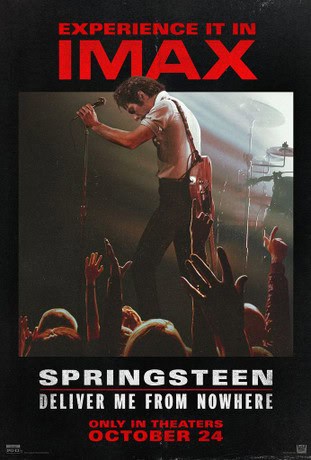

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere

Recap

Based on the book of the same name, Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere details the mental and emotional toll of legendary musician Bruce Springsteen's creative journey when writing the 1982 masterpiece, Nebraska.

Review

Biographical films within the vortex of mainstream Hollywood have become something of an intellectual laughingstock among the cinematically fluent and the pretentious alike. Dishonest crowd-pleasers at best, films like Bohemian Rhapsody have undermined the potential of exploring the journeys of living individuals who’ve had a massive impact on art and culture. However, in recent memory, the genre has been on a winning streak. Rocketman. A Better Man. A Complete Unknown. All massive blockbuster releases that have shattered creative ceilings and dug into the best and worst of the musicians they sought to immortalize on the silver screen.

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere joins them with a much quieter approach—focused almost entirely on a singular moment in the legendary musician’s history: the creation of his sixth album, Nebraska. A smoky and dark departure from what he’d come to be known for, it’s an odd place to start a biopic about a musician famous for his larger-than-life, communal persona. Yet in that sense, this juxtaposition between audience expectations—shaped by genre convention—and the depressive truth at the heart of Springsteen’s art is captured almost perfectly.

The chase for authenticity in every facet of this film is not just admirable, it’s the heart and soul of what Scott Cooper is striving for here. It’s a double-edged approach, though, as that authenticity seems to weigh a bit heavier in the film’s aesthetics than in its writing. Every frame feels like a memory ripped from the minds of Jersey kids like myself, who know that Asbury Park—and by proxy, the Stone Pony—are places of cultural melancholy, reflecting the escapism of a boardwalk town undercut by its own sense of fraudulence. It mirrors the journey Bruce himself is on, and that authentic marriage of environment, emotion, and character gives the film the juice it needs to keep audiences engaged with its singular exploration of silent trauma, generational depression, and isolative self-destruction.

However, the film leans so heavily on the brilliance of its cinematography to capture it all that it sometimes forgets to let the story sit with its characters as people. This is where genre pitfalls trip up an otherwise unique narrative—we spend more time watching Jeremy Allen White stare longingly at the horizon than we do digging into where those feelings come from as he slowly assembles Nebraska piece by piece. Exposition from those surrounding Bruce is often used to explain to the audience what he’s feeling and why, rather than letting those emotions surface naturally through our time with him. Emotional distance and melancholy are at the thematic core of Nebraska, so it makes sense that they’d inform how the film communicates its story—but here, that choice feels less purposeful and more like the product of voyeuristic scripting.

It’s fighting a battle between being a film about the creation of an album and one about a man’s battle with depression, and it never quite finds the depth needed to intertwine the two. Because of how strong the film making is, it doesn’t feel like there are two entirely different movies here—but rather two halves of a whole that are never given enough time to click. We speed through the recording of Nebraska due to the aforementioned lack of scene depth, and as a result, the time that could have been spent deepening our understanding of Bruce—time that would’ve lent his descent in the film’s later half more weight—is lost.

That undermines a film that is otherwise emotionally gripping from front to back. The performances are understated yet brilliant, with Jeremy Allen White proving himself a chameleon—able to express what the script often can’t when it comes to Bruce’s emotional strife. The supporting cast slips into their roles with little fanfare but enormous impact, especially Jeremy Strong and Stephen Graham, whose characters serve as a crucial dichotomy: the conflicting faces of masculinity that have seeded Bruce’s unspoken, quiet depression. Left in the wake of it all is Odessa Young’s Faye Romano, whose performance lies at the core of the film’s bittersweet theming—her independence as a woman never lost amid Bruce’s reclusive selfishness. The music, both original and from the Boss’s discography, is used so brilliantly and sparingly that the performance of it all takes the backseat necessary to make way for the human condition—and our relationship to it in solitude—that Cooper so desperately captures.

Final Thoughts

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere almost nails what could have been one of the best musician biopics in recent memory but stumbles in its scripting just enough to keep it from crossing that line between good and brilliant. It has so much to showcase and say, avoiding the shallow romanticization of depression as it explores the raw darkness within its subject, leaving most genre conventions by the wayside. It’s when those conventions needle their way back into the film that it starts to show some bruises.

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere – A Gilded Song

- Writing - 6/106/10

- Storyline - 7/107/10

- Acting - 9/109/10

- Music - 7/107/10

- Production - 8/108/10