Welcome to Image30, Comic Watch’s celebration of three decades of Image Comics! Throughout 2022, each week we’ll take a look back, chronologically, at the comics that built the publisher into the powerhouse it is today, and changed comics forever! In doing so, it’s our hope to paint a clear and definitive picture from a finished product perspective how the company originated, grew, evolved, and changed into the diverse juggernaut it is today.

Image30 Chapter 17:

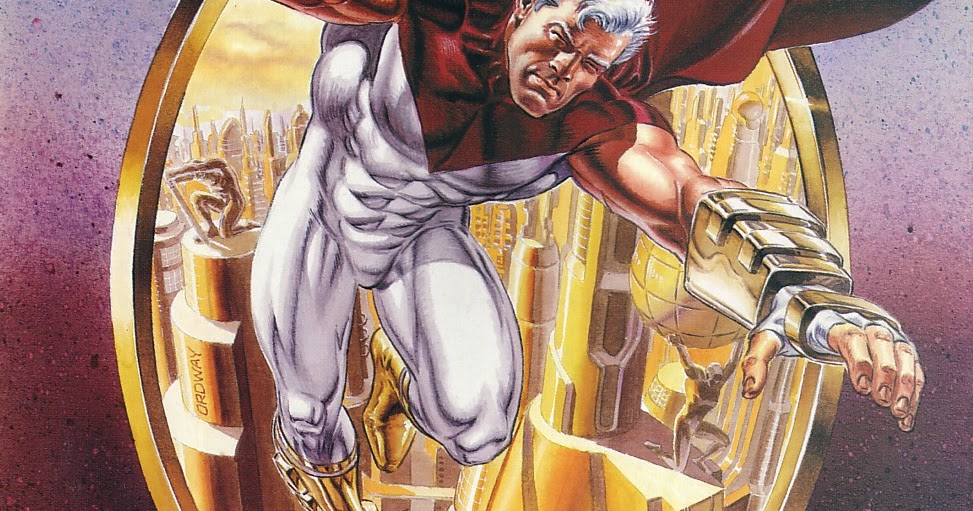

Alan Moore’s Supreme

As recounted last week, 1996 was a tumultuous year behind the scenes at Image, reaching crescendo in 1997 with the ouster of founding father, and poster child for the company’s early-to-mid-’90s antiestablishment attitude, Rob Liefeld. It wasn’t just Liefeld’s eventual dismissal from the company that shook things up. Earlier in 1996, Marvel made one of the most baffling humble-pie-eating moments of the entire decade, and its reverberations would shake Image to its core.

As the ’90s wore on, Marvel’s fortunes had continued to plummet outside of the various X-Men books, as upstart companies like Image and Valiant ate further and further into their audience, causing sharp declines in readership and sales figures. The old guard at Marvel wasn’t sure what to do with most any property that wasn’t X-Men; the classic mold heroes the company had been founded on were looking anachronistic and creaky compared to What the Kids Wanted, i.e. more violent, darker antiheroes like Spawn, Savage Dragon, WildCATs – really, pretty much any Image book up to that point. Marvel flailed, and tried increasingly gimmicky approaches to gin readers’ interest. Putting Captain America in a bulky armor suit didn’t work and reeked of laughable desperation; turning Iron Man evil and replacing him with his teenage self was met with collective resentment; trying to turn the Avengers into an X-Men-style soap opera flopped; having Thor lose his shirt and gain spiky shoulder pads and a head gear went mostly unnoticed.

Nothing was working, so in what was without a doubt the desperation move absolutely nobody could have foreseen, Marvel threw up the white flag, and did the unthinkable: they invited Jim Lee and Rob Liefeld, who had very publicly walked out on them five years prior to cofound the rival company currently kicking their butts back to the fold. The deal was jaw-dropping: Marvel outsourced the Avengers, Fantastic Four, Captain America, and Iron Man to WildStorm and Extreme Studios, respectively, for a year, to re-imagine and do with what they will to reignite excitement about Marvel’s non-mutant superheroes. The four books were segmented off into their own little reality, started fresh with new first issues, new continuities, and new costumes. Lee and WildStorm handled the FF and Iron Man; Extreme and Liefeld took Avengers and Cap. The terms of the deal was for one year; with an option to release either Lee or Liefeld from their contract at the six month mark if certain sales figures, standards and practices, and regular deadlines weren’t met. All four books launched in September, 1996.

Old school Marvel fans were aghast made quick with the pearl-clutching: These young punks were going to RUIN their heroes! The newer generation of fans was skeptical, but curious: I don’t care about these dad comics characters, but Youngblood is cool, so why not give it a shot? The results were, perhaps inevitably, a mixed bag: sales were brisk, at least initially, and the pictures were pretty. The FF in particular benefited from being slapped with an updated coat of paint; the book had been trapped in a morass of questionable storytelling quality for awhile and was failing to evolve with the times. Iron Man, too, as redesigned by Whilce Portacio, got a sleeker, then-modern look that was far more techno-informed than any previous iteration (hey kids, this internet thing was gonna be huge). It was clear that WildStorm and Jim Lee knew the homework, and were turning the assignments in on time, and their efforts were clicking with fans. But as for the two Liefeld books…

Captain America and Avengers were perhaps doomed to fail, though not for lack of trying. Liefeld and Extreme Studios’ habitually missed deadlines had long dogged them both, and their inability to function in what Marvel deemed a professional manner behind the scenes eventually lead to Marvel exercising the six-month clause and giving Liefeld the boot. Avengers and Cap would be fall under the WildStorm umbrella for the duration of the Heroes Reborn contract, and that was that.

Liefeld was quickly becoming a pariah in the industry. His unreliability had caused a chilling effect in many of his staunchest supporters; his unpredictably-shipping comics weren’t exactly raking in the profits (Prophets, heh); his brash, “I can do anything I want” attitude was alienating pretty much everyone, which would ultimately lead to his departure/dismissal from Image in the coming months. But before he left, his Extreme editor, Eric Stephenson, had a luncheon with one of comics’ most storied, cherished scribes wherein they talked at length very lovingly about how the sense of wonder they’d beheld in the comics of their youth wasn’t really there anymore – at any company. Moore approached Stephenson with an idea for a way to look back at the past in a way that wasn’t just some blatant nostalgia romp. Stephenson immediately signed off on the deal, and took it to Liefeld, who did the same. And in doing so, he proved everyone wrong about him, who he was, and what he was really about. He gave his third-tier Superman knockoff comic, Supreme to Alan Moore to scribe, quietly launching in August 1996 – a month prior to Heroes Reborn sucked all the oxygen out of the room.

Moore had, of course, worked with Image before. He’d also done some one-offs here and there, and was in the middle of a much-heralded (but hardly world-changing) fifteen-issue run on WildCATs at the time, too. But other than that, he’d spent most of the decade hiding from the spotlight that Watchmen had put on him, choosing instead to focus on low-profile work like From Hell with Eddie Campbell in England’s legendary Warrior Magazine and what could charitably be called “paycheck gigs” like Violator vs. Badrock at Image. And although his Supreme run wouldn’t exactly set the sales figures on fire, it was his signal to the world that he was ready to get back to deliberate, thought-provoking superhero writing – albeit in a manner that was the opposite of his deconstructive streak in the ’80s. Instead of breaking the superhero down to his barest psychological components, Moore instead wanted to celebrate what was great about the superhero in the first place.

For the duration of its existence to that point, Supreme had existed as a sort of Liefelded-up version of Superman, firmly affixed in his Extreme universe and stylistically Youngblood-adjacent. And as we’ve discussed in previous chapters, exactly what Image had specialized in for the first four to five years of its existence. Violent, over the top, thinly-plotted, and lacking much in the way of characterization, Supreme was the perfect vehicle for Moore to restart from scratch. So perfect, in fact, that he made the character’s relative lack of depth and fleshed-out past part of the book’s new meta-narrative right out of the gate: just on page two, Supreme uses “micro-sight” without thinking twice, before realizing he has no idea how long he’s even had this power. I can’t remember, he narrated in old-school thought balloons. So much of my history is a complete and perfect blank. Moore was deliberately casting the character’s lack of concrete backstory into a part of the story itself, which quickly revealed itself to be a meditation on the nature of superhero comics and a love letter to Silver Age Superman wonderment. Moore took Supreme from afterthought to Eisner-worthy in a single issue, number forty-one.

In the story, Supreme returns to Earth from a mission in outer space, only to find the world shifting and changing around him. As it and its inhabitants flicker and shift and change around him, a confounded Supreme was approached by three variations of himself:

The variants, reminiscent of a certain Man of Steel’s many, many Silver Age variations (from, naturally, imaginary tales or dreams!) ushered the “Platinum Paragon” to a realm called The Supremacy, where all imaginable past iterations of Supreme resided after reality was “revised.” This Valhalla of sorts was populated with every Supreme from every era: Squeak the Supremouse, Macro Supreme, Original Supreme, Sister Supreme, Grim ‘80s Supreme, and more. Any time reality was “revised,” i.e. rebooted, retconned, or tweaked in the real world – another wicked little tip-of-the-hat metacommentary from Moore, the old Supreme would be deposited to this fantastical world. “New” Supreme, as it turned out, had gaps in his memory that could actually be attributed to his lack of backstory by previous series writers. And, to boot, he was only “a few months old.”

This meta approach to writing superhero comics was as much of a one-eighty from what was traditionally expected from mainstream comics in general and Image in particular, that this loving homage to Silver Age DC comics felt fresh and new despite the fact that as the issues continued to roll out, more and more segments of the story would be devoted to backstory written and drawn in the particular styles of whatever period the flashback was evoking: 1950s EC, pre-Comics Code crime comics, late Golden Age funny animal yarns, and of course, Nuclear Age-inflected DC. More than just a gimmick, these flashback sequences would slowly unwind Supreme’s past and new origins, allies, foes, and love interests. They were all drawn with loving care and period detail by Rick Veitch, who showed off a learned, almost reflexive ability to mirror the styles of each period being evoked:

The remaining interior pages would, for awhile at least, be drawn by Joe Bennett. Bennett brought an Image-like sensibility, juxtaposed against Veitch’s more refined, deliberate stylings. He would eventually step aside and the more minimalist, classicist stylings of Chris Sprouse would take the wheel, refining the general look of Supreme’s world to one that was more directly descended from legendary Silver Age Superman artist Curt Swan, who coincidentally, passed away the same year of Moore’s revamp. (Bennett would continue working in the industry for years to come, and seemed to finally have arrived with his work on Marvel’s Immortal Hulk when his entire career unraveled when he was revealed as virulently anti-Semitic.)

But insofar as Liefeld’s luck in being able to turn Moore’s vision into extended goodwill at Image, the clock had run out. After just two issues, the mounting tensions between him and the other founders and shareholders resulted in him moving Supreme and the rest of his titles to his independent-from-Image Maximum Press (claiming it to be a superior company), and within a few months after that, he and Image had their epic, public, nasty divorce.

Moore, though, soldiered on without missing a beat. His initial story arc stretched a full thirteen issues and three publishers (Image, Maximum, and Liefeld’s new post-Image endeavor, Awesome Comics) and effortlessly created analogues for just about any touchstone imaginable from Silver Age DC lore: Batman and Robin, Lex Luthor, Martian Manhunter, Lois Lane, Jimmy Olsen, Perry White, Smallville, Supergirl, the Legion of Super-Heroes, Krypto the Super-Dog, the Justice Society, and even Wonder Woman (a re-imagined Glory, another Extreme stalwart). And through it all, Moore wove a deft, heartfelt love letter to the wonder of the comics he’d grown up with, and did so in a loving manner nobody could have predicted. Supreme would go on to win the 1997 Eisner Award for Best Writer with Moore. His run would continue for a little while more after the initial story wrapped, but instead focused primarily on single-issue stories. He’d told the main story he wanted to tell, but would hang on a bit more with some less-sweeping stories to tell, before moving on to other things (namely, shaping his own line of comics through an imprint at WildStorm, America’s Best Comics). Eventually, Moore’s unpublished scripts saw the light of day as Supreme: The Return in 1999. (Of note, plans had begun in 1997-98 for Moore to completely re-imagine the entire imported former Extreme universe, casting it in the mold as Supreme, but beyond two issues of a brand-new Youngblood that functioned as a rough analogue for the Teen Titans, a three-issue miniseries Judgement Day that wrote a new meta-history for the entire universe, and a couple of odds and ends, nothing came of it.)

Although the bulk of this chapter takes place external to Image, it’s important in that it showed just how adaptive the company could be – when it wanted to. After all, who wouldn’t give Alan Moore a chance to do whatever he wanted with their comics line? And Supreme was absolutely an early Image book, hearkening back to those halcyon days of 1993. But the fact that a comic few readers really cared about could be so convincingly re-imagined a something else, something new, and touch on an entire era of comics history that nobody could have predicted would connect so well to the (perceived, rightly or wrongly) Image house style. Supreme was something special, and it proved that even among its early slate of books, Image was no one-trick pony.

And as for Rob Liefeld, despite his propensity toward self-aggrandizement, he isn’t the villain many make him out to be. He’s a guy who became a millionaire at age twenty-four and became the face of the hottest new comics company of the decade (whether he meant to or not, for better or worse), whose career shot to dizzying highs in a relatively short amount of time. Few people wouldn’t let that kind of success go to their head – or let it get them in over their head, as would be the case with his and his company’s shoot-from-the-hip management style. In fact, in the years after he and Image parted ways, rather than change for the sake of appeasement, Liefeld more or less doubled down on the stylistic tics that had made him such a hot commodity to begin with. He’s been a vocal proponent for creator rights, and helped many new up-and-comers launch their careers. He’s done work for Marvel, DC, and eventually would rejoin the table at Image – and everywhere he goes, every new comic he produced or variant cover he draws, he creates a piece of art that’s immediately identifiable as his. Few artists in comics history can claim that, and fewer can claim as stark fealty to their creative guns as Liefeld. Love him or hate him, there’s no denying the man that. And for that reason, he’ll always have a fandom, and can be assured he has his own place in comics history.

NEXT: Strangers in Paradise brings soapy drama to Image with a much-needed dose of queer representation – at a point in time when such things were few and far between, and often beholden to bad stereotypes.

For Chapter 1: Youngblood, click here.

For Chapter 3: Savage Dragon: click here.

For Chapter 5: ShadowHawk, click here.

For Chapter 8: 1963, click here.

For Chapter 9: The Maxx, click here.

For Chapter 11: StormWatch, click here.

For Chapter 12: Spawn/Batman, click here.

For Chapter 13: Gen 13, click here.

For Chapter 14: Astro City, click here.

Chapter 15: Bone COMING SOON

For Chapter 16: Witchblade, click here.