We have an intimate relationship with our scars. Physical or emotional, we know the scars we bear better than anyone, and differently than anyone else ever can.

What intrigues me most about Fushigi Yugi, the Yu Watase comic that runs over a dozen volumes, is that it digs deep into scars and proposes a sociability that is performative; that social function via sociability outweighs individual trauma or damage.

He’s the sole support of his preteen siblings, pretending to be a greedy jerk to avoid intimacy. She’s a bag of exploding nerves and self-loathing who tries hard to be class clown. A romance!

Following Miaka, a teenaged daydreamer, between a not atypical home and school life that seems impossible to navigate, and her time in a magic universe kept within an old book, in which she is a messianic figure, Fushigi Yugi has the realness of irreality built into its every page. The art and writing range from the extremely cartooned to hyper-detailed romance to naturalist social scenes, sometimes within the same panel. The moment things become too real, or too threatening, the comic filters the reality out, the consequences, having become untenable to characters, are temporarily dissolved, unspokenly because they cannot handle them.

While the author has spoken, since its publication, of wishing she could go back and revise some of the handling of nonbinary characters or the treatment of potentially-transgender psychology, the unreliability of self-interpretation within the comic moves me more than a more researched or stable presentation might. In its way, it allows space, and shivers of uncertainty to examination of sexism and self-recrimination in queer, and as trans and non-binary people and as members of broader communities.

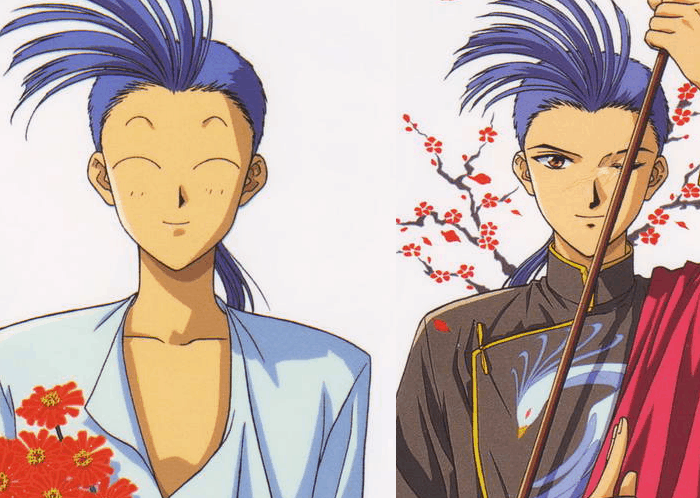

One of the most beloved supporting characters, Chichiri, presents as a constantly-smiling (he even has constantly smiling eyes), super cute – often so cute his body shrinks up into a superdeformed cutesy form – because he’s wearing a smiling mask that hides his scarred face and that everyone he ever loved is dead. His family are all dead. He was unable to save his best friend’s life. And, so he desperately tries to present a pleasing, comforting energy, and keep his scars and his fear inside.

Chichiri, with and without his smiling mask.

Even, our protagonist’s best friend, is in large, her best friend because it allows her to constantly belittle her, insult her, and watch her fail, which makes her feel better about herself.

Whether characters are trying to live out their dead sister’s life, keep their pain to themselves, hide compassion behind a facade of greed and efficacy, or having lunch with a classmate every day just to watch people laugh at her, they are all, in their way, wearing a mask, if not always as physical or literal of one as Chichiri. The comic will never take it too far, as it is disinterested in pretension and targeting a mature mid-teen readership, but the pain and masking channeled in Fushigi Yugi are genuine.

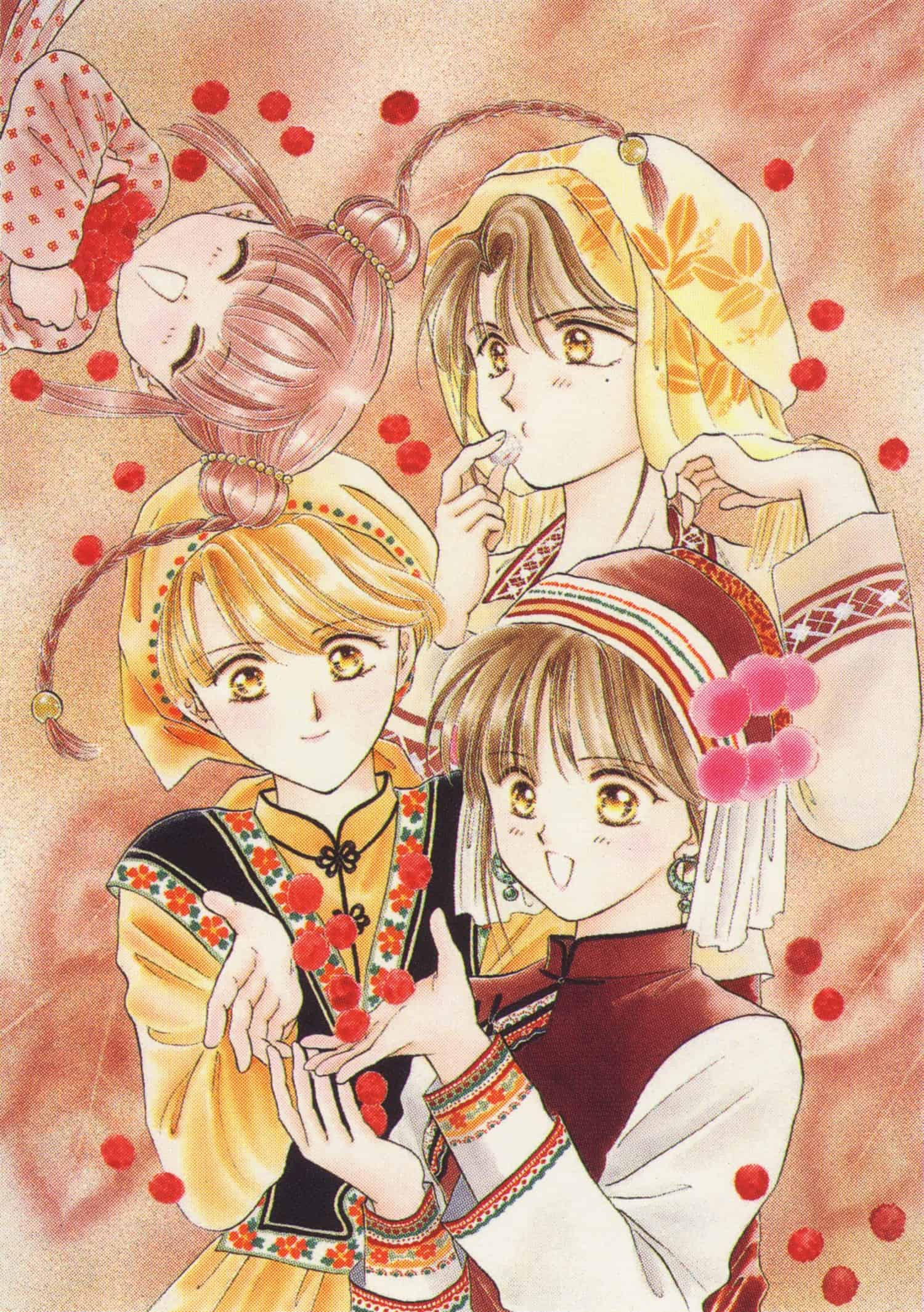

Three of these girls have been deeply hurt recently. The other is a goddess who lives a life of servitude.

And, too, they are comedy. Fushigi Yugi embraces farce. Miaka does pretty well in a fight by pretending she is a professional wrestler. She tries to hide from a wild animal by grabbing two branches off the ground and pretending to be a tree. When, friends or family reveal uncomfortable sides to her, Miaka’s strongest reactions are to pretend the unpleasantness away.

There is a lot of reality in farce. Each of us, as the characters in this comic, have done some ridiculous things. We have, at times, put our best foot forward, and with that foot, slipped on a banana peel.