Welcome to Image30, Comic Watch’s celebration of three decades of Image Comics! Throughout 2022, each week we’ll take a look back, chronologically, at the comics that built the publisher into the powerhouse it is today, and changed comics forever! In doing so, it’s our hope to paint a clear and definitive picture from a finished product perspective how the company originated, grew, evolved, and changed into the diverse juggernaut it is today.

Image30 Chapter 13:

Gen 13*

As with any decade, the 1990s had its own particular zeitgeist, vagaries, trends, and otherwise “things that we thought were cool but look back on now and laugh/roll our eyes/cringe.” Comics aren’t immune to this, acting as both an amplifier for cultural touchstones but also pushing those trends forward throughout the media until the Next Hot Thing comes along and suddenly, what’s determined as “cool” is a relic of the past (cue Grandpa Simpson “I used to be with it, but then they changed what ‘it’ was” meme). Such is the case with WildStorm’s Gen 13, perhaps the epitome of ’90s-ness that struck at exactly the right time to actively be the embodiment of what it meant to be “cool” in the mid-’90s.

That’s not meant to mock it, or its creators. Far from it. There’s a fair bit of luck concerned with capturing the moment, and Jim Lee, Brandon Choi, and then-rookie sensation artist J. Scott Campbell had the absolute blindest of luck to chance upon lightning in a bottle, at least for that moment in time. But there’s also a canniness involved – a working knowledge of what fans want, what the culture is feeding off of, and how those two things intertwine to satiate the masses. This is how pop culture trends are born, and it’s into that particularly incestuous social more that Gen 13 was born.

Monetizing teen purchasing power was nothing new, and could be traced back to the youngest Baby Boomers being targeted as a demographic that could be catered to back in the 1950s. The increasingly ubiquitous medium known as “television” helped with that, as did the rapid rise of rock ‘n’ roll as a cultural force and the James Dean archetypical rebel without a cause (both on film and in public consciousness). Teens, suddenly, were seen as a marketing prize to be sought: after all, who’s more frivolous and less responsible with their money than teenagers? Cynical and calculating, sure, but the trend became part of both pop culture and marketing fabric from that point on.

The ’90s were no different: grunge culture was ascendant, and everything it entailed: skateboarding, flannel, non-self-indulgent moping, self-indulgent moping, and, most importantly, a particularly Generation X-style disdain for anything that was trendy beforehand. All youth tends toward a distrust of authority; Generation X elevated that into an artform. It was part of their cultural identity, and in this particular case, “authority” extended to “anything that was popular before us.” That cynical ethos extended to Gen 13, at least foundationally.

Of course, it could also be said that it extended to the entire Image Comics raison d’etre, too.

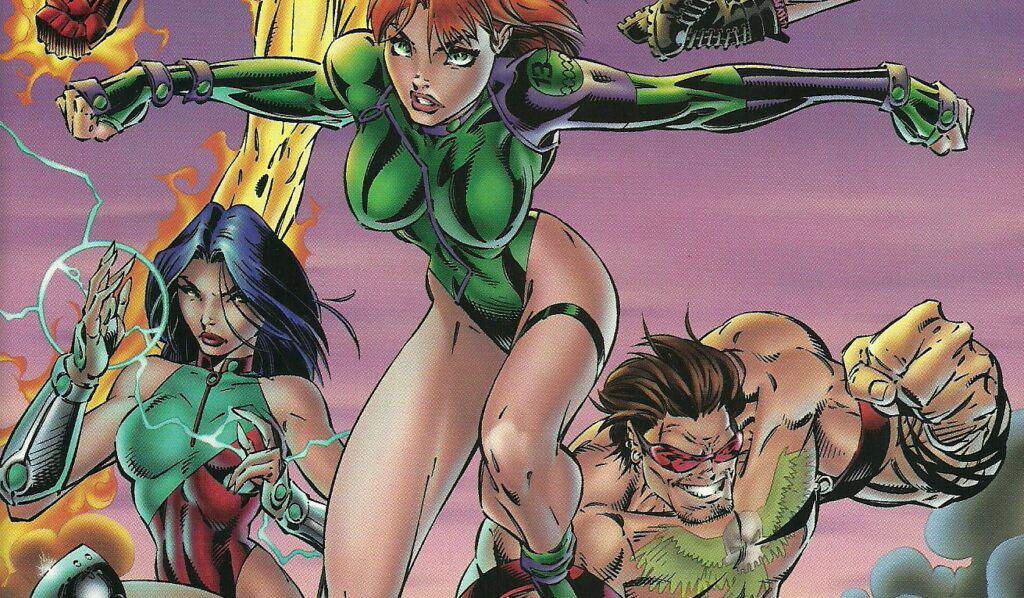

But conversely, Gen 13 isn’t a cynical comic when it comes to the actual story execution. It’s light and bubbly, not particularly concerned with telling deep and dire stories with world-changing stakes; it deliberately leans into Campbell’s cheesecake, buoyantly kinetic art. Fairchild, Rainmaker, Burnout, Freechild, and Grunge (yes, the perhaps ultimate ’90s comic absolutely costarred a character named Grunge, which is akin to a late ’70s comic featuring somebody named Disco) were products of a ubiquitous, clandestine government secret experiment on “gen-active” teens, who were eventually revealed to be the children of various members of WildStorm’s Team 7 characters (who themselves were, somewhat confusingly, designated Gen 12). The kids went rogue with their mentor John Lynch, became a team under his training and watchful eye, and got into shenanigans from there. Gen 13 was part of Jim Lee’s deliberate effort to turn WildStorm into an interconnected universe not dissimilar to Silver Age Marvel; the book stood on its own but had undeniable tendrils in the ever-increasingly dense history being written across a multitude of books like the aforementioned Team 7, WildC.A.T.s, StormWatch, Backlash, Deathblow, Grifter, Wetworks, et al.

Originally debuting in Deathmate Black in 1993, the team graduated to miniseries status in 1994 and instantly became the Next Hot Thing. The kids couldn’t get enough of ’em! They were teens, but they were marketed as “our” teens, not “our parents’ teens” a la the Teen Titans or New Mutants. (As an aside, by late 1994 Marvel was developing its latest X-spinoff Generation X to tap into Gen 13‘s popularity. The two teams would eventually meet via intercompany crossover a few years later.) The initial five-issue miniseries sold like wildfire, and an ongoing series from there was a no-brainer, debuting in early 1995.

It wasn’t just that the team’s designs were cool, it was that, in true ’90s-Image form, they looked cool doing… well, just about anything. Campbell is perhaps derided for his cheesecake tendencies today, but at the height of his popularity in 1995-96ish, he could do no wrong, producing striking cover after striking cover:

But perhaps inevitably, it’s impossible to detangle Gen 13 from the inherently exploitative nature of Campbell’s art, which is where that original cynicism comes back into play. Gen 13 was a comic marketed to horny male teenagers, about horny teenagers, in just about the most salacious way possible. This was during another particularly ’90s trend, the Bad Girls era, in which impossibly busty and curvaceous characters like Lady Death, Purgatori, Lady Rawhide, Shi, and Vampirella were unabashedly sold to drooling teen male fans in the most deliberately hypersexualized ways possible just short of full-blown pornography. Campbell never took it as far as some of his contemporaries, but he didn’t shy away from the trends of the day, either:

No, Grunge. This isn’t okay.

It was all seen in innocent fun in the ’90s, though, one of the last eras where the leering male gaze was normalized as “okay” without any consequences or second thought. This was also a time when superhero comics were very, very rarely marketed toward female readers, and if a few gurls might get turned off by cheesecake, what’s the big deal, right?

Oof.

As with any flash in the pan, though, Gen 13‘s moment left as quickly as it came. Campbell bolted the book after twenty (erratically-shipping) issues to launch Danger Girl, an even more sex-obsessed comic from WildStorm’s then-burgeoning Cliffhanger line, and others stepped up to the plate to try to take a swing at figuring out some new ways to keep Gen 13 relevant. John Arcudi and Gary Frank’s more humorous, freewheeling take came closest, generating some decent critical buzz, but sales continued to spiral and the book was eventually mercy-killed in 2002 with perhaps the ultimate cynical move: the team was seemingly killed off by a six-megaton bomb with issue seventy-six, with only Fairchild remaining. Ouch. Two subsequent attempts to reboot the comic in the ’00s came and went without much fanfare whatsoever (even with powerhouse Gail Simone writing at one point!). The team, along with the rest of the WildStorm universe, was absorbed into the DCU proper post-New 52 and only Fairchild has made sporadic appearances since. Quite a comedown for a comic that was once such a force within the comics world, but then, that’s what often happens to pop cultural curios that are tied to a specific moment in time once that moment passes. And that’s what happened to Gen 13. But for a brief, shining moment, it was the comic everyone was talking about.

Most comics only wish to be that lucky.

Jim Lee would of course go on to sell WildStorm to DC in 1998, and now acts as their Chief Creative Officer who occasionally draws awesome covers. WildStorm itself would exist as a DC imprint until the 2011, when as mentioned above it was brought into the DCU proper post-Flashpoint. Brandon Choi has continued quietly working in comics, though his career has largely receded to the background since his primary partner, Jim Lee, has become embroiled in the more business-focused side of DC. J. Scott Campbell retains popularity as a variant cover artist, sticking to his stock-in-trade as a cheesecake artist. He knows what he does best and sticks to it, which earns him the enmity of some more progressive segments of modern fandom. But he’s in demand and working regularly, so clearly, he’s done something right for himself. And if Gen 13 is the legacy that lead to him being able to comfortably crank out covers and not much else…? He’s probably pretty satisfied by that.

NEXT: Image starts to shed its own image and moves toward a new dawn as Kurt Busiek, Brent Anderson, and Alex Ross’s ASTRO CITY makes comics history!

For Chapter 1: Youngblood, click here.

For Chapter 3: Savage Dragon: click here.

For Chapter 5: ShadowHawk, click here.

For Chapter 8: 1963, click here.

For Chapter 9: The Maxx, click here.

For Chapter 11: StormWatch, click here.

For Chapter 12: Spawn/Batman, click here.

*It was NOT planned that Chapter 13 be about Gen 13. Serendipitous accident!