Welcome to Throwback Thursday, where Comic Watch celebrates great comics from the past you might have forgotten about!

Unknown Soldier (vol. 4)

TRIGGER WARNING: This article discusses rape, war, and violence done to children.

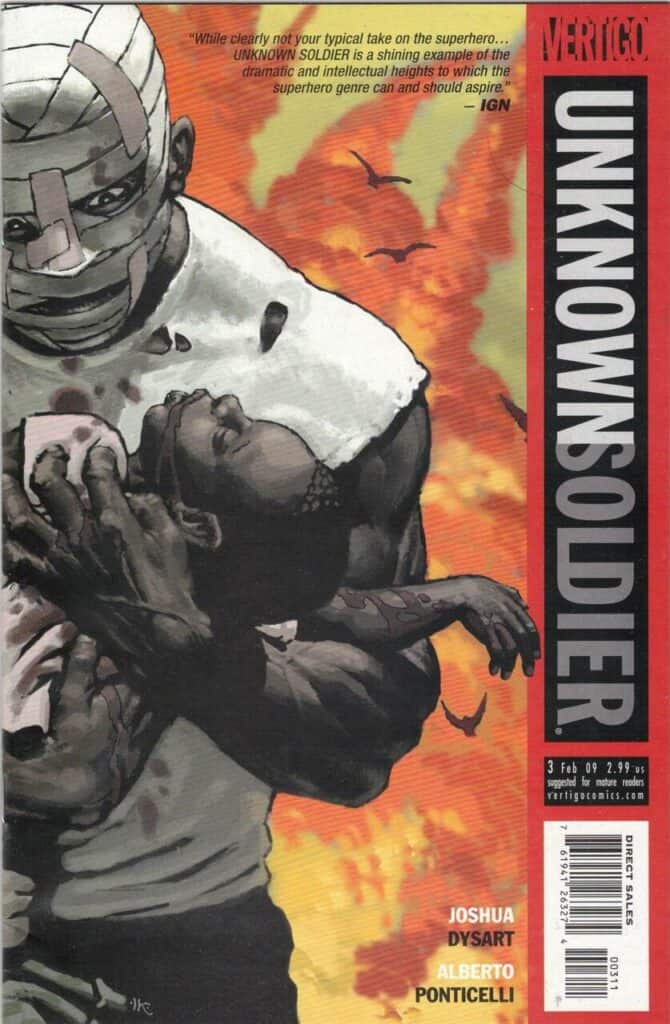

Full disclosure: I’ve been reading comics religiously and regularly for over thirty years, and I’ve read it all. Plenty of comics that contain material that might make “regular” people uneasy, I’ve read without blinking an eye: Preacher. From Hell. Walking Dead. Yet, no comic has ever left me feeling as deeply unsettled as Joshua Dysart and Alberto Ponticelli’s Unknown Soldier, which ran on DC’s Vertigo imprint from 2008-2010.

The series, set in Uganda in 2002, centers on Dr. Moses Lwanga, who emigrated to the United States from that country when he was a child. After obtaining his doctorate, he chose to return to the country of his birth, set on providing as much humanitarian aid to his war-torn homeland as possible. And while he did accomplish this to the greatest yet cruelly finite degree possible given impossible circumstances, he also was captured by child soldiers of the Lord’s Resistance Army, a rebel force led by megalomaniac Joseph Kony. Lwanga wound up killing a child to escape, and the act unhinged him, leading him to brutally scar his face with a rock, and hide his scarred visage in bandages. Lwanga pledged from there to hunt down Kony and execute him, hopefully bringing an end to the decades-old civil war that had claimed thousands.

That’s just in the first six issues.

Writer Dysart did his homework to the Nth degree for the series, the fourth at DC to bear that title. He traveled to Uganda itself, and in the first four issues of the series, wrote a supplemental, detailed essay chronicling the history that had led the country to a place where rape was weaponized and children were armed with AK-47s by a madman with delusions of a religious savior. There’s quite a lot to Uganda’s troubled and heartbreaking past, but essentially since 1986, it has been in a state of perpetual civil war, the abhorrent forces of Kony’s not-at-all-ironically-named Lord’s Resistance Army (itself a perversion of Christian ideology, with Kony situating himself as some sort of Second Coming figure) of the north against the weak, corrupt central government of the south. In typical post-Colonial manner, Uganda was pieced together as a country by European forces disinterested in historical tribal divisions, creating a nation tragically divided among itself since its founding in 1962. Once the playground of tinpot dictator, authentic monster, and purported cannibal Idi Amin, the forces that overthrew him were ill-prepared – perhaps by design – for the realities of administering a nation, and chaos has since ensued.

All of which brings us around to Unknown Soldier, the long-standing DC war comic, becoming a late-period Vertigo masterpiece that was tragically cut short just five issues before completion.

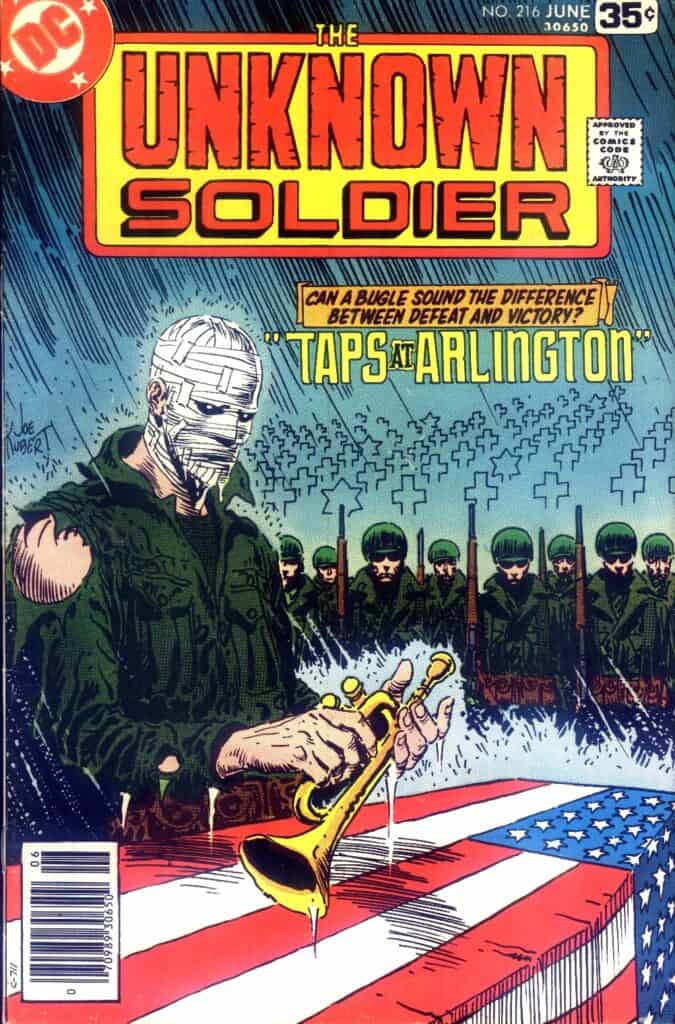

The original Unknown Soldier, appearing in DC’s venerable Silver Age war series Our Army at War beginning in 1966, took its inspiration from Arlington Cemetery’s Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, the famous famed memorial for soldiers killed in combat but unable to be identified.

The original Unknown Soldier, captured by GOAT war comic artist Joe Kubert.

Those Silver Age DC war comics were definitely Comics Code approved, but the writers and artists involved – many of whom knew the horrors of war intimately from their World War II service – but went as far as they could for the era to depict the horrors of war with a real sense of weight and respect (even the Haunted Tank took its subject matter seriously despite the uniquely wonky premise of, ahem, an actual haunted tank). Unknown Soldier stories stood out from the pack, though, perhaps by virtue of their title character’s anonymity. Because the Soldier was the living embodiment of war’s cold impartiality, his stories had a stronger sense of detachment and solitude than did the adventures of Sgt. Rock and Easy Company or Enemy Ace. Because the Soldier could be anyone, the wartime tragedies he endured could more easily imprint themselves onto readers.

Taking that concept and transplanting it to present-day warzone riven with atrocities that could easily stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the unfiltered evil the Nazis had wrought sixty years prior was a stroke of genius on Dysart’s part. As much a journalist as he was a writer, Dysart wisely understand that although he could have written a more straightforward story about the tragedies in Uganda, tying it to a known DC property like Unknown Soldier would give it a little more cache with fandom. Enticing readers to embrace such challenging subject matter, no matter how well-written it might be, is always difficult – more so when it’s cut wholly from brand-new cloth.

And make no mistake, the subject matter is challenging. The L.R.A. commits war crime after war crime both in real life and the series: child kidnapping and indoctrination as soldiers; child rape as “wives” for the grown men; mass murder; starvation tactics; genital mutilation. What makes all those things even harder to swallow is the sheer banality of them for even the non-conscripted Ugandan boys – they speak of things like murder and sex and brutality in a detached, lackadaisical manner the same way American might talk about football or video games. The girls speak of the possibility of becoming a “wife” to one of the soldiers with a warped, muted sense of pride. The thought that the L.R.A. might come round them up at gunpoint, tear them from their families, and force them to become warriors or wives in a war they barely understand is natural, even casual.

And that’s it right there, the thing that makes Unknown Soldier such a difficult yet urgent read: it isn’t about horrors of the past, to be reflected upon in history books. It’s about tragedies unfolding now, while the world grinds away and pays attention to more camera-ready stories from week to week as the twenty-four hour news cycle churns. Western culture doesn’t like to talk about difficult things that don’t impact them directly; it’s far easier to stick to stories for which viewers and readers have better context. To know the terrors in Uganda would require at least cursory knowledge of that nation’s history; most Americans would rather be distracted by The Masked Singer.

That Joshua Dysart chose to place his story in such a difficult setting makes the story that Unknown Soldier tells all the more urgent. Society needs to be reminded of the pockets of inhumanity it’s forgotten, lest that evil festers and grows and perpetuates. The current state of Uganda didn’t happen overnight, but it did happen while the world held its nose, looked the other way, and did nothing. Unknown Soldier is not an easy read but is one that everyone should at least try once to digest.

There are several organizations you can donate to whose work goes toward humanitarian efforts in Uganda, and elsewhere:

International Rescue Committee