Patricia Highsmash

Examining New X-Men Pt. 1

by Travis Hedge Coke

From 2001 to 2004 Grant Morrison (The Invisibles, Batman and Robin) and team of pencilers, inkers, letterers, editors and colorists, including Phil Jimenez, Mike Marts, and Frank Quitely made a comic called New X-Men.

Revitalizing the X-Men as a politically savvy, fashion-forward superhero soap opera, New X-Men was published by Marvel Comics as the flagship of a line wide revival.

Part 1

What Came Before

Created in 1963, the X-Men have been an integral part of the Marvel Universe since their inception, and a franchise juggernaut for forty years.

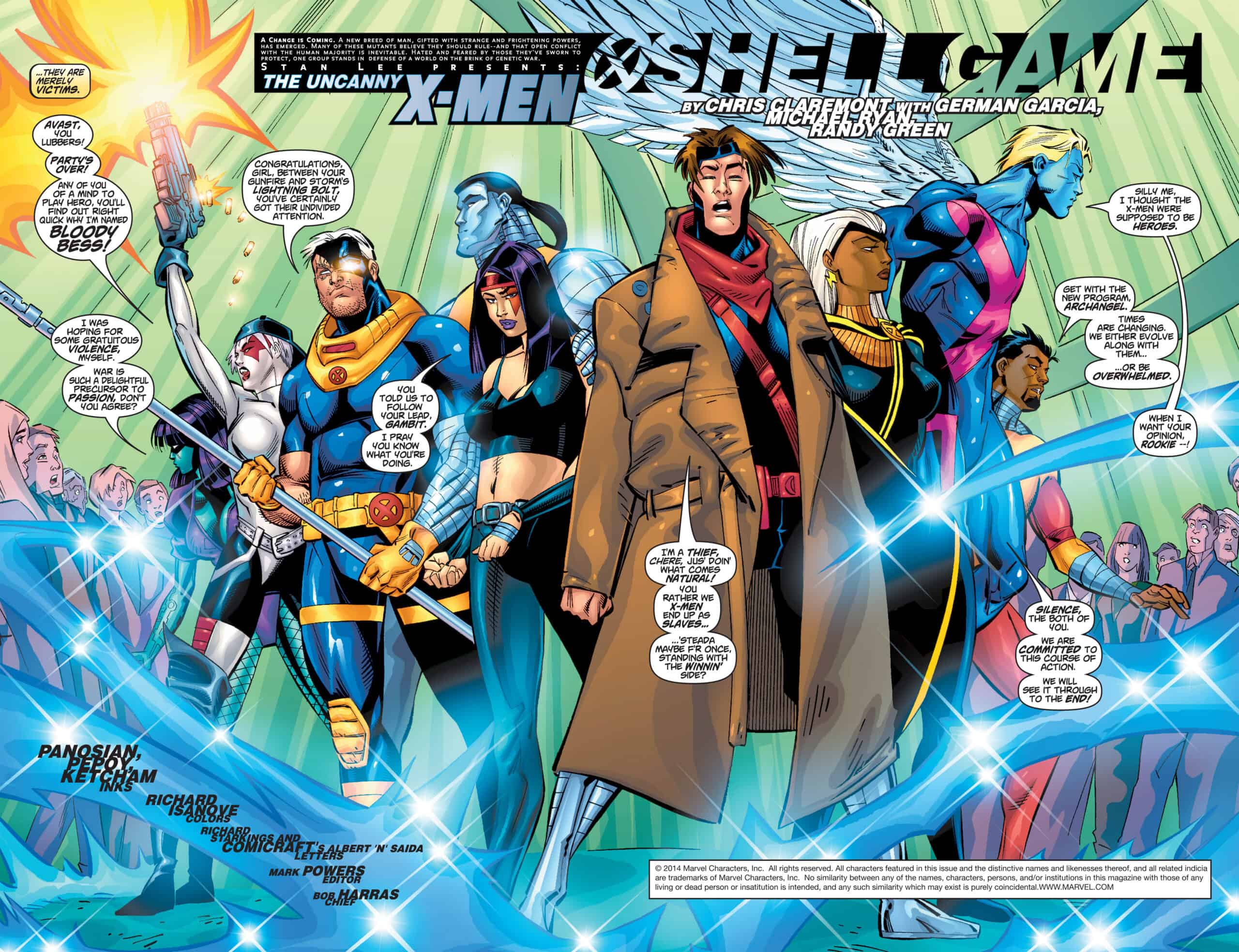

At the dawn of the 21st Century, X-Men comics experienced one of their most critically panned crossovers, The Twelve, the ancillary titles had been revamped under the control of Warren Ellis to no significant increase in sales, and Chris Claremont, who had made the X-Men famous and beloved, returned for a year of monthly issues on the two X-Men ongoing comics.

Chris Claremont, German Garcia, Michael Ryan, Randy Green, Richard Isanove

Cyclops had been possessed by Apocalypse. Colossus died of the Legacy VIrus. Jean Grey was and wasn’t Phoenix. Shadowcat might be a Neo, might be a mutant, might be a mutant Neo. And, with X-Men Declassified, Marvel Comics published an oversized issue of one to two page vignettes that may or may not be true and in continuity.

X-Men had become a hope chest of trademarked names, vaguely defined plots, the occasional emotional touchstone moment, and an increasing pressure to be familiar with fifty years a previously published comics and not expect any payoff or do you understand what you reading until the comic you were reading was at least two years old.

When Grant Morrison, in their pitch document, the Morrison Manifesto, refers to this era as, “septic,” even my love of Edginton and Portacio’s X-Force and some of the sweeter moments of Alan Davis’ run cannot sway me from agreeing.

In ways that cannot be blamed solely on the writer, the artists, colorists, or editorial, Claremont’s return to the X-Men was, issue for issue, arcane, awkward, internally inconsistent, and difficult to parse.

It has now been over twenty years, and we are still uncertain about basic plot elements of that Claremont run.

A six-issue arc by ’90s star X-Men writer, Scott Lobdell, acted as a buffer between the Claremont run and Grant Morrison’s arrival, but even this standalone story seemed outdated, overcomplicated, and overly dependent on unearned good will and familiarity with earlier stories.

Almost completely unacknowledged by any of the comics, the first X-Men feature film had been released in theaters to wild success. Nothing in X-Men or Uncanny X-Men looked, sounded, or felt like anything from that movie.

To be fair, the X-Men movie did visually and narratively reinvent a lot, but while chasing old readers so much, why not an olive branch or a place setting for the huge audience who had just come to the X-Men fear this motion picture?

Traditional talk, Grant Morrison is a risky, non-commercial writer. Looking closely, Morrison is a cannily commercial writer. Not all of their projects are motivated primarily by sales, but much of their big, name-making work has been. This truth is why the comic, and steering the franchise’s comics wing, was offered to them.

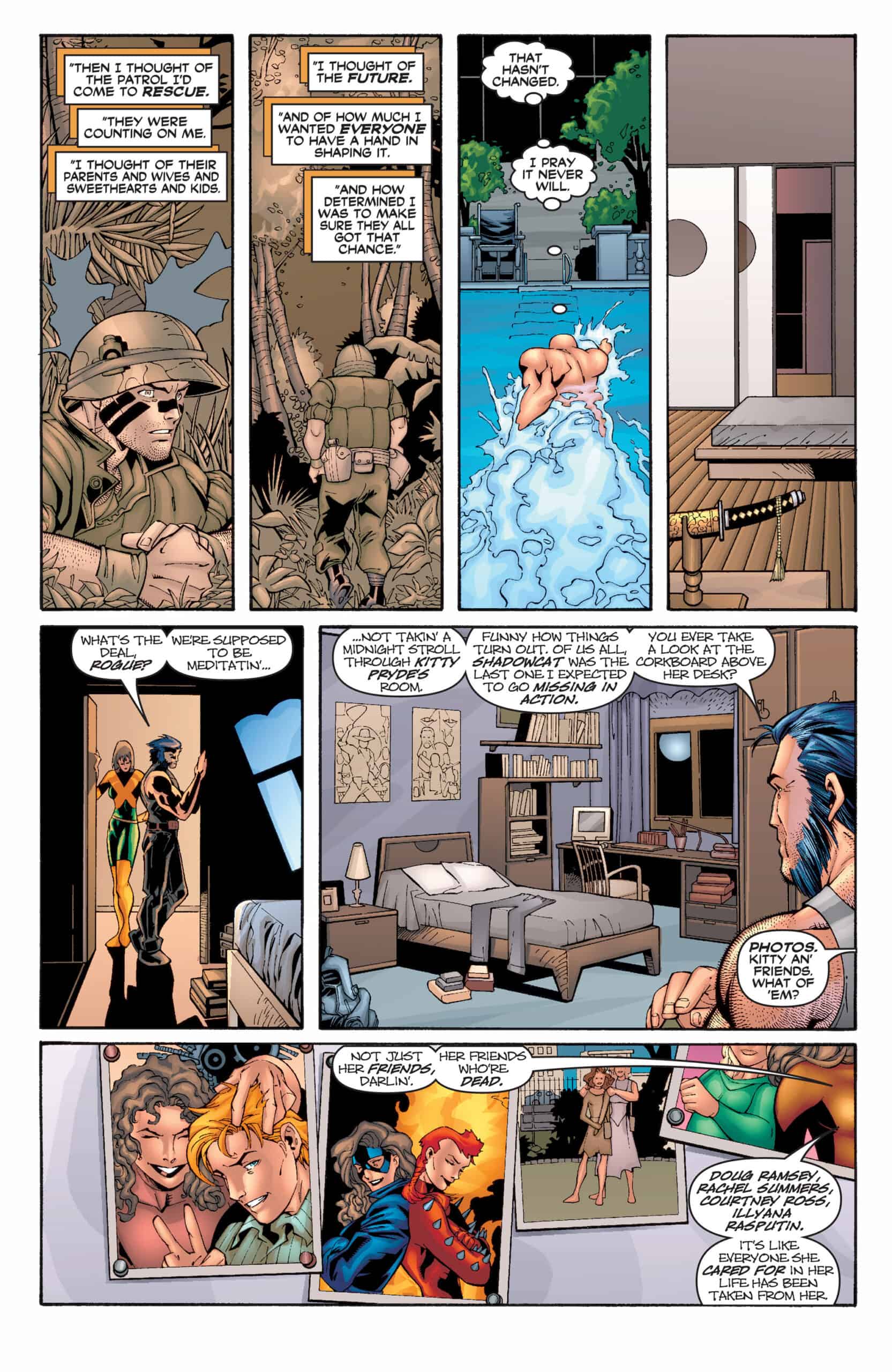

Chris Claremont, Salvador Larroca, Art Thibert, Hi Fi, Saida T!

When Morrison called Marvel, “intensely conservative,” and circa 2000 X-Men, “overdense” and “cautious, dodgy retro,” they were specifically addressing that much of the Ellis relaunches felt like yesterday’s comics, and the Claremont and Lobdell X-Men that preceded Morrison’s first issue had more to do with name recognition and nostalgia than stories with beginnings and endings, without clearly rewarding arcs instead of passive ongoing narrative occasionally punctuated with a feel good or haha moment.

Joseph Harris and Tom Raney’s The Search for Cyclops, while full of declarative sentences and exposition, makes no effort to persuade new or casual readers to care and shows now evidence anyone considers how this comic looks to anyone coming fresh from the X-Men movie. On a personal note, it is also difficult to take as seriously as it seems to want us to.

Joseph Harris, Tom Raney, Scott Hanna

Dream’s End (Chris Claremont, Robert Weinberger, Larroca et al), opening with a chapter titled, The Past is but Prologue!, is made of crowd shots and posed portraits without any clue to who is important, who we should care about, who we should pay attention to. It climaxes with an older man having psychic ghostman sex with a dying woman while someone he used to teach high school literature to, and her adult son, attempt to pull them apart during their psychic ghost sex.

These are smart writers, intelligent artists. There are people who love these comics, as well, but they were too few, too far between.

Bryan Singer and David Hayter’s X-Men, the 2000 theatrical debut of the team and concepts, was the seventh highest-grossing film of the year, reaching a fresh, global audience. The comics offered them nothing that looked or moved similarly. The home media release of the movie, dollar for dollar, made more money in its first week than anything in theaters at the time. The iron was hot for a strike, and instead of Patrick Stewart’s Charles Xavier, the comics had a younger, buffer man, instead of Ian McKellen’s Magneto, the comics had a broad-chested muscleman with strings of spit in his shouting mouth.

Leniel Francis Yu and Scott Lobdell’s Eve of Destruction approaches modernity, by creating a begging-middle-end story arc, but again, we are thrown into characters who will receive no development and for whom we are given no reason to feel emotional over, or invested in.

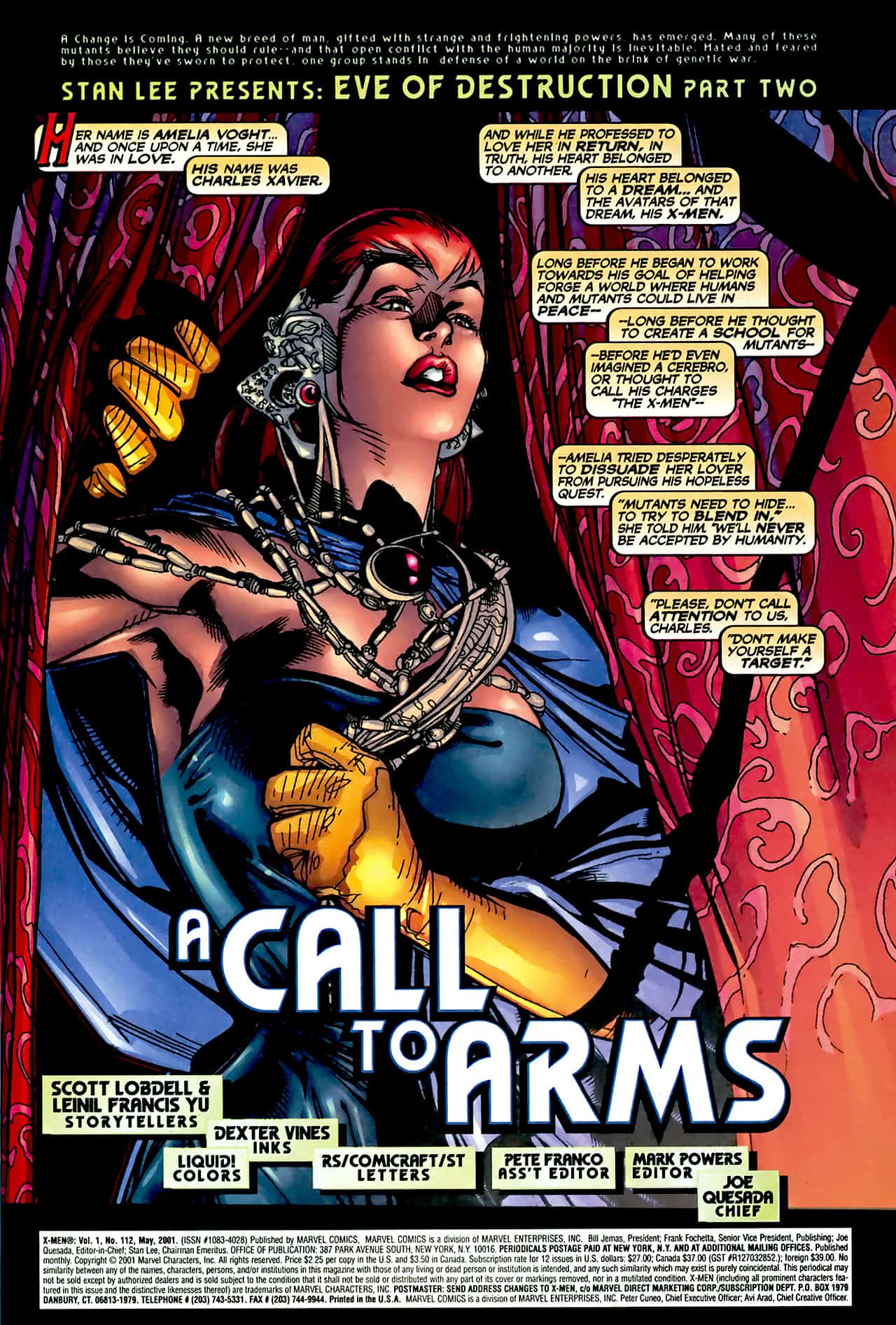

Amelia Voght, a medical professional, serious woman, and someone until this had been wearing a head wrap and conservative clothes since her creation, shows up early in Eve of Destruction in beads, a flashy hair clip, big yellow gloves, cleavage-enhancing strapless green dress, with her reddened lips open poutily for no reason

Scott Lobdell, Leinil Francis Yu, Dexter Vines

In Eve of Destruction, Wolverine is implied to be the not handsome one, between him and Cyclops, concurrent with the growing international lust for theatrical Wolverine actor, Hugh Jackman.

The eleven narration boxes on that one page frame her only as a former lover of a good man she left, a former lover, former lover, former let me check my notes oh yes a former lover.

For all, in a few years, people will be calling Morrison’s Magneto overdone and too villainous, Magneto is here, in Eve of Destruction, marching Charles Xavier through the streets on a crucifix, declaring war on the Earth.

Wolverine stabs Magneto through the chest, possibly killing him, and nobody noticed. Nobody cared. No one remembers.

This is what Morrison inherited, smart people doing work for a dwindling audience with questionable fashion choices, in stories that even super-entrenched superhero fans were not sure they fully understood.