Welcome to Image30, Comic Watch’s celebration of three decades of Image Comics! Throughout 2022, each week we’ll take a look back, chronologically, at the comics that built the publisher into the powerhouse it is today, and changed comics forever! In doing so, it’s our hope to paint a clear and definitive picture from a finished product perspective how the company originated, grew, evolved, and changed into the diverse juggernaut it is today.

Image30 Chapter 19:

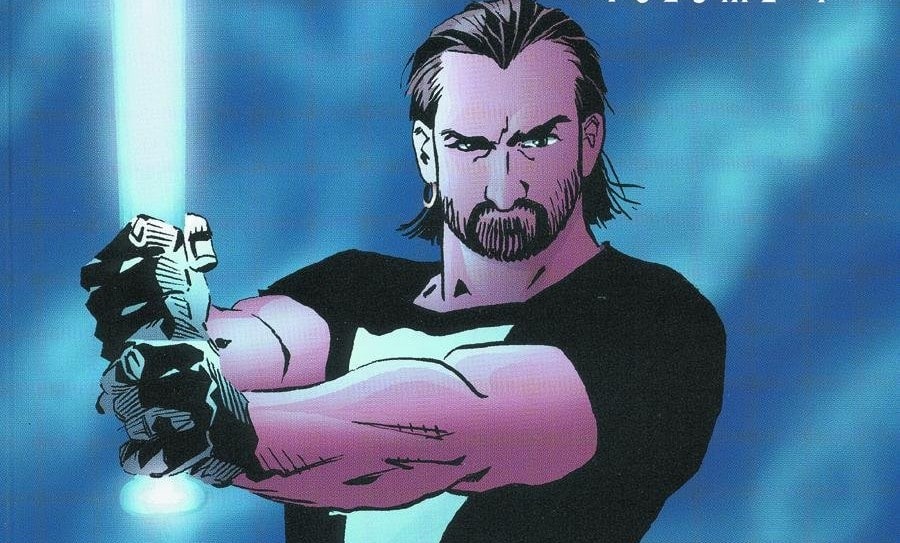

Mage: The Hero Defined

Although it has been the most commercially successful and second-longest-lasting (after Dark Horse), it should go without saying that Image was very, very far from the first independent comics company. To the contrary, it was the inheritor of a rich history of indie rivals and competitors (even if only a little) to Marvel and DC, the ever-enduring twin monoliths of the comic industry. To that end, there would inevitably be that one company that finally broke through and not only took a significant bite out of the Big Two’s sustained market dominance, but actually held onto that bite and didn’t let go. And to that end, Image has routinely enjoyed a comfortable 9-11% market share each month for a good, long while now.

But to get to that point, someone had to pave the way. And to get to the beginning of that road, we have to go all the way back to the 1950 – not exactly an era most would associate with freewheeling comics anarchy, or non-conformity, or anything remotely resembling progressivism in any sort of mainstream sense. But I digress.

Post-Comics Code, any publisher that didn’t get an almost immediate axe (read: E.C.) pumped out superheroes, romance, G-rated Atomic Age sci-fi, or the innocuous cutesy of Archie or Harvey publications. It was all aimed at kids, almost exclusively boys under age ten, and that was pretty much the state of the comics industry until Marvel came along and started punching up, (rightfully) reasoning that older readers – well into their college years, even – still thought four-color worlds were hip and cool, and the entire game changed. A whole new demographic opened up, and the sky was the limit. But by the late ‘60s, those same college kids were finding their own grooves, tuning in, dropping out, “smoking the marijuana cigarettes,” and ostensibly taking the counterculture mainstream (or at least, challenging the mainstream in a public enough way that the counterculture would eventually be absorbed by the mainstream). And with that newfound ethos came the germination of what we think of today as the independent comics scene.

The burgeoning “comix” movement (inasmuch as it can actually be called a movement) was as loose and groovy as the Haight-Asbury scene, but if nothing else, it gave the world R. Crumb, Trina Robbins, and a host of other important creators that spun from its womb. Comics about sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll, baby… printed with love in black and white and distributed outside of conventional means (not dissimilarly to the 1980s’ tape-trading scene). And since the comix books didn’t have to worry about encumbrances such as the Comics Code, they could do any damn thing they wanted. And it did, but at the end of the day, Zap and its peers were as much about shock as they were anything else. But like many things of that era, it was a great, albeit loosely-constructed idea that was full of heart but ultimately wasn’t built to last. However, it absolutely set the stage for what was next to come.

The ’70s saw a few sporadic indie publishers here and there pop up, but outside of Aardvark-Vanaheim (home of Dave Sims’ Cerebus), Gary Groth’s Fantagraphics, the one and only Rip-Off Press, and Wendy and Richard Pini’s WaRP Graphics (home of their Elfquest opus), none of them went anywhere. That didn’t stop well-intended creatives and would-be mini-moguls from trying, though. (A case could probably be made for Martin and Chip Goodman’s year-long disaster of Titanic proportions known as Atlas Comics, but the less that’s said about that, the better).

But a very, very significant thing happened in the early ‘80s that made a new emphasis on independent comic creation not only a thing of renewed importance (and interest), but one that could actually prove sustainably viable as a business if done properly: the direct market blew a hole in the side of the decades-old newsstand distribution model, and then some. And while the direct market had been bubbling under the surface since the late ‘70s, 1982-83 were the years that really saw it take hold and change the landscape of the entire comics market. Suddenly, any publisher could bypass the old-world way of distributing their work and get it directly into the hands of the sellers, bypassing the middleman completely and reducing the cost of doing business exponentially. That meant that a small company like Eclipse, Pacific, Mirage, Caliber, First, or Comico didn’t have to fight Marvel or DC for highly-coveted rack space; they could sit equally on shelves in the fledgling brick-and-mortar comic book store market. (Which in and of itself was the other piece of the new-model indie puzzle.) And since they were publishing with complete autonomy and outside the traditional distribution channels, they could all run without the Comics Code watering down their work. A brave new frontier opened up for a new generation of comic creators. These men and women were entering the field from a starting point of creative control – not only being afforded the chance to birth their works into the world, but actually owning them, too.

And so (in a very small nutshell, anyway) was born the ‘80s indie comic boom, a movement that would ultimately crescendo with the rise of Image in 1992.

Eclipse Comics, founded in 1982 as the boom was just beginning to explode, was based out of Pennsylvania and founded by local art school students Gerry Giovinco and Bill Cucinotta. Their first comic, Primer, printed in glorious black and white, introduced a handful of characters that would go on to try out their own books before disappearing forever, but the second issue introduced the world to writer/artist Matt Wagner and the first of his two signature creations, Grendel. Essentially a reverse Batman – rich, super-skilled and hyper-intelligent guy decides to be the world’s greatest criminal instead of punching criminals in the head – Grendel was a hit for the publisher, so much so that by the time Comico was flush with enough cash to introduce color comics in 1984, Giovinco and Cucinotta gave Wagner a shot at being the company’s poster child with a second creation, Mage: The Hero Discovered.

Mage was part modern Arthurian fable, and part autobiography. The comic’s main character, Kevin Matchstick, discovered himself to be the avatar of the original King Arthur, and all that entailed. Matchstick looked like Wagner; specifically, the Wagner of that particular period in his life. He would go on to meet other Arthurian archetypes, wield a bat that channeled the fabled Excalibur, and battle the forces of evil as they arose to challenge him. It was a personal work for Wagner, particularly since his own personality was all over the protagonist. Readers felt like they had a connection not only with the work but with its progenitor in a way that few other comics at the time did, and they rewarded Wagner with budding superstardom all his own. It wasn’t long before DC came calling, offering the up-and-comer a chance to re-imagine Jack Kirby’s Etrigan in a miniseries, followed appropriately with other with other various and sundry projects.

The original Hero Discovered, the first act in a planned trilogy, wrapped with issue fifteen in December of 1986. A second volume was announced – The Hero Defined – but it wound up not being until July 1997 that it would see the light of day at a completely different publisher: Image.

Comico, like so many other well-intended independent publishers of its time, had made the occasional bad business decision. But in 1986, it made a disastrous one that would ultimately lead to the company’s shuttering four years later: they made a play for the newsstand market, which caused their distribution costs to balloon exponentially to unimagined amounts they didn’t have the capital to cover, ending in bankruptcy and closure. Such a fate (similar or otherwise) was in store for many an independent publisher from the era, but insofar as Matt Wagner and Mage was concerned, there was an added wrinkle. Wagner couldn’t just walk away with Kevin Matchstick and company and take them elsewhere – Comico was part owner of the property, as part of their initial deal with Wagner. And since the company was bankrupt, those properties they co-owned (Wagner wasn’t alone in this boat) were suddenly a whole, whole lot more valuable to Comico’s disgraced functionaries. Various legalities had to be overcome, which took several years to straighten out, before Mage and Wagner could finally be properly reunited.

But as it turned out, the eleven-year gap between volumes played to the series’ strengths. Since Mage and its characters were rooted in Wagner’s real life and his own personal supporting cast, that he had more than a decade’s life experience between acts one and two of his saga meant that he was able to take Kevin Matchstick’s story in whole new directions with a newfound maturity that he couldn’t have possibly pulled off (at least not as convincingly) in the intervening years. That maturity proved prescient, in terms of storytelling: the older, wiser Kevin Matchstick found himself surrounded by avatars of other myths: Kirby Hero channeled a particularly Herculean, well-intended but oft-times boneheaded approach to heroism; Joe Phat, the embodiment of the coyote from various Native American mythologies, was quiet and wise. Allowing the other mythologies space to flourish and be a part of Matchstick’s world allowed Wagner to grow as a creator, forcing him to learn about new things to credibly add them with authenticity.

It worked, too: The Hero Defined was a huge hit for Image, and ran a complementary fifteen issues to its predecessor (as would the eventual third and final volume, The Hero Denied). Here was a respected creator from another time in comics history, returning to the independent comics scene he’d helped foster with one of his signature creations, continuing the story on his terms under his vision. And as a bonus, Mage found not only a whole new audience, but far, far greater exposure as part of the Image family than it ever could have under the much-smaller Comico.

One of the things that often gets left out of the conversation when talking about Image and its place in comics history is that it’s standing on the shoulders of many, many independent companies that came before it. That it took the unprecedented (and very public) exodus of Marvel’s top artists to help it get a top-tier start is, in this situation at least, beside the point. There’s a rich heritage of independent creators and publishers that laid the foundation for Image’s success, and there’s no denying that Image almost certainly wouldn’t have happened without their precedent. Or maybe it would have, but it would have looked much different. Sure, Comico, Eclipse, et al. didn’t have the sheer star wattage that Image’s founders had, but they had something else: a belief that as creators, they had something to say that readers wanted to hear that wasn’t being said by the Big Two. That ethos, that dedication to craft, is absolutely the bedrock of Image, immediately alongside creators’ rights.

And in choosing to bring Matt Wagner aboard to continue Mage, Image was, in its way, honoring that past. The black-and-white 1982 past was connected to the computer-colorized 1997 present. Hero Defined would conclude in October 1999, and it would then be eighteen years before the third and final volume, The Hero Denied. But in that time, Matt Wagner became an A-list creator, crafting stories for Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman (DC’s Trinity maxiseries), occasionally returning to Grendel at Dark Horse, painting a series of still-iconic covers honoring Oliver Queen’s return from the dead in Kevin Smith’s cherished Green Arrow run, and essentially becoming a creator’s creator. The guy who had a vision fresh out of art school, and a firm belief in himself that he had stories to tell that people would want to read. And he was right.

And if that’s not what Image is all about at the end of the day, I don’t know what is.

NEXT: The Darkness continues the Top Cow renaissance kicked off by Witchblade!

For Chapter 1: Youngblood, click here.

For Chapter 3: Savage Dragon: click here.

For Chapter 5: ShadowHawk, click here.

For Chapter 8: 1963, click here.

For Chapter 11: StormWatch, click here.

For Chapter 12: Spawn/Batman, click here.

For Chapter 14: Astro City, click here.

Chapter 15: Bone COMING SOON