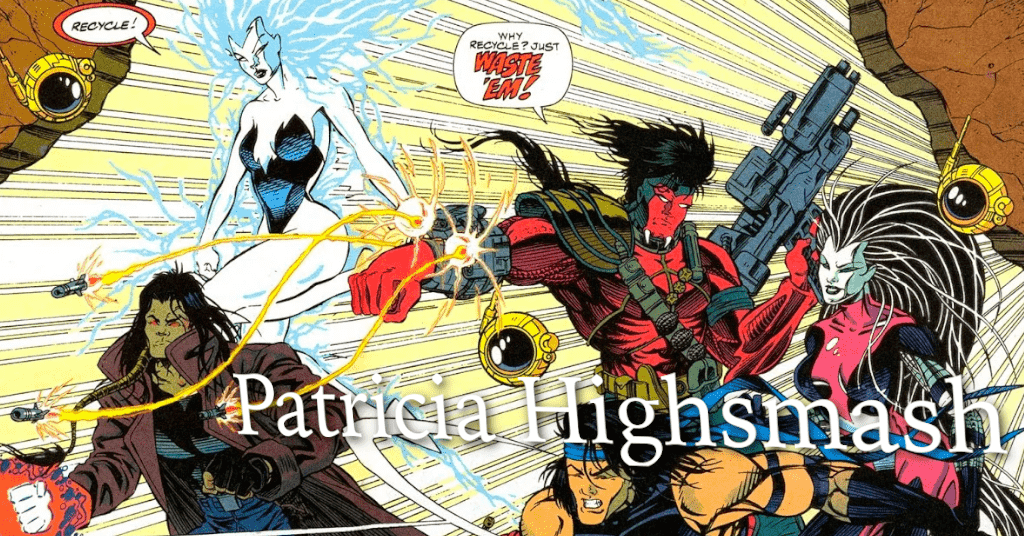

Patricia Highsmash

Peekaboo Objectification: Blood Pack

by Travis Hedge Coke

“We are not a team!”

“We sure as hell aren’t heroes.”

“We’re just weirdos paid to be together.”

Sometimes a comic ages into its relevance. Sometimes, it is the localized culture which has to catch up to admitting or addressing the parts which always were relevant. Blood Pack (Charles Moore, Christopher Taylor, Andy Lanning, Scott Bauman & Chris Eliopoulos) is a 1995 DC Comics miniseries concerning a reality show based around a manufactured superhero team. It is somewhere between.

The first thing to grab us, any more, is that the comic is edited – or, alternately, “executive produced” or “directed,” as credits refer to it – by Eddie Berganza. Anything the comic has to say or demonstrate in regards to objectification, sexuality, abuse, corruption or victim-sympathy becomes suspect now that Berganza’s history of alleged abuse and corruption. This is no fault of anyone working on the comic in earnest, and cannot erase any audience’s response to the scenes, characterizations, or work. It has an undeniable impact.

Blood Pack was unlikely to ever be a success at the time of publication. Tied to a very loose crossover event, in which all of DC Comics’ annuals presented a new character who gained super powers when a group of mob-like aliens riffing on those xenomorphs from the Alien franchise came to Earth to prey, even the more intriguing or unique of the characters often felt forced, and the majority of them were awkward, fluff stories which introduced characters who seemed destined to be background fodder if they ever appeared again.

The success from the Bloodlines event was Hitman, an inherently satirical character in a satirical story; a hired killer whose Hitman monicker was only ever mocking superhero-universe conventions.

Other series launched for certain characters, but they were all short-lived and like Blood Pack, the deck was stacked against them and the table had been soured before the bets were in or the cards laid face up.

Blood Pack has an advantage in this condition, in that in could be direct in its commentary and characterization. It could be unfancy in an affective way.

Blood Pack feels more like a 1980s AC Comics or Heroic release, closer to early Ultra Comics or Malibu, than the refined and careful DC Comics of the mid 1990s. There is a bluntness, and an economy of characterization, which feels like the artists and writers could not even be sure they would have four entire issues released. Part of the logo from a gay periodical, Bear Magazine, in a women’s dormitory, blink and miss it touch, but pushing boundaries, nonetheless. A desperate energetic telling and showing ensues and does not let up for the entire miniseries.

Mongrel is mixed-race, filled with shame, afraid of touch. Ballistic is chill, experienced, and strapped with weapons at all time despite having an armored body and super strength. Nightblade is a fame-chaser who cut off his own hand to look impressive on camera (it grew back). Cameras follow Sparx and Razor Sharp in the bedroom they have to share for the entertainment program that is Blood Pack, tracking them in their underwear for a waiting audience.

Ten years after Blood Pack, Marvel Comics would see X-Force transfigured into what would become X-Statix, under the control of Mike Allred and Peter Milligan, a similarly-themed and similarly critical comic, but at the time of Blood Pack, reality television was only beginning, the purview of MTV shows like The Real World and the occasional dating program or manicured copaganda, Cops.

That a producer would condone and cover up for the murder of a star who wants to quit was not shocking then, nor would be now, but the Blood Pack feeling a total lack of recourse and the way in which they are talked around to simply rolling with it – why rock the boat – is both seductively naive and predatorily executed.

The Jamiroquai and big hair anime posters on the dormitory wall almost highlight how much reality tv and its criticism were in infancy. The Nagel prints and yuppie parodies remind us how tethered to the 1980s the mid-1990s still were, particularly in comic books. The Greatest Flash Stories Ever Told makes an appearance in one issue, as does a stuffed Batman doll, indicating the nature of the Flash’s and Batman’s celebrity in the DC Universe, in comparison to Blood Pack’s. Some of these characters are signing up to play superhero because they are superhero fans, or at least, aware superheroes can be powerful and famous.

A world in which Batman can be a toy and Bruce Wayne’s family name is on Monopoly boards is both our world and not ours.

In the superhuman world, only Impulse – a child in his early double-digit years – is a fan. Established superheroes like Superman or Jade come off smug, glib, and disconnected from the social reality of the Blood Pack cast, who equally seem vapid, anxious, and naive in their own branded-as-youthful way. The young Superboy is a different, older generation, than Blood Pack, because he is marketed as so by Blood Pack, while Ballistic, who is definitely closer in age to Batman than Jade or the kids of his own team, is youth-branded.

Sparx putting Bear Magazine on her wall, covering her bed in Batman and Robin stuffies and a leather daddy teddybear is a visual characterization that sets her apart from previous generations of superhero, and her portrayals in many other comics, before and since.

Blood Pack know they are being used and marketed. They can be murdered for not participating. They can be degraded, objectified, manipulated by their producers and crew. Sexualization is amped up and intelligence and compassion are often derided or erased with smarmy catchphrases and slogans.

The “most [people] on Earth” weaponizing shame, marketing, responsibility, doxxing and false records to enslave multitudes and direct the global politic.

The show, the concept, explode upon themselves mid-production. The comic seems to believe this level of manipulative engagement is partly unsustainable and simply the methods by which entertainment is produced.