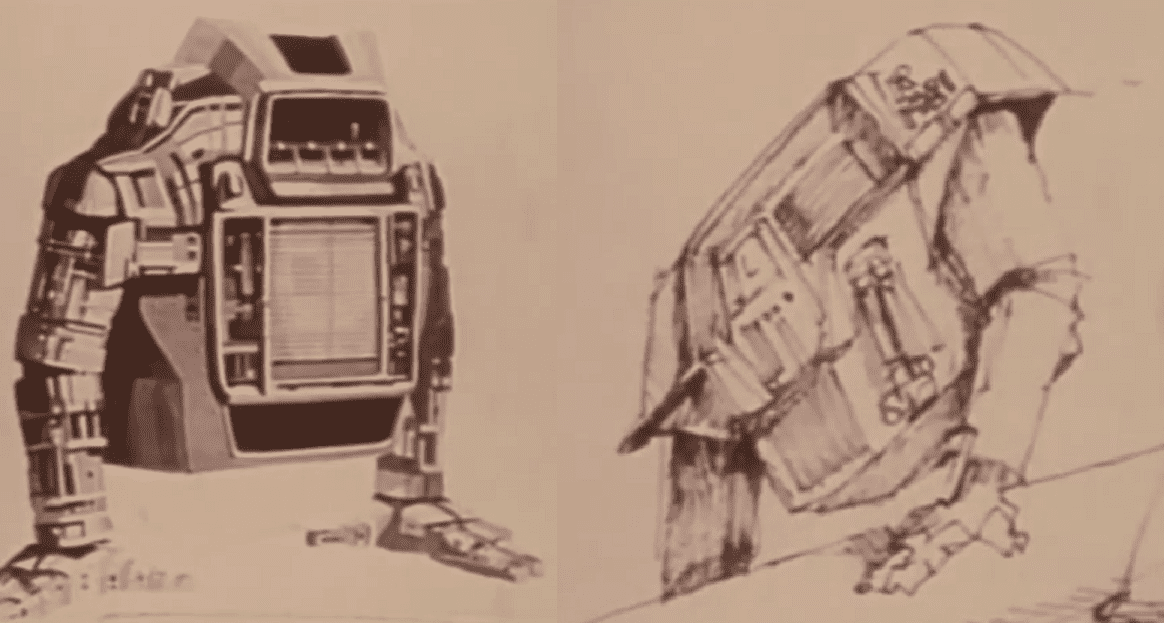

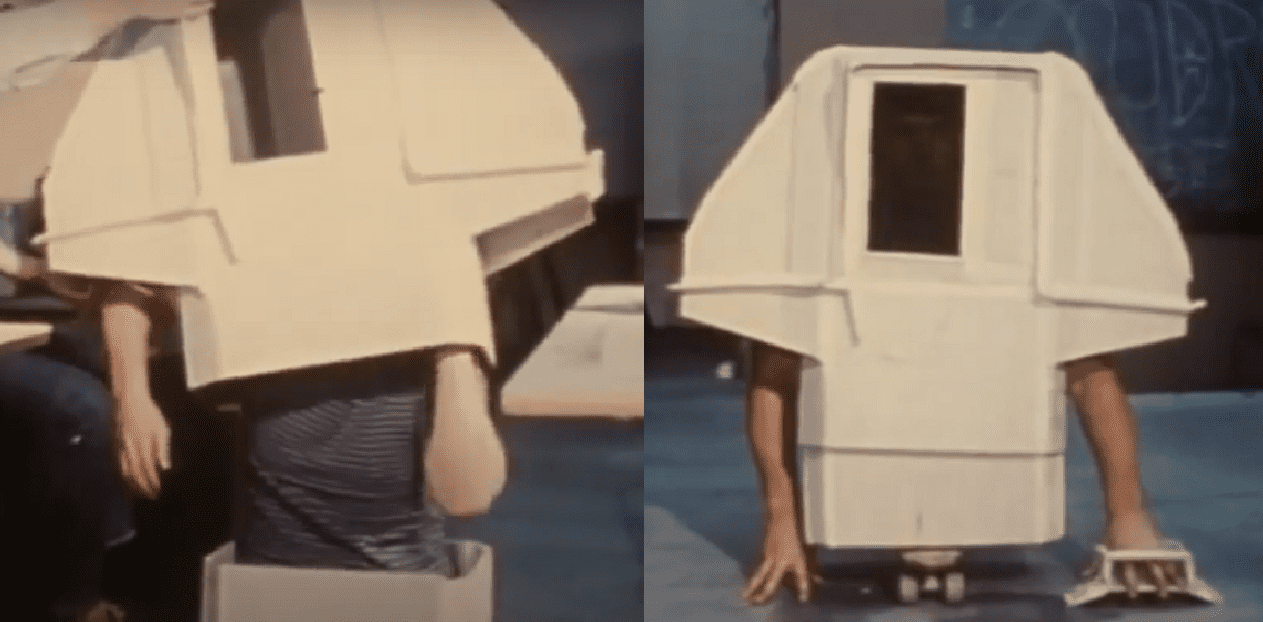

Mechanical drones in the film were a large part of the picture. The construction of the drones began with wood and vacuum-forming plastic over the frame. Each drone was built around the body of its inhabitant, who happened to be bilateral amputees. This unique choice would make it possible for the drones to be a very different visual from other mechanical characters in other films.

Paul Kraus, special effects technician in charge of the drone units, said this about the construction, “…the biggest structural problem that we found was that they had to be lightweight. We had to keep them under twenty pounds, which we did.”

The lightweight nature of the drones made it easier for the actors inside to move. It also meant the drones would be more than mechanical, they would have personality infused into them by the actors. Any heavier than twenty pounds and the drones would have been harder to move inside of, weighing down the movements, as well. As it was, each of the shots involving the drone’s manipulator arm were comprised of several takes due to difficulties with the mechanics.

For Silent Running, Trumbull had a great deal of freedom to produce the film. Like so many directors in the 70s, he assembled his own special effects team to create the look and feel for the film. This route for producing special effects would become the norm as the 70s progressed.

In 1973, the horror genre would produce a film heavy with visual and special effects. The Exorcist was based on William Blatty’s book by the same name. It featured effects so real and gruesome that it first had a rating of X. Because of its success, it surpassed The Godfather as the biggest money-maker of its time. It was also called one of the first blockbusters in film history, even before Jaws in 1975.

One of the first challenges for the film was the exorcism. To duplicate the novel, director William Friedkin wanted the room cold enough to see the actors’ breath. At a cost of over $50,000, a refrigeration system was installed. It was effective, as it lowered the temperature to twenty below zero. This was cold enough to form snow on one humid morning. However, because of the powerful set lighting, only three minutes of filming could be shot at a time. The exorcism scenes, as a result, took over a month to film since only five shots could be completed each day.

Lighting, itself, proved another challenge. Backlighting the actors was difficult because of the set-up of the room, its furnishings, and the angles at which the actors were shot. Friedkin did not want the film to contain “spooky lights” so all the lights in the bedroom had to come from a visible source. One of the more obvious challenges this presented was when the one lamp falls onto the floor. Since this changed the way the room would be lit, the lamp, itself, had to have its own special lighting. Friedkin also wanted the mood to change and be reflected in the lighting. To achieve his vision of “an ethereal quality,” the crew had to use bounce lighting.

Bounce lighting is achieved using a specialized reflector which redirects light at a specific subject.

Hiding the scene lights (not the set light sources such as set lamps) became difficult, as the room was so small and there were many people in front of and behind the camera. The crew used small incandescent bulb lights whenever they could find a place for them. These lights, called “inkies,” were controlled with dimmer switches. Wider apertures were necessary due to the lower light in most of the interiors. In addition, a gray taupe was used on the walls to give the impression of black and which. Toning the room in such a way made the priests’ robes stand out. It also meant that the only real color in the scene came from the skin tone of the actors.

The crew was given a full day to set up the lighting for the scene involving the arrival of Father Merrin. Because it had to evoke, in Friedkin’s words, “a melancholy traveler, frozen in time,” the crew used arc lights and tripod-mounted “troopers,” which boosted the brightness of existing streetlamps. After a full day, the scene was filmed the second night. The window frame had to be taken out of the façade and the spotlight shown between the window and its shaded frame. This was very difficult to do, and get the fog to roll in just right, in spite of a rather strong wind.

Marcel Vercoutere, special effects supervisor, built a life-sized animated dummy of the Regan character. It was made from latex and based on casts of Linda Blair’s body. Dick Smith, makeup artist, helped with making the dummy as realistic as possible. It included a condom along the throat so the area would bulge when speaking. It also had a tube which would produce clouds of vapor in the colder conditions. The dummy’s face could move and appear to speak and breathe. It was the dummy’s head which is seen rotating around on its shoulders, as the effect needed to be a practical one, not one which could be added in post-production.

Its realism was such, Linda Blair felt uncomfortable being around the dummy.

For some of the more controversial scenes, Blair had a stand-in. Actress Eileen Dietz, who also played the demonic entity, would be substituted for the crucifix scene and a lot of the scenes where the script called for tremendous amounts of profanity. Dietz and Friedkin argued a great deal over the scene and how to achieve what he wanted.

“He knew how to create an environment where horror actors would be at their best,” Dietz said.

Film and radio actress, Mercedes McCambridge also did some stand-in work for Blair, providing the voice for Regan, at times. The actress drank alcohol, breaking her sobriety, and smoked cigarettes to achieve the raspy, demonic voice.

In addition to the horrifying makeup applied to Blair, Dick Smith also had to age Max Von Sydow almost forty years to play Father Merrin. The actor spent almost four hours a day in the chair to achieve an older look. After The Exorcist, it was difficult for the actor to get roles because casting agents thought he was much older than his forty-four years.

Even though The Exorcist lost to The Sting, it was the first horror movie to be nominated for best picture in 1974. It would get a two Oscars for Best Writing and Best Sound.

Two years later, writer, William F. Nolan would have his novel, Logan’s Run turned into a film. Directed by Michael Anderson, it starred Michael York, Peter Ustinov, and Farrah Fawcett. Logan’s Run utilized holograms and the use of wide-angle lenses for its special effects.

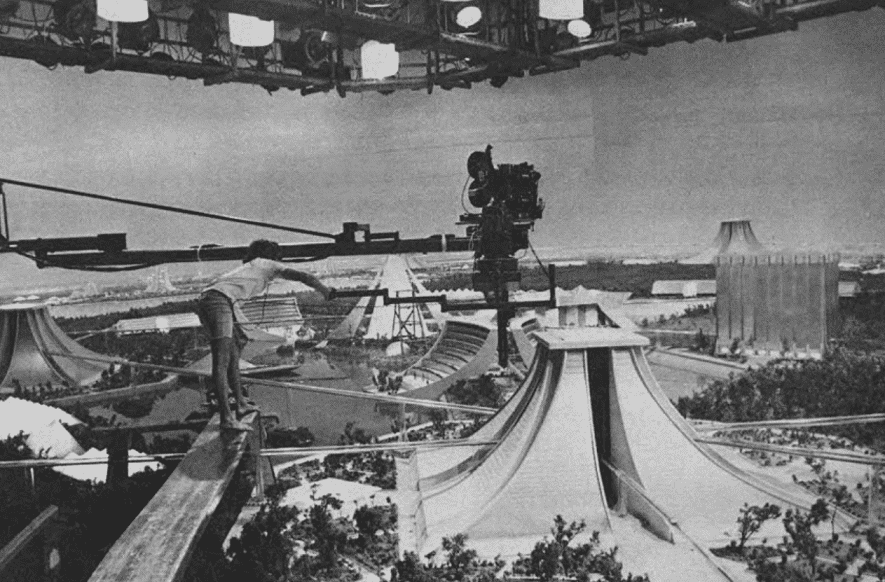

The Kenworth/Nettman Snorkel is a periscopic camera with a remote head, allowing for fluid movement in tight spaces where a normal camera might have difficulty. In the most basic terms, the Snorkel uses a periscope-like optical relay tube, extending downward and ending in a front-surfaced tilting mirror. The mirror’s size allows for closer shots and is equipped with pan, roll, zoom, and other functions. This camera was used in the film’s opening sequence where it pans down and skims over the lighted model of the film’s city.

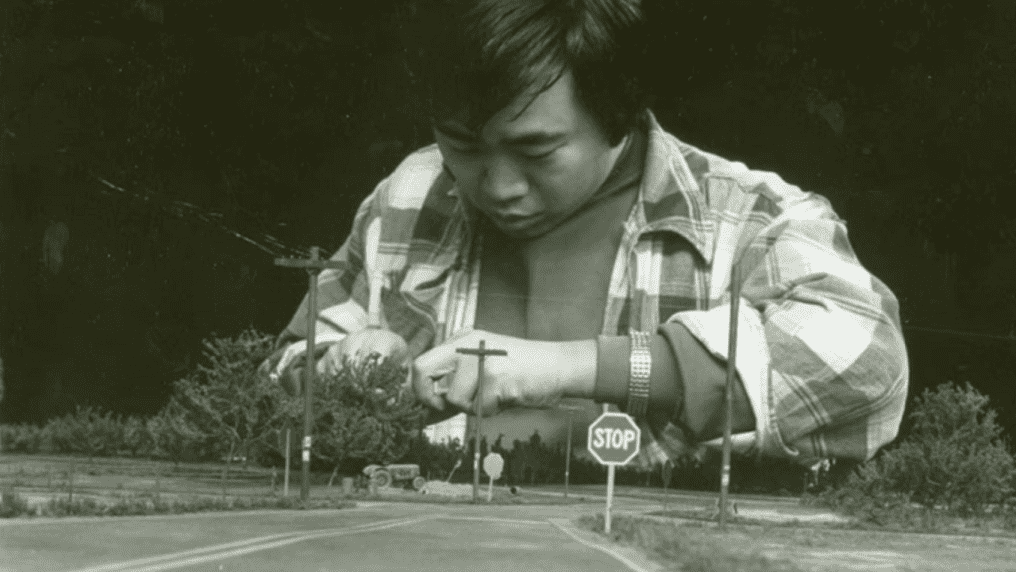

The interior and exterior pieces of the city were small-scale miniatures with the interior being about 1/48 size and the exterior being 1/400 full size. Moving parts were also miniatures with people being matted into the scene. In a few scenes, a color reversal internegative (CRI) process was used. Real people were filmed at the Sepulveda Dam, then “burned” into the shot. The technique is similar to older Harryhausen techniques using front-loading filming and painted mattes. These miniature scenes employed bluescreen technology so the end result could be cleaned up much faster.

To date, Logan’s Run boasted the largest miniature city ever built for a film. It was built on one of the nine Metro-Goldwin-Mayer sound stages reserved for the picture.

Special effects artist, L.B. Abbott worked with Glen Robinson on the creation of Carousel, one of the film’s central pieces. Several different cameras were set up to film every aspect of the giant, moving disc and the reaction of the actors to it. The area to be filmed in resembled an amphitheater with ascending seating. In addition to practical wire work, a company called Image West was employed to create computer images. While the work they did was not all-together useful for the scene, the idea for the action to be filmed right “off the tube,” led to an impressive force-field effect.

Ernest Laszlo, director of photography for Logan’s Run borrowed some special filters from Robert Wise, who used them for The Sound of Music. They were the only ones of their kind and Laszlo used them for his work on Fantastic Voyage. The effect in question was a type of crystal mounted in the ceiling. Participants in the Carousel would levitate up to this crystal, which seemed to sparkle. A star filter was used to achieve this sparkle. A star filter transforms hundreds of quartz light units, mounted onto a structure, into star-like points. Because the glow was quite brilliant, the filters Laszlo got from Wise were used to diffuse the light and help direct it. A bonus function of the filters was it helped hide the wires used to levitate the actors in the scene.

Logan’s Run won a Special Academy Award for visual effects and six Saturn Awards, including Best Science Fiction Film. A fourteen-episode series aired on CBS from 1977-1978.

Also in 1976, the film, Futureworld, would feature the first use of Computer-Generated Images (CGI) in a live-action film. The graphic was created by Triple I and was one of the earliest computer visual effects. This effect was a digitized rendering of character, Chuck Browning’s (played by Peter Fonda) hand and face. While brief, the rendering was effective and considered revolutionary.

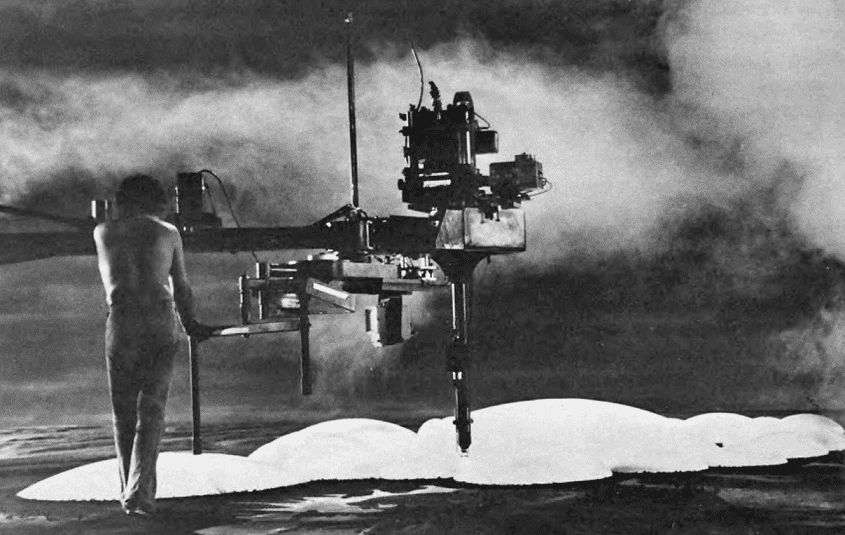

Director, Steven Spielberg, kept the special effects of his 1977 film, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, hidden for the majority of the picture. Douglas Trumbull served as the visual effects supervisor and Carlo Rambaldi designed all of the aliens. Close Encounters of the Third Kind has a visual effects budget of $3.3 million, one of the largest of its time.

The alien mother ship, designed by Ralph McQuarrie, was a four-hundred-pound model made from fiberglass. It stood four feet high and five feet wide. The whole of the ship’s interior was fitted with fiber optics, incandescent bulbs and neon tubes.

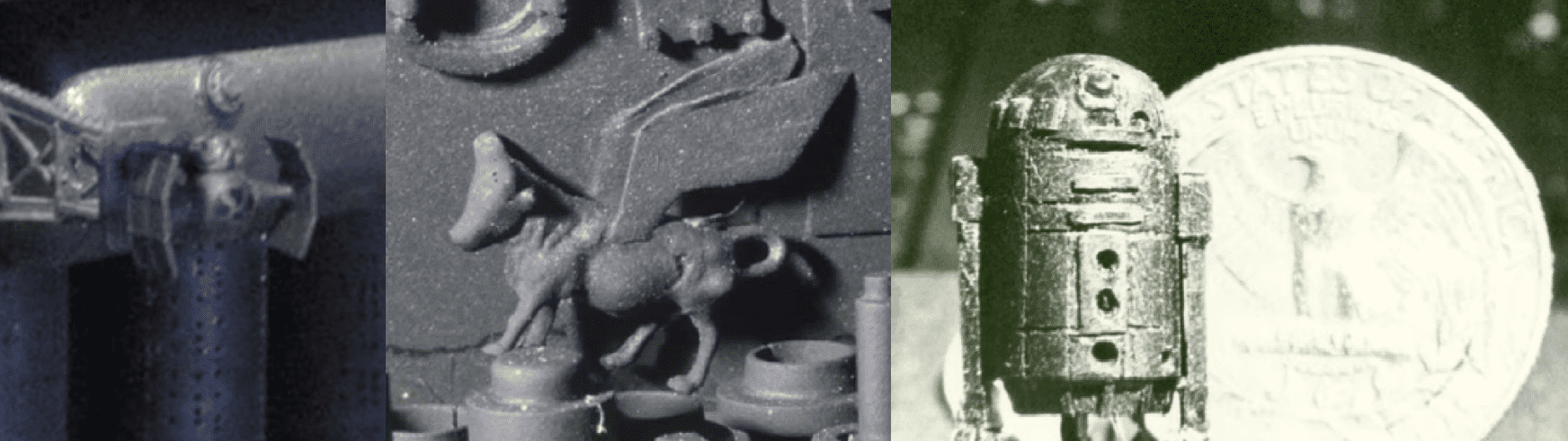

The mother ship would feature a lot of different pieces, but the crew also had quite a sense of humor about the things they added. Among them were a Pegasus, a shark, a graveyard, a mailbox, and a Volkswagen bus. Dave Jones, who worked on Star Wars: A New Hope, added in a TIE-fighter and an R2-D2 figure, no larger than a pea. The figure was then given its own LED light and backlit in the final shot. Aliens, mounted on small rods, were also added, even though most would never be seen. As with smaller miniatures, the mother ship was shot from a forced perspective to add to its size in the scene.

The original model is in the Smithsonian Institution’s Air and Space Museum Udvar-Hazy Annex.

The movie was shot on 35 mm film. The visual effects were shot on 70 mm film, giving them greater resolution than the rest. This meant, the visual and special effects would appear just as clear as the rest of the film. An optical printer was used to merge the two.

An interesting note about Close Encounters of the Third Kind is a test reel was produced using CGI. Spielberg did not like the look of the effects and thought the process would be too expensive and far too ineffective for what he wanted to achieve.

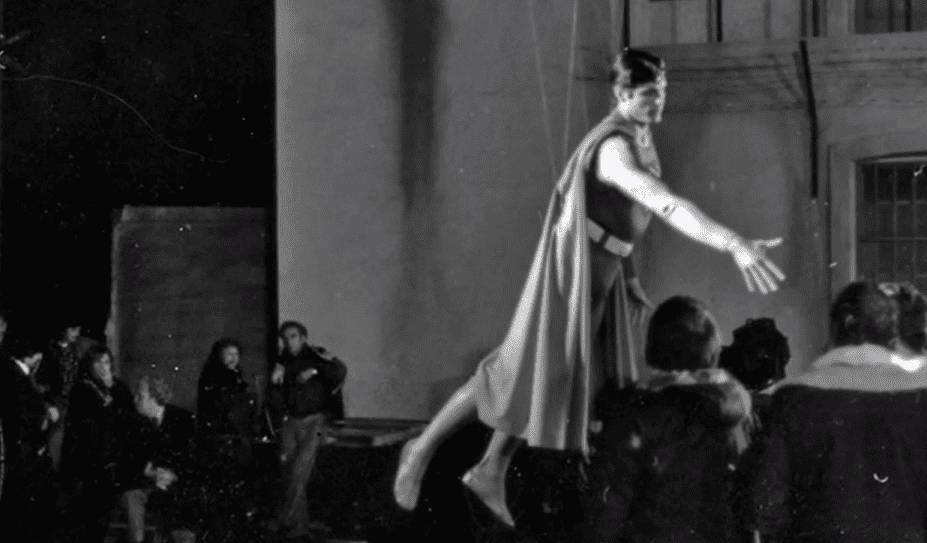

In 1978, another revolutionary film debuted. With the tagline, “You will believe a man can fly,” Superman: The Movie won the Academy Award for Special Achievement in Visual Effects. What set the film apart, from the beginning, was its animated title sequence, the first film with such a sequence. Animated words and pictures were generated by Douglas Trumbull, a familiar name in special effects of the time. Trumbull referred to the sequence effects as “streak” photography. The effect was achieved by moving the camera during the exposure of each frame of film. The camera’s motion was controlled by a computer but there was no CGI.

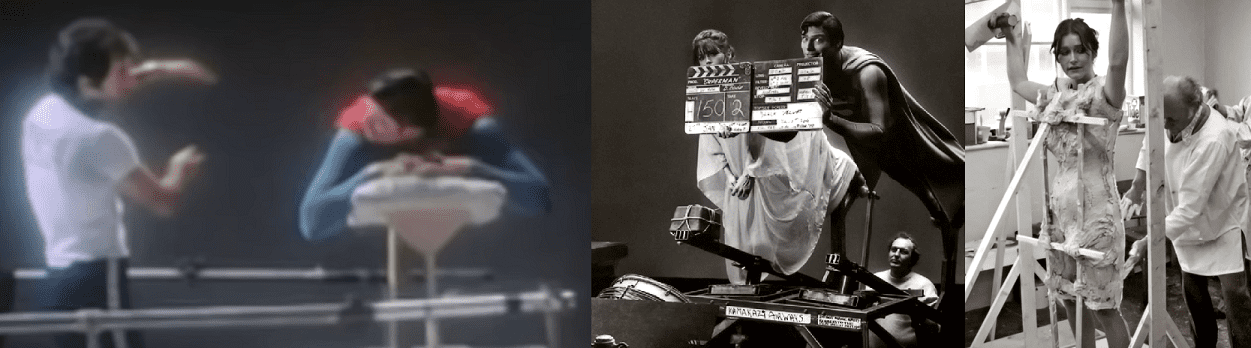

To achieve the film’s promise, several techniques were tested. One involved shooting a model out of an air canon. Another was using a radio-controlled flying model. Both of these lacked any kind of realism or control over the model’s movement. Wirework, by itself, would not allow for natural movement. Animation was also considered. While it gave the model control and movement, it lacked any kind of photorealism, which meant Superman just looked like a cartoon.

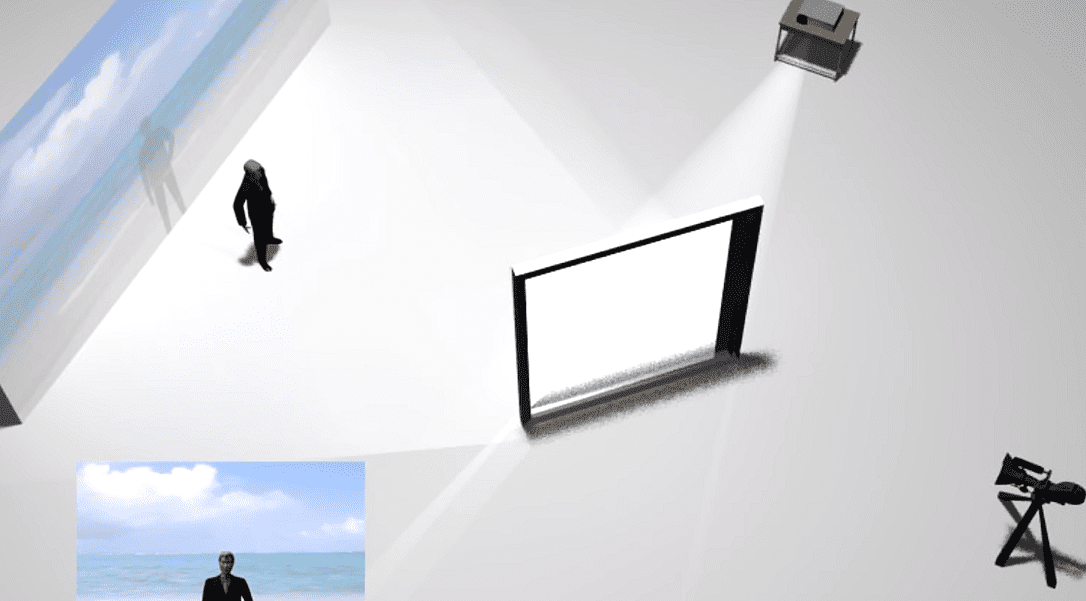

Fiberglass models were made of the actors’ bodies and mounted on hydraulic gimbals. Counterweighted arms were employed, as well. Front-screen photography was used for the non-static flying scenes, but a special camera had to be used. Superman: The Movie was the first film to employ the Zoptic camera for these shots.

A Zoptic camera is one utilizing front-projection. “Zoran Perisic patented a new refinement to front projection that involved placing a zoom lens on both the movie camera and projector. These zoom lenses are synchronized to zoom in and out simultaneously in the same direction.” (Wikipedia) What this means is, the image being filmed, and the image being projected appear to be unchanged through one camera lens. In Superman, it would allow for Christopher Reeve to be photographed against a moving background without the need for a lot of wire work. For any wire work Reeve was involved in, the wires had to be painted out.

The principal actors were photographed in front of a screen of M3 Scotch light. The screen was capable of reflecting light back at around one thousand times its original intensity. A projection, shot through a two-way mirror, would be displayed on the projection screen. Because of the high definition of the Zoptic camera and the projection, the actors were somewhat restricted in their movements. Cameras needed to be angled around the movement instead of the reverse.

The effect would also be used in the next two Superman sequels but not in the fourth because of budget restrictions.

Bluescreen technology was also used for Superman: The Movie. In order to get this to work, the costume department had to make the title character’s suit from turquoise material. This would allow the costume to stand out from the blue background. The screen was then removed by a photochemical process. The plate was color graded to restore the suit back to its original blue.

Colin Chilvers, who worked on 2001: A Space Odyssey, won an Oscar for his work on Superman: The Movie. He worked on Superman II and Superman III.

Toward the close of the 1970s, other films would also revolutionize the special effects industry.

1979’s The Muppet Movie featured some of the most advanced and complex puppetry of its time. For the opening sequence, alone, puppeteer, Jim Henson spent an entire day in a fifty-gallon steel drum, submerged in a pond. In one of the latter scenes of the film, Kermit rides a bicycle without any visible means of him doing so.

Innovations of all sorts came about in the 1970s. None would be as industry-changing as a film by George Lucas in 1977.