“I didn’t steal Alien from anybody.” O’Bannon is credited as saying. “I stole it from everybody!”

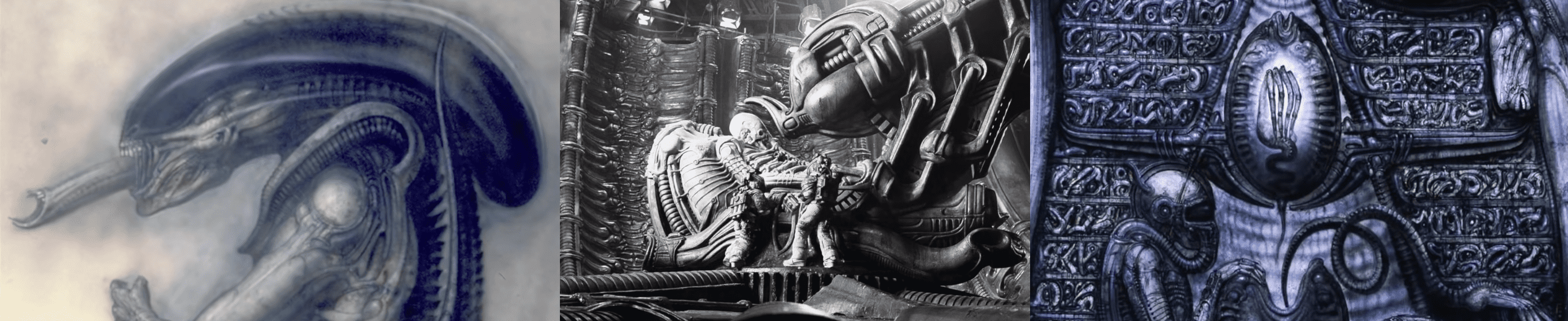

In 1979, movie-going audiences were introduced to Alien, a science fiction horror film directed by Ridley Scott and written by Dan O’Bannon. The film was based on a short story by O’Bannon and Ronald Shusett. Ron Cobb and Chris Foss, both concept artists, designed most of the more human elements and Swiss artist, H.R. Giger designed the alien and its surroundings.

When asked about his inspiration, O’Bannon cited The Thing From Another World, Forbidden Planet, Planet of the Vampires, and a short story by Clifford D. Simak and one by Philip José Farmer called Strange Relations.

O’Bannon was influenced by Foss and Jean “Moebius” Geraud, having been introduced to their work while in Paris working on Alejandro Jodorowsky’s adaptation of Dune. The project collapsed and O’Bannon returned to Los Angeles where he began working on a project with Shusett. The working title for the project was Star Beast but because of how many times the word, alien, appeared in the writing, he changed the name to Alien. The title’s simplicity and versatility as both a noun and a descriptor, caused the title to stay.

Because Alien was the only script on the desks of 20th Century Fox after the release of Star Wars in 1977, Alien was put into production with a beginning budget of $4.2 million. After a few other directors passed on the project, Ridley Scott accepted and created elaborate, detailed storyboards for his version of the script. He drew on movies like 2001: A Space Odyssey, Star Wars, and even The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, in reference to the horror aspect.

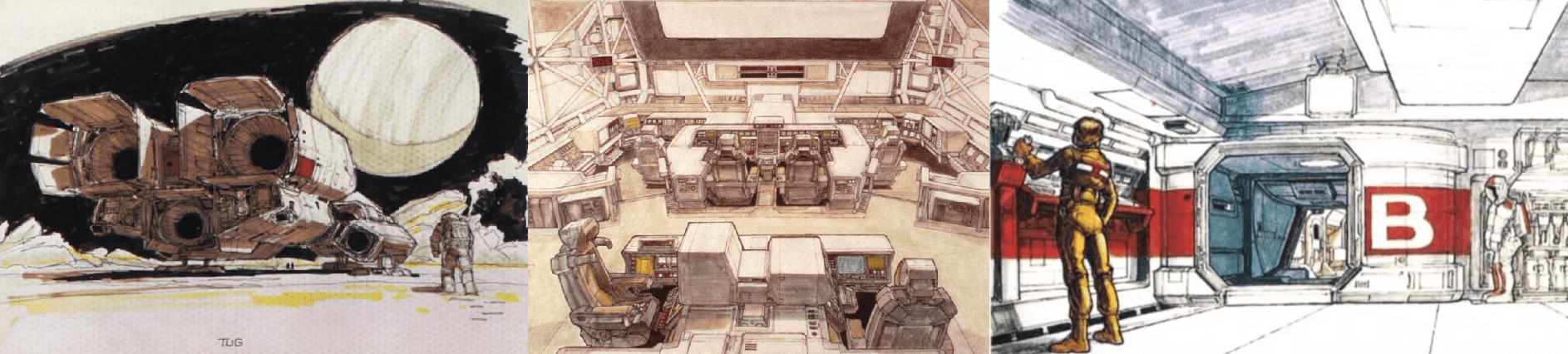

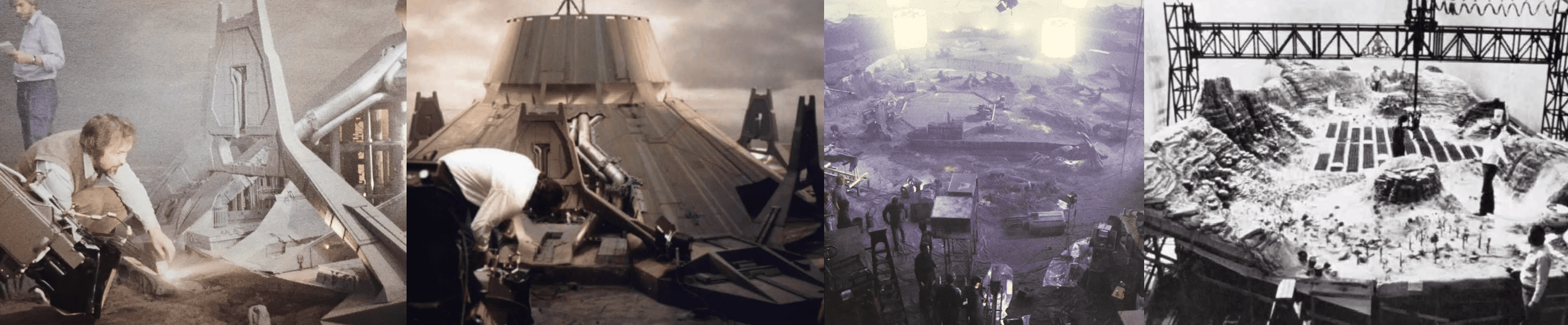

Filming began in 1978 in Shepperton Studios, near London. A crew of over two hundred constructed the main sets of the alien planetoid and the interiors of the derelict spacecraft and the Nostromo. Each deck of the ship occupied a separate stage. Connecting hallways, the only means of access for the actors, gave the sets a sense of realism. Throughout the sets, the name Weylan-Yutani appears. This comes from the British Leyland Motor Corporation and Ron Cobb’s Japanese neighbor. In the sequel, this would be changed to Weyland-Yutani.

Roger Christian, the film’s art director, worked on Star Wars. As a result of his experience, he used scrap metal and other parts to construct the sets. This approach gave them a used, industrial feel. To save money, mirrors were often used along the corridors to make them appear longer than they were.

O’Bannon had been introduced to the work of H.R. Giger alongside Foss and Moebius. Art director, Les Dilley, created his scale models and the planetoid’s surface based on Giger’s work, as well. The influence of the Swiss artist would be pervasive. Moebius’ costume renderings were the inspiration for the final space suits created by costume designer, John Mollo.

O’Bannon said, of Giger’s work, “His paintings had a profound effect on me. I had never seen anything that was quite as horrible and at the same time as beautiful as his work. And so, I ended up writing a script about a Giger monster.”

After being introduced to Giger’s work, Scott flew to Zürich to meet with the artist.

Hans Ruedi Giger was a Swiss artist known for his “biomechanical” art style which often merged human physiques with machines. He was brought onto the visual effects team because of his influence in the original short story and the subsequent designs. His design for the creature was inspired by his painting, Necronom IV. He earned an Oscar for the creature in 1980.

In direct contrast to the industrial feel of the Nostromo, Giger designed the alien portions to appear organic. For instance, the egg chamber included dried bones and plaster to sculpt some of the scenery and its other elements. What the crew referred to as the “space jockey” contained only one wall, which Giger airbrushed by hand. The “jockey” was placed on a rotating disc, which could be rotated for the appropriate shots.

To get a sense of scale for the live-action shots of the Nostromo, a fifty-eight-foot landing leg was built for the exterior shots. To enforce the illusion, Scott’s two sons and the son of the movie’s cinematographer were used as stand-ins for wide shots. This was also done when the crew encounter the dead alien in the derelict craft.

While it was available to them, the special effects crew chose not to use motion-control filming. Time constraints prevented stop-motion work so this would have been a waste of time and effort. This made it possible for the team to focus all their attention on regular models and wide camera shots.

To achieve the shot of the Nostromo landing, Ridley Scott used a regular camera and shot the sequence, himself. Smoke was added to give ambience to the planet. He used tight, close-up shots of the ship to avoid having to have stars in the background. This was how he achieved movement in what would have been a static shot.

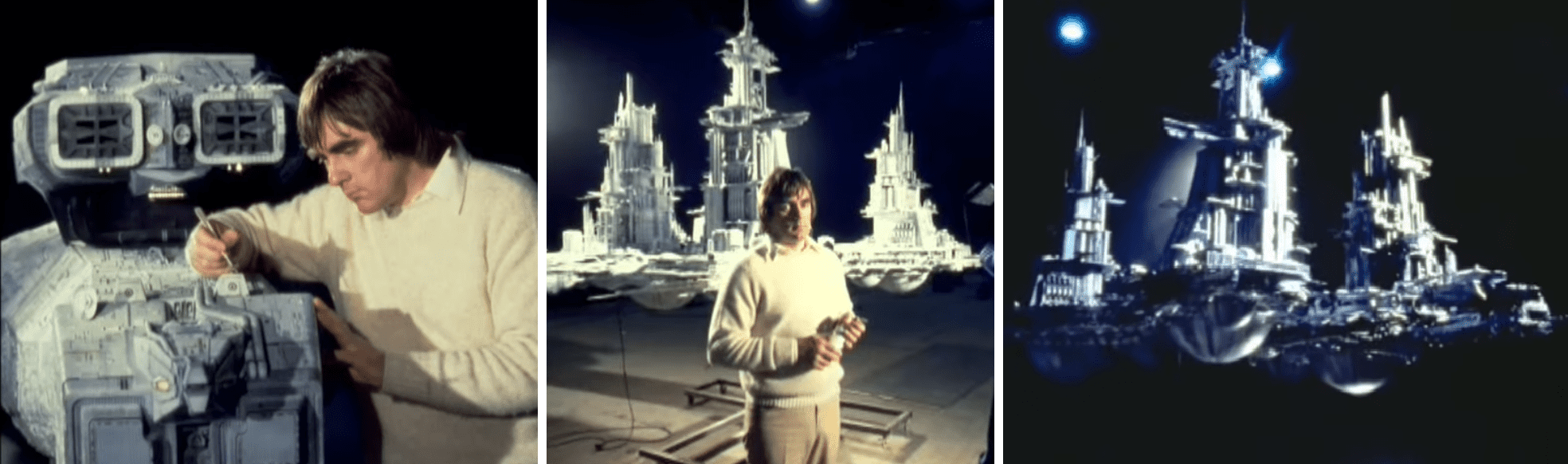

Brian Johnson started as the visual effects supervisor for the film. “When you’ve got somebody like Ridley, who’s very precise about what he wants,” Johnson said. “He doesn’t go from one thing to another, he just expands and expands and expands.”

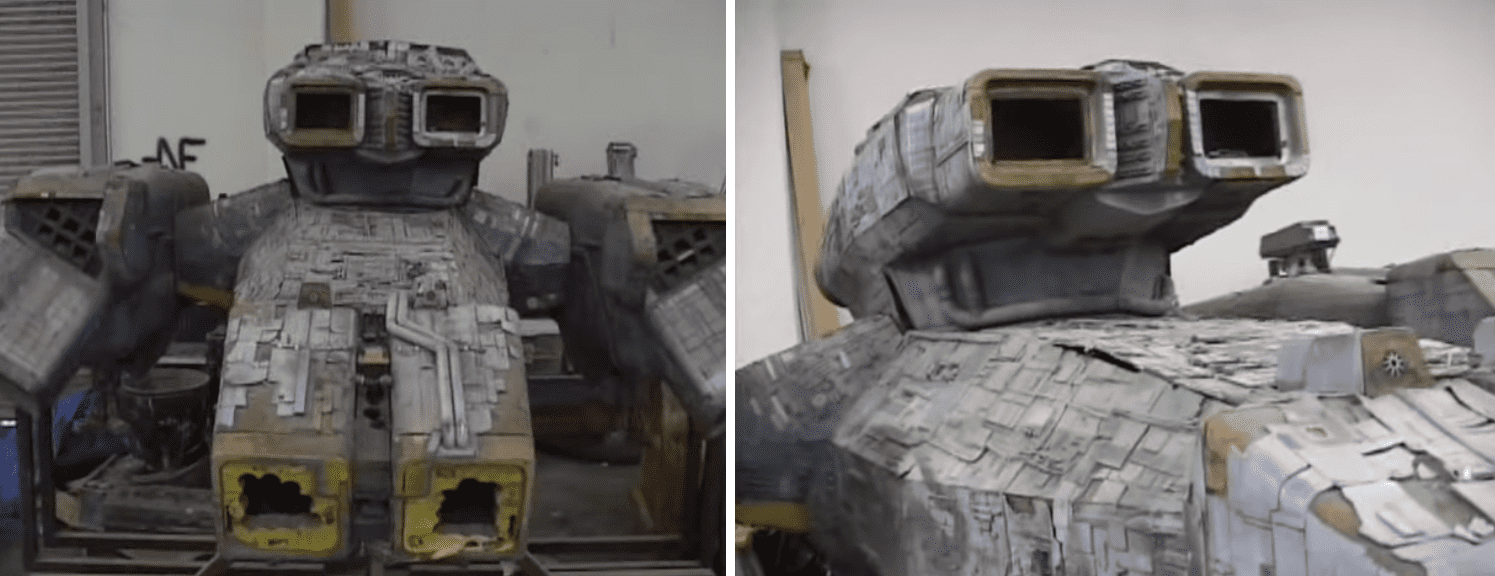

An example of this expansion was the model for the Nostromo. It started at ten to twelve feet and grew to over sixteen feet long because Scott continued to add things onto it. Over one hundred and fifty model kits were used to build the ship. It weighed so much because it had a metal frame. It had to be moved with a forklift. In the scene where the ship pulls away from the refinery, the effects team covered the forklift in black velvet for filming. Wind machines, smoke, and lighting added nuance and movement.

A separate, forty-feet model was created for the underside shots where Kane’s body would be jettisoned and later, when the shuttlecraft, Narcissus detached. Wide-angle lenses on a mounted camera filmed these shots. A twelve-inch model was used for medium and long shots while a four-foot model was used for rear shots.

For fans of Alien, there is a scene in Blade Runner where the crampon is shown on a screen. This is followed by the word, “Purge.”

Martin Bower, supervising model maker, worked on Space: 1999. He worked with Nick Allder, who replaced Johnson as special effects director when Johnson went to work on The Empire Strikes Back. Bower made an interesting observation about the move away from practical effects to computer generated imaging.

“CGI has probably, in my personal opinion, as a model maker, decimated much of the model-making,” Bower said. “I don’t think, myself, that CGI will ever completely replace models. I don’t care what anyone says, I think you can tell.”

To sort of echo this, Brian Johnson said, “…because the script was so beautifully written, and because Ridley was really clever with the way we didn’t see the alien, we were just there to remind people that there was a bit of space outside and that they were billions of miles from anywhere. It didn’t have to be a visual effects extravaganza, as such, to save a movie.”

One of the more groundbreaking computer effects for the film came when the Nostromo is landing. A wireframe 3D graphic for the ship’s computerized navigational charts shows mountainous terrain on the planetoid. This kind of wireframe, computerized graphic was new, for its time, and impressed audiences. In spite of its dated, 1970s-80s technology, the graphic does not stand out in the film as anything of the sort. It fits the look and feel of the technology presented in the film.

Johnson went on to add, “We just enhanced what was already there, as opposed to some other movies which are visual effects tour de forces but no story. The key to this was the amazing story.”

An often overlooked special effect was the film’s opening sequence. Developed by R/Greenberg Associates, the broken letters and the spacing in between them was meant to unsettle the audience, to make them feel a strange sense of foreboding. According to Oliver Lyttelton’s, The 50 Best Opening Credit Sequences of All Time, the title sequence for Alien is one of the most iconic of all time.

The introduction of the movie’s antagonist begins in its first form. The egg was constructed from fiberglass, which would allow the audience to see movement inside it. Scott’s own hand was used for these scenes. The egg, itself, was made from a cow’s stomach and tripe, with the top of it being hydraulic. Initial designs called for the outer portion of the thing to have a single slit but production thought this to be too sexual, so the design was changed.

For the next stage, a sheep’s intestine was used for the “facehugger’s” proboscis. This form was fired from the egg with a high-pressure air hose. The final piece of footage was slowed down and reversed to “prolong the effect and reveal more detail.” (Wikipedia) Giger designed this version of the creature first, after many different versions varying in size and scale.

O’Bannon and Cobb drew their own version based on Giger’s designs. For this version, Scott used pieces of fish and shellfish for the scene where the dead creature is examined.

Its incubated form was inspired by Francis Bacon’s 1944 painting, Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion. The painting is a triptych with the canvases depicting three grayish-white creatures against a burnt orange background. The depictions are a combination of Picasso’s biomorphs, his interpretations of the crucifixion of Christ, and the Greek Furies. To give some significance to this influence, this painting is considered one of the artist’s most realized and mature.

One of Alien‘s most memorable scenes of the creature, in this form used a combination of hand puppets and external tubing. While a single hand puppet of the creature shot out of the chest cavity, fake blood was forced through the tubes. Wires were used to make the creature move once it was free of the crewman’s chest. The scene was shot in one take with the reactions of the unsuspecting cast being genuine.

Tom Skerritt said, of Veronica Cartwright’s reaction, “What you saw on camera was the real response. She had no idea what the hell happened.”

Giger’s design for the adult creature was sculpted by the artist using plasticine. He incorporated snake vertebrae and cooling tubes from a Rolls-Royce. The head was made by Carlo Rambaldi, who worked on Close Encounters of the Third Kind. The only modifications in Giger’s design came from the parts which would allow for animation of the jaw and inner mouth. Hinges and cables made this feature possible. The upper portion of a human skull was utilized for part of the creature’s face.

K-Y Jelly was used for the creature’s saliva.

Discovered in a pub by a member of the casting team, Bolaji Bodejo played the title creature. Standing six feet, ten inches, a full-body plaster cast made it possible for the suit to be an accurate fit. The actor took tai chi and miming classes to give the creature the sort of menacing grace Scott wanted. In tighter shots where safety was the first priority, stuntmen Eddie Powell and Roy Scammell portrayed the creature. One such time was when the creature lowers itself from the ceiling. Powell was suspended on wires and lowered as he unfolded his body.

What gave this approach a decided edge was the fact, the audience never knew what the creature was going to look like when they saw it next. This heightened anticipation and fear in test audiences.

A face cast of actor, Ian Holm was made for the scene in which his character is decapitated, and its head placed on a table. The latex shrank during its curing stage and was unconvincing. Instead of the cast, Holm knelt under a table with his head coming up through a hole. To make the character’s insides, a combination of pasta, fiber optics, caviar, and Foley urinary catheters were used. The liquid coming out of Holm’s mouth is milk.

Alien won the Oscar for Best Achievement in Visual Effects in 1979. The movie also won three Saturn Awards (Best Science Fiction Film, Best Direction, and Best Supporting Actress for Veronica Cartwright) and a Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation.