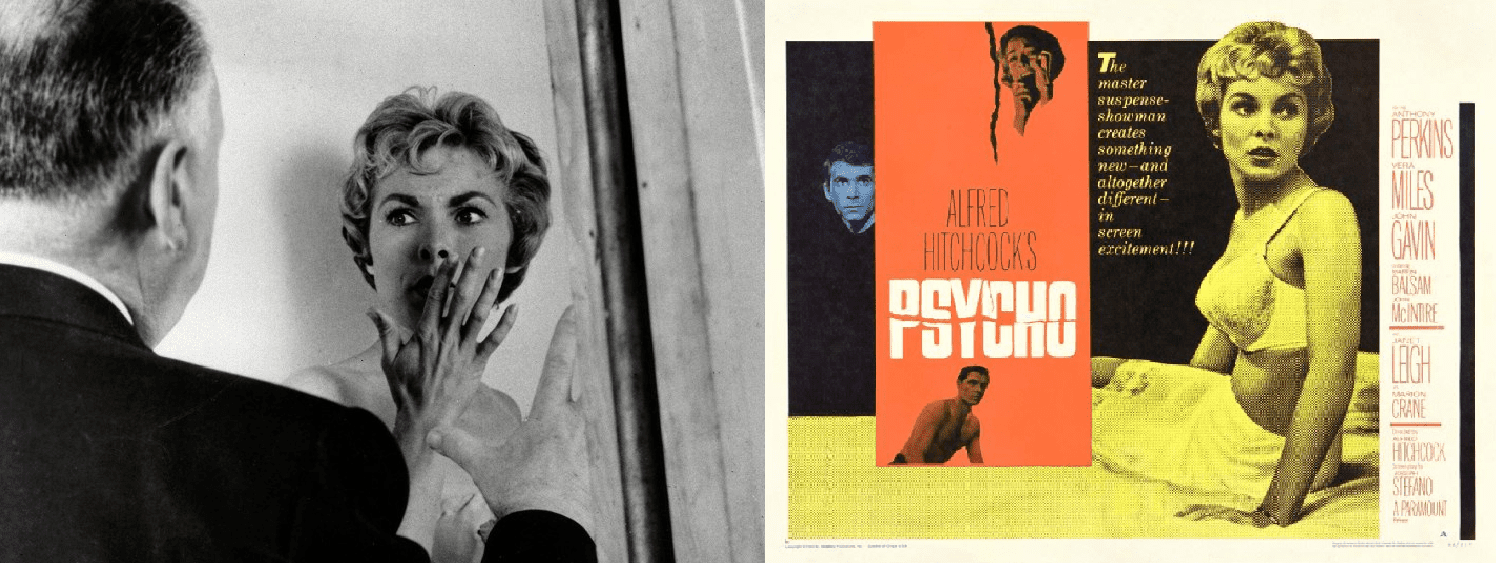

Special effects of the 1960s relied on technical skill and a degree of believability. One example of this was the shower scene in Pyscho. Because of over-imitation in pop culture, the scene has lost a lot of its artistic feel but the technical aspect makes it an enduring standout.

Storyboard artist, Saul Bass drew out every shot of the sequence and Hitchcock directed it. The pivotal scene of this low-budget film took almost a week to shoot and was comprised of over seventy camera set-ups and fifty different shots.

A long lens was used in the initial capture-shot. To avoid splashing the camera, some of the showerhead holes were plugged and the camera placed several feet away. Blood, for the scene, was Hershey’s chocolate syrup, because of its thicker density and color. It showed up better on black and white film. Sound effects for the knife attack were made by plunging an actual knife into a casaba melon. The knife was not shown penetrating the skin, as some might believe. Instead, a bit of blood had been added to the tip of the knife, which was positioned against Janet Leigh’s navel, then brought back. The scene, shot in reverse, is often used to show some imagined violence.

“No, you didn’t see this. You thought you did but you didn’t,” Hitchcock said, regarding the movie’s censors. “I didn’t do the things you told me not to do. I was a good boy.”

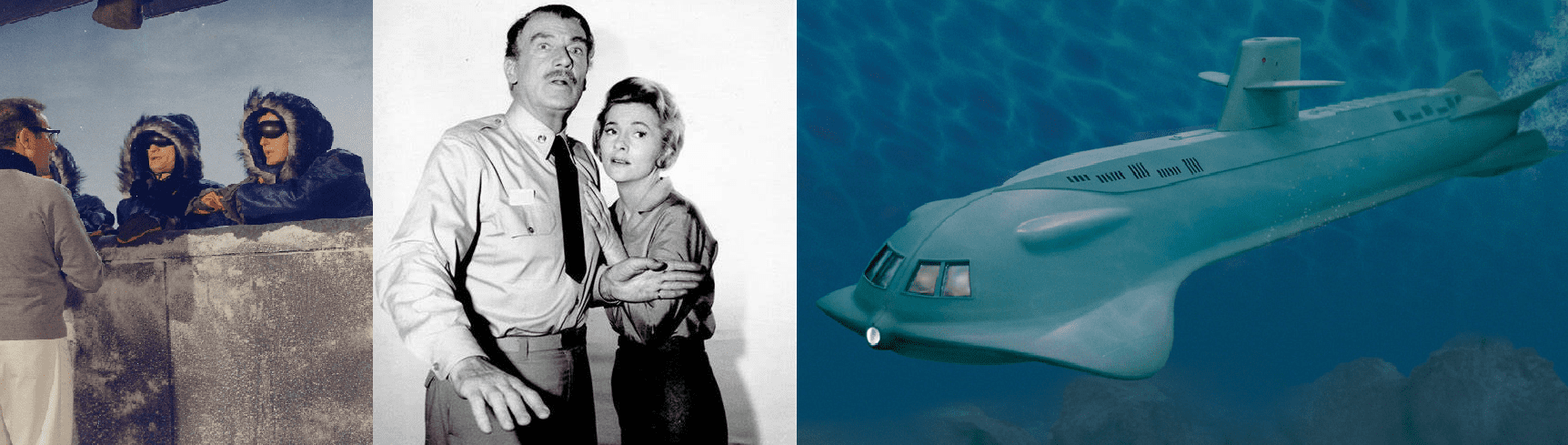

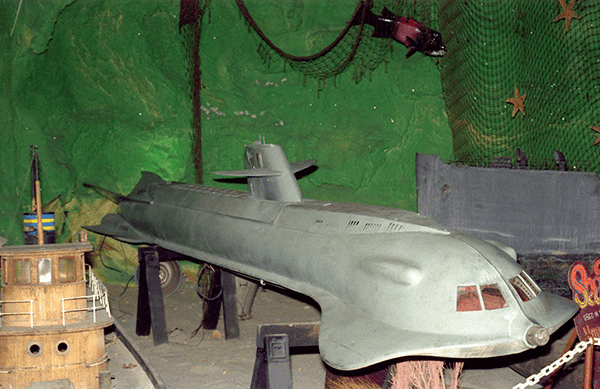

In 1961, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea employed a variety of methods to achieve its special effects. The first, most reliable method was the use of models. The Seaview was recreated in different miniature forms ranging from one to two feet all the way to the eighteen-foot model. The model were filmed at different speeds to achieve the different effects of the scene.

L.B. Abbott, who served as the film’s visual effects technician, said, “There is an empirical rule governing the camera speeds used for various scale miniatures. The rule is, the camera speed should be the square root of the miniature scale.”

This unofficial rule meant, the eighteen foot Seaview model would be filmed at one hundred, thirty-six frames per second so that the playback gave the illusion that the surrounding waves were bigger than they were. Large fans agitated the surface of the water and wave generators in the pond intensified the effect. A small amount of detergent was added to help create the effect of water turbulence.

An eight-foot model of the Seaview was used for the undersea sequences. This was filmed on the 20th Century Fox lot in a large tank measuring sixty feet square and eleven feet deep. A special camera, mounted in an open-top diving bell, was used to shoot the scenes. It was equipped with a convex glass port, which cut down on the refraction of the water, which could magnify some of the models. The cameras would also be fitted with the CinemaScope lenses so the convex glass helped with the field of depth for the scenes, as well. This was important since the special lenses lacked depth.

Scenes involving the giant squid were also filmed in this tank. The squid is an example of a mechanical effect, one in which a large device is built to scale so the actors can interact better with it. The mechanical squid looked good in publicity pictures. Budget restrictions on Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea meant the device was very limited and lacked a lot of the movement necessary to make its scenes realistic. As a result, much of the fight scene had to be put together in the editing process.

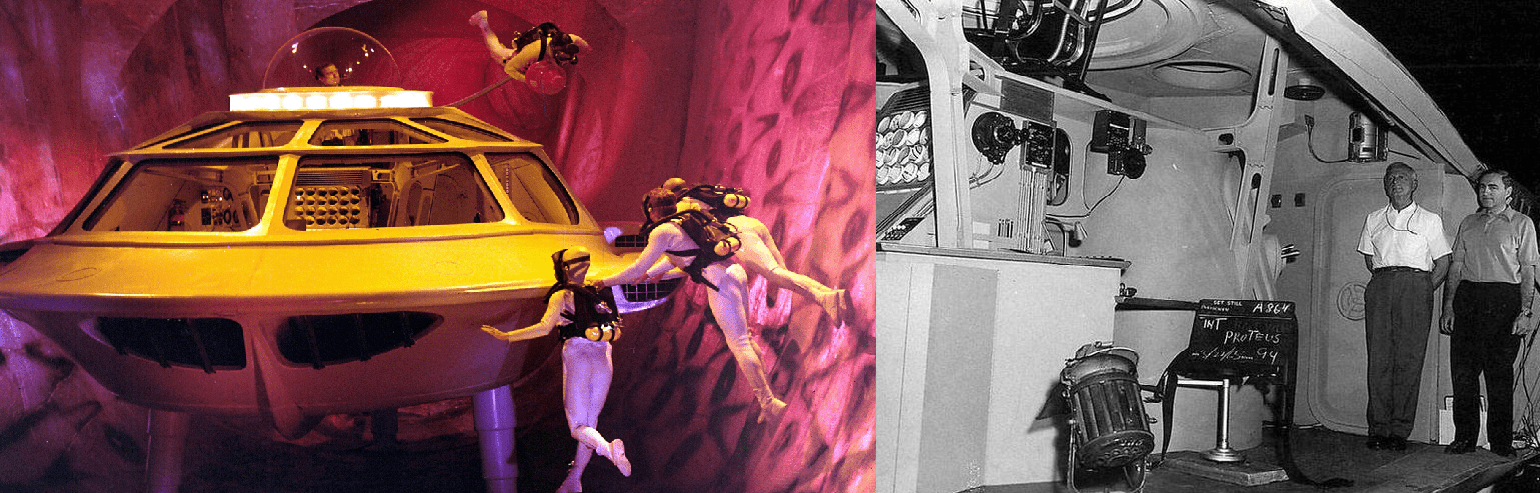

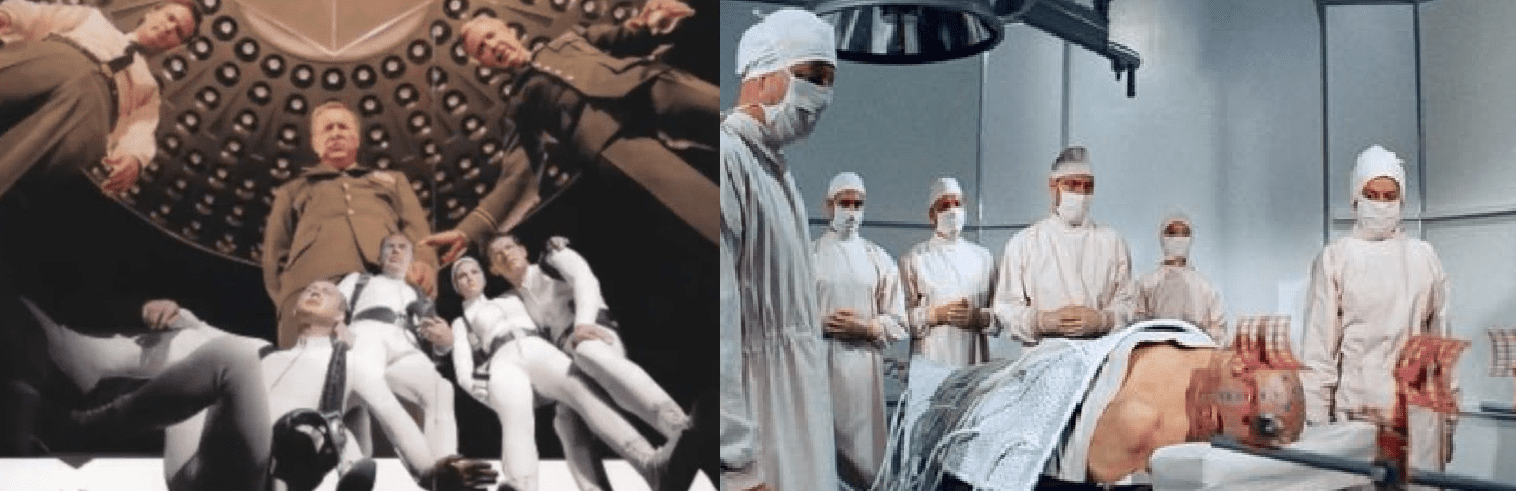

The 60s saw a rise in science fiction. Fantastic Voyage, based on a story by Otto Klement and Jerome Bixby, capitalized on this rise in 1966. With a budget of $5 million to begin with, its finishing budget of $6 million was divided into $1 million for test footage and $3 million for sets.

The Proteus submarine set was built to be forty-two feet long. It contained all of the interior sets, which could be pulled out to allow for cameras and crew. This same set was also built in miniature around five feet in length. Sets of the internal organs were built around the five foot model on the Fox soundstage. Blood cells and other internal pieces were filmed by themselves and composited into the film. An eighteen inch Proteus was built for scenes in which it would move through the arterial wall. An even smaller version was constructed for the injection scene. To achieve the plasma effect, they used multicolored lights outside the translucent pieces.

Richard Edlund, Visual Effects supervisor for the film, says the technical aspects were “murderously difficult.” The reference being the scene in which the Proteus is miniaturized. This was achieved by putting a stationary camera at a particular angle, then dollied back as it filmed the miniature on a blue screen. Matting was also used, as were cut-shots which allowed for the passages of crucial seconds.

Peter Foy was the technical advisor for the film’s flying sequences. These sequences refer to the portions where the crew moves through the body. This was done by putting the actors on wires and moving them through the scaled sets. In the 60s, the technology did not exist to go into the film and remove the wires so the scenes had to be shot in a way which hid the majority of them. For the continuity shots, the wires could be blurred by the overlays and matting.

What set Fantastic Voyage apart, in terms of effects, was the fact that everything in the film had to be photographed in a literal sense. This meant everything you see had to be constructed. Nothing was cheated by using a computer. One of the scenes in which a character died had to use realistic substances and a small bit of animation for the finished product. The blend of the two did not overwhelm the scene.

The sound effects for the film’s opening, called Hickey Effects, were created by Ralph Hickey. Their original use was for a comedy starring Spencer Tracey and Katherine Hepburn called Desk Set. They were used in later Irwin Allen television shows and have become synonymous with science-fiction sounds of the 70s and early 80s.

Fantastic Voyage won the Oscar award for Visual Effects in 1967.

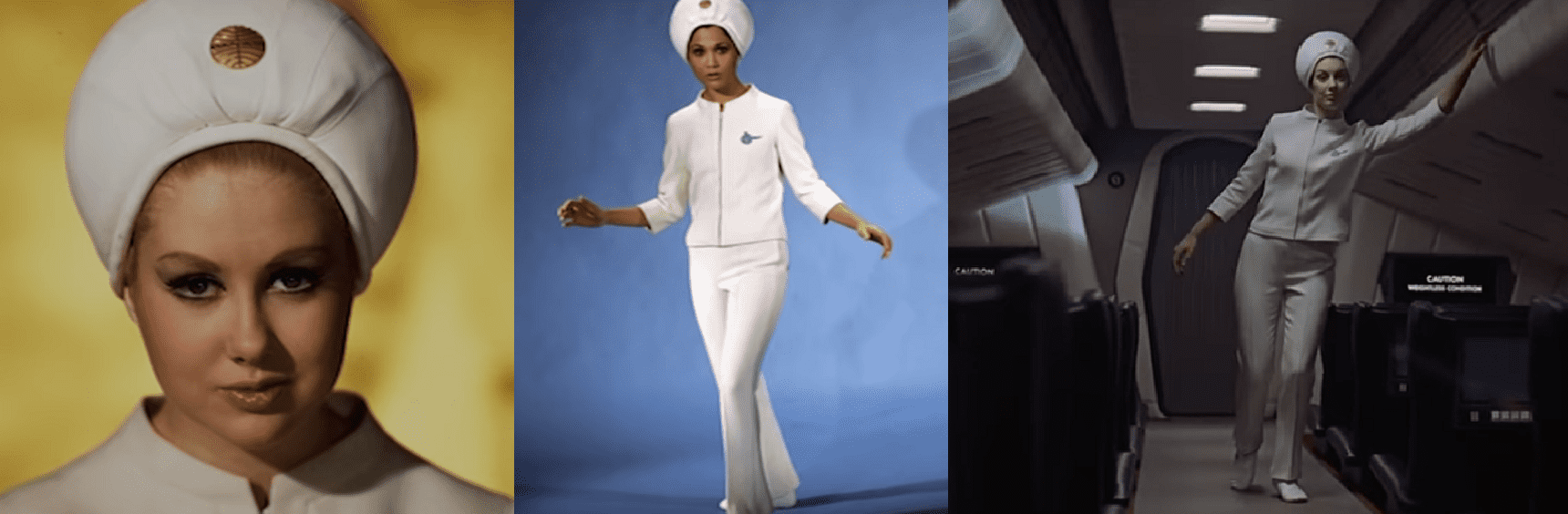

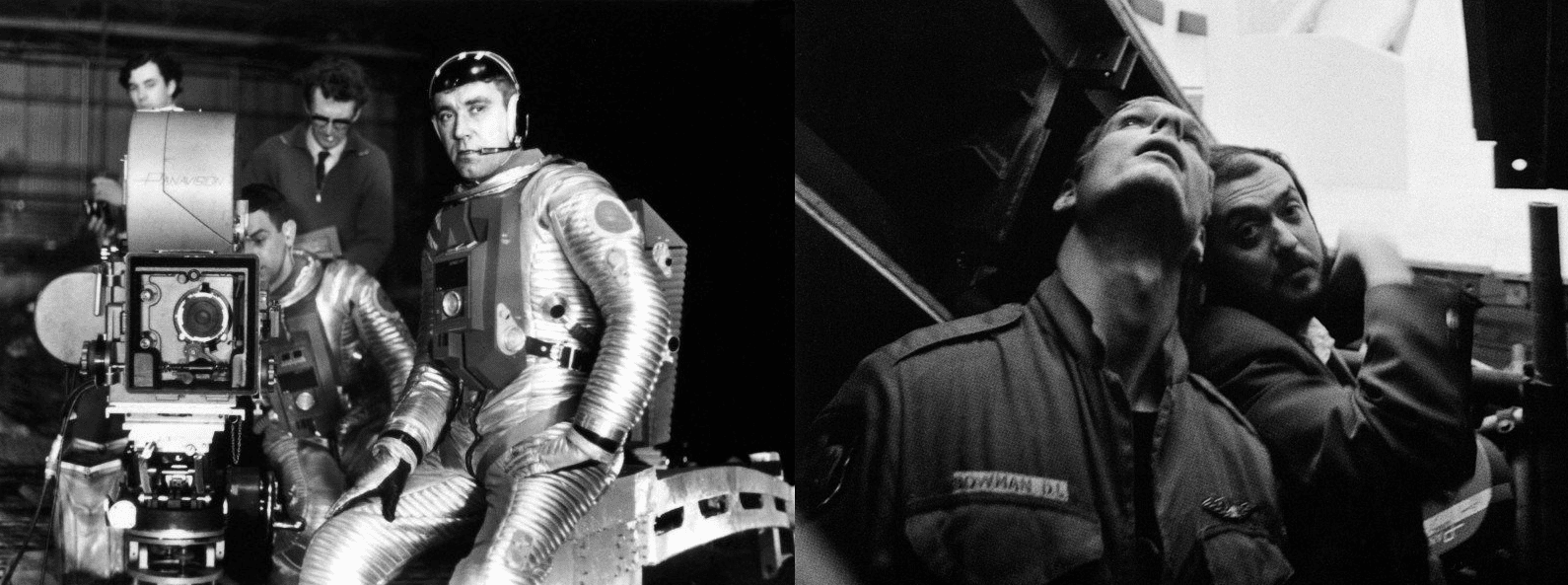

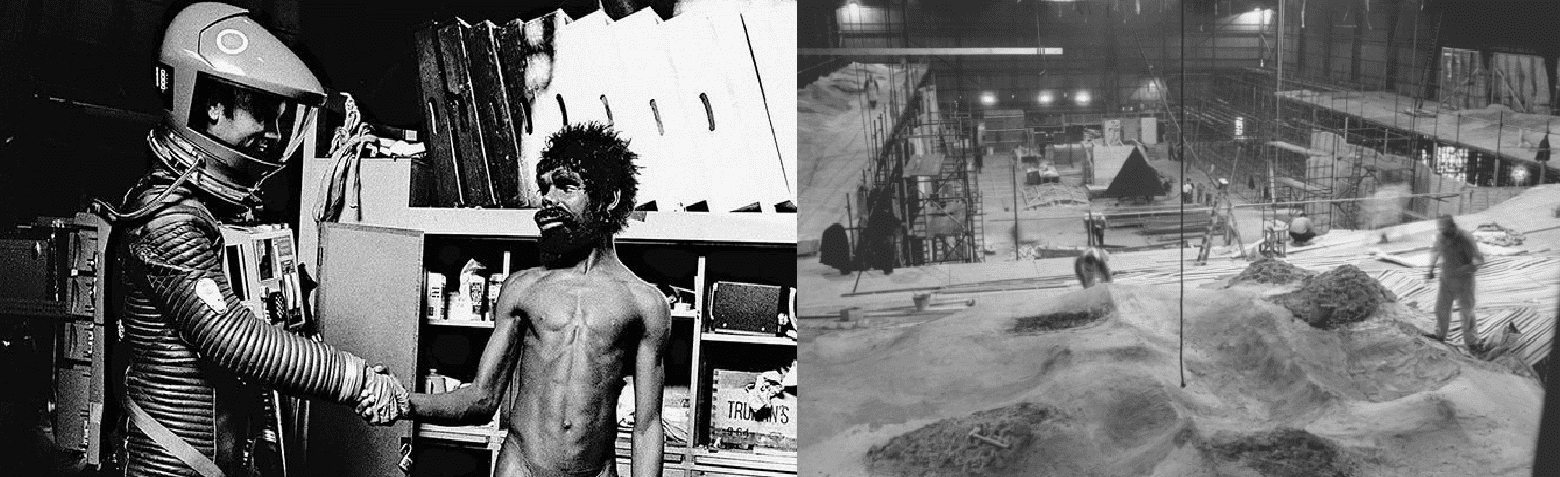

Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey is called a “visual-effects pioneer.” For 1968, the idea of a rotating movie set was very new. Vickers Armstrong was commissioned by Kubrick to build a centrifuge that was thirty-six feet in diameter and cost seven hundred and fifty thousand dollars. Scenes involving the living quarters were filmed inside the centrifuge. Actors in the scene had to be very precise in their movements or they might fall over during filming. The centrifuge moved the entire time. The scene involving the stewardess walking up the wall utilized two simultaneous shots being superimposed upon one another. While the actress walked a treadmill in the back, the foreground centrifuge moved and a stationary camera, locked into place, filmed both actions.

You might recall this same effect being used in 1982 for the film Poltergeist, where Jo Beth Williams moves around the ceiling, or in 1984’s Nightmare on Elm Street where the same thing happens with Amanda Wyss. The effect has been duplicated in a number of films.

The pop band, N’Sync even used this technique in their Bye, Bye, Bye video.

Another visual distinction 2001: A Space Odyssey had was the way its space vehicles moved throughout their scenes. This kind of motion control was achieved by setting up cameras on mechanical rigs which were automated to capture different angles at different times, and at different speeds. The various shots were then edited together to give the same vehicles very different movements.

The most obvious film to duplicate this technique is Star Wars: A New Hope where the various attack ships descend on the Death Star in the film’s climax sequence.

One of the more impressive techniques is the slit-scan. This was invented by John Whitney and used in the 1958 Hitchcock film, Vertigo. Douglas Trumbull adapted the slit-scan to fit the feel of Kubrick’s film. This effect is achieved by having the camera focus and film on a narrow slit in a screen. Images used would be moved back and forth behind the screen while the camera films in long-exposure.

The elongated effect would be used in the title sequence of 1973’s Dr. Who and the “warping” effect of the Enterprise in the opening of Star Trek: The Next Generation.

An excellent, more in-depth explanation of the slit-scan can be seen here:

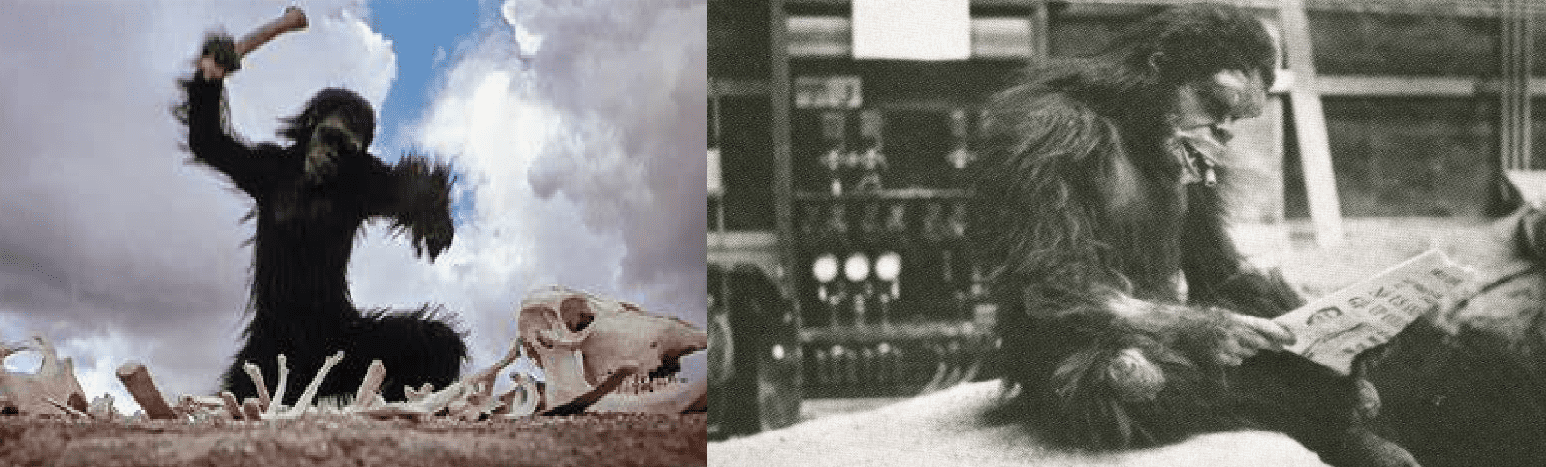

Front projection was another innovation of 2001: A Space Odyssey. A single image is projected onto a two-way mirror. The image is reflected onto a screen made of scotch light, a reflective material used to make movie screens. More modern front projection utilized blue and green screen to make certain extraneous elements can be edited out. For this film, plate glass scenes were shot in Africa. They were made into eight by ten Ectochrome transparencies, then projected onto a forty by ninety foot scotch light screen. Large-scale front projection like this had never been done before. The angle of the principle filming camera would hide any shadows cast by the actors in the scene.

Sets for this scene were built on a large, rotating platform. The projection screen occupied an entire wall of the stage. The open nature of the set meant wider, steadier camera angles and little movement of the front projection rigging. Because of the set’s construction, the static shots used in the dawn of man sequence would have a realistic feel.

The dawn of man scene involved mimes, who played the apes. Dan Richter, who played Moonwatcher, said, “…the movement wasn’t the solution. The solution was to motivate the movement.” This meant Richter used the costumes and facial masks to motivate his movements. The masks were equipped with false lips, and teeth which could be moved by the actor’s tongue. The ape sounds were products of the actors, themselves.

This scene was shot after the rest of the production was finished.

Another of the film’s memorable effects was one in which a pen floats through space. This was achieved by gluing a pen to a sheet of glass, then rotating the glass.

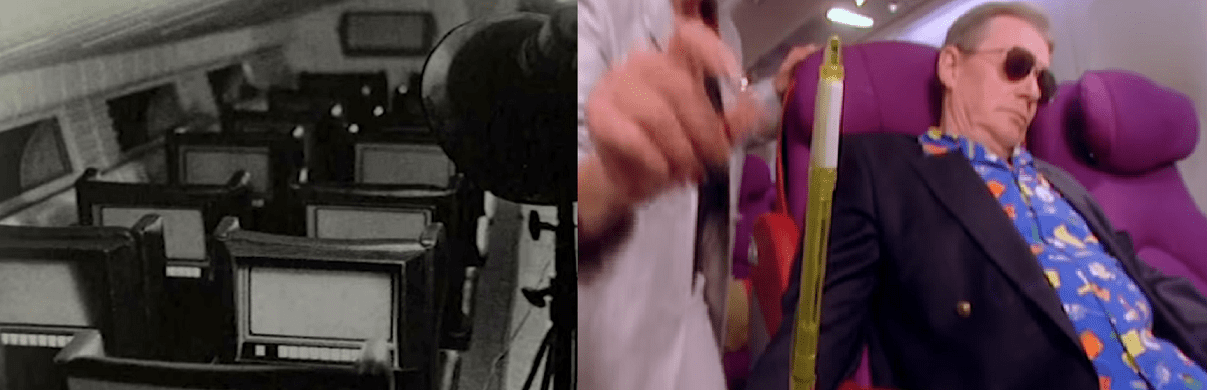

The interior screens showing different readouts were created in different ways. The main display showing a docking sequence was an actual film simulation including guidance corrections made by animation, not computer graphics. A thirty-five millimeter camera with a stop-motion motor was set up to record different artwork. This footage would then be animated for the different screens. Almost a thousand feet of animated work could be generated in a day. It took almost a full year to get the content for the displays, alone.

The Floyd sequence used a variety of stills and transparencies. Because an actual photo of the Earth would not be available until 1972, approximations of it would be used. The shot of the moving Ares is a still of a model two feet in diameter. The still was then manipulated in a way so it looked as though it were moving.

In many external and internal scenes, stars would be visible. Stars were made by drilling pinholes in very thin sheet metal, then mounted on tracks to produce simulated motion. Special cameras were then used to photograph the stars’ intensities. For scenes shot on an animation stand, stars were spatter-airbrushed onto glossy black paper and shot from six to twenty-four inches wide.

The moon surface for the practical scenes with the moon base was made from plaster. They then took a six inch brush and flicked the plaster with water as it set. All of the craters on the moon were made this way. The moon base, itself, was a four-feet by four-feet model. Landscapes were made by sculptures to get the finer details.

The IMDB page lists over twenty-five special effects technicians, including Brian Johnson, who worked on Empire Strikes Back, Aliens, and The Neverending Story.

For a more detailed, in-depth look at how Kubrick achieved many of 2001: A Space Odyssey‘s effects, YouTuber, CinemaTyler, offers some amazing insight.