Patricia Highsmash

Drama, Narrative, What Else Ya Got?

by Travis Hedge Coke

“The root of story is, What do they want, and how will they get it?”

“The inciting incident.”

“Without drama, no story.”

“Three acts.”

Formula is wonderful. Formula is good. Formulas for writing are like recipes for cooking. You have to be willing to acknowledge that there is more than one recipe for making a meal of the same name, more than one recipe using much the same ingredients, that not everyone is going to care for exactly the same recipe, every time, and that the recipe is not the meal, even if the recipe is, on its own, of interest.

“In drama, the characters should determine the story. In melodrama, the story determines the characters.”

– Sidney Lumet, Making Movies

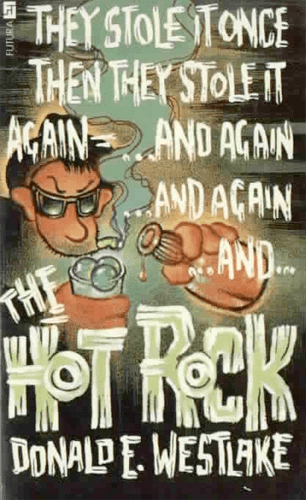

Donald E Westlake’s serial character, John Dortmunder, was originally another Westlake character, the Parker who has been adapted into movies directed by John Boorman and Jean-Luc Godard, portrayed by actors as disparate as Mel Gibson, Jim Brown, Peter Coyote and Jason Statham, and adapted into comics by Darwyn Cooke. With all that adapting, you’d think Parker could be stretched into anything (and anything can, though there would remain questions of how successfully), yet, Westlake found that the central conceit of the first Dortmunder novel, The Hot Rock, was too comedic to maintain the tone with which his Parker painted his world, like a blacklight in a dark room illuminating what is often hidden and how fluoridated someone’s teeth are. It got slapstick to have a stolen item claimed, lost, stolen, reclaimed, lost, for just short of sixty thousand words bracketed between various punctuation.

Westlake’s Parker novels are as formula as a Dortmunder, many of them adhering to a four act, with the third act detouring agendas, but a Parker novel is illuminated by Parker and a Dortmunder novel paints the walls and floor around Dortmunder and then shuts the door coated in wet paint on him, and locks it.

People make drama. People are locked into melodrama.

Not just sometimes melodrama is good. Many times, melodrama can be good as drama or better.

Sometimes, drama is unnecessary.

If you are a horror movie fan, you have experienced your share of people for whom “practical effects” is a holy thing, who insist that more gore, real gore, gore gore goes a long ways to improving a motion picture. But, it is not only that the effects are practical – that is, physically constructed and then executed live on set – or that the gore effects are realistic. It is that they are, often, not realistic. Movie gorehounds might like the feel of someone near them or in their thoughts being grossed out, but there is little praise from those circles for productions like, Suspect 0, because the effects of Suspect 0 are too true to life. They are horrible, but horrible in an understated, actualized fashion, and not human heads which can be peeled apart like a gelatin mold.

The practical gore effects of Suspect 0 are generally not scenes of violence being enacted, but bodies left in cars, body parts collected next to scrapbooks in the hope chest. They lack the movement of change that an impaling or sawing in half of a person involves, and the emotional energy of an assault in action.

The tonal realism sought by these enthusiasts, is not the tone of realism, but the tone of aggression, and mostly more even the tone of a nostalgic aggression. The blood and guts made from corn syrup and condoms equivalent to nuclear family home life scenes painted for 1950s magazine covers as used by trad lifers who neglect to take in that those magazine covers often were wrapped around interviews with semi-closeted lesbians, short stories by communist screenwriters, opinion pieces promoting integrated schools.

The bulk of trad wife TikToks and Instagram videos are fetish material, but the risk comes in the form of most of that fetish being presented not as a parody or exaggeration of potential real life scenarios but real life scenarios.

A difference between gorehounds and trad-lifers, in this equation, being that gore-fans know the other stuff exists. They generally are not making a false history to support their playing card house. That it is a playing card house is part of the fun. A lot of gore fans do not enjoy watching “mean” dramas. They would not want a violent horror movie, even with the best practical effects, to be a drama in the sense that it is no longer a melodrama.

What makes Rob Zombie’s Firefly Family movies, which are a mix of practical and digital effects, a renewable well of entertainment for fans, is that all three movies diverge into fantasy. The first, House of 1000 Corpses, is always a melodrama, always structure-first, a Scooby-Doo episode gone very violent, an episode of The Munsters released only in your nightmares, but around two thirds of the way into the movie’s runtime, as things become too brutal – friends cut up, a father skinned and worn like a costume – the world, itself, twists into dream logic, tunnels beneath the ground, endless recurring terror, monsters lurking lurking cannot wake up. The second feature film, The Devil’s Rejects, plays most naturalist of all, with much sweat and tousled hair and little in the way of movie-pretty, but its protagonists are the baddies, and when things get too hairy for them, towards the end, the soundtrack gives them a heroic overture they have never earned and they go out like legends because they are legends in their own minds.

A worrying question, when the third movie came around, was why is the end of 3 from Hell so similar to the end of The Devil’s Rejects, and why are so many small points repeated? Why revisit the dialogue about who has good or poor night vision? Why, in 3, are a crime boss’ army replicated in a comic in the scene they are about to shoot up? Why are they cartoonishly masked and decorated?

All of the principle three, in 3 from Hell – Otis and Baby from the previous movies, and their relative with the smaller bodycount, Winslow “Foxy” Foxworthy – are beyond their own, personal, levels of handling the reality which has been to them handed. Baby is lapsing into pure delusion before she is even out of prison, and by the time the three decide to drive to Mexico, leaving a wake of survivors who will be forever traumatized and a wave of folks who will be forever dead, they all lapse.

And, that is good. We do not want to see this family of serial killers’ victims happy and thriving or succeeding in life. They are there to die. We do not want to see the family all stopped, shut down, killed, humiliated, or defanged. 3 from Hell makes it subtly clear how pathetic they are, how they are incompetent at nearly anything that is not serial murder, that serial murder ain’t much to be proud of. But, we do not want to dwell, too long, in genuine cruelty, either, real mean. Meanness has to be tempered with irreality.

For all its claim to naturalism, The Devil’s Rejects cannot be Mike Nichols’ Closer, which simply destroys its human beings, or Irréversible (directed by Gaspar Noé). And, even Noé is discovering, as the makers of the Mel Gibson Parker movie did, how much an audience who will accept one version will go if you keep your meanness always up front.

With Irréversible, Noé employed 22 to 36 Hz sounds, in the hopes that, while they will not be heard by audiences, they would upset them physically. Inexplicable nausea and dizziness, non-narrative, non-diegetic, inform narrative and world, as well as story and both drama and melodrama, beyond what we would, maybe, agree to from those traditional methods.

Psychodrama is not horror in the sense of most of the row of horror films on a shelf or a streaming service’s display tier, because psychodrama attacks where we are unwary. The end of Nik Fackler’s Lovely, Still, with Martin Landau and Ellen Burstyn, is excruciatingly terrifying, because we were made unwary. Sidney Lumet’s The Offence has, as its central conceit, exactly as it says on the movie’s original posters, “After 20 years, what Detective-Sergeant Johnson has seen and done is destroying him.”

You can destroy Detective-Sergeant Johnson. You cannot actually kill off Jason Voorhees or Michael Myers.

I cannot say that no one will make you watch Irréversible, but anyone who makes you watch that movie against your own will, is an asshole.

Anyone who makes you watch any movie against your will is an asshole.

And, I cannot say that if you watch any of the movies I have mentioned, you will go un-disappointed – I do not even love them all, myself. I will not promise you that every Donald E Westlake novel will hit a clear drama or melodrama point.

Disappointment is part of life. Doing things you would not choose to, to avoid something you would choose less; unfortunately, part of life. Life is drama and melodrama. Life is narratives and dialogue and ratings boards and sounds you cannot really hear but that make you sick and uncomfortable.

More than one lead in a romantic movie has played their brooding character as an asshole who forces the hand of others. What they do may not affect the narrative of the movie, the story in sense of action to action building to a climax, but it informs the movie. A line reading can change an entire motion picture. Adjectives can alter a novel.

Organic storytelling, if it exists outside prayers and devotionals, is crafting around audience, or shaping to fit performers, editors, solicitors or patrons.

As I write this, I am couching my arguments and playing my hand. I can cheat the cards and because you are not here to watch me, maybe you will not know what I delete and replace or how I pick my examples. It is unfair. And, I play to the same end of not taking the wrong part too far for my projected audience.

There certainly are horror fanatics who take the brutality too far, who indulge specifically in the grossest aspects because they are unhealthily violent in their own thoughts or acts.

There are heist story aficionados who will try to convince you that Donald Westlake or James Ellroy are hard core killer criminals under a veil of respectability, as there are genre fans who are mad when Janet Fitch is a badass or George Romero, Stephen King, Lee Goldberg or another fan favorite are not as brutal in their work or hard-man in their life as the fan may like. Oh, no! cryeth thiseth faneth, This Diagnosis Murder novel is a bit liltingly silly! I suspect George Romero and Rob Zombie might not be the misogynists I was hoping would mirror me!

To work, things are imperfect.

All narrative art – and all art has narrative – all narrative is art – has to have more than event-following-event plot, more than a handful of characters who want something or a moral point to make before the end or it dwindles into forgetfulness, abandoned, as eagerly forgotten as a Academy Award Best Picture, Crash, or Academy Award Best Picture, A Beautiful Mind, once we soberly witnessed how they rejected real life and may have tried to make us cheer for something horrible more crassly than when the Devil’s Rejects met their apparent end to the unearned romance of Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Free Bird coming from nowhere.

To work, things are incomplete.