The western comic world was built in pairs. Stan and Jack, Bob and Bill, Joe and Jerry. These famed creative duos have created more American legends than anyone else, but unless you’re a true blue comics fan, the names Gardener and Carmine often fly under the radar for no good reason. Gardener Fox and Carmine Infantino are the sleekest creative duo of their time, their silver age tales often ahead of their time and fantastic to revisit even to this day. The magic of silver age comics, and what the modern age has lost throughout time in comparison, can be found in every comic book that these two of touched, together or otherwise.

In the face of mass exposure and the insistence on cameos over complexity, superhero media on a large scale has faced creative sterilization. The multiverse was once a whimsical frontier for engaging and exciting superhero stories, but people now fear the concept will only be used to show off other versions of things you love in hopes you buy more toys instead of more comics. There’s a significant lack of creative risk associated with the multiverse now thanks to Hollywood’s use of it for nostalgia dominated purposes. However, the roots of its whimsy, which began with The Flash #123 by Gardener and Fox, are growing blurry in the modern day.

So let’s race back to the core thematic purpose of the alternate universe story alongside Barry Allen and the Flash of Earth-Two, Jay Garrick.

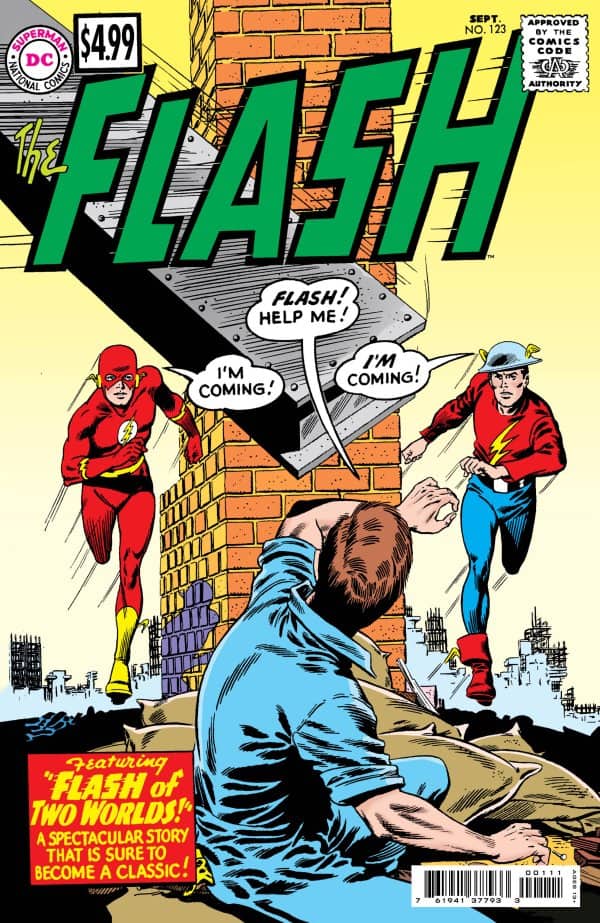

Facsimile Edition Cover (2023)

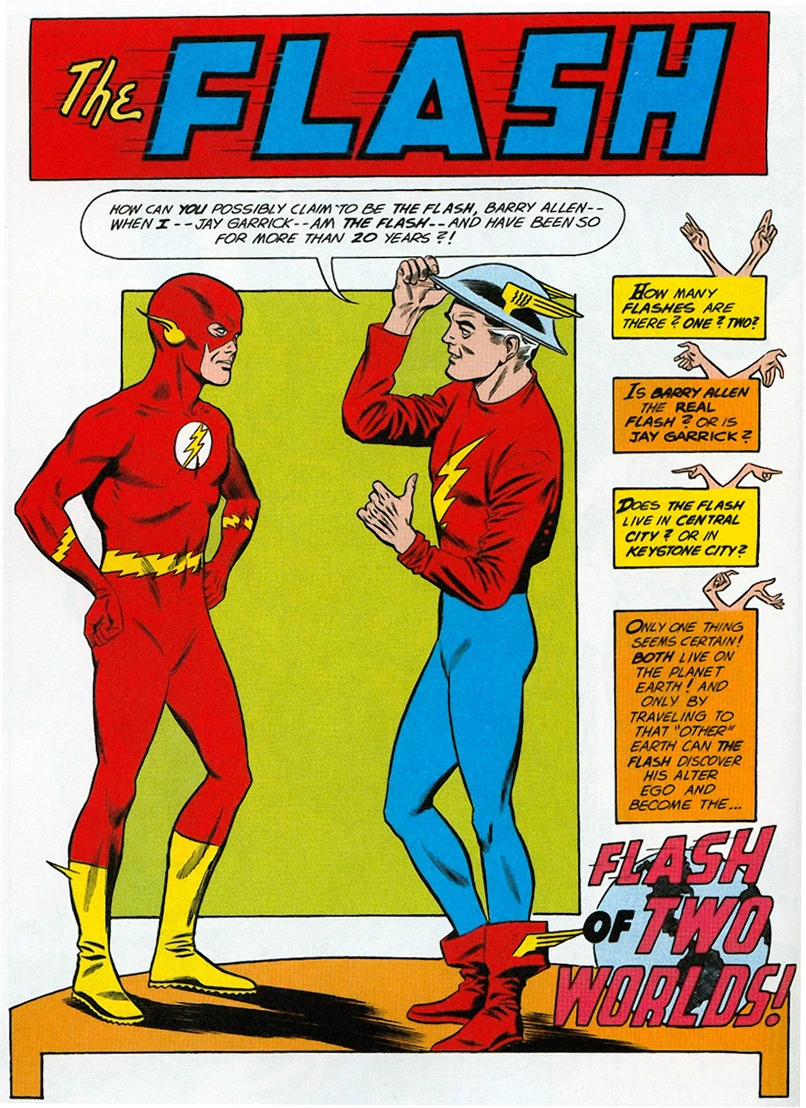

“Barry Allen travels to Earth-Two and encounters Jay Garrick, The Flash of Earth-Two. Who is the real Flash, Barry Allen or Jay Garrick? This classic Silver Age story resurrected the Golden Age Flash and provided a foundation for the Multiverse homes from which he and the Silver Age Flash would hail. It was fitting that the historic meeting between the two Flashes should be written by Gardner Fox and drawn by Carmine Infantino, who had both chronicled the adventures of the Golden Age Flash in the 1940s. The creative duo sent the Silver Age Flash, Barry Allen, through an interdimensional rift to a parallel Earth where he would meet the childhood idol he had read about in “Flash Comics.” Allen’s timing couldn’t have been better: Jay Garrick, now 20 years older, had just decided to come out of retirement in the midst of a mysterious crime wave in Keystone City – a string of thefts by his old arch nemesis the Thinker, the Shade and the Fiddler.The Flashes became fast friends, and tracked down the dastardly trio to the Keystone City Museum, where they thwarted the villains’ plan to steal rare gems. The experience motivated Jay Garrick to remain out of retirement, while Barry Allen returned home to track down Flash Comic’s writer Gardner Fox and tell him of the fantastic adventure he had just shared with his ‘creation.’ (League of Geeks Official Summary).”

Before we dive directly into the story, I have to make some mention of Carmine Infantino’s art. It stands tall as dynamic, expressive, and bright in such a way that I could see his influence on the modern day directly in his own pencils. Both Flashes are distinct, and his panel to panel storytelling concise and drawn without waste. This issue is paced with a near perfect three act structure in small thanks to Infantino’s visual storytelling. He’s a legend for a reason, and pairing his sleek artistic style with Fox’s dialogue writing that was leagues beyond the competition at the time allowed this decades old box to flow and read just as well as the day’s old The Flash #800.

The use of the multiverse in this plot serves to revitalize and re-contextualize the character of Jay Garrick within the wider continuity of the DC Universe through an emotionally suggestive story rich with fun and creativity. The concept of an alternate universe here is used to serve the story that Fox & Infantio are trying to tell, instead of the story serving this mythological concept. Because of this, ‘The Flash of Two Worlds’ is allowed to have its cake and eat it too. Yes, it slides Jay Garrick back into continuity in a way that makes sense, the use of multiversal dream theory and imaginative decisions in terms of story justification. Yet, even in the face of that, the issue is allowed to have a true blue superhero tale at its core.

The Flashes have to work with one another to take down the string of strange crimes popping up all over Keystone city, the antagonists of this tale being something both Flashes have to take down. However, the reason why this story has to exist, is that Barry’s love and admiration of Jay is what beats his self-doubt and pulls him back out of retirement for the greater good. There’s a small kernel of thematic storytelling here that’s just potent enough to raise this book above the realm of pulp, which isn’t out of the norm for silver age comics.

That small conceptual kernel is the heart of this concept. The multiverse marries new and old together in order to tell stories and bolster characters up in a way that can’t be done within a rigid continuity. Sometimes that marriage comes in the form of radical re-imagining. Superman: Red Son and The Dark Knight Returns are great examples of this in comics. For this story in particular, the multiverse is used to crossover the characters of new and old in order to revitalize the characters in fun and exciting ways. See the recent Batman #135 as an example of this story trope.

There isn’t a referential obsession on display with this story. Instead, there’s an earnest attempt at elevating our heroes by having them work and learn from one another. When it lacks depth, the multiverse concept can become bait for the nostalgic, which of course leads people to assume that any instance of cameo/crossover writing in a multiverse story is cheap. When done right however, you get a classic tale in the same vein as The Flash #123.