Patricia Highsmash

Us Living in Fictional Cosmogonies

Epilogue: Beethoven’s Sonatas

by Travis Hedge Coke

Ludwig Van Beethoven, based on his death mask.

Ludwig van Beethoven composed thirty-two sonatas. Whether they comprise a cohesive evocation or an incomplete narrative is up to you.

At its most simple, a sonata is a piece of music played. Whether that is as opposed to being sung is a context for you to decide, as is, technically, the number of instruments. A sonata is an anticipation, not a technique.

A genre is anticipatory. A technique is a way of carrying out a procedure. A technique is precise. A genre is expectation.

As Beethoven said, “Music is the mediator between the spiritual and the sensual life.”

Beethoven was baptized on December 17, 1770 CE. He died on March 26, 1827. There is no record of his birth.

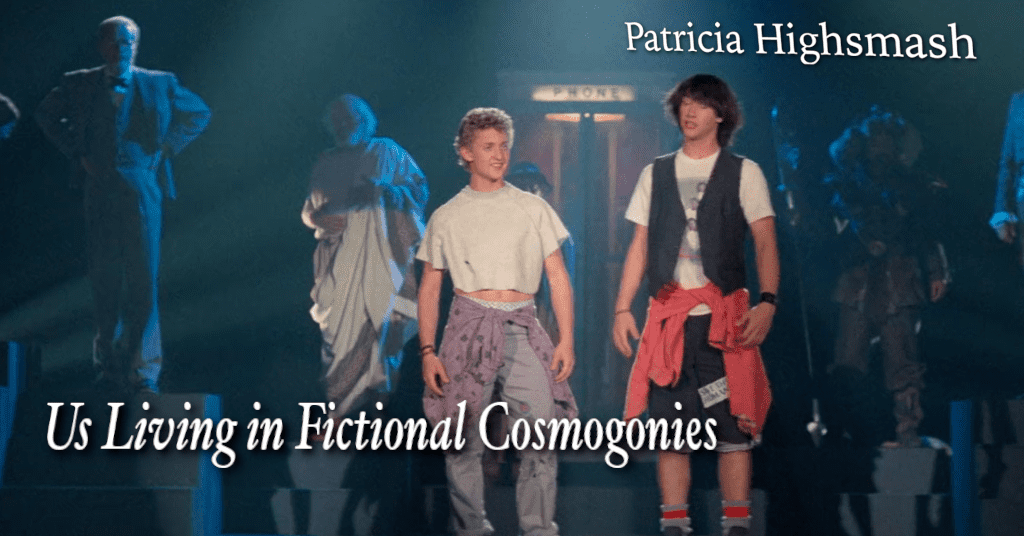

Bill S Preston, Esquire, and Ted “Theodore” Logan, based on Bill S Preston, Esquire, and Ted “Theodore” Logan.

Released in theaters on February 17, 1989, Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, directed by Stephen Herek from a script originally called Bill and Ted’s Time Van by Ed Solomon and Chris Matheson, taught us all to be excellent to each other, and to party on.

Alex Winter and Keanu Reeves would play Bill and Ted in another two films and for the first season of their 1990 animated television series. In the second season of that television series, and in its live action counterpart, they were played by Evan Richards and Christopher Kennedy, and in their original, pre-film form, Solomon and Matheson portrayed them in various improv sketches while in college in the late 1970s. Bill and Ted are as irrevocably linked to Winter and Reeves as they are mutable and universal enough to be played by anyone if the spirit is willing.

Throughout the theatrical movies, Bill and Ted are embodied and given voice by their mirroring daughters, by Hal Landon Jr, who plays Ted’s father but is for a time possessed by one of the duo, and by William Throne and Brendan Ryan, who portray them as regressed children.

That Bill + Ted energy.

Bill and Ted are played, as are sonatas. They are a genre, a subgenre even, more than anything so rigid as a technique. The Bill and Ted of the live action tv series possess many of the techniques that make a Bill and Ted, but most audiences, if they are made to remember that series, agree that it is not Bill and Ted. Even having all the earmarks, all the techniques that compiled should make up a Bill and Ted, may not make a Bill and Ted, just as evil or good robot Bill and Teds, in Bill and Ted’s Bogus Journey, are shown to be inaccurate Bill and Teds or, in Bill and Ted Face the Music, future progressions from our Bill and Ted are often disappointing and inaccurate, unacceptably not Bill and Ted enough.

“To play a wrong note is insignificant. To play without passion is inexcusable!” says Ludwig van Beethoven.

What Beethoven said – “What you are, you are by accident of birth; what I am, I am by myself. There are and will be a thousand princes; there is only one Beethoven” – is an uncivil fragment of what, “Be excellent to each other/party on, Dude,” can mean. There is one and there are many Bills and Teds. There will be a thousand princes, but each is an individual and a series of movements. There might be a thousand people with your name, or just one, but what is important is how you play and how you play with.

A large part of life is the feeling of being walked to the principal’s office.

Bill and Ted Face the Music is built to guide the title characters to a realization that a song has to be given.

Dave Wyndorf, of Monster Magnet and before that, Shrapnel, a great rock musician, a great performer, makes a distinction between going to be an event to be part of a performance and going to a performance to witness other people perform. That is a conscious choice we all make, and both have their value. For Wyndorf, he only wants to see or hear those he feels are truly talented, not necessarily people trying earnestly but falling short or just goofing off. Life, though, is too long and constant and brief and fluctuating, to be treated as a concert or by our concert preferences. Life has to be a performance for you by others and by you for yourself and others.

The unification of time and space and all people in time and space by Bill and Ted, in Face the Music, has to be distinct from them and embraceable by everyone. It needs a thousand princes as much as it needs one Beethoven. Life needs a thousand Beethovens and at least one person who works at Circle K and maybe does or does not know when a Mongolian Empire rule China.

Community examines itself, when it examines anything.

Ludwig van Beethoven himself, the famed, was the grandson of a famed Ludwig van Beethoven.

In the Bill and Ted world, Little Bill and Little Ted, their daughters, in many ways outpace their fathers, while it remains their father’s franchises and the lives of their fathers remain their own.

Weighing one life against another is the privilege of princes, generals, armchair gamblers and murderers, but it is always a privilege based on false premises.

That Bill and Ted traveled in time to the American Civil War to play a formative game of baseball with both Confederate and American soldiers, with Harriet Tubman and Dracula, is politically farcical and naive even by the good-humor standards of both Bill and Ted and the simplified version that is their cartoon universe, but in light of Face the Music, this is not moral relativism of the sort that asks teachers to pretend impartiality over Nazis and fascism or that refuses to address the horrific situation of Tubman in relation to the Confederacy. Bill and Ted are not refusing to make judgments or incapable of appraisals, but they are on a path to understanding the complex nature of history as both a vital and mutable thing.

What power Bill and Ted truly possess is perceptual as well as affecting. Like Neo, eventually, in The Matrix or the amnesiac victim in Dark City, Bill and Ted can and do alter reality. The past, as a recorded thing, and the future, as a mandated state, feel like a compilation of tandem techniques. This must be this way. This must be done like so. Which, is how we tell ourselves about our future, our past. We expect of ourselves. The past and future, like the present, is under no obligation to you, and your obligation would be weird if it was to dates or physical actions. The obligation is a social obligation, as is all history.

History has to look historical.

The figures who Bill and Ted interact with from history, famous, infamous, or relatively unknown, cannot be too historically accurate, historical scenarios must be cartoonish, because history, like the future, like the present, must be cartoonish enough to be plausibly malleable and to more significantly register with our emotions and our faith. An historically accurate Genghis Khan might be too complex, carry too much information and too many surprises, to be of educational use to Bill and Ted or narrative use to the plot of Excellent Adventure, but a cartoon Genghis Khan, as played by Al Leong, or Jane Wiedlin’s Joan of Arc, have an emotional existence, a purity of notion.

The location of the murder of Bill and Ted is the location on the last Star Trek episode we are shown in their universe, not the location in the episode’s story, but the location those scenes were shot in Bill and Ted’s (and in our own) reality. Reality and set, story and person, everything folds in.

Before they are to be executed in Medieval England, it is declared that they had “fire in their eyes, and they had horns,” which is untrue, but it makes a good story.

Bill and Ted history, present, and future are both era-as-narrative and being-in-narrative. The corrections of past and future are not deifying alterations of reality as much as emblematic of effortful living.

It is one thing if everyone or anyone is given the ability to alter history, or to shape the present, in as radical a fashion as what is allotted to Bill and Ted, but Bill and Ted are good guys. They are, in many ways, ahead of the social curve of their own time.

The future of Bill & Ted keeps changing, because the future is a long time.

And, in each of the three movies, Bill and Ted’s goodness is reaffirmed and it is, most importantly, corrected to reduce flaws in the signal. Casual – socially-accepted – sexism and homophobia give way in turns, because even as the characters were committed in those early portrayals, audiences refused to accept the appropriateness of those bigotries. In the first movie, Bill and Ted, themselves make a homophobic remark to distinguish their homosocial connection from something their specific culture and era was in opposition to, and this was met with distaste. In the next movie, their evil robot doubles utter homophobic remarks, because despite the general culture in which they exist still being homophobic, it cannot be Bill and Ted if they are. By the third movie, the homophobia has been excised from their and any doubles, duplicates, or echoes.

The offspring of Bill and Ted, ultimately who create the song which unites all space and time, can be presumed male at times, at other times, presumed female, can be considered non-binary, and exist undeniably queer to conventional heteronormative modern America. Little Bill and Little Ted, Billy and Thea, are transformative evocations of a Bill and Ted existing beyond them and beyond their fathers, beyond robot copies and temporal variants and possessing ghosts and bad sitcom adaptations. The actors portraying the adult Thea and Billy, Samara Weaving and Brigette Lundy-Paine respectively, made effort to costume their characters in homage to their fathers and to the presence of those fathers as not one’s dad and the other’s dad, but as “dads.” Bill and Ted are both parents to Thea and Billy, and their dynamic with their dads is not gender-entrenched.

Lundy-Paine acknowledged, of audiences who were upset over the inclusion of women and enbies in power positions in Bill and Ted Face the Music, that, “It’s scary to have your power taken away. But… this is how everyone else feels all the time.”

Death is a complicated guy.

The efforts of each Bill and Ted movie are not to get the duo or anyone else to functional mechanically in a rigid Rube Goldberg machine of time and plot, but to impart understanding of context and empathy, scale and connection. Like Sailor Moon’s Chibi Usa, or The Invisibles’ Lord Fanny, Bill and Ted make friends with Death. For Billy and Thea, Death is an uncle. Death is family. There is no hesitation in Ted or Bill to speak to Socrates, or even to philosophize along with him. They do not condemn Sigmund Freud or Napoleon Bonaparte, or attempt to redirect Joan of Arc or Satan. They have no classist disdain for workers, serfs, no apprehension about station or class. Their reference to their wives as “the princesses” is both an acknowledgment of their genuine political stature as princesses, but more than that, an evocation of their feeling about their wives.

Was Beethoven, Black? Was Beethoven of African descent and not the African descent that means thousands of years ago but in his immediate family? I am not going to ask, Does it matter? and if you are, please refer back to chapters One, Nine, Fourteen, and the Introduction to this book/series.

Played by white actor, Clifford David, in Excellent Adventure, the Bill and Ted Ludwig van Beethoven is portrayed as the average American high school textbook would have illustrated him, it is textbook accurate, as are the Abraham Lincoln, the Genghis Khan, and that kind of portrayal, that kind of in-world existence, is the sketch necessary for the sketched world of Bill and Ted.

History is pageantry.

The idea that Beethoven might be Black seems to first gain traction in 1907, long after his death, with the theory seeing resurgence in the 1940s, the 1960s, the 1990s, and the 2020. While some of the reasoning given has been exploited for racist purposes, there are also Black scholars and definably non-racist reasons for giving the theory credence or at least credence enough for consideration. Beethoven was broad-nosed, had a “blackish-brown complexion,” he was “stocky.” You make of these what you will.

For some people, the question of the veracity is less interesting, and less important, than how the idea came to be and how it has been used.

Representation happens.

What is the world of Bill and Ted if not the use of history, truth, the universe? Bill and Ted go to Hell when they die, for guilt over the silliest guilts, and when they break into Heaven, they immediately mug some people who deserve to be in Heaven. And, that is okeh. It is good. Hell and Heaven have no hold on Bill nor Ted, as they have no hold, in this world, on any of us. The government of the future lauds and condescends when it comes to Bill and Ted. They approve and disapprove and whatever to either.

When Bill S Preston, Esquire, was semi-seriously declared a trans icon by many fans, Bill’s actor, Winter, tweeted a trans flag. He tweeted the Black Trans Flag designed by Raquel Willis. Alex Winter and Bill S Preston are not Black, but to acknowledge the existence of Black people is a Bill S Preston move.

There has never been an apolitical Bill and Ted. There has never been an apolitical Beethoven sonata.