There Is Nothing Left to Say (On The Invisibles)

How the Helga Get in Here?

by Travis Hedge Coke

“Viltu nú taka helga skírn?” (“Do you want to be baptized now?”)

– The Story of Norna-Gest, trans. Nora Kershaw

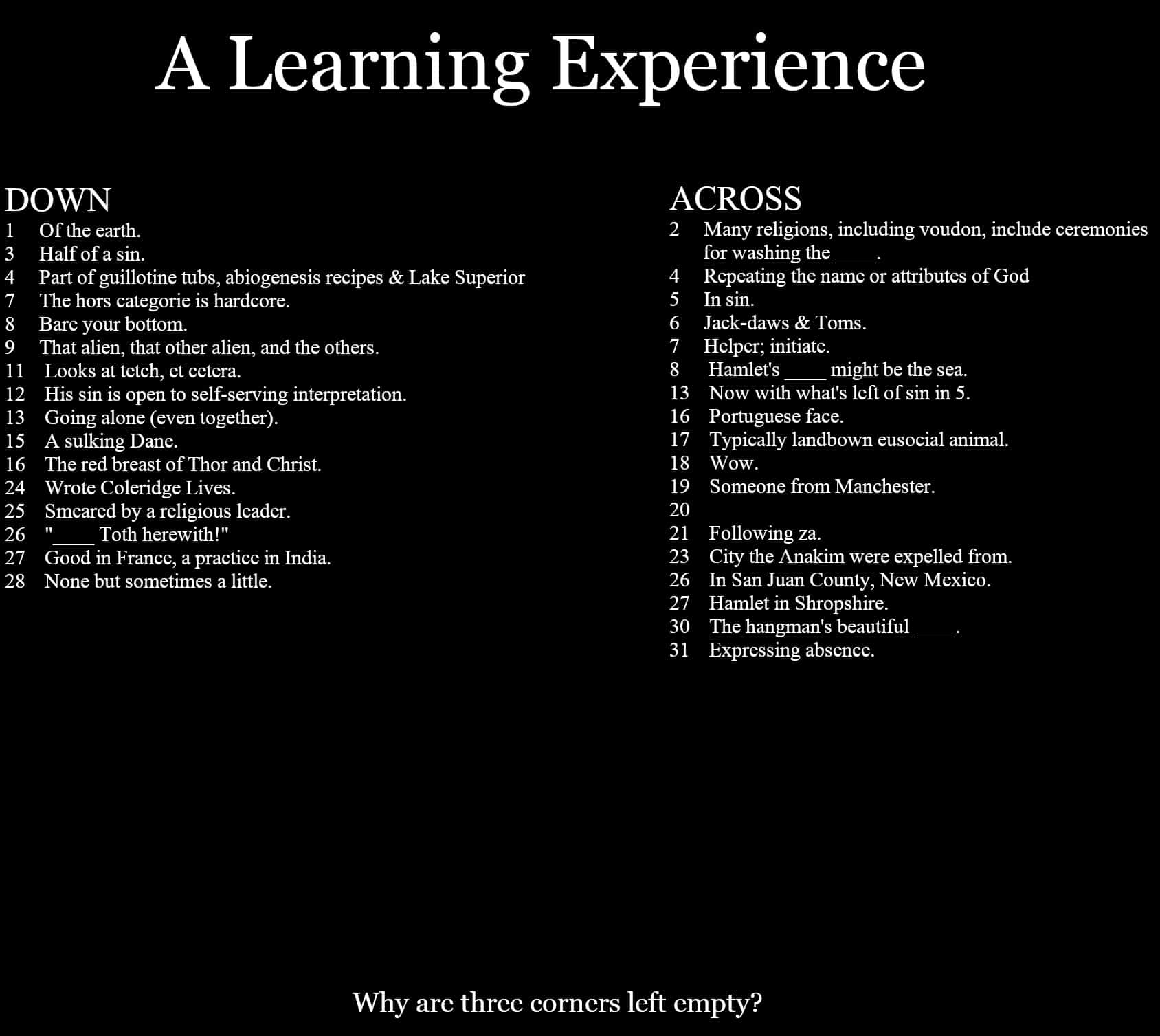

O. U. I. J. A. B. I. R. D.

Helga, of The Invisibles, looks like somebody.

Michael Chekhov says, “The moment you are not alive on stage, you are dead.”

Two eagles kill a pregnant rabbit in Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, and it is misinterpreted. Same thing happens in Masked and Anonymous with Bob Dylan and Cheech Marin. They misinterpret it, but they might be being facetious. Maybe birds can be bad communicators. Or, the language isn’t there.

Olga Tannen was my friend. She once looked on beachside dancers through my lens.

I am always amused by artists, especially, referring to figures who, by their face or hair or style or posture are someone instead of stock. I experience a minor anxiety, because, aren’t we all? Frank Miller has discussed it in light of seeing creations performed by living actors. It is how Chris Claremont explains the genesis of his Holocaust-survivor version of Magneto, based on his youthful encounter with the way Neal Adams drew Magneto unmasked in the late 1960s. It is what makes Pygmalion, Pygmalion; Galatea, Galatea.

There is no shallow end to the pool of life and the “CliffsNotes version” is not study, just a study guide. That is why There Is Nothing Left to Say is not chapter guides or timelines. Helga does not live in a The Invisibles which is planned.

All times are one.

You can drown in a puddle. You can swim in your dreams. The Invisibles is live like language. You know when you need to dive to the bottom. You know when you want to go up for air.

“The valkyrie prided herself on her wisdom,” as Nora Kershaw translates the fragment called, Hrafnsmál (or, Raven Song), “And the warlike maid took no pleasure in men, for she knew the language of birds. With white throat and sparkling eyes she greeted the skull picker of Hymir as he sat on a jutting ledge of rock.”

Bees hath white throat. Be sheath, White Throat.

Saint Helga, or Saint Olga, was a widowed monarch who appeared to accept a marriage proposal from her husband’s murderer, only to have her people drop him in a trench, along with his entourage, so they could be buried alive.

Olga Tannen, which could be Helga’s birth name, as an equivalence, in Thelemic Qabalah, to “princess”, which Saint Olga was, and “magic diary”, which Helga fabricates. And “politics”, “great rite”, “intrigue”, and “Mercury”, which Helga is.

Magic name, amen.

Saint Olga is the “equal to the Apostles”. Helga is often despised – for some do despise her – for being treated, in Volume Three of The Invisibles as equal in significance and panel-presence as characters we had followed for dozens of issues before her first appearance.

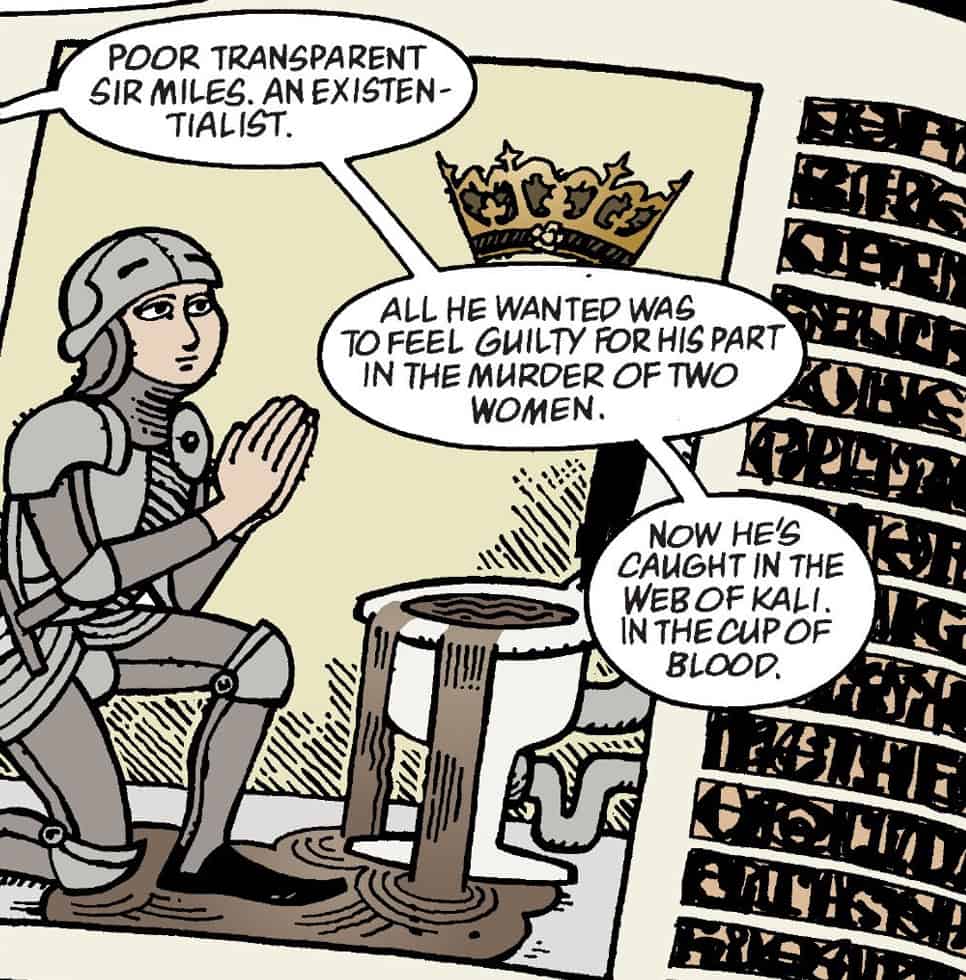

Who is this arid bijou interloper who was only meant to be a background girlfriend filling a seat and took the comic on a media studies, high bullshit, grimoire from the toilet ride?

What rite hath she to be?! Who is this insatiable creature with a love for the dead?

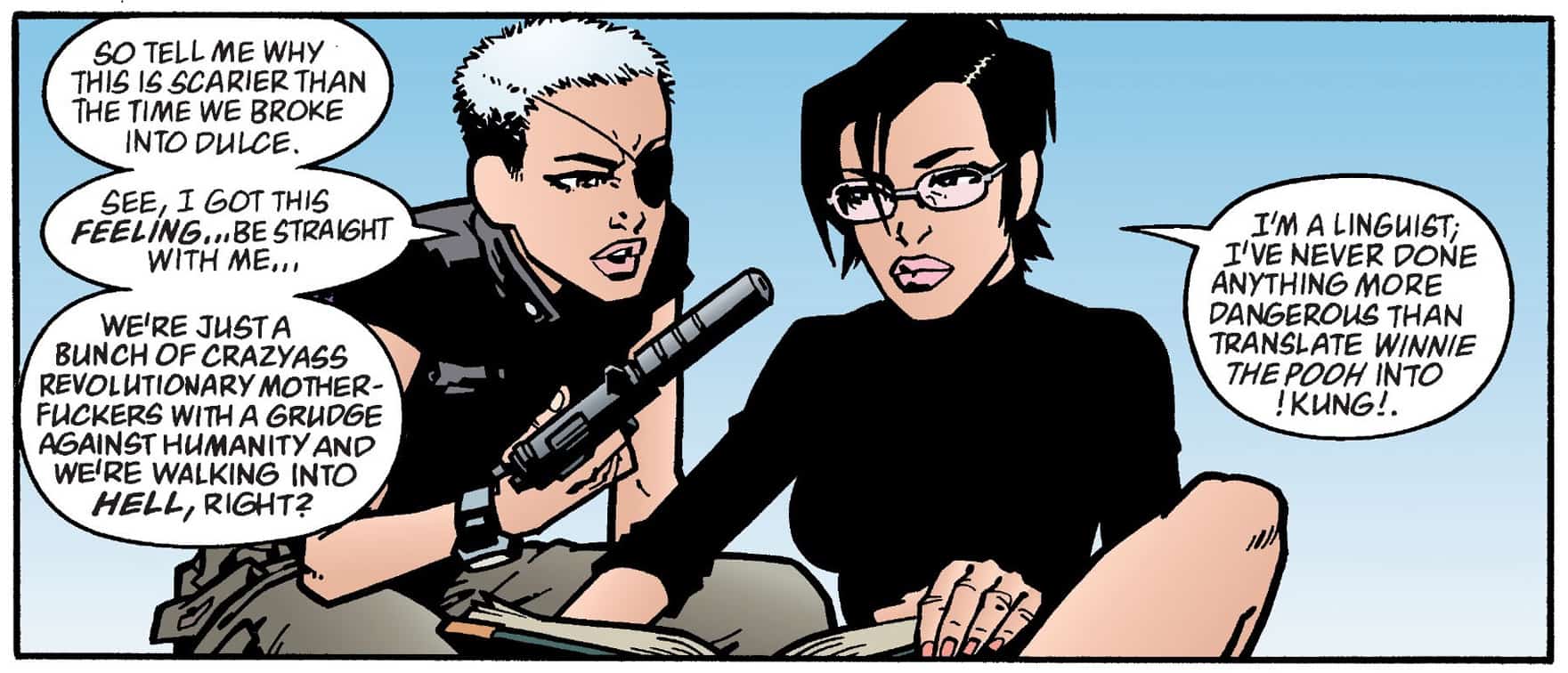

Helga the perpetual liar, a collagist, gag artist, who performs lectio divina in impatience, and appears to live in a constant state of manicured calm and improvisation for most of, if not all Volume Three. Described by some critics as “immature”, an overacting teenager, “a distraction”, Helga only joins the main plot of the volume, and participates at the highest levels, because she looked like somebody. She caught a moment in a writer’s eye. The artist got her wrong right, and she became.

All hypnosis is autohypnosis. (Hypnosis by other people would be marketing.) The best times to practice lucid dreaming whilst awake are while wandering alone on nearly empty streets and while using the toilet with nothing nearby to read, watch, or listen to.

Practicing pure psychic automatism – the generation of ideas and relations without concern for aesthetic or political context – has its benefits but opens you to criticism if you let your automatic generations be known.

It has been suggested by pencilers and the writer, that some early Invisibles came too soon or in the wrong form.

The opening arcs of Volume One are heavy on exposition, dense, but dense with information that savvier audiences will already have, and lionize the most brutal and defensive of their characters. The comic opens with our hero a violent, bitter, self-righteous, but fun enough, kid. And while the next arc, a time travel lark, lightens him up and costs him a fingertip, the mission seems to be that the more sensible or caring people we encounter are to be left for eventual death. But the Marquis De Sade is so important he has to be saved past death to be an architect for our necessary future. This all pans out, but the anxiousness we can have reading this the first time!

Down and Out in Heaven and Hell becomes a comfort recapitulation. Seen from the perspective of Volume Three and Helga, those early stories splinter, refract in recombination.

The part of a guitar string close to the the bridge, the nut, under the finger or slide against the fret, cannot produce the note of the loosened, but tuned freer string. All one string, each, and in variations, purposes, productions. We can play at the nut. Bridge. We can slap bass.

Circa 2022, I begin to think of The Invisibles as an openclose circuit, an example of the subgenre, Sentinemental Nonsense. Piece treaty. Unser Helgas Leben (Kabeljau German and cod germaine can really swim; “Here you can not only inflect Hiawatha but also all German nouns”).

By Volume Three and Helga, instead of two page sequences explaining a principle, or five-step hero’s journey beats, boiler plate cosmic awakening, everything flows in invisible rivulets, flows as rivers in the sea in the ocean over the Earth, and it flows because it is all cut up and mainlined and we were started tripping an hour ago this is the come down. And, then, in The Invisible Kingdom, as if mirroring the Volume One story which shares its issue numbers, produces again those two-page explications, the jungian backbeat and Malory King Arthur.

Helga defeats and detourns, detours and turns round the enemy by posing, lying, by creating spur of the moment elaborate art pieces and saying things so absurd they cannot be functionally countered while remaining annoying to anyone too stick in the mud to simply let them go. Our lady of shall it and shall’n’t.

Typical warbler. White throat. Astonishing Helga who can smell sin, or says she can. Lying saint. Girl knight. Shining woman.

Firewalls are stepping stones if we make ourselves big.

By the time of Helga, the early arcs, anything that was not working, as been repurposed into something that now will.

Abase Toth herewith! Olga Tannen, you art school weirdo.

Now. Will.

Helga thrives through a hagiographic universe. As Ragged Robin – as much as any or everyone – she can write in it.

With peck of pen and flap of bond, Helga’s lances and images change truth. Her activities are so flared and fun, articulate but absurd, she dares conflict, begs debate, and a begged debate is a rigged debate. Olga Tannen makes the grade!

Helga can put me in mind of Nora Kershaw, a philologist and translator who ran literary salons and lectured at St Andrews, without having any other connections than those I connect. I connect the dots. I connote the dots. I dot the damn dots, helga dotter.

The strange breast milk of St. Christina Mirabilis.

Language is passing weird and mostly in our heads and pens, our mouths and humors.

The extra mouth of Deganawida.

Words are in what we do, and if you are a collagist, in what you glue. Der Helgas Leben. Hiawatha is from Ayenwatha. That is transliteration, still. Encumbrance can speed success.

As we will quote again, in chapter 3.06, “The writer would especially ask the literary reader, who is competent to discriminate between a narrative of facts and a work of fiction, to consider whether it is probable, or even possible, that this work can be entirely the product of the writer’s own brain.”

Circa 2006, my friend sends me a feature-length pornographic satire of people and places we know – plausibly deniable as generic art school, but we know. She tells me the director is an asshole. It is the largest file anyone has ever sent me up to that time.

A sometime DJ, my friend who pronounces “junglist”, like “Karl Jung list”, once borrowed and subsequently lost my Transmetropolitan-style prescription glasses at a beach rave she emceed, and can roll her eyes for a century while saying, “lifestyle”. She used to tell people, when she felt like it, that her name was Olga Tannen.

Some concerts, it is popular – or was – to shout out for Helga, to call to her, whoever she is. Some answer back, “Helga is dead!” Except, they do it in German, because it is a German thing.

Spare as sparrows. Passing as passerines. Pre-Helga Invisibles has a careful hermetic structure of teacher and student, lessons by example, or direct textual confrontations with the epistemological nature of realness. Helga has an alchemical style, obscuring as she gives. The comic, itself, ceases to have breaks and waves, and becomes the death fields in which a maiden can rest and listen to raven talk.

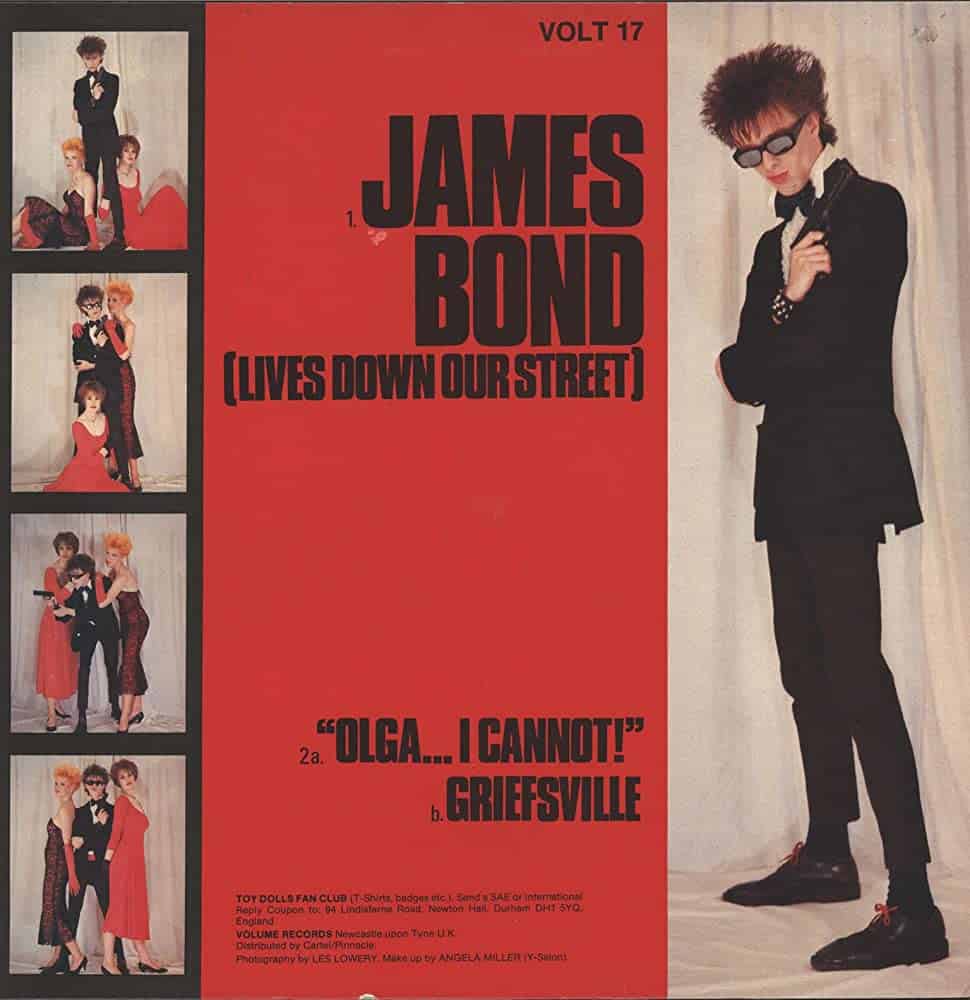

Olga plays a yellow Fender Telecaster as the frontman for the Toy Dolls, who performed a memorable number of novelty songs in a new style, as well as Olga… I Cannot! and James Bond (Lives Down Our Street). This is a different Olga, but also, I do not think it is.

Now! Will!

Helga ist tot!

Helga is taught.

*******

NEXT: Boy Our Embarrassment

And previously:

- Prologue/Series Bible

- Chapter One: I Was a Librarian’s Assistant (Pt. 1)

- Chapter Two: I Was a Librarian’s Assistant (Pt. 2)

- Chapter Three: Robin Roundabout

Nothing in There is Nothing Left to Say (On The Invisibles) is guaranteed factually correct, in part or in toto, nor aroused or recommended as ethically or metaphysically sound, and the same is true of the following recommendations we hope will nonetheless be illuminating to you, our most discriminating audience.

Morrison, Grant. The Invisibles. Jill Thompson, Chris Weston, et al. DC Comics. 1994-2000.

Ten Years of Toys, Toy Dolls

Anglo-Saxon and Norse Poems Book by Nora Kershaw Chadwick

Chopra at 32