Patricia Highsmash

Examining New X-Men Pt 5

by Travis Hedge Coke

From 2001 to 2004 Grant Morrison (The Invisibles, Batman and Robin) and team of pencilers, inkers, letterers, editors and colorists, including Phil Jimenez, Mike Marts, and Frank Quitely made a comic called New X-Men.

Revitalizing the X-Men as a politically savvy, fashion forward superhero soap opera, New X-Men was published by Marvel Comics as the flagship of a line wide revival.

“Cassandra has no concept of cooperation, Hank. That’s how will beat her.”

– from Grant Morrison’s New X-Men

“Individuality leads to nothing but trouble in X-Men.”

– Grant Morrison on New X-Men

Grant Morrison, Igor Kordey, Hi Fi, Saida T!

Pt 5

Working Alongside

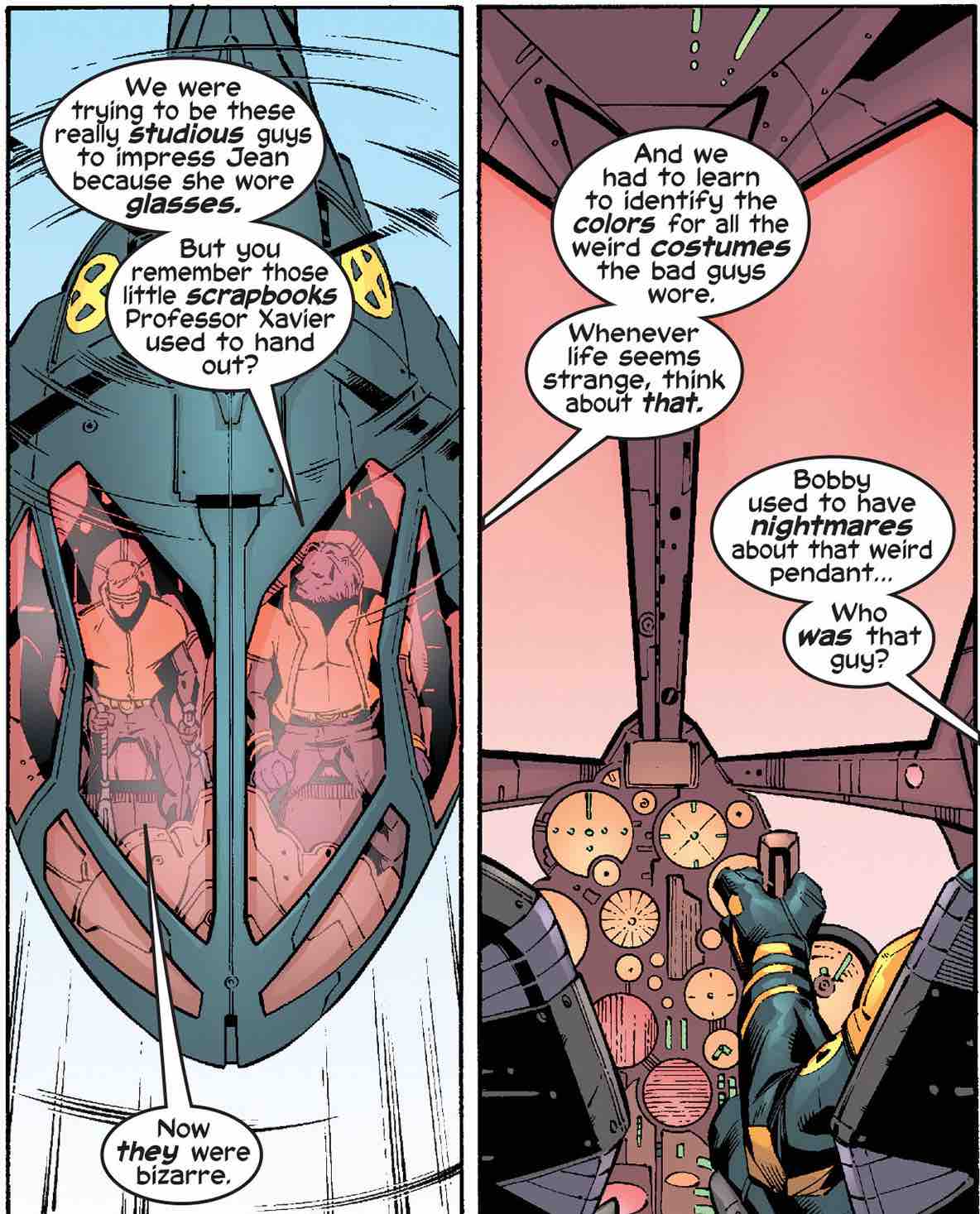

For more than forty issues, New X-Men stressed cooperation and collaboration, integration and solidarity. And over the course of the production of those issues, the people who made New X-Men benefitted from those features and sometimes experienced their lack.

Editorial miscommunication became infamous in professional and fan circles. Artists sometimes felt bullied or lied to. Ultimately, Grant Morrison would, somewhat publicly, quit the title and publisher due to anger and frustration with upper management.

The period during which New X-Men was serialized would be the first time that Chris Claremont was writing an X-Men title, but was not the driving force of the comics line. Claremont had to do significant rewrites to his first year on X-Treme X-Men, including removing a major character he had plotted for a year of stories, in part due to Grant Morrison’s contract allowing them priority.

Chris Claremont, Salvador Larroca, Tom Orzechowski, Liquid!

In Tom DeFalco’s Comics Creators on X-Men, Claremont, the writer more associated with X-Men than any other, had this to say about when he wrote X-Teme X-Men and Morrison was writing New X-Men:

“Guys come in with agendas. Grant Morrison came in with a Manifesto that outlined thirty-odd issues of New X-Men. This is what he’s going to do and basically what he did with a couple of tweaks along the way. The problem is that at the end of the thirty-odd issues, the canon was left in ruins. Grant doesn’t care. He’s off writing Superman.”

Claremont was the regular writer on the comic that became New X-Men and returned as regular writer on Uncanny X-Men shortly after Morrison’s New X-Men finished.

Morrison was on the comic, New X-Men, for just over forty comics, from 2001 the 2004. Neither Claremont nor Morrison own any of the comics, character, or concepts developed or created for their X-Men comics.

In that same collection of interviews with Tom DeFalco, Grant Morrison says of Claremont that, “Chris was very gracious. He always checked what everyone was doing and tried to incorporate it into what he was doing on X-Treme X-Men.

“He kept his eye on what everyone was doing and filled in the gaps.”

Some of the lack of cooperation perceived by talent became fodder and fuel for the comics and characterizations. The worlds of New X-Men become an experiment and how we can come together, in accepting, assisting and understanding.

“The idea behind a lot of what I was doing in X-Men,” Grant Morrison told Jay Babcock for Arthur, “is to give these future supermen a template, to say ‘Okay you’re a superhuman, and maybe it feels a little like this. I’ve tried really hard as one of the last of the human beings to think what it might be like in your world.’ Rather than bring them to us, which is what a lot of superhero fiction in the past has tried to do, I’ve tried to go into their world and to understand.”

X-Men comics have long been infamous for characters and narrative being readily forgiving. The X-Men will put put a serial killer on a team, letting them live in their house, if it seems the understanding thing to do or simply pragmatic.

An undercurrent to New X-Men, is that Emma Frost used to be a supervillain.

Not originally part of Morrison’s plans for New X-Men, Frost’s involvement was generated spontaneously during a public online conversation, when a prospective reader enquired as to her use.

Characters in New X-Men cast doubt on Emma with consistency, from Beast (mirroring a moment from an early 60s X-Men comic, in which his fellow X-Men cast doubt on him) to Sage (who, as a spy, saw him up close and personal daily during her worst years). Within issues of Beast casting doubt, he is her most determined defendant, but others will never forgive her, except to tolerate and work alongside her.

Frost was a member of a worldwide criminal cabal/sex club during the comics published as happening in the present day, from 1980 to 1991. Through her electronics empire, she participated in the creation and refinement of machines for oppressing, and for the murder of mutants. She participated in kidnappings, body swaps, animal abuse and violent assaults.

Amongst those who would become her fellow X-Men, alone, Frost is complicit in the sexual assault of both Storm and Jean Grey. When Dr Grey saves Frost’s life, and disinfects all of her possession by the ancient entitty, Sublime, Grey is fully aware she is helping someone who was directly involved in a sick manipulation of her life, and someone who right at that moment is engaged in an affair with her husband.

At the end of New X-Men, Jean Grey, having died, blesses the union of her widower and Emma Frost.

Without that suggestion from a fan, we would not have Frost’s presence or impact, which entirely altered the run of New X-Men.

The X-Men will be forgiving, and embracing, and helpful, until somebody dies.

But, they will also constantly remind you of your failings, if you are not fully in the club.

Collaboration is hard.

Quentin Quire forms of fascist gang, assaults people in the street, stages of a school-wide riot that results in multiple deaths, and the X-Men tell him that he could have, instead, submitted his criticisms in the form of a written essay.

Fantomex and EVA lie to the X-Men, cheat them, manipulate them, and are each time welcomed with open arms and understanding.

Igor Kordey, Dave McCaig, Grant Morrison, Saida T!

The great tragedy of Magneto’s long slow con, disguising himself to the point of using an artificial, magnetically generated voice, trolling the X-Men, teaching classes, fighting battles he has no interest in, revenge and an attempt to conquer the world, is that if he had simply showed up on their doorstep and asked to get along with them, they would have agreed.

If Magneto would stop kidnapping, assaulting, impressing children into his armies, trying to conquer the world, the X-Men would be completely chill with him. They want to be completely chill with him, something the last fifteen or so years of X-Men comics have borne out.

Instead of just being a good person, Magneto pretends be a good person because it’s a way of being a jerk.

When he conquers New York City, Magneto gives grand speeches that virtually no one can hear because he is too far away from them, bringing one moment to a crescendo with, “We will have no need for bridges,” which sounds inspiring. He talks of a “we” who can fly, leap, swim. And, he talks of them right and destroys the Brooklyn Bridge right next to people, largely children, who cannot fly, easily swim, or remotely leap the length of that bridge.

That is what Magneto’s speech truly communicates. Eugenic supremacy. Be great for him.

Phil Jimenez, Andy Lanning, Chris Chuckry, Grant Morrison

Magneto – and Morrison has admitted in large part him channeling frustrations with miscommunication and the lack of cooperation in real life – becomes an emblem for all failed communication, all failed cooperation.

When Joe Casey’s Nazi-themed X-Corps (a half-satirical mutant “superhero” team based in brutal police tactics, and appearing in Uncanny X-Men) bombed hard with readers and critics, Morrison repurposed the positive aspects, as X-Corp, a specifically rehabilitative effort rooted in correcting the wrong-headedness of X-Corps, dialing back the militarism and hard edges, for counseling offices, first responder teams, and press releases.

X-Corp is a localized branch of X-Men in every community, in spirit, but in reality, they are sometimes overtasked in locations and overly concentrated in others. The Beijing offices know they are deprioritized despite a huge, heavily populated territory.

In New X-Men, even concurrent storylines from other titles could become efforts at correction, restitution, and contrite outreach. And, they can be ways to explore the limitations or failings of goodwill when faced with time, finance, and power concerns.

It is apropos that the issue most sympathetic to the good of Magneto, Ambient Magnetic Fields, steps away from most of the New X-Men regulars to focus on characters Chris Claremont’s X-Treme X-Men – Thunderbird (the one from India, not any of the Native American Thunderbirds) and Storm (characters closely associated with Claremont), Sabra (the Israeli state superhero), as well as family and longtime associates of Magneto (Polaris, Toad, Paralyzer).

Claremont’s stylistic influence is on every page of New X-Men, but with Ambient Magnetic Fields it takes over, allowing for political relativism and grandiloquent speeches in the classic Claremont vein.

As the X-Statix comic soared in critical acclaim, characters appeared in New X-Men as keychains. When an investigation into a murder required someone outside their immediate cast, Morrison borrowed from Claremont’s X-Treme X-Men characters, Claremont having repositioned his X-Men team into police, for an investigatory team who could play to the procedural maneuvers while enhancing both the distance between the casts and the understood bonds.

Famous for introducing many new characters, most created by Grant Morrison, others, like Glob Herman, created by artists and developed by Morrison and other artists, New X-Men continually reintroduced characters from previous and concurrent X-runs.

Keron Grant, Grant Morrison, Norm Rapmund

In its way, borrowing characters from X-Treme X-Men, world-building from X-Statix, revisiting El Tigre, a character created in 1966, who had not even been mentioned for over twenty years, by smoothly integrating plot lines from The Twelve and The Search for Cyclops, adapting techniques and expectations brought in from the movies, New X-Men was, itself, an attempt at a bridge for those who could not leap, fly, will teleport story to story, title to title.

Werner Roth, Roy Thomas, Sam Rosen, Dick Ayers

Throughout New X-Men, attempts are made welcome, to inform and educate and care for people of all demographics, all walks and types. In Planet X and Here Comes Tomorrow, we see humans and self-aware machines as X-Men. We see the Xavier Institute permit protests right outside their gates, as well as the school open those gates for outreach to non-mutant humans, including press conferences and an open house.

The Xavier Institute has former supervillains, former criminals on staff and as students, from Emma Frost to Ernst, a violent rage monster who destroyed an intergalactic empire and committed every crime from mass murder to rape.

Charles Xavier makes many mistakes and assumes too much, but the narrative of New X-Men rewards the enthusiasm of his ethos even when it fails in particular incidents or to correct the direction of the boat of life over the course of generations.

Everything can go wrong in the world, people can be hurt, the trails can occur, good intentions and cause damage, without making the acting on good intentions or the having of good intentions a flawed or bad thing.

In the words of EVA, one hundred and fifty years from present day, “We figured an inter species group of X-Men might be the only way forward in a conflict like this one.”

In the words of Tom Skylark, who may be the last surviving non-mutant human on Earth, “Never mind integration… I want payback.”

EVA and Tom are two modes in the same scenario, two forms of partnership.

EVA, even when she is the brains and nervous system, is a support network astronaut. She steps back and lets others have the spotlight. She’s a chair for Charles Xavier. She’s a friend. A cover.

Tom Skylark is as friendly as EVA, and very tight with his partners, empathetic to communities, but he and his partner operate as Rover and I, not Tom and I. Skylark and Them. That I. The last human standing and holding to that I. “I.” “I.”

Outreach, no matter how many times there is a risk of injury what difficulty, remains a noble, necessary, integral effort. Outreach, collaboration, integration is hard. We cannot expect everyone to approach it with the same energy or motives.

The first humans we see in New X-Men are a video of ancient people supposedly murdering another kind of people.

Andy Lanning, Grant Morrison, Phil Jimenez, Rus Wooton

The first human we see on an X-Men team in New X-Men, a New York police officer only standing alongside the team for one scene, is the butt of some casual anti-human jokes from Beast, the venting a frustration here we go systemically abusive human world. He rolls with them, but they are there.

The solemn, humanizing funeral some U-Men attend is a sniping, selfish arbitration over divvying up the riches of the deceased, this case not external, but actual parts of the corpse. Cooperation is not the absence a self-interest, of selfishness. Much cooperation comes directly from self-interest.

In the world of New X-Men, that self-interest may not be our own. Sublime, an ancient multi-body intelligence, predating mutants, humans, even dinosaurs, lives within every person, and is able to exert control over every non-mutant human is so subtle of fashion that people are unaware how they’re being controlled.

Through the addictive aerosol, kick, Sublime is it able to exert the same subtle control over mutants.

It is impossible to determine what difficulties in human experience, what selfishness, what complications with collaboration are the fault of Sublime inside and affecting everyone. Nagging doubts, sudden inspiration, rising fears might all be Sublime, or they could be us.

Sublime has difficulty affecting mutants the way they can all other earthly lifeforms, and yet, mutants also experience problems with cooperating, with collective interest. Is the issue cultural? Biological? Psychological?

“The menace of the Beast unites us all.” The thousand dollar biblical summation of New X-Men and all X-Men. We are fighting together against old crimes and baser instincts.

In New X-Men, psychology and biology, the physical and the spiritual, are inseparable. As mutants develop more common and frequent psychic traits, there is also a rise in people and other lifeforms that seemed designed to predate on, or to work around those psychic traits.

The feeders, seen in Here Comes Tomorrow as a new terrestrial life, like Cassandra Nova, are predators who hunger for telepaths. Minds such as the “see-thru” Quentin Quire, the viral and sporing consciousness of the Huntsman, the shared hive mind of the Stepford Cuckoos, the tandem minds of EVA and Fantomex, EVA’s ability to bond with organic life, even the psychic bonds that Jean Grey seems so inclined to establishing are as much social growths as physiological or psychic.

Fantomex and EVA are a danger because of their ability and willingness to lie, but in EVA is evidence of a capacity for an individual to act as a support for another individual, to open oneself.

Quentin Quire, with his imperceptible thoughts and his power to be convincing, ruins the lives of several of his fellow students. Quire is at the same time a mutation fostering an individuality that, without those traits, could be at risk.

Magneto’s capacity for sounding like the voice of experience and reason is able to horribly twist others to his will, particularly the uncertain, the vulnerable. Magneto’s conviction and eloquence are not a mutation, but given by his experiences, by his life.

And, that is not true. Magneto, canonically, has a “magnetic personality.” One of his mutant abilities is how convincing he can be.

As readers we can decide if Magneto, in a moment, is making a good point, but in their world, if you are hearing him in person, how do you know?

The two pillars of mutant politics are a man who is superhumanly convincing and a man who is the most powerful telepath on Earth.

We can grope, we can experiment, we can trust. These are the limitations of humans and mutants in New X-Men, and they are our limitations. The Phoenix, as an entity, as an empowerment, as a perspective, can be outside of those limits, but to be outside the limits, requires being outside.

Jean Grey is able to take Sublime in hand and remove them from their place in what we would consider us and our world, when she is Phoenix, and even in that state, she is one of a corps of Phoenix, a collective distanced from and intimately invested in every page, panel, color and line of New X-Men.

The reason Cassandra Nova turns to speak to us, in Here Comes Tomorrow, is that for the betterment of New X-Men, for our own compassion and development, there is a collaboration between us and the comic, between us and the authors, between us and other audience. And, whether it makes us nervous, feel stupid, embarrassed, there is a collaboration between us and the characters.

Grant Morrison, Marc Silvestri, Joe Weems, Billy Tan