For this last day of Pride Month 2022, we thought we’d re-present Lillian Hochwender’s beautiful, thought-provoking three-part analysis on Loki’s genderfluidity. Enjoy!

Content Warning: transphobia, homophobia

This is Part 2 of a short series exploring Loki’s genderfluidity in Marvel. Part 1 contains definitions of genderfluidity and background on Loki. It also analyzes the transphobia surrounding J. Michael Straczynski’s and Olivier Coipel’s “Lady Loki” and the affirming story of Loki: Agent of Asgard.

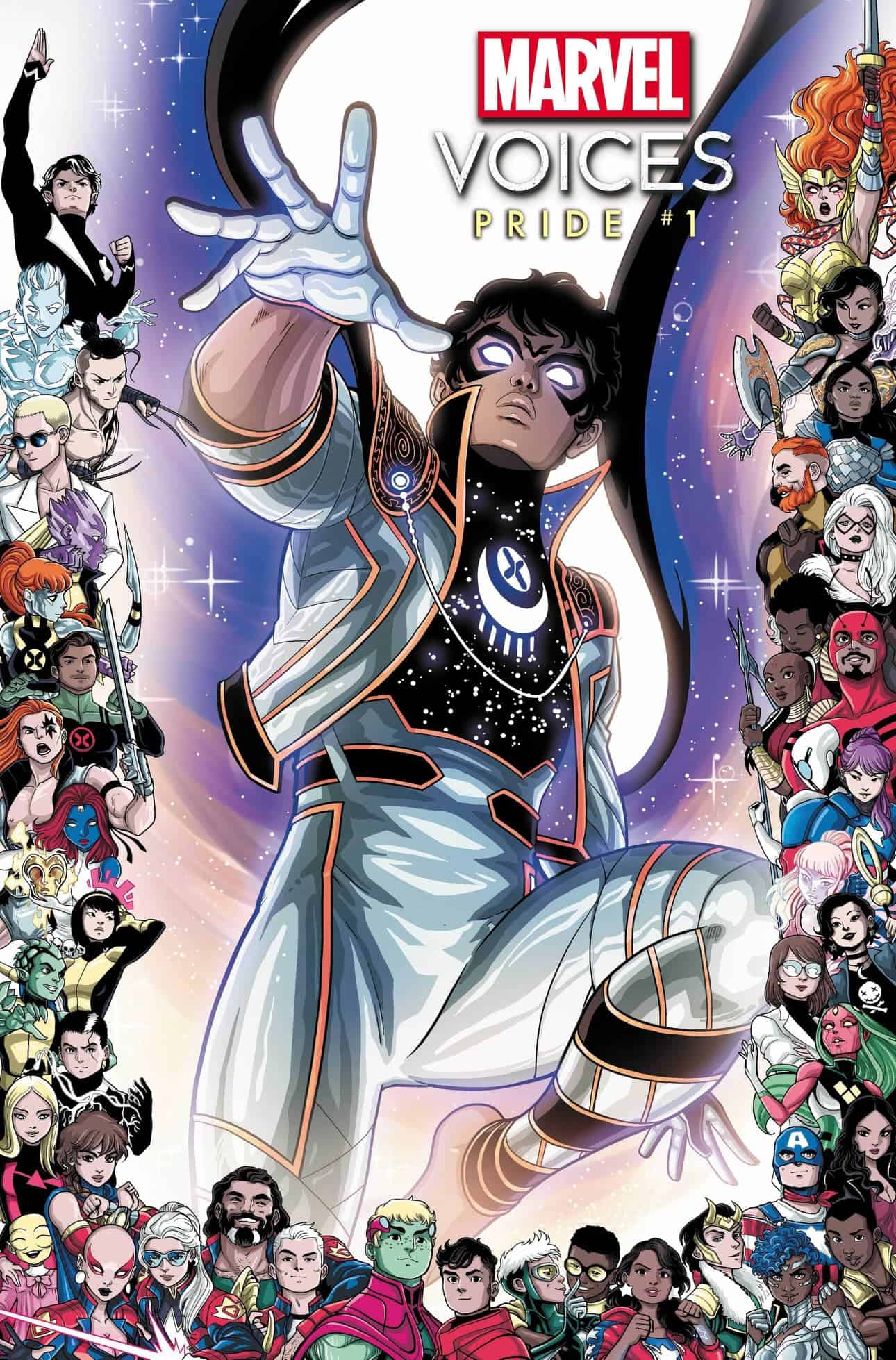

This month, Marvel Comics published Marvel’s Voices: Pride: an anthology highlighting not just Marvel’s LGBT+ characters but LGBT+ artists and writers. However, readers familiar with Loki may be surprised to find Marvel’s iteration of the Norse god strangely absent. For a while, he wasn’t even on its cover. His absence grew even more glaring in the light of Disney+’s Loki show confirming that the God of Mischief would be genderfluid in the MCU. He was also confirmed as bisexual in episode 3, making him the MCU’s first non-straight protagonist. (“Bisexual” is often defined as attraction to two or more genders, or attraction to different and similar genders.) Truthfully, beyond Loki: Agent of Asgard, representations of Loki in the comics — specifically in regards to Loki’s genderfluidity — have been mixed. There have been some good or decent depictions, but Loki’s genderfluidity more often than not gets erased or burdened by old character design. I can’t answer why Marvel didn’t give more attention to a character who is now unquestionably its most famous trans character. However, via this case study of Loki, I hope to offer a constructive look at how far Marvel has come in its depictions of trans people and how much still needs to change.

The final cover of Marvel’s Voices: Pride (2021)

“We’re Turning Into Nothings!”: Loki, Queer Erasure, and the Comics Code Authority

As even Loki seems aware, stories are at the mercy of their tellers; and writers — artists — people in general — often default to something old rather than embracing change. Loki’s genderfluidity dates back to Norse myth, and nonbinary conceptions of gender are far older than the United States. Nonetheless, Loki’s genderfluidity is a recent addition for Marvel.

At Marvel, trans characters are relatively rare and mostly minor. At this point, Loki is the only trans Marvel character to have had a solo title. Yet, Thor comics — the place readers are still most likely to encounter Loki in comics — have never (to my knowledge) addressed Loki’s genderfluidity. It’s not essential that Loki’s genderfluidity be an element of conversation in every Thor issue, but to ignore it contributes to the continued erasure of trans people.

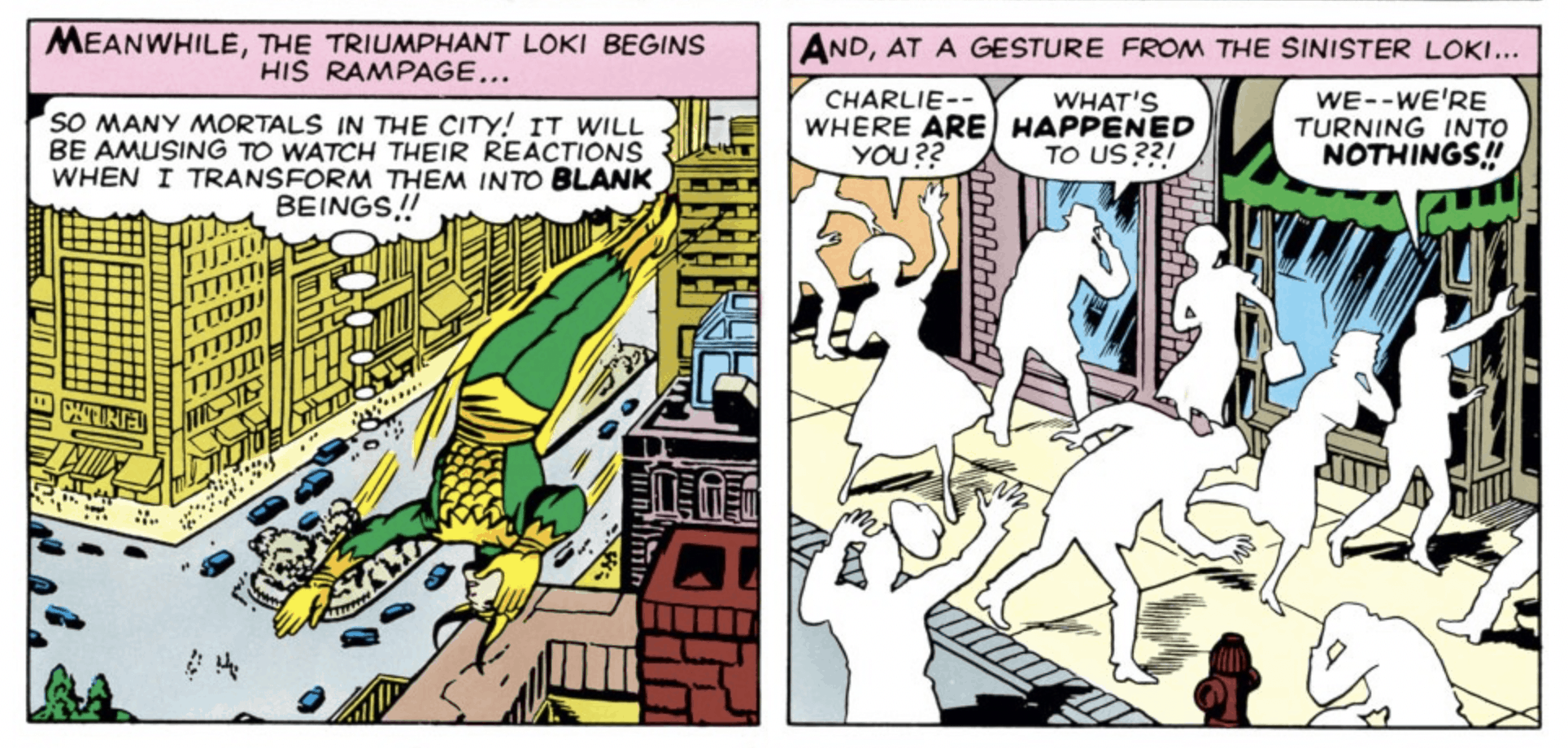

In Journey Into Mystery #88 (his second comic book appearance), Loki indulges in a number of high jinks, making guns grow wings and turning a street to ice-cream. He also turns a bunch of people into “nothings”: blank spaces shown by a dotted black line. These antics are common fare in early Marvel, but this moment of turning people into “nothings” becomes a poignant image of how Marvel has treated its queer characters. The phenomenon is called “queer erasure.” Wikipedia (which actually has the best definition) defines “queer erasure” as “a heteronormative cultural tendency to remove queer groups intentionally or unintentionally from record, or to dismiss or downplay their significance.” Historically, Marvel has done both. A related term — “straightwashing” — also applies to fiction: a version of queer erasure when a fictional character previously established as queer is treated as straight or cisgender.

To fully understand the harm of queer erasure and straightwashing, and why modern trans representation remains scarce, it’s important to understand the historical context of comic book censorship. Many comics fans are undoubtedly aware of the Comics Code Authority — even if it’s via seeing the CCA’s approval stamp on older books. Ostensibly created to combat juvenile delinquency, the CCA was a self-regulatory agency that often used its power of censorship to enforce bigoted conservative ideology.

The burning of 2000 comic books in Binghamton NY, 20 December 1948 (Time Magazine)

In 1954, psychiatrist Fredric Wertham published Seduction of the Innocent, a book in which he claimed that comics — then dominated by the horror and crime genres — were a harmful medium causing juvenile delinquency. In decades since, other researchers have pointed out the numerous ways Wertham falsified evidence to support his thesis. While Wertham’s book spends lengthy sections addressing things like werewolves and vampires, he also set his sights on another supposed monster: queer people. One chapter of Wertham’s book (titled “I Want to be a Sex Maniac!”) claims to find homosexual undertones in Batman and Wonder Woman and argues that these undertones ultimately corrupt children. Filled with stories of trauma and physical abuse, Seduction of the Innocent horrified its adult audience and added to an already mounting nationwide moral panic against comics. After Wertham appeared at a Senate hearing on juvenile delinquency, comics publishers decided to come together and form the CCA, which would require every comic to adhere to a strict set of rules before it was given a CCA approval stamp. Without the stamp, distributors were likely to deny a comic distribution, meaning the book wouldn’t sell — thus encouraging publishers to stick firmly to the CCA’s rules.

The Comics Code didn’t exist in a vacuum, but was in fact inspired by the Motion Picture Association of America, which continues to determine film ratings, though its original code (“the Hays Code”) was retired in 1968. (Part 3 will discuss the Hays Code more in depth, along with its relationship with modern film and the MCU’s generally conservative approach to queerness.)

In October of 1954, the first version of the Comics Code went into effect. Some of the code’s rules specifically targeted the horror genre. Comics were no longer allowed to contain the words “horror” or “terror” in their titles; they couldn’t feature vampires, zombies, or werewolves; and they couldn’t depict excessive gore or bloodshed. Other rules were more banal: for example, “good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds.” However, some CCA rules were more directly inspired by the MPAA’s Hays Code, in particular the bans on “sexual abnormalities” and “sex perversion.” The Hays Code stated “SEX PERVERSION or any inference to it is forbidden,” which the CCA adopted almost word for word. “Sex perversion”/“sexual abnormalities” included depictions of transgender people and of homosexuality (both of which were still defined as mental illnesses by the American Psychiatric Association at the time). Publishers — and thus artists and writers — did their best to stay on the “safe” side of the CCA’s vague wording; it could be difficult to tell where the CCA would draw its line, and to be on the wrong side of that line meant no stamp; no stamp meant no money. When the Comics Code was revised in 1971, it became more lenient about horror depictions, for example; but “sexual abnormalities” and “sex perversion” both stayed as they were. It wasn’t until the Code’s final revision in 1989 when the rules were rewritten to state “Character portrayals will be carefully crafted and show sensitivity to national, ethnic, religious, sexual, political and socioeconomic orientations.”

In 2001, Marvel Comics abandoned the Code in favor of its own in-house ratings system. DC Comics eventually gave up the Code in 2011. However, the Comics Code still left its mark on how books were censored and rated. At Marvel, Editor-in-Chief Jim Shooter has been described as having “no gays in the Marvel universe” rule through the 1980s, while under Joe Quesada queer characters were often relegated to adult/mature-rated books.

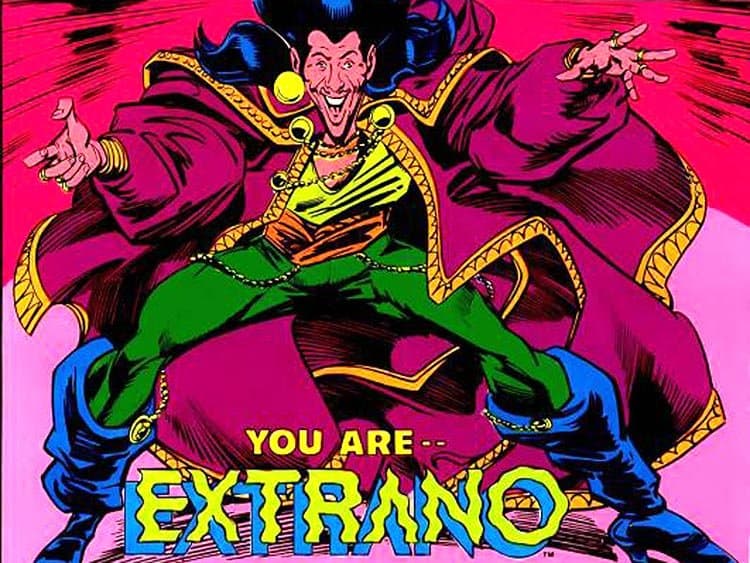

Because Code-era comics couldn’t depict actual queer characters, creators often turned to something called “queer-coding,” which had also become a dominant method of depicting queerness in Hays Code-era Hollywood, and even in novels in centuries previous. Queer-coding relies on degrading stereotypes of queer people in lieu of real representation. For example, DC Comics had a minor hero in the 80s called Extraño (Spanish for “Strange”) who was flamboyant, called himself “Auntie,” and died of AIDS. However, his creators weren’t allowed to call the character gay.

Sometimes, queer-coding could simply mean making characters queer but never saying it, with comics’ most famous example perhaps being the genderfluid shapeshifter Mystique and her eventually-confirmed-wife Destiny/Irene Adler. As artist John Byrne has stated, writer Chris Claremont originally intended the couple to be the biological parents of the mutant Nightcrawler, with Mystique impregnating Destiny.

As part 3 will address more in depth, villains are often queer-coded, with Loki being a prime example. Straczynski’s/Coipel’s Lady Loki played into a toxic trans stereotype of the deviant man who pretends to be a woman in order to trick others. (As I’ve clarified elsewhere, I use the term “Lady Loki” exclusively to refer to the time Loki stole Sif’s body, and not to Loki as a woman.) Because of queer-coded villains, queer comics readers often see ourselves in villains and are deprived of seeing ourselves in heroes. However, Loki has moved progressively away from being a queer-coded villain to being an explicitly queer anti-hero.

Hopefully, with all of this in mind, it’s easier for non-LGBT+ people to understand how important it can be to see depictions of yourself in media after decades searching subtext or turning to fictional minorities like the mutants of X-Men to represent your experience in a compassionate light. Perhaps you can imagine how crushing it is to have those few concrete pieces of representation erased.

Loki, the All-Butcher (Thor Vol 5 #6, 2018)

In the case of Loki, in the time adjacent to or following Agent of Asgard, only two writers (both cis) have written on Thor solo comics: Jason Aaron and Donny Cates. Whether accidentally or deliberately, Aaron’s Thor comics (between 2014 and 2019) never depict Loki as genderfluid. Only Aaron’s Thor and Loki: The Tenth Realm (co-written with Al Ewing, author of Loki: AoA) depicts Loki as genderfluid. This suggests Aaron is at least aware of Loki being genderfluid, making his depiction of Loki as exclusively male all the more conspicuous. The one time in Aaron’s Thor run that Loki appears as a woman is in the troubling form of Lady Loki. Aaron also regularly casts Loki as the antagonist (for ex.: the King Thor miniseries), relegating him once more to the role of queer-coded villain. Outside of the MCU, Thor comics are the place readers are most likely to encounter Marvel’s interpretation of Loki, a problem emphasized by Aaron’s “War of the Realms” crossover event, which placed Asgard — and thus Loki — centerstage for comics readers. While Loki got to be an anti-hero in “War of the Realms,” he never got to be explicitly queer. Instead of celebrating one of Marvel’s most famous queer characters, the event straightwashed Loki and showed how far he could be shoved into the closet.

At time of writing, Donny Cates has written fourteen issues of Thor. He’s made a point of emphasizing Loki’s choice to cease being the God of Lies, and to take on a new role, but Cates has so far sidelined Loki’s genderfluidity. While I’m placing the brunt of my analysis in this commentary series on Loki’s genderfluidity, I do want to highlight another facet of Loki’s queer identity in passing: his bisexuality. Loki’s bisexuality was similarly made canon by Ewing in AoA, albeit remaining absent from both Aaron’s and Cates’ Thor runs. As a result, Loki has been straightwashed on multiple counts: both in terms of gender and sexual orientation.

A detail of the Pride anthology cover before and after the addition of Loki

Given the ubiquity of Disney+ Loki ads in recent months, Loki’s erasure from the Marvel’s Voices: Pride anthology is telling. The impact of queer erasure felt nowhere more apparent than the cover for MV:P, which collected over forty small cameos of Marvel’s queer characters, with a large blank space reserved for the introduction of a new queer mutant: Somnus. Loki was nowhere to be found. The anthology’s cover artist Luciano Vecchio — who also wrote and drew the comic’s introduction — had posted photos of the in-process art on his Instagram account before the comic’s publication. One of those images included Loki. As a result, it seemed Loki hadn’t simply been ignored but removed. Fans responded. At some point, Marvel playfully released a final final cover on its website, stating: “And for eagle-eyed fans, a spot reserved for one more beloved Marvel icon: the God of Mischief himself, Loki! The now fully revealed cover shows the Asgardian trickster at the side of his former Young Avengers teammate America Chavez!” This statement can’t be called an apology, or an editorial excuse, and by this point some of the harm had already been done. In addition to Loki’s temporary absence from the Somnus-free cover and Somnus “final” cover revealed on twitter, he was also on none of a multitude of variant covers, which featured many of Marvel’s most popular queer characters. On top of all of this, he was also in none of the anthology’s short stories. Because Loki is one of Marvel’s most dominant trans characters, her absence feels prominent too. In the same week that Loki came out as bisexual on Disney+, Marvel published its Loki-inclusive Pride cover as if nothing had occurred.

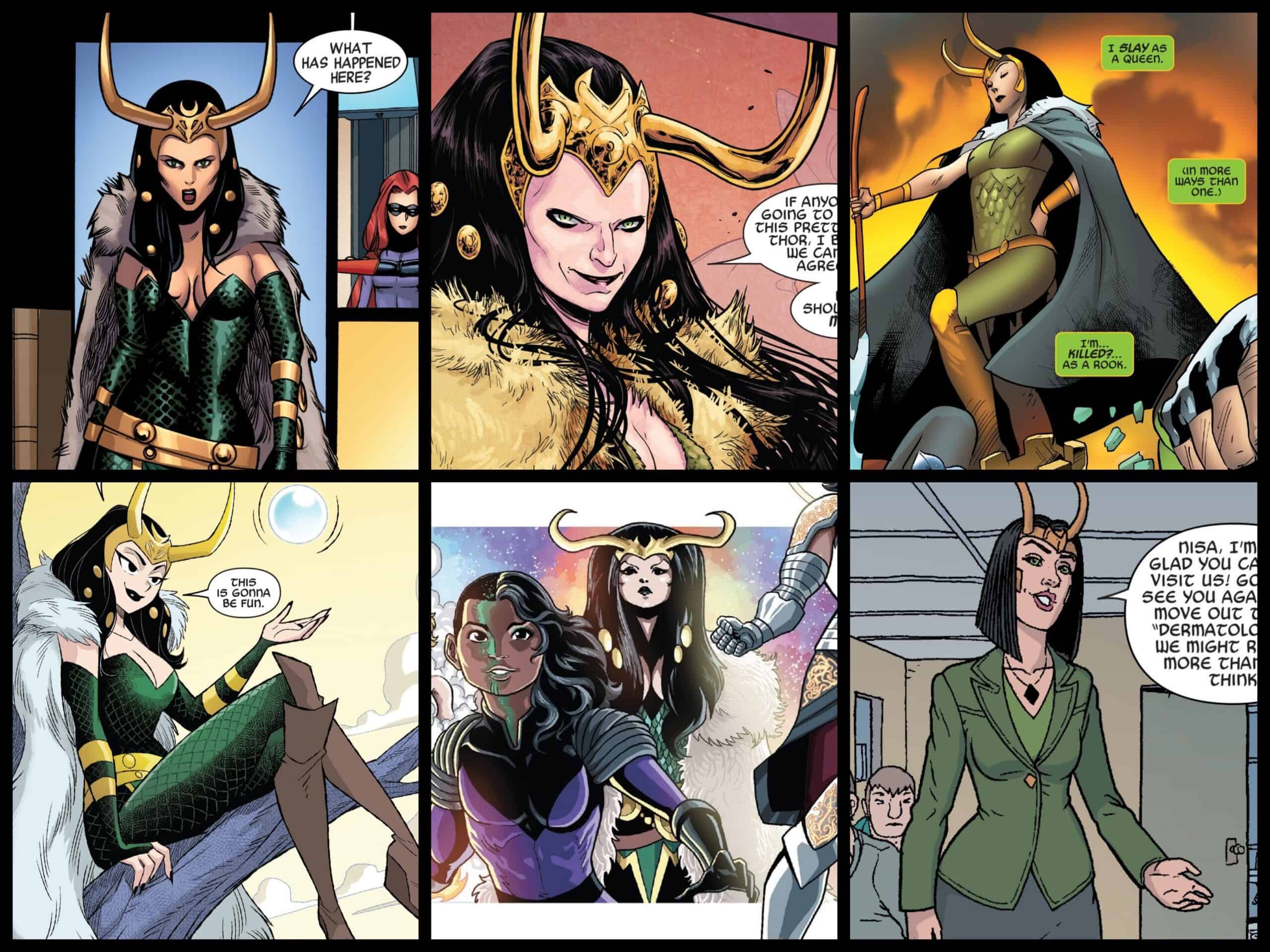

The More Things Change: Lady Loki & Character Design

In the Pride anthology, one of Loki’s appearances in the introduction — alongside some of Marvel’s other trans characters — is as a woman. However, this portrayal is undercut by the way Vecchio draws her: using Coipel’s Lady Loki design. Vecchio is far from alone in referencing this design, but its appearance in a Pride anthology is incredibly galling, as it encourages readers to recall a transphobic comic storyline. In the five comics (not counting MV:P) which have depicted Loki as a woman in the timeframe adjacent to or following Agent of Asgard (and Thor and Loki: The Tenth Realm), all but one have used Coipel’s design. The outlier is 2016’s Vote Loki miniseries, which sees Loki in a skirt/suit. Perhaps the most disappointing reemergence of Coipel’s design is in Thor & Loki: Double Trouble, a 2021 miniseries written by Mariko Tamaki with art by Gurihiru. A comic aimed at kids, it introduces children to a harmful trans stereotype and misses the opportunity to offer children positive representations of trans people. At time of writing, the final issue hasn’t been published, and while I hope Loki’s gender is addressed in a more positive light, what has already happened still matters.

While any and all of these books could have followed Lee Garbett’s approach to Loki, drawing her outfit as fundamentally the same regardless of gender, they perpetuate transphobia instead. While artists may simply be turning to the design because it’s become iconic, things become “ iconic by being reinforced. Good imagery has every opportunity to become just as iconic when artists choose to use it instead. If the issue is simply a question of “How else would readers know this woman is Loki?”, I return once again to Garbett’s design, which fundamentally only changed the body of the person wearing the outfit, rather than the outfit itself. The comics could also choose to reflect how non-shapeshifting genderfluid people (aka real genderfluid people) may change clothes to reflect an internal sense of gender. It’s also possible for our gender to change and appearance remain the same. However, rather than any of these potential approaches, artists return to the familiar — and both Loki and real trans people are the worse for it.

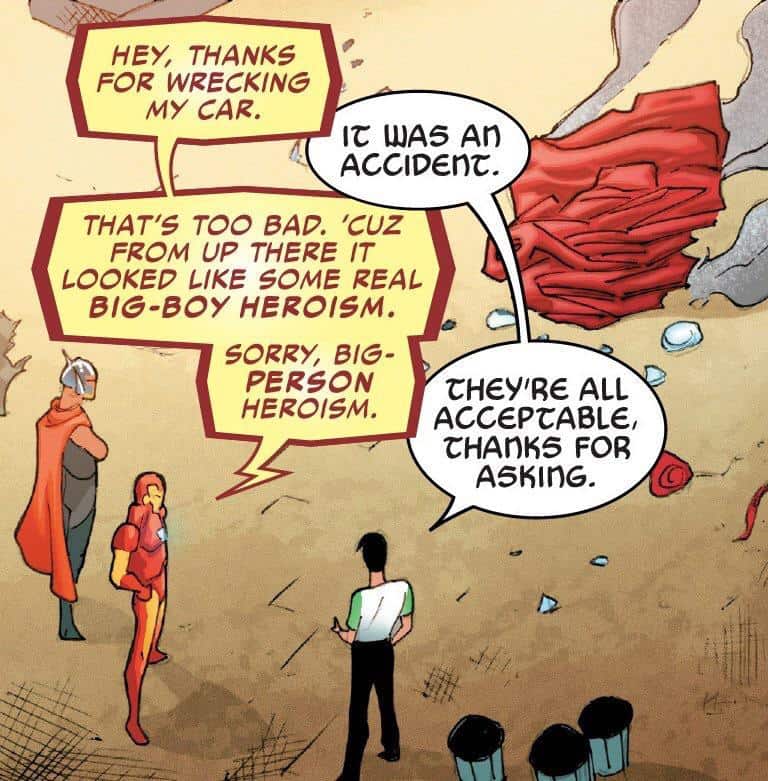

Unbeatable Squirrel-Girl #28

“All of Us, Alone Together”: Genderfluidity and Loki, God of Outcasts

Amidst the erasure and the problematic character design, there are actually a few wonderful moments where Loki’s genderfluidity continues to appear in the comics. Loki’s genderfluidity was mentioned, for example, in a panel of Unbeatable Squirrel-Girl #27 (2018). Written by Ryan North, this is actually the only concrete use of the word “genderfluid” in reference to Loki — by Loki — within the comics. Loki was also a woman for the entirety of the 2015 A-Force series by G. Willow Wilson and Marguerite Bennett, though regrettably artist Jorge Molina used the Lady Loki character design. Loki also started the story as a protective mother-figure, but ultimately ended up being a sympathetic villain. In 2016’s Vote Loki (a comic in which Loki runs for President of the USA), Loki was a woman for only two pages, but fortunately not in the Lady Loki outfit.

One of the most notable examples of a comic that did continue to represent Loki as genderfluid — and often well — is the short-lived 2019 “ongoing” Loki series written by Daniel Kibblesmith. While Loki doesn’t shapeshift in those five issues, Kibblesmith stated in his final letter when the comic was cancelled that he had always planned on showing Loki as “the moon goddess” again. Kibblesmith is also partially responsible for the creation of a pair of trans superheroes that were widely panned (for good reason) by the trans community. While Marvel chose not to publish that book, it sheds some doubt on how Kibblesmith might have approached a female Loki had Loki’s series not been canceled.

Loki (2019) #4

That said, Kibblesmith still did a couple of significant things that made me sad to see the comic go. First off, Tony Stark says something gendered and immediately apologizes, to which Loki responds by clarifying that all forms of gendered address are fine. As with Odin in AoA and Tenth Realm, I appreciate having a comic bluntly state “even an infamous jerk can get this right.” It’s the sort of moment trans people need. It’s a crucial acknowledgment that a genderfluid person is still genderfluid even if nothing about how they express their gender to others seems to change.

In addition to this small moment, Kibblesmith did something much larger and more significant: gave Loki a new title — God of Outcasts. When taking the title, Loki tells his audience: “A lie is a story, yes. But I remember the first lie I ever told. Which means before I was a liar, I was something else. Cast out. Out of kingdoms. Families. Universes. Again. And again. And again. I am Loki. God of Outcasts. They see themselves in me, and I in them. All of us, alone together.” While that might be a bit on the nose, this description aligns the newer and more heroic Loki with marginalized groups (Loki himself being trans, bisexual, and a member of an marginalized (fantasy) race — Frost Giants). That act of renaming places Loki not only as part of but protective of those whom society has ostracized and oppressed. While Loki is firmly in my own head as the God of Stories, I also wish the God of Outcasts were more accepted, acknowledged, and explored in the comics. In many senses, Loki — both mythologically and in the comics — represents liminality, the space between binaries. As both a Frost Giant and member of the Aesir, he becomes simultaneously neither: a giant among the gods, but a god among the giants. And even if the newest Loki desires to be a hero, he isn’t as heroic as his brother Thor — and he isn’t truly a villain. Tricksters, even trickster heroes, lie firmly outside of yet another binary. As a result of his many liminal identities, Loki exists finds himself an outsider, an exile, and an outcast. And rather than reject that, he embraces it. For many liminal people facing marginalization and oppression, acceptance and equity are necessities, but “assimilation” is a very different animal. For example, the only way a society with a binary system of gender can assimilate genderfluid people (and nonbinary people more broadly) is to force us into a binary gender. Yet, simultaneously, to be liminal without acceptance or equity can be to face both individual and systemic violence. Over all, I think Kibblesmith goes somewhere deeper than “here’s to the misfits” and hits on why a lot of people are drawn to Loki as a character. Loki doesn’t exactly fit, and trying to fit for marginalized people often simply leads to frustration: to denying some part of yourself. While being an outcast is ultimately bleak, and acceptance-without-assimilation is the goal, aligning Loki textually with marginalized people is incredibly important to emphasize and not (as many comics have done) erase.

New Gods and Goddesses of Stories: Beyond Loki

In the coming years, with Marvel focusing more on Loki than ever, I have hopes for better Loki stories that embrace his gender and her sexual orientation in its fullest. I really do. But I also hope for something better than Loki — beyond Loki. To put it bluntly: I deserve better than my favorite fictional character. There are still glaring, massive flaws to Loki. Often, trans people are depicted as evil tricksters bent on harm. And Loki? Loki was Marvel’s God of Evil for a while, and remains a trickster-hero for both better and worse.

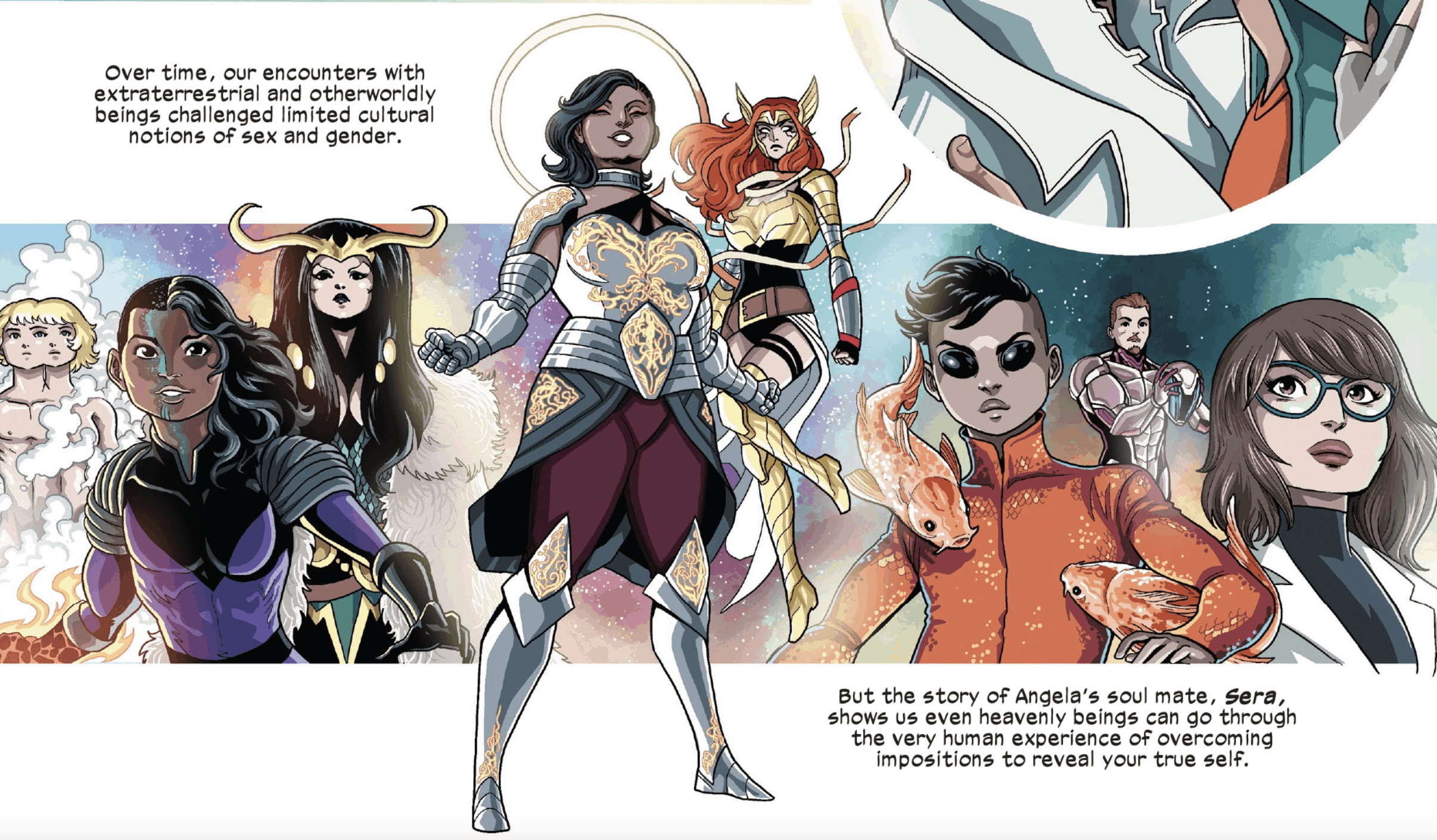

from the introduction to Marvel’s Voices: Pride (2021)

For decades, Marvel’s cast of trans characters has been incredibly limited. While they may no longer be forbidden by the CCA, trans readers are often still stuck seeing ourselves mostly in aliens, shapeshifters, and deities: the non-human. Loki, as much as I love her, is all three. While it’s easy to argue that being equated with deities makes us better than human, it exiles us from humanity. And shapeshifting turns trans-ness into a sort of strange superpower. As cool as I think I am, and as much as I’d like that superpower, Marvel needs heroes who are trans — not heroes with the power of transness. This trend of aliens/deities/shapeshifters is easily noticeable in the “trans” section of the Pride anthology introduction, which includes Cloud (Marvel’s first canonically trans character, a shapeshifting nebula), Xavin (a shapeshifting skrull who hasn’t been in a comic in roughly a decade), Sera (angelic girlfriend of Loki’s long-lost-sister Angela), and Loki. The only other trans characters Vecchio includes in the introduction are Koi Boi, Charlene McGowan, and Trace. All are relatively minor. Vecchio’s narration from an in-universe narrator, whether on purpose or not, seems to drive home this problem: “Over time, our encounters with extraterrestrial beings and species challenged limited notions of sex and gender.” However, Vecchio also de-historicizes the way trans people have existed for hundreds of years without alien intervention and that colonialist “limited notions of sex and gender” intentionally erased trans people across the world. Those are the stories that need to be told, that need space to be shared by trans storytellers allowed to tell them.

We need trans characters and creators who are BIPOC, disabled, and non-heterosexual. There are so many trans people who deserve to see themselves and tell their stories. We need more trans creators allowed to tell their stories — our stories — and other stories too. We need a societal transformation that goes beyond Pride Month, a society that breaks down and transforms its perceptions of us rather than simply breaking us. We need the ability to tell our own stories instead of simply praying the next cis author will write something that isn’t erasing, troubling, or traumatic.

Loki: Agent of Asgard #16 (Ewing, Garbett, et al.)

At the end of the day, what Marvel does with its characters is its prerogative, but I hope and pray that Marvel begins to embrace a wider variety of both trans characters and trans creators. Loki might be the God of Outcasts now, but there is no better time than the present for trans writers and artists to take on the mantle of God and Goddess of Stories. As Loki demonstrates so beautifully, to control one’s own story can mean to transform both yourself and the world around you. Stories don’t have to reinforce bigotry: they can also overwhelmingly be a force that encourages change. Stealing once more from Loki’s Agent of Asgard monologue: “You can’t kill the stories. Lots survived and lots will.” Let’s tell some good ones.

If you’re curious about how Marvel does at depicting Loki’s genderfluidity and bisexuality in the Disney+ show, and how it relates not just to the comics but to a lengthy history of film censorship, I encourage you to return for the third and final part of this series, which will be published in the weeks following the show’s conclusion.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this and want to support me/my writing by “buying me a coffee,” you can do so at my Ko-Fi here.

Please also consider donating to somewhere like Trans Lifeline, Transgender Law Center, or The National Center for Transgender Equality.