What does police fiction look like in 2022?

The genre is well-worn, dating back to the pulps of the 1920s and ’30s and even before, in a broader sense if we consider variations on a theme within their respective historical contexts. And for much of its history, it has tended to present police in a pretty black and white framework: cops (usually white) good, criminals (usually minorities) bad. That’s part of a wider narrative that has tended to place the police on pedestals, presenting them as above reproach. There are countless examples to the contrary, of course, but the power of a good lie is that when it’s repeated often enough, it becomes a kind of truth.

Nevertheless, police fiction has persisted across the decades: the jaded Popeye O’Doyles and Dirty Harries of the 1970s gave way to the cop on the edge of the ’80s, who in turn gave way to the charming rogue of the ’90s. These archetypes all had one thing in common: they were the law, but they were also above the law as they deemed fit, so long the ends justified the means in their (and their superiors’) minds. That alternate reality in fiction helped feed the real-world fiction that cops actually should be allowed to operate with impunity, to which of course fueled decade upon decade of system abuse toward minorities that went utterly unchecked. Periodic reckonings such as the L.A. riots would flare up and bring national attention to the issue, and talking heads would take to cable to discuss the need for systemic change and accountability, but by and large, “the blue wall of silence” was too high to be overcome. Police, protected by one of (if not the) most powerful unions in the country, were in most instances legally untouchable, a class separate from those they were supposed to be protecting.

Interestingly, though, where novels and movies failed to keep up with the times, TV took two branching paths. One, enshrined by Dick Wolf’s never-ending Law & Order universe, sticks to the script of the black and white, cops-good-criminals-bad narrative with a high degree of success for over thirty years. And, look – from a purely escapist perspective, the various Law & Order shows work. They present neat, tidy, easily-digestible morality plays where good typically triumphs over evil on a weekly basis with little deviation, and although the shows occasionally pay lip service to “the need for change” or focus on a stereotypical “bad apple cop,” at the end of the day (and in Wolf’s own paraphrased words), the shows are “the greatest recruitment tool for police ever made.” Their procedural format has proven so effective at consistently reeling in viewers, that it spawned a cottage industry of like-minded pro-law enforcement propaganda such as NCIS, Criminal Minds, the Hawaii Five-Oh reboot, and countless more. A good chunk of people, it seems, prefer the unnuanced fiction to the uncomfortable reality.

The other path, though, trailblazed by In the Heat of the Night and Hill Street Blues, took a more human approach to the act of being law enforcement. Endings rarely if ever came neatly and tidily, racism existed, inequality existed, and the police themselves were seldom paragons of virtue. More often than not, these shows treated their police protagonists for what they truly are: flawed people being asked to make decisions and choices most of us would find impossible on a daily basis, and while some of them were the better for it, none of them were saints. Officers got burnt out, drank too much (in a non-romanticized kind of way), made poor decisions, and, effectively had to deal with the consequences of their actions. Shows like Homicide: Life on the Street and NYPD Blue elevated this approach to something akin to an art form, and by the 2000s, The Wire perfected it by focusing on the larger tapestry of how law enforcement was entangled in communities and then The Shield went the opposite direction by starring an unabashedly corrupt cop, the immortal bastard Vic Mackey.

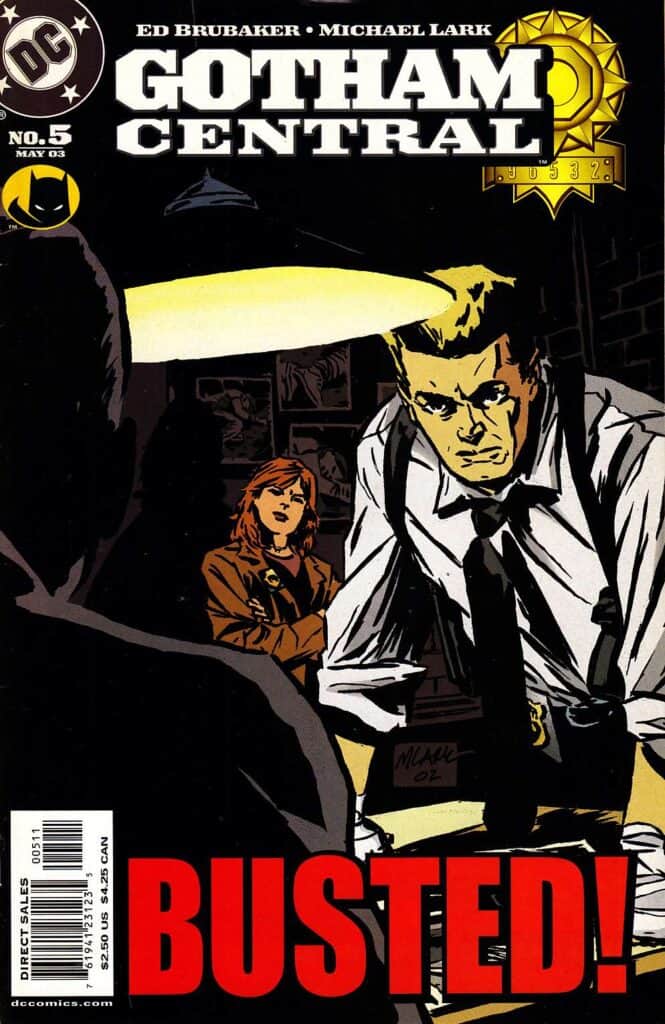

It’s the latter path that informed DC’s brilliant Gotham Central, written by Ed Brubaker and Greg Rucka and illustrated by a then-new Michael Lark. Running from 2003 to 2006, Gotham Central took the “flawed cop in a flawed system” approach of Homicide and threw it into the world of Batman, the Joker, Mr. Freeze, et al. How would an officer function in a world like that? What does it mean to uphold the law when there’s a man in a bat costume leaving made-up henchmen tied to light posts? What does that say about the efficacy of the law, when Gotham wants to have it both ways: a competent, accountable police force somehow living harmoniously with an extralegal vigilante? In the final assessment, it meant exactly what you’d expect: that nothing is easy, nothing is black and white, and the idea that there’s a straightforward fix for the inequities that plague the American criminal justice system is laughable. Gotham Central was a triumph in storytelling when it came out, and it still holds up today. No copaganda here. The police fiction genre could thrive in the 21st Century, it seemed, provided a responsible approach was taken to the subject matter.

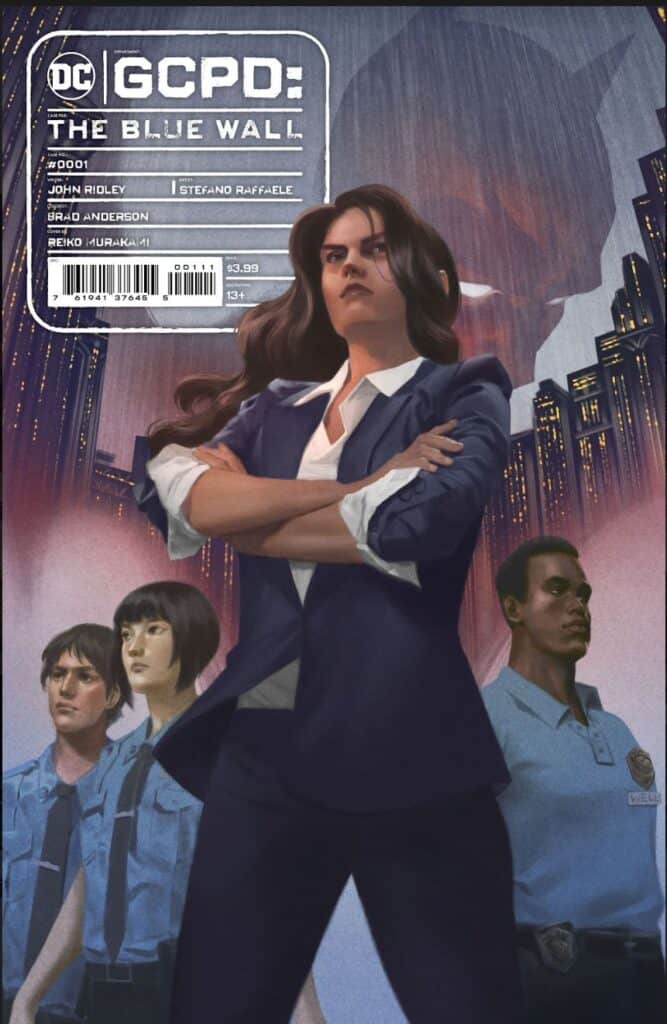

It’s been awhile since DC wholeheartedly gave the Gotham Central approach to one of their comics, but this week, they’re giving it the old college try again with GCPD: The Blue Wall by Oscar-winning screenwriter John Ridley and artist Stefano Raffaele. Ridley, no stranger to sensitive subject matter (on top of winning that Oscar for 12 Years a Slave, he had the raw nerve to introduce the world to a Black Batman and absolutely run wild with it), is up against a nearly-impossible task, though:

He’s trying to write this story in the shadow of George Floyd, Black Lives Matter, Say Her Name, Defund the Police, and a thousand other cultural flashpoints that have radically divided our national perception of law enforcement in a radically short amount of time. Or, rather, sharpened both sides’ perceptions: on the Right, the enshrinement of police as untouchable and unaccountable is more entrenched than ever; on the Left, the police are every bit as much a threat as criminals, perhaps more so as they have a blue wall to hide behind that will forever protect them from accountability. Left out of the conversation is any hint or suggestion of nuance.

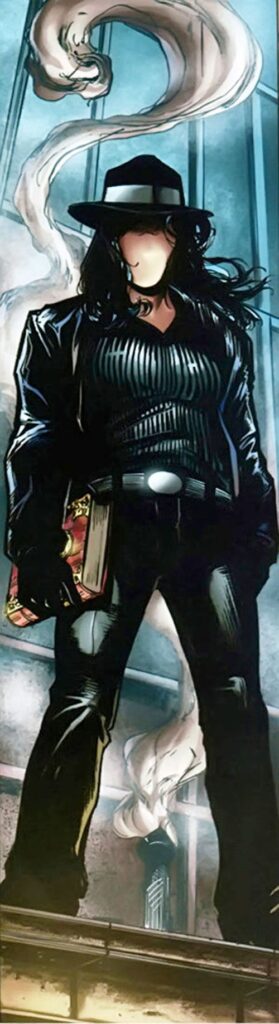

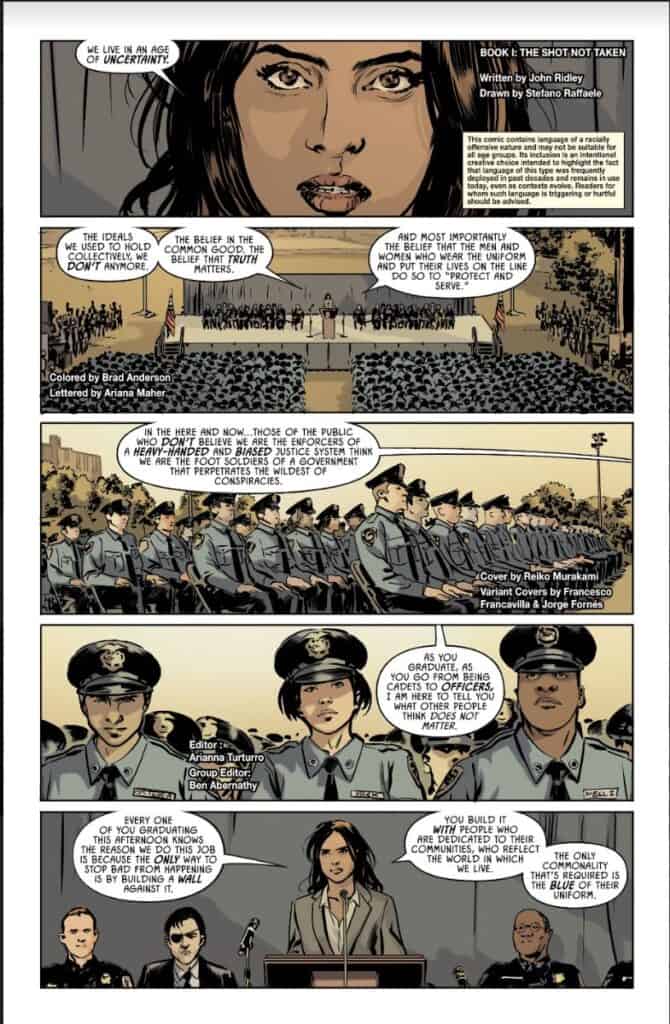

And so, into that yawning chasm steps Ridley’s GCPD: The Blue Wall, a comic that definitely wants to play middleman between the two sides, and address that lack of nuance and perspective riven in our society. It’s a difficult challenge, and I have to tip my hat to Ridley for even attempting it – let alone DC for playing along. Renee Montoya, now elevated to the status of Police Commissioner (Jim Gordon is retired, at least for the time being until some future writer decides to restore the status quo). Her own uneasy history as a police is one that included being publicly outed as gay by Two-Face and eventually quitting, disillusioned after her partner was murdered by a corrupt cop (who got away with it) and left a barely-functional alcoholic. She gradually found a new path and became the new Question, taking the mantle from Vic Sage and becoming a more socially responsible, openly gay hero. Of course, that was a long while ago, and comics have a routine habit of always returning to the factory setting, so now Montoya is a cop again and grumpy old fans like me are just going to have to deal with how regressive that is.

Montoya’s regression isn’t the point, though. In her new capacity as commissioner, she can’t just wave a wand and fix the GCPD’s ills. They’re called systemic problems for a reason – they’re baked into the very DNA of the police and the scaffolding that supports it, which is vast, multilayered, and densely convoluted. Just like in real life. That’s a tough pill to swallow, but in her heart, Montoya still believes that the idea of what the police can be is worth fighting for. Change may be glacial, but with the right people in place, it can happen. That’s the kernel of faith that keeps Montoya going, even as she has to effectively pimp a rookie officer out as a public relations coup for not firing her weapon at an unarmed Black teenager.

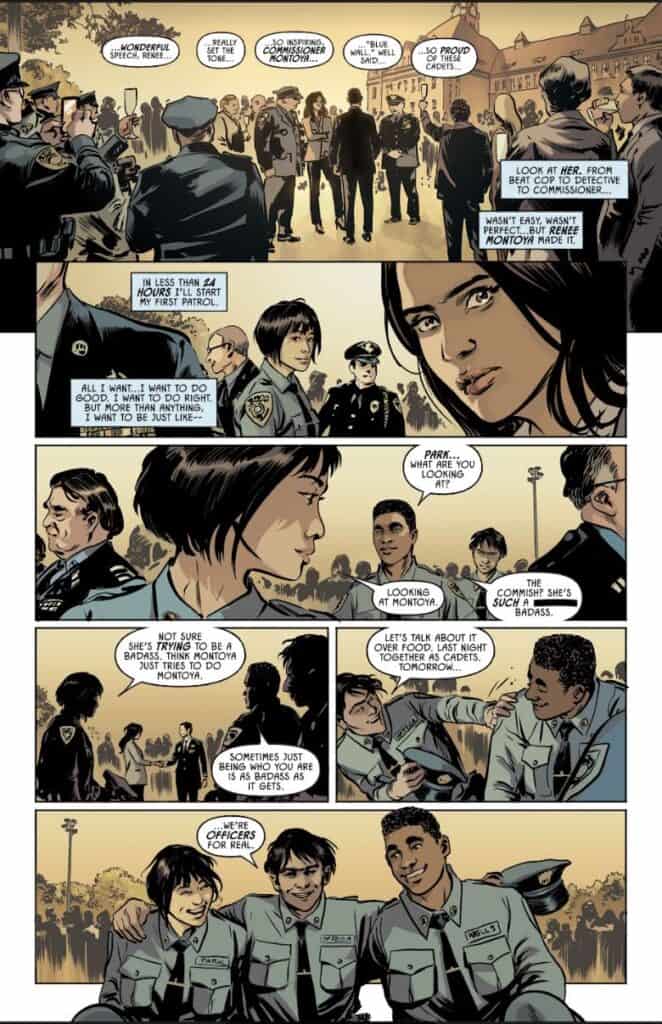

The police officers in GCPD: The Blue Wall are of many various stripes and walks of life. The counterpoint to Montoya’s weary resignation are three rookies, fresh out of the academy and full of excitement at the possibilities before them. Of the characters presented in the narrative, they’re probably the three who hew closest to the idea of copaganda, or at least, its tendency to portray officers as though they’re always inherently Good Guys. That warm and fuzzy feeling doesn’t last, though, as the realities of the job begin to almost immediately weigh on them.

One is called an ethnic slur by the desk sergeant at his new assignment; another, a parole officer, is psychologically beat down by his superior on day one because he wants to impart hope on a justice-involved young man; the third as described above nearly murdered someone right out of the gate. Almost right away, the realities of being in law enforcement begin to chip away at their youthful idealism.

However, this is also where Ridley’s narrative stumbles a bit by trying to have it both ways. In attempting to present the rookies as all optimistic, inherently good people, he inadvertently paints a picture that all who join the ranks of law enforcement have good intentions, which simply isn’t true. In fairness, it also isn’t true that all cops are jackbooted, racist thugs beyond accountability, but because of where Ridley’s narrative begins, it can’t help but portray that optimistic viewpoint as the reality.

But what the narrative does adequately convey is that the system of American law enforcement can inevitably beat down even the most ardent, well-intended cadet. Maybe they’ll quit, or maybe they’ll eventually succumb to the mechanisms that prevent meaningful change. But the bottom line, Ridley tells us, is that the system isn’t incapable of change – it’s that it doesn’t want to change at all. And that’s the problem with not only the system of law enforcement, but the healthcare system, the political system, the housing system, the employment system – they exist to support a status quo, not to grow, change, and evolve to meet the needs of the now. They’re dependent on people who depend on that stability, and thus have little to no incentive to try to incite change. GCPD: The Blue Wall hints at that monolithic, inescapable stagnation, but at least in its initial issue, doesn’t quite nail its own thesis – the perils of trying to bridge the gap between two inherently conflicting perspectives, of Right versus Left, conservative versus progressive, MAGA versus Hope and Change.

That isn’t to say this is a bad comic. Far from it. It’s engaging, and sets up a multitude of potential subplots to take it in as many different directions as it wants. In fact, based on its subtitle, I was plainly afraid that “The Blue Wall” was actually a play on the whole “thin blue line between order and chaos” schtick currently playing out on a thousand thousand jacked-up pickup truck bumper stickers – which is unequivocally propaganda if ever there was any. But nor is it a “Defund the Police” manifesto. The blue wall in question is the system itself that allows the corruption, pessimism, and unvarying rigidity to flourish unchecked, resulting in a bloated police force that is content to leave things as they are rather than rise to the challenge of positive change to meet the times we live in. It’s raison d’etre lies somewhere between the two, which is an intriguing prospect: it’s asking readers as much as the police system to look inwardly and think outside the box for change, without sacrificing safety and security. It’s possibly a fool’s gambit, but is it one worth trying anyway? GCPD: The Blue Wall may not ultimately have the answers, but thus far, it’s unafraid to ask the right questions.