There Is Nothing Left to Say On The Invisibles

3.06

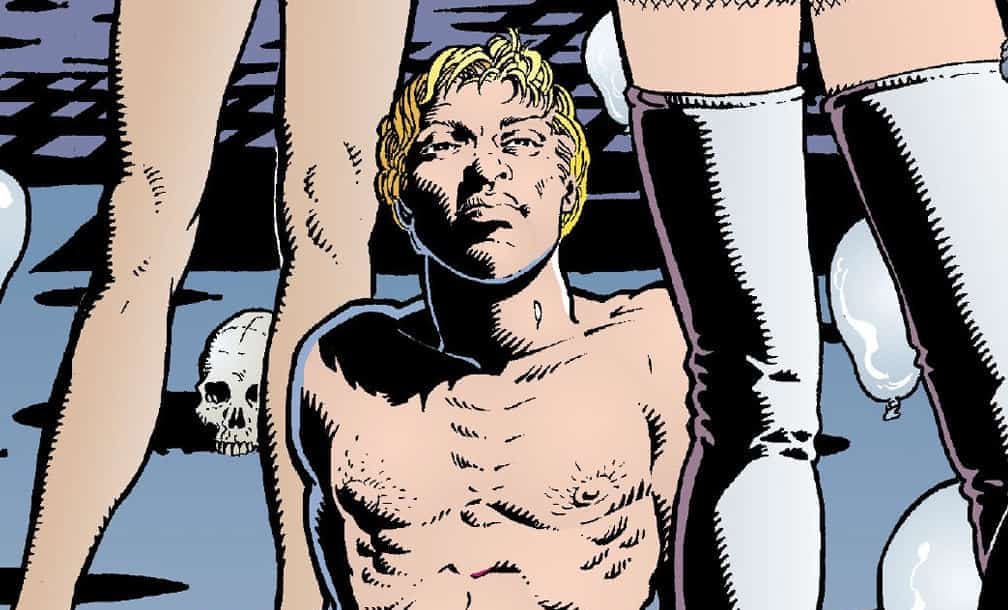

Dane’s Trip

by Travis Hedge Coke

In sixty-two serial parts, which break down into thirty-five titled arcs, The Invisibles, includes rituals you do for an hour, rituals you do for weeks, rituals you are long haul. The weekly serial comic habit is a ritual as much as prayer, fasting, flexing your pelvic wall, humming when you pee, or Ramadan.

You can try to read in order, all the number ones, the number twos, threes, fives, sevens, nines. And then you go back because the twelfth issue starts Volume Three, but it isn’t issue one. Light goes black and air pressure swoons you for a moment because you is rhetorical me and I have syncopy and realized this sitting up in a hot bath.

A significant shift occurs when we are aware how much information our senses take in, and how many senses we have. Talk of five senses or primary senses, but in reality we have many more and we know them. Sense of balance. Sense of temperature. Sense of time.

A tried and true meditational technique is downplaying our senses to retreat into no-smell, no-sound, no-taste, and in those states we still have tastes, sounds, smells. Embrace your senses. Let them overload. Let them overwhelm. Push yourself to identify or receive as many and much sensation as you can. Put your nose to work.

“Extraordinary and improbable as the contents of the volume may seem to those not previously convinced of the ultramundane nature of the phenomena described, the writer would ask the reader to lay aside all prejudices, or pre-conceived notions as to the other world and our future condition, so far as he is aware that they are merely the effects of education, or association, and are unsupported by any known facts; and to weigh the theories set forth, with an unbiassed mind, precisely as he would those relating to any other subject. ”

– The Invisibles: an Explanation of Phenomena Commonly Called Spiritual, MJ Williamson

In an October, 1993 missive to editor Stuart Moore, writes Grant Morrison, “Jack Frost is assigned the role of Spirit, which unifies and synthesises the other four [classical Euro-culture elements; water, fire, earth, air] through humor and creativity.” In this way, the other four members of the cell which Jack will join at the beginning of the comic, will all live through Jack. And, not only because he is the last storyteller standing at the end.

Jack experiences a particularly engineered awakening in the early parts of the comic, the Invisible in The Invisibles; our Invisible. His trials are calculated by the universe, by human agency and ghostly hand. His understandings of existence and politics and himself unfurl, they bloom with petals showing, then pollen, then petal, then pollen, often half-truths, truth by metaphor, and often metaphor by truth and the other half of truths.

Gelt uses persuasion techniques on Jack when he is Dane, when he is imprisoned at Harmony House. “Many people” this, pushing him to agree, to feel agreeable. Statements like, “The acorn grows into a tree like the tree,” feel like we should agree. That the onus is on us.

There are very TH White The Sword and the Stone narrative journeys of empathy for animals, empathy for people and place. The Sword and the Stone and its sequelae are sociopolitical works, written by a sadomasochistic repressed homosexual. A heavy drinker, he was described by a biographer as, Notably free from fearing God, he was basically afraid of the human race.” Like White’s protagonist, who will grow to be King Arthur of legend, in growing to be Jack Frost – the trick being they always are and were Arthur and Jack – Dane is presented with metaphoric ant-like people, the Myrmidon soldiers of his enemies, while White’s young king-to-be deals with literal ants as a metaphor, ants who think only in done and not-done.

What becomes unique with Jack, is that Jack can remember there is more than one kind of binary thinking, more than one binary language or world-processing. Jack is often unbothered of binarisms.

White’s empathetic animal tales might now swing or swish for human application.

The Ayn Rand fan might make a case against stories which, “make violence happen to characters,” as opposed to letting the violence occur, but what is make or let in the context of a wholly manufactured story?

Raised by a single mother he feels antagonized by, Dane casts out for replacement fathers. Dane’s history teacher tries to make him feel special and acknowledged, so he his kicks his teacher the head and bombs the library. He spends his nights with a group of boys or alone and arguing off his imaginary friend ghostly iced father. Being visited by some famous fellows of his hometown of Liverpool, two of the Beatles, dead but still there. And, then, on to King Mob, a fairy godmother dad, and kindly old horribly cruel Tom O’Bedlam, winking, weird, smelly and inconstant.

Dane is imprisoned, made homeless, made to feel dependent and vulnerable in a direct fashion even more than in the casual, common societal ways. He is preyed upon by ritualist soldiers in fox hunting gear. Every rescue carries and implied debt. Every donation or gift or kindness implies a debt. He is hounded.

Hermit and fool. Dane and Tom are unhoused together, an overlap of Old Man Last Year and New Year’s Babe.

Faerie queene = female fairy. Every man a king. Dane, though, he’s Jack. Jack and Tom out in the wilds; slums of London. Jack Tar, a common sailor. Jack in the cards, a knave, a servant, the guy. Jackeroo = a dude. Jack in the green. Jack in a box. Jack o’ lantern. Jack in office. Jackanapes. Jack-a-dandy. Jack-a-Lent. Jack-a-dreams. Hamlet, Prince of Denmark.

Femme-coded. Transphobic. In love with violence. Doesn’t want anybody hurt. Lashes out. Feels pain. Empathetic. Violent. Dane/Jack is never a perfect, balanced little miracle. His learning curve is forever.

It is enough to make a kid want to cut their hair funny and sit on a bucket all day.

We will never really know the relationship between Jack Frost who is also called Dane McGowan, Jack Frost who haunts young Dane, Jack Frost who Dane named and made to represent his anxieties. Why is one Jack Frost intimidating? Or, another? Why does one sometimes speak German?

If one Jack is just some guy, are they all?

Is the towering haunter who speaks with knowledge from the future also just some guy? Jackanapes all the way down to the turtles?

Did King Mob’s cell lose a John and gain a Jack? Jack is often unbothered of binarisms and maybe we should follow suit and, in this case, card.

“And the writer would especially ask the literary reader, who is competent to discriminate between a narrative of facts and a work of fiction, to consider whether it is probable, or even possible, that this work can be entirely the product of the writer’s own brain.”

– The Invisibles, MJ Williamson

All are queer in a queer light.

Dane McGowan. Jack Frost. Three. One. Many. A card in a deck. A Page of Wands.

Could be if we were haunted by our fears and insecurities, but had a little humor about it, with enough distance they would look like Jack. When our insecurities look at us, maybe they see Jack. Maybe they see jack; we tend to anthropomorphize.

Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable says, “No one would ever think of calling the thick-headed male cat a Jack, nor the pert, dextrous, thieving daw a Tom. The former is almost instinctively called a Tom-cat, and the latter a Jack-daw.”

Jack unforgets the apocalyptic snow of the white badge when he had a pigeon’s eyes. The unsourced blood on the wall might be black rain or night or hatching or foliage at an angle.

Jack and Tom. Tom and Jerry. The boy who becomes brave and the old man who became… a bully? Tom O’Bedlam is terrible, when we know his full story, his history. Jack Frost may have kicked a man or blown up a library a little, but he is not so bad. Jack would never send soldiers to murder or seers to die. We can consider thieving criminal all we like, and fault Jack the Giant-Killer with tradition, law, and wit, but Jack is the hero of that story. Tom O’Bedlam, in The Invisibles, can act a likable old man, and he has the compassion and well-wishing of important people, but ultimately, Tom chose self-importance and expediency over compassion.

What’s the angle.

When pre-Jack Dane talks of setting an atom bomb off in his home city, he only thinks it would make a loud sound and excite into action many fire trucks. He is naive and playful. He knows some facts, but he has little scope.

We do not see that, while Tom may be the most powerful magician in the world, and a revered and feared secret leader, he ever gains scope. His reaction to miracles is to crouch down and become smaller and harder. To make it about him and some originating sin he commits that damns the entire universe.

Jack would never.

Jack screws up. We screw up. You just tell your friends you know. You do right. You do right now.

All times are one.

You stay open.

Did I lie to you, when I said Boy witnessed the snow of today before Jack? Do I omit when I do not engage their relative ages? Am I lying when I imply Jack noticed it in recovered memory? Are recovered memories, memories of real things? What are real things?

*******

NEXT: Take People As They Come

Nothing in There is Nothing Left to Say (On The Invisibles) is guaranteed factually correct, in part or in toto, nor aroused or recommended as ethically or metaphysically sound, and the same is true of the following recommendations we hope will nonetheless be illuminating to you, our most discriminating audience.

When Night is Falling. Patricia Rozema, et al. 1990s.

The Invisibles: an Explanation of Phenomena Commonly Called Spiritual. MJ Williamson, et al. 1860s

The Secret Defenders, #16 through #25, and earlier. Tom Brevoort, Mike Kanterovich, Bill Wylie, et al. 1990s.