There Is Nothing Left to Say On The Invisibles

Boy Our Embarrassment

by Travis Hedge Coke

In the end, Boy understands the secret purposes of life and the universe afore Jack Frost or King Mob.

What is a 1988 Black policewoman in America?

Like how Sam Wilson is a better person than Steve Rogers from his moment of introduction in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, how Malcolm X is an infinitely superior person in all ways to Marvel Comics’ Magneto, and how we are willing to go along with – or at least grumblingly tolerate – the “Magneto is based on Malcolm X” lie – Boy rarely gets her due in lieu of declaring Jack Frost “the one who gets it”, the “little buddha”, the wise child who sayeth, “Fuck.”

The boy in The Invisibles is not, Boy, which is yet a disparaging term used by racists to refer to nonwhite adult men. Boy reflects, in that people read her as masc, a tendency of some white storytellers to portray a masc-read to Black women, or a recurring trope of short-haired Black girls disguised as boys.

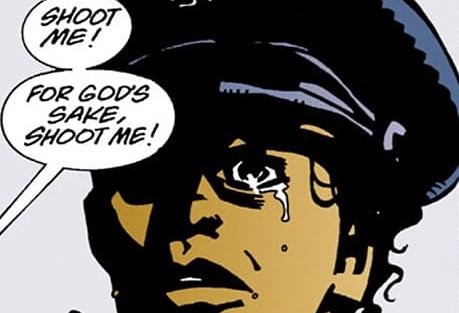

Imagine being Boy. You have been a police. You have been a secret counteragent. A family member. A dutiful daughter. Careful sister. You are an excellent hand to hand fighter, you know guns and takedowns, you know tactics. You have firsthand experience with the evils people do, the colonizing corruption machine, the cosmic whatness. And, you shut up about all of it. You big up your white colleagues, because being a fighter, a shooter, a leader, a lawgiver, a mystically awakened or socially aware person is part of their shaping mystiques. You flinch if someone gives you grief for reading Maya Angelou. You worry you come off like a sitcom caricature. The manicured Cosby Show Black woman. Or, a girl. Or, a tagalong.

For most readers of The Invisibles, Boy is a source of embarrassment. We are embarrassed for her, we are embarrassed of her, we are embarrassed for not knowing how to think of her or what to do with what we know of her. Much in the same manner her family are embarrassed by, for, and about her, but rarely do we reflect on that.

Boy demonstrates more shame and humility, more constant awareness that she was a willing and eager police in a corrupt policing machine, than Mason Lang or King Mob or Lady Edith Manning ever show of their monied white tourism days. Does not make them bad people, but it is something Boy cannot even talk to them about. When other (white) Invisibles call Boy “self-contained”, or distant, it begs a question of who she was supposed to talk with.

I am calling us all racist and sexist and regionalist and problematic. We have bad cues and bad gauges planted in our heads for us and it behooves us to keep watch on them, to make our own corrections, which we do not always do. Past critique of Boy, of how Boy is as a person and character, how she is handled by contributors to the comics, by critics and fans and audiences extant the comic, come together to strongly indicate we do not adjust the gauges enough.

Boy, despite her name, is not young when we encounter her in The Invisibles. Even in her flashbacks to ye days of yore, like, How I Became Invisible, she is not young. She is ostensibly less magical or spiritual than Lord Fanny or King Mob. Less science adept than Satoh Takashi or Ragged Robin. Less of a great fighter than Jolly Roger. And, she is often framed – particularly by other characters – as less knowledgable, less worldly, than many of the characters, particularly white anglos with more money than she will ever see.

A specter of Boy’s similarity to Monkey in Quadrophenia, a musical invoked by the chant of the gang of pre-Jack Dane, the actual boy boy of The Invisibles, hangs an ugly shroud of pervasive racism across the world, and not only Boy’s existence. Her existence will always be marred by a racism we bring in, a sexism we bring in, both of which she has internalized.

We know from what we know of her life that Boy has had a full adult life before she even became indoctrinated into the Invisible order, and what we can sort as plausible from fictionalized, as Boy has several lives, or memories, at points, which are not reflective of reality, but refractive; the glosses of mind-control, hypnosis, ritual and role-play. Boy has known death and struggle and politics and confusion as well as anyone else in her cell, our primary cast, but is framed as the steady one, or the normal one, the basic one.

Boy is, in many ways, representative of air as a mystic element, a social element. And, we forget air is there. “Fish don’t know they’re wet.” Well, neither do we on the deep dive.

Unlike many we are intimate with, during The Invisibles, Boy knows she is an Invisible, she is indoctrinated and affirmed, long before her personal encounter with Barbelith, the placental organ of existence. And, unlike those we know encountered Barbelith before or early in their Invisibleness, she does not, afterwards, continue the fight, the fake war which enmeshes King Mob, Jack Frost, et al.

Boy wears many names and identities across her life and the spectra of our experiences with her stories in The Invisibles and they are all in ways false or adopted and in similar (sometimes the precisely same) ways, they are all true, real being. An alias is an identity. A nickname can be an intimate portrait or a casual sketch of a person.

In There is Nothing Left to Say (On The Invisibles), I will have to keep referring to Lucille Butler, Little Sister, Officer Butler, Maya, Michelle Brady, Lucille, Mistress, Sister, Mom as separate individuals, separate characters, along with other names and identities, but they occupy one contiguous and continuous bodily form, except when they do not. She is a revolutionary, a relative, a police, a nun, a soldier, a spy, a lover, a parent, a retiree, a teacher, a kid. Her compatriots, like King Mob, can be Mob and a novelist, Kirk Morrison, and a kid, Gideon Starorzewski; a retiree, Gideon Starorzewski; a performance, Stargrave. And, in the end, Boy is Gideon and Gideon is Boy. We are all ourselves and each other. Lucille Butler and Octavia Butler. Maya and Maya and Maya and Maya and Maya.

We praise Jack for understanding something of community and identity and togetherness and love and empathy when he has his Barbelith encounters or he does something kind or forgiving.

In the issue titled, How I Became Invisible, Boy writes a confessional letter to herself, in which she details her “apocalypse,” her personal awakening, which is illustrated for us by a scene of late-1980s December in which white spots are spattered across the panels like snowfall and like the white of the blank badge eating away at the complexity and colorization of our faux reality, as seen when Jack experiences his apocalypse, the 2012 “end of the world,” in the final issue of The Invisibles.

Boy dedicates her life to being good to the community, the world, the Earth, people, herself, and life after she is met by Barbelith. She saw the white snow fall in the air above the occupied streets more than twenty years before Jack Frost will.

Boy does not, as Jack does, partially get it. She gets it.

Boy is on the money.

And, we fail to give her credit for this because we are too caught up in the fake fight, the spectacle, and white people with guns. While we internalize white significance, and arrested adolescence, Boy gets wise and lives a good life.

Boy is the axle of the wheel of her cell. The Hecate, the Hadit, the cloak and dagger. The layered identicals, the laddered identities. Boy drops her adopted identities faster and easier than some we see, but she is judged harsher for her struggle in doing so. Existing as a Black woman leaves Boy subject to assumptions and frustrations by non-Black and Black characters alike.

Unlike white King Mob’s white ex, Jacqui, Boy opts out of the play-acting-with-real-murder without letting fly any misogyny or deflection of men’s responsibility for themselves. Unlike Jack, she gets it immediately and takes direct action. Boy does not let Barbelith and a shaved head turn her into a murderer. She does not let past actions as a police, a terrorist, or a teacher overwhelm her contemporary life and what she can accomplish.

Money and credit. Police and uniforms. Memories and morality plays.

Even Boy believes, at least for awhile, that she cannot fathom the high science or high magic that Mob or Fanny do. That she might be less spiritual than the others. Her choice of reading material and her adoption of Maya as a name are mocked by other Invisibles as trite. Her choice to have a child is often derided by readers and critics of the comic.

King Mob’s heaven, his final experience where he gets all he wants is paparazzi, fanfare, continuous lights and camera paffs. He is a celebrity in a celebrity seat. Incest, pride, applause, riding high on the crest of inquiring minds who want to know.

Jack’s is either him holding his childhood friend he left behind, sharing his life with him, or talking to us while everything goes white.

Boy misses out on seeing Jack before everyone gets their heaven. Mob goes to see her and she has her applause, her fanfare. She has a kid with her, she looks good. She keeps in shape to keep in shape, not to murder people.

“I stopped needing to save the world”, she said to Jack once. “Saving is what misers do.”

He leaves this world trying to figure that out. So, why is our faith on him, why is our bet on him and not Boy?

Boy slips in and out of history and the game like Billy “Brilliant” Chang, a real life, true crime celebrity of the time figure who is given, in real life, and in The Invisibles, great significance, but little praise or attention. His accomplishments are extraordinary, but must be downplayed to emphasize the drama of less enlightened white people.

Sassy gay friend. Wise ethnic visitor. The perceived incivility of discussing how much minorities and oppressed peoples are good allies to those who, by the service to their demographics, are empowered, gives us The Help or The Legend of Bagger Vance and the here and the now. Anthony Bouviers are always on trial. An oppressed person is expected to go extra miles carrying or returning to check on the dominating class and its individual members.

We must take care and make effort to not say “nonwhite” or “ethnic minorities”, when we mean, specifically, Black.

It is unfortunate that even among leftist, liberal, or informed white-dominated groups, that ethnic minorities, once they have their one, are so often pushed out or reduced, but it becomes difficult to tell when someone leaves for their freedom or when a group is closing ranks.

NEXT: Once I Was a Little Light

And previously:

- Prologue/Series Bible

- Chapter One: I Was a Librarian’s Assistant (Pt. 1)

- Chapter Two: I Was a Librarian’s Assistant (Pt. 2)

- Chapter Three: Robin Roundabout

- Chapter Four: How Did Helga Get in Here?

*******

Nothing in There is Nothing Left to Say (On The Invisibles) is guaranteed factually correct, in part or in toto, nor aroused or recommended as ethically or metaphysically sound, and the same is true of the following recommendations we hope will nonetheless be illuminating to you, our most discriminating audience.

Morrison, Grant. The Invisibles. Jill Thompson, Chris Weston, et al. DC Comics. 1994-2000.

Quadrophenia. 1979. Directed by Franc Roddam. Based on the rock opera by The Who.

Ellison, Ralph. Invisible Man. 1952. Random House.

Cultural Criticism and Transformation. 1997. Directed by Sut Jhally. Presented by bell hooks.