Welcome to Throwback Thursday, where Comic Watch celebrates great comics from the past you might have forgotten about!

Power Man and Iron Fist #123

Power Man and Iron Fist was easily the most underrated and under-appreciated comic Marvel published in the late 1970s and much of the ’80s. Born out of the idea that both title characters inextricably tied to fads from the past (Blaxploitation film for Cage and the kung fu craze for Iron Fist), but were both essentially solid characters outside of those limiting genres. So when Cage’s solo title (then diluted from its roots to simply being called Power Man) was on the brink of cancellation, some unsung hero had the ingenious idea to retrofit it by pairing Cage with his temperamental and stylistic opposite, Danny Rand, and turn it into an odd couple book. It worked wonders far better than anyone could have hoped, and a cult classic was born.

However, PM/IF (as it was colloquially known) was never particularly invested in tackling ideas of race when it came to one half of the book’s starring equation. Sure, Cage’s race would get brought up from time to time, but primary series scribe Jo Duffy was more focused on relatively light-hearted adventuring than she was tackling complicated questions of race in America. That’s not to belittle her amazing stint on the title, because it set the tone for the book after a brief status quo-setting introductory set-up by Chris Claremont. But for all of its strengths, Duffy’s run simply wasn’t built to dive into thorny questions of race relations, historical inequalities, Black people’s complicated relationship with the police in America, or any of that. (And as a white person, in hindsight it’s probably for the best that Duffy didn’t make the attempt.)

However, by the mid-’80s, PM/IF‘s sales were flagging, and the book was headed toward cancellation. Enter writer Christopher Priest (then going by his birth name, James Owsley), who had recently written a decently-well-received Falcon miniseries but was transitioning out of his role as editor and still finding his footing as a writer. Priest wrote the final fifteen issues of the series, and brought a more somber tone to the book, taking Luke Cage and beginning an evolution for the character from Blaxploitation trope and Black superhero to fully-realized, three-dimensional character that’s far more familiar to modern readers. Priest’s Cage was irritable, and maybe even a little angry without falling into the “angry Black man” cliché – but Priest was smart enough to show why he would have that temperament. He was constantly having to deal with daily microaggressions from people who saw him as a Black person first and automatically made any number of assumptions from there.

And then there was Tyrone King. The character, introduced by Priest as a romantic interest for Misty Knight, was a Black cop who despised Cage for being a hero for hire, and whom Cage despised for refusing to be anything other than colorblind to himself or any other Black person. In Cage’s mind, King was an Uncle Tom, and in King’s, Cage was only a “good guy” when the price was right. It was not a happy relationship.

This was the level of complexity Priest immediately injected into Power Man and Iron Fist. No other comic in the mid-’80s was looking at matters of race with this kind of magnifying glass or sense of nuance, and certainly not from the perspective of a Black comics writer, of whom there were (and sadly still are) sparingly few. All of which brings us to Power Man and Iron Fist #123, the next-to next-to last issue of the series. The story, entitled “Getting Ugly,” pulls absolutely no punches but also offers no easy answers, leaving the reader to make their own conclusions about what they’ve just read, instead of Priest lecturing from on high – which was surely tempting, given the story’s topics.

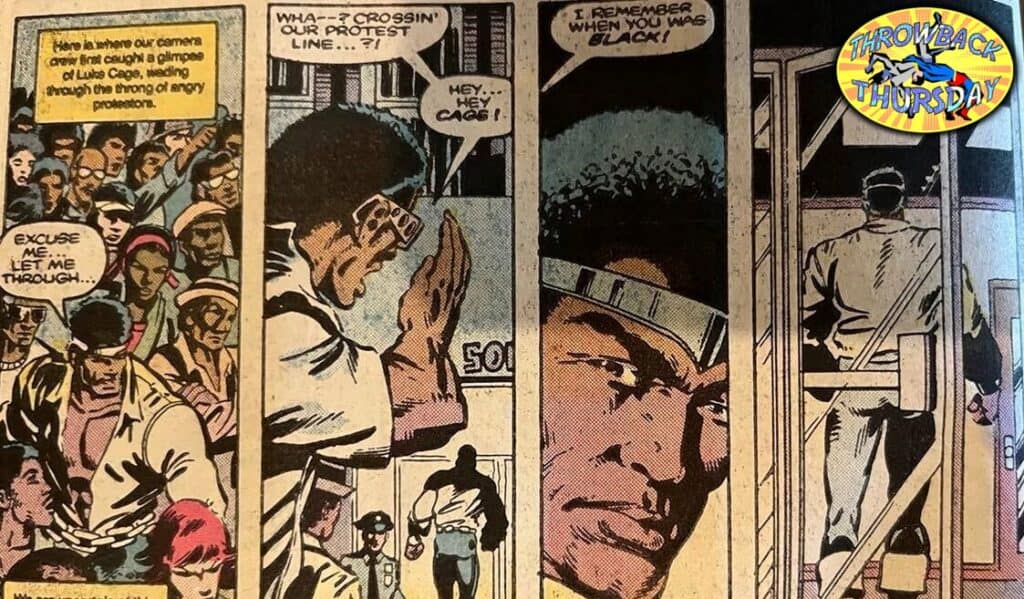

The story opens in the aftermath of an incident in which a glowing, hulking superhuman named William Blake smashed his way out of the boarding room he’d been staying in, yelling racial slurs at the woman and her two children with whom he’d been staying. Police were called out once he smashed through a wall, and of all the officers on-scene, he three he chose to kill were all Black. It doesn’t take long before pre-internet word of mouth spreads, and pretty soon, a conspiracy theory has taken hold of the Black community that the police are dragging their feet in the investigation because the victims were Black. As a result, near-riot breaks out at the local police precinct. Cage has arrived to help since the suspect is super-powered, but the moment he crosses the protest line to enter the precinct, he’s called a sellout and told he’s forgotten he’s Black. The comment strikes Cage at his core.

Once inside, Cage and Tyrone King work uncomfortably with the precinct’s computer tech to get some information on the murderer, Blake. There’s a sitcommy bit here where either Priest doesn’t quite grasp that then-new personal computer technology can’t be “fixed” by banging on the monitor like it’s a stubborn engine or something; or if he did grasp it, the intended joke doesn’t land. But what seems like a throwaway gag winds up being crucial to the conclusion of the story. So with the magic of the computer, they discover some pretty relevant information…

And with that, the chase is on. King, distrustful of Cage, heads off without him, nonchalantly telling him that he can’t afford his price, which incenses an already-stinging Cage. Blake charges into Harlem and immediately begins attacking the first Black people he sees – which isn’t that hard. Falcon, then in his role as a social worker, joins the fray, and helps protect as many innocents as he can while King gets the drop on the assailant and manages to fell him with gunfire, which slows him to unconsciousness but in his superhuman state, does little more. Cage, much to his chagrin, missed the fight entirely, which further bruises an already-hurting ego, and the subsequent buzz on the street does little to make things better:

Then things get worse – the Marine Corps, looking to cover themselves due to their giving Blake his powers, intercepts him from police custody and takes him into theirs, which further stirs the pot as now it looks like Blake won’t be facing any type of justice at all – which puts Tyrone King uncomfortably on the side of the protesters, as he defies orders and arrives at the military installation amid the angry crowd to conduct a second formal arrest so that justice may be done. But before he can, Cage and Falcon charge the scene, eschewing the niceties and breaking into the facility. King joins them in their efforts, but it’s ultimately Cage, wrestling with so many emotions, who winds up squaring off one-on-one with Blake.

Priest asks some seemingly straightforward questions with more nuance than might be expected – especially considering this was thirty-six years ago. Should Cage feel guilty for working with the police, the source of so many injustices over the decades toward Black people? Should his first priority have been to the Black community? Should the fact that Blake’s mental state has clearly been effected by the botched procedure the military did to him make him any less culpable for the fact that his bigoted beliefs lead to the deaths of three Black men? Is King right or wrong to be self-colorblind? Does the fact that the murdered Black men were police officers make any difference to the equation? As expected, Priest offers absolutely no easy answers – and in fact, when the final twist is revealed after Cage inevitably wins his duel with Blake, those already-complicated questions get completely turned on their heads one last time:

And just like that, everything we think we know about this story flips on its head. The entire equation has changed: Blake’s race was erroneously put into the computer as “Caucasian” instead of “Black.” The media’s perspective shifts from “vicious race killer” to “misunderstood soldier” or “victim of society -” missing the point entirely by boiling a complex issue down to an easily-palatable bullet point instead. The fact that Blake turned out to be Black instead of white doesn’t absolve him of his crimes, but it muddies things entirely by turning him from an obvious metaphor for white supremacy to a maybe a self-hating Black man instead. Or he might not have been; the procedure done to him by the military perhaps just scrambled his brain. If that were to prove true, does that aspect make him any more or less guilty?

Priest closes the issue with all of these questions left open-ended and unanswered, never spoon-feeding anything to the reader. It’s an incredibly somber, powerful reading experience, and sadly much of its narrative is just as relevant today as it was in 1986. And it’s worth noting that the issue was the product of not one but two Black men in America; Priest, of course, and artist M.D. Brown, with whom the former had teamed for the aforementioned Falcon miniseries. This is a story that’s clearly near and dear to both creators’ hearts, and they don’t pull any punches, no do they make it easy on the reader. That this story was told from the complex perspectives of not one but two Black men, and not watered down or held back at any point by anyone else, shows that Marvel had a lot of trust in both of them to convey an incredibly complex and important story without interference. That matters, not just from a representation standpoint but from a truth-to-power perspective, too.

Power Man and Iron Fist lasted two more issues, ending with one of the more controversial conclusions in modern comics history. Luke Cage and Iron Fist’s time had passed, and both characters went on the shelf for the next few years. Christopher Priest’s run brought both characters’ story (and partnership) to a reasonably logical conclusion insofar as coming full-circle goes (at least where Cage is concerned; Iron Fist wasn’t so fortunate). Endgame runs when writers know their comic is about to be cancelled usually go one of two ways: swinging for the fences because there’s nothing else to lose, or dying with a whimper because so few readers seem to care. Fortunately, Priest chose to take the high road, and with it, produced this quiet masterpiece of a meditation on race.