Patricia Highsmash

Examining New X-Men Pt. 16

by Travis Hedge Coke

From 2001 to 2004 Grant Morrison (The Invisibles, Batman and Robin) and team of pencilers, inkers, letterers, editors and colorists, including Phil Jimenez, Mike Marts, and Frank Quitely made a comic called New X-Men.

Revitalizing the X-Men as a politically savvy, fashion-forward superhero soap opera, New X-Men was published by Marvel Comics as the flagship of a line wide revival.

Part 16

Authorship, Ownership, Brinkmanship, Relationship

The original run of X-Men was not a financial or especially a critical success. Within a few years, the title was a house for reprints instead of original stories, a condition that continued until the cast and concept was almost entirely reworked by Dave Cockrum and Len Wein, joined after a couple comics by Chris Claremont, who subsumes that first bump and new team/new concept/new agenda into the Claremont Revolution… and, do you realize this means that the Claremont Revolution then begins without Chris Claremont? This surprises me. Every. Time. (Editor’s note: although it is said, rumored, that Claremont had a shadow proof-reader/plot-brainstorming role in that first issue, that was, otherwise, Claremont free)

Most of what we know is a myth or a sell or a misremembering. Scott Lobdell being hired to write X-Men because he was the only person to say ‘Yes’. Chris Claremont leaving X-Men after seventeen years because he had bad blood with Jim Lee or Whilce Portacio. Whether or not the X-Men as a comic and concept exists because Doom Patrol was already in the offing from Marvel’s competitor and distributor, DC Comics, is something that will likely never be truly settled. We don’t know. Nobody alive knows and can speak definitively.

Relationship

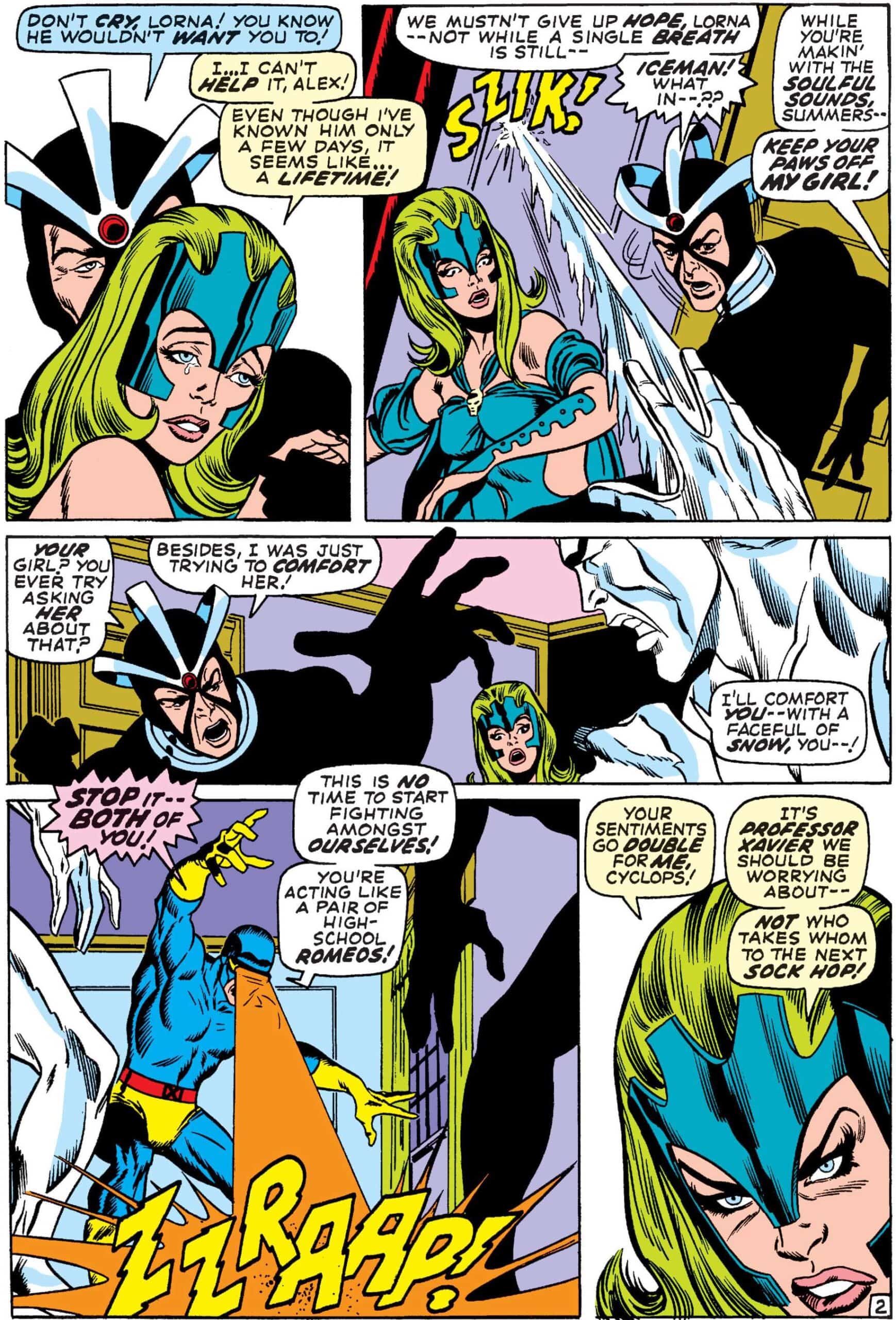

Roy Thomas, Neal Adams

X-Men has been more soap ensemble than superhero team at least since Roy Thomas and Neal Adams were making the comics. The earliest romance teases, the question of whether Jean Grey would date any or only one of the male student’s at the Xavier school, was never more than background chatter, minor characterization. The Adams and Thomas comics kick it up a notch with Iceman/Polaris/Havok, a real and dyed in the wool love triangle. With Claremont and his succession of sex-from-the-pencil artists, shipping sexual or romantic relationships has been a favored pastime of fans and readers, and X-comics have encouraged and thrived on fan-supposition and the perception of every dynamic as romance or sex or both. Audience engagement, audience participation, has been paramount.

Coupled with the target readership age of ten to twenty, X-Men and related titles make an incredibly apt study for queer coding, post-laconian sexuality, and general old coming of age. A tradition of male-gaze to the presentation of queer-coded entanglements of women cannot be ignored, but it is presented to the very real queer female audience, and as it progresses, queer female and nonmale authors, working on X-Men comics, and in particular, the burgeoning pubescent sexual awareness of youth.

As much as I, a case study of me, am unnerved by the consistent sexualization of teenagers, including decades of emphasizing teenage bodies in underclothes, from the group in their undies scenes to the frequent use of panty shots, I cannot separate that from the positive potential these same elements have had in allowing audiences to come to further personal sexual awareness and maturity.

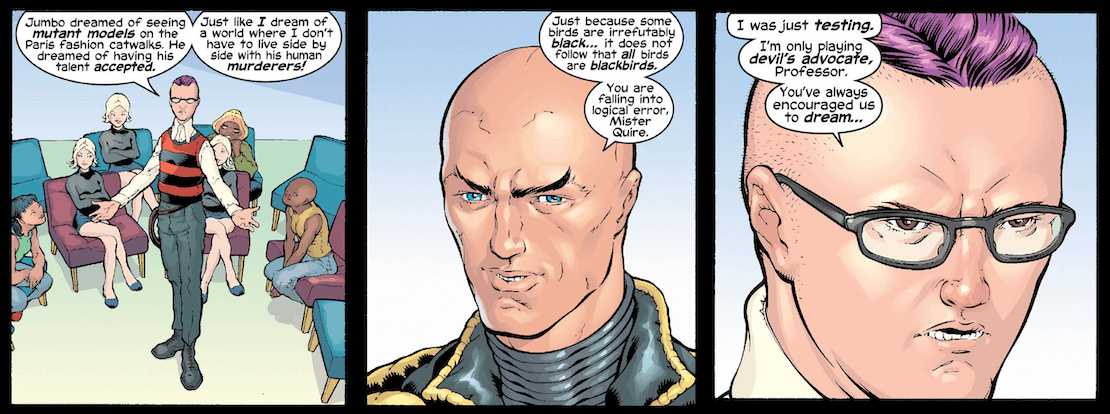

New X-Men is one of the horniest runs on an X-book (this is saying something!), and one of the strongest focuses on adults and teenagers, but New X-Men is also notable for being less eroticizing or sexualizing of the teenage bodies, while permitting them access to condoms on panel, for discussions of sex and pregnancy that are far more direct than earlier similar conversations of those in X-related comics since.

The difference in visual portrayal and in sexual eagerness between the Stepford Cuckoos in New X-Men and after is, to be kind, dramatic.

About as soon as Grant Morrison has quit and wrapped up their New X-Men stories, the young women in short skirts bending just so return, as inevitable as sunrises.

Authorship

In recent years, we have seen popular entertainment at the broadest levels embrace the concept of multiverses (in this case, popularized by Michael Moorcock, a huge influence on young Grant Morrison who has had only bad things to say of Morrison). The cinematic and televisual universes of Marvel and DC Comics’ properties have become multiverses of interlinked, fully operational fictive Earths and universes, without a general audience scratching their head or running in fear, while, just before New X-Men launched, the most-general of general audiences chose The Matrix over The Thirteenth Floor or eXistenZ, in part prominently after The Matrix’s advertising campaign spoiled the movie’s central reveal before the movie was even released, ensuring comfort and no room for anxious uncertainty.

Transgressive retelling (in the vein of Kathy Acker, Anne Sexton, and Jack Kirby) and the hybridization of genres and eras (as once proposed by Kirby as a soon-to-be-rising-trend marking the early 21st Century) have become common in entertainment and easily digested by millions of people, while, at the time of New X-Men, they could be seen as exceptionally geek culture specific and difficult or off-putting to broad audiences. New X-Men utilizes these techniques in refined and subtle fashions, so that the recapitulations and remixes bothered even some deeply-immersed geek audiences, but as time goes on, I imagine them making the comic more accessible to more people, never less accessible or less relevant.

Super-consistency, never a wholly articulated or overly serious replacement for inter-story continuity, is the barriers between fanon and canon being erased, the collaborative nature of comics being brought out not only in terms of penciler, writer, inker, et al, but comics’ authors as an audience and comics’ audiences as authors. Fanon, fan canon, is a suppositional and subjective canonization of interpretations, as opposed to easily demonstrable explicit content.

Super-consistency, like fanart, is sometimes treated as antagonistic to professionalism and disrespectful for authorship and audience capacity, but like fanart, the dead opposite can also be true. Super-consistency respectfully acknowledges that an objective and concretized chronology, as well as causal, measurable continuity, cannot nor will ever be sustained in the X-Men comics or the larger Marvel Universe in which those comics are entrenched yet sometimes distanced in.

Ownership

There is a podcast episode which focuses on Grant Morrison’s proposal, the Morrison Manifesto, to criticize them for not making things accessible to new audiences or drawing in movie fans, pointing to things like evil twins and evil Magneto, which for me, says much more about the podcast presenters and the audience they represent than either the hypothetical general audience or the audience who did show up New X-Men every issue. Evil twin should not be a concept impossible for anyone to grasp, and if it is a concept too silly to embrace, X-Men, or indeed, any superhero comic that has been serializing since the 1960s, is probably a very poor port to cast anchor.

Yet, I too, am not a general audience.

New X-Men casts a wide net when it comes to references, so there is a chance that different allusions would hit different sub-audiences, a reference to earlier X-Men stories for this type of person, Diabolik or Captain Britain or Max Ernst for other types. Monster Magnet or the Monkees.

Is the Tintin who probably dies in New X-Men a parody of Hergé’s famous Tintin, a child inspired to adopt the look of the famed fictional character, or did Igor Kordey just draw Tintin into a scene set in le tunnel sous la Manche for a laugh? Any of the three may appeal to different readers, while still more may stand to at best be amused by the unique hairstyle and charming profile. And, all four of these comfortably skate the rim of legality.

Igor Kordey, Grant Morrison

An author or company can own the trademark on a character, the copyright on a story, but no one other than you can own the story you read, the entertainment you have taken into yourself, because it is, after and forever, then, inside you. We own the stories once they have come into our minds, stories that are never identical to the stories recorded in media outside us.

We can annotate, decimate, draw on or deface our copies we have purchased and, of course, we can steal copies we have not (we just know we should not).

I can draw diagrams and make lists to explain how Emma Frost and Jean Grey are both the gnostic Sophia, both sapphics, both sophists, and, of course, superheroes, but I do not need to in order to know these things from the comics. I did not have to consciously or carefully draw them out from the comics.

“I don’t need telepathy or a psychology degree,” says Wolverine, “I watch people. I stalk ‘em. They got habits.”

Wolverine intuits with agenda, where Cyclops or Charles Xavier might consult an authority.

Every comic inside your head is yours.

Brinkmanship

The Marvel Universe is a simulated world, with simulated geography, architecture, politics, fashions, weather and climate, in the same way that The World is a simulated world in New X-Men, a circular “square mile” of domed space in which the speed of time is under artificial, external control, as are laws and culture. The X-Men universe is a subsection of the Marvel Universe, the same physical, chronological realm, only emphasizing or isolating the aspects that directly concern X-Men-related characters or mutancy as a concept or social reality.

The World only shows up physically for one arc of New X-Men, Assault on Weapon Plus, aka, The World, The Flesh, and The Devil, but conceptually it reaffirms the concentric rings of artificial worlds, model worlds, that comprise New X-Men, including the Xavier Institute, the nation of Genosha, the 15o-years-from-now future, and the Mutant Town neighborhood, as well as New X-Men, itself, as a semi-autonomous built world distinct and also part of the overall x-books and the Marvel Universe.

An arguably forced-synanthropic world without mutant humans or animals which are not functionaries of The World’s culture, The World contains children and families subject to summary executions, expungements, and military drafts, as well as birds with cameras in them and whales transformed into airborne, street-patrolling police.

The World is a high-science in-world attempt at realtime, real place fan fiction, speculative fiction taking that central (fictive) notion, “our world, but without the real world thing (mutants).” From there, the fiction grows and is curated, the politics crafted, the social order and expectations structured. Like any fiction, nothing simply happens, nothing is necessitated by the facts. The scientists and politicos who believe they are the authors of The World create what they want or what they believe is best serving their ends.

The World begets, as its final product, a world to be abandoned, and the toy line it produced. The wrestler philosopher – no, not Plato – Ultimaton! The branching-brained giant with endless henchmen, The Hunstman! The ninja genius and their semi-sibling support nervous system, Fantomex and EVA! Action figures with a playset placed in orbit around the Earth, believing themselves to the frontline in a fight against an invasive foreign culture, but in reality in action solely to make a show.

The denizens of The World, like the denizens of the world The World is in, are toys made to break, toys made for rough play and for shelf display. EVA or the Huntsman, Emma Frost or Jean Grey, they exist to be limited-articulation plastic or high end renderings. Idea-complexes with faces and hands you can hopefully make hold the accessories they come packed with.

Authorship

Dialogue is not thought nor truth, and in comics about hypocrites and telepaths, thought is not sacrosanct honesty. To read any X-Men comic and believe every character is totally honest and absolutely aware and a fair judge is a road to disaster that too many fans take like it’s the expressway.

There is, within the X-Men stories, no omniscient and totally honest narrator. Every character who is vastly knowledgeable is likely a liar. Even the unspoken omniscient narration of place names or times have been shown to be incorrect, sometimes containing misspellings or entirely incorrect locations or timestamps.

Art and script, dialogue and visual, one comic and another in the same continuity, may disagree or present concurrently incompatible scenarios.

Our favored critics, trusted braintrusts, beloved artists, writers, brands and publishers are anchors and handholds, ports in any storm, way station and weigh station. Lists of names, arrays of rated and formatted entries help assure us on our way through the consistent uncertainty of knowing we have to make our final decision about all our interpretations.

Grant Morrison, Frank Quitely, Tim Townsend

While becoming fully enmeshed in the true fairytale of comics, one must acknowledge the unreliability and massage the reality-tableaux being believed in.

Relationship

Even characters agreeing with one another, cannot a reality or truth establish. X-Men comics, in particular, New X-Men, are formed and polished with simulation. With emulation and emulsion, New X-Men took the pre-established rules of psychically-formed physical matter, multi-bodied and disembodied intelligences, false memories, psychic constructs, retroactive continuity and gnostic mysticism that had begun to be imbued even before Claremont, and amped it to a central unreliability of the world extant.

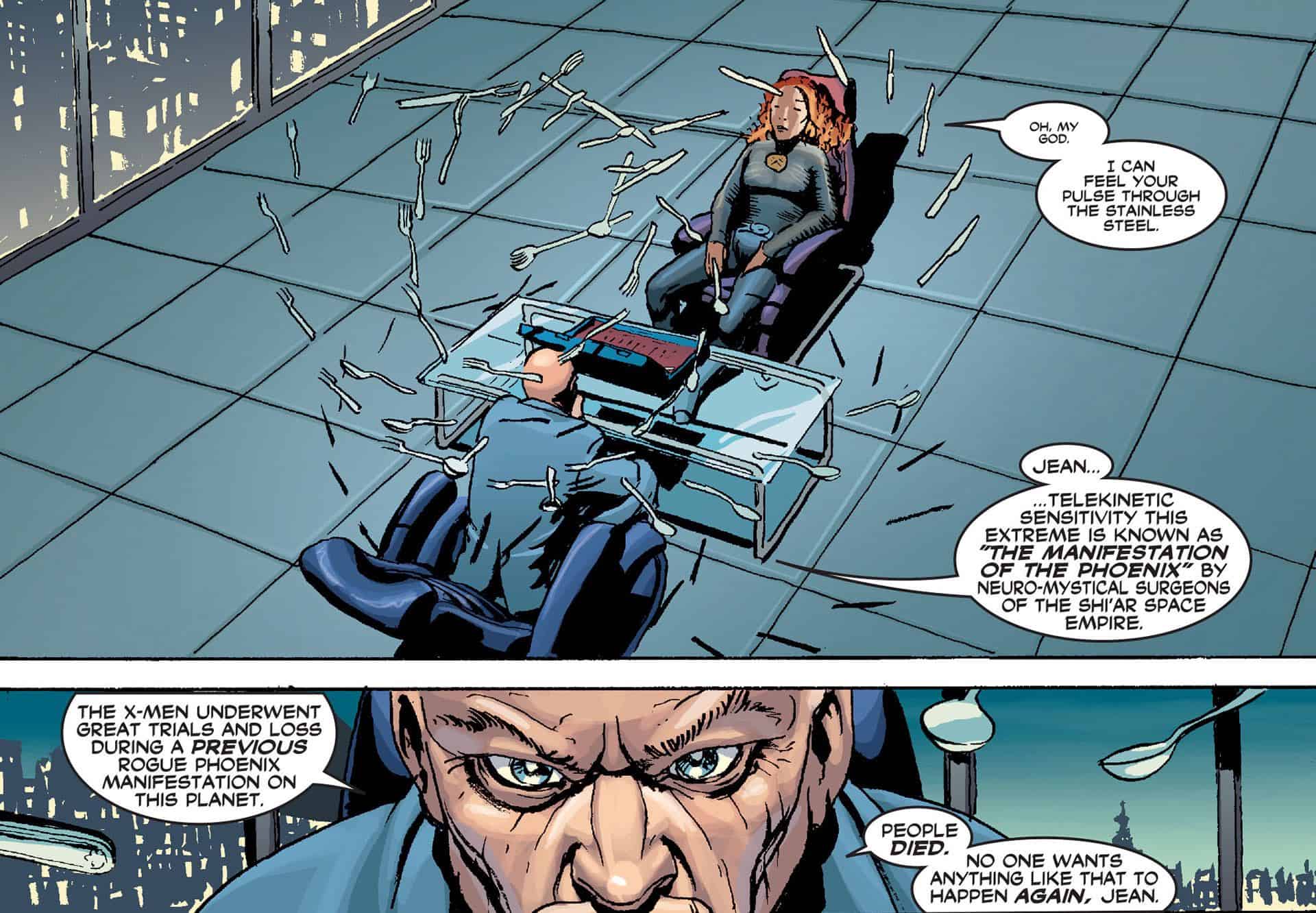

The script for one issue, reaffirms Emma Frost’s angling for Cyclops as, at least in part, actually a tête-à-tête with Jean Grey, and during Grey’s discovery of Cyclops’ and Frost’s extramarital affair, it is impossible to be sure when we are in a mental projection or objective reality, when we are in Grey’s or Frost’s mental projection, or Cyclops’, or the Cuckoos’. Over the course of two issues, the sense that there can be a definable, confirmable objective reality is muddied and turn like a shoe lost in heavy rain on a busy highway,

By the end of Grey and Frost’s discussion of the Cyclops/Frost affair, we have lost objectivity, ourselves, and most readings, will never question whether or not we have rejoined a reality that is not a shared psychic projection, not even when later arcs, such as Here Comes Tomorrow, appear to be validly taken as dreams or fantasies, or when a statue of Charles Xavier weeps blood.

Cassandra Nova, at least for the first forty-something years of her life, believes that the world – the universe – consists of herself and her brother. By Here Comes Tomorrow, when Cassandra appears to address we readers directly, it is not out of the question that she is addressing, rather, her brother, now a disembodied intelligence as she has before been, now so enmeshed in the world as to be the world, and what more apt world than one where his dreams came horribly hugely true and his sanctified statues cry blood?

John Paul Leon, Grant Morrison, Bill Sienkiewicz, Chris Chuckry

In a similar fashion, though easily forgettable in the moment, as our blood rises, the existence of Sublime and the effects of Sublime are a good occasional reminder to check the melodrama of X-Men comics and revisit the events and characters knowing there has been a prolonged (longer than human history) and consistent subtle, secret, external pressure to melodramatic conflict within all non-mutant human beings, and within some mutants.

Sublime is the external need, in our world, for the characters in their world to fight all the time, but within their world, too, Sublime is a very real, very concrete motivator of conflict that the characters, themselves, are almost always ignorant of. In most stories, as in many real life systems of belief, what Sublime is in terms of actions, is most often a metaphysical, purely intellectual or spiritual ideology, but as a physical being with a personality and dialogue, we are and the characters in the stories are pressed to address Sublime with more reality, regardless of whether this is sensible.

The conflation of physical and psychic reality and the personification in Sublime give us science fictional anchors into heady metaphysical and ethical territory, but simultaneously lend us an ability to distance ourselves and our self-reflections from the X-Men characters and the metaphysics of their world. We can really look on them as models, which of course they are, without greatly ruining or distending our temporary indulgences of them as a world equally valid and engrossing as our own.

Ownership

In the context of New X-Men, characters are consistently not acting totally of their own freewill, and can never be certain they are ever acting of their freewill, due to beings such as Sublime, who lives inside everyone and plies them with pressure and motives, telepaths and psychics like Charles Xavier or Jean Grey, and by extension, reality warpers, brainwashing cults and government agencies, and hard reality resets.

Frank Quitely, Chris Chuckry, Grant Morrison

Putting all those momentarily to the side, it is imperative, though rarely dealt with directly by audiences, to admit that no fictional character is self-determining. Any time a character has defended a suspect choice, whether in fashion or romantic partner or mass murder, they did not actually make any choice.

The confluence of distanced awareness and enmeshed sympathy for fictive worlds is a backbone of other Grant Morrison comics, from The Invisibles to The Multiversity and Ten Sounds That Identify a Kind of Person. Experienced by all experienced readers, this healthy balance provides a frisson that turns all entertainment into edutainment, and opens the reader to healthier ways of examining real life experiences, from conflicts and frustrations to pleasures and surprises. Meditative and deescalating without any loss of compassion or empathy.

We get mad at characters for decisions real world creatives or their bosses made for them. We are angered by the decisions of authors and artists affecting or directing fictional characters as if they were real people being jerked around or maligned. We defend our own politics and aesthetics by rooting the argument in the actions or opinions of fictional people.

Brinkmanship

The world on the page is the way station of fiction. The world on the page is the weigh station for our ethics.

Our aesthetics are our ethics. Ethics our our aesthetics. Aesthetics and ethics shared become morals. And, that is moral order. Moral order: moral causality.

The tighter we try to wind this, the more the braid frays.

Grant Morrison has said that learning to really hurt characters was a hard leap for them to make. No character has enough life or lifeblood to really hurt.

It is all simulation. The desperation of lived lives.

Or, it is realer than what we agree on as objective, nonfictional reality because fictions have enough lifeblood to hurt. Because the worlds have an intended and a perceived moral order. Because they have authors. And, editors. And, owners. In those, a certainty, even if it is a certainty of who we can blame.

To count on has fewer letters in common with “reliable” than with “accountability”.

Ownership

Especially when it comes to corporate-owned, work for hire, or purchasable ownerships, author and auteur cannot be fully synonymous, but we increasingly operate in a world where it cannot be presumed that any work – including entertainment and art – is not purchasable or claimable by a non-auteur owner or a non-author owner.

On the frightening end, this means that, healthily, a comics artist or writer working for a company like Marvel or DC Comics must understand, in a post-Watchmen, post-Friedrich-Ghost-Rider world, their contracted freedoms or structures are easily subject to worst possible case scenarios. Niceties are niceties only in name. Elektra Natchios was resurrected because someone thought her visual would make a good action figure, and any handshake promise to not do so was just that, a handshake with a person. Chris Claremont was not invited to the premiers of any of the early X-Men movies, being present only as a plus one.

Outside of comics, the rights to HP Lovecraft’s and ER Burroughs’ bodies of work, and concepts directly derived from those works, have been regulated by intensely litigious controllers with very little actual legal room to stand. Same, the owners of Sherlock Holmes. The Happy Birthday song. Legal, sometimes, is a matter of who can last longer in court. Or, who even wants to step in court first.

In Fashionable Nonsense, Jean Bricmont and Alan Sokal – a philosopher/physicist and a mathematician, respectfully – take psychoanalyst and lingual theorist Luce Irigaray to task for a quote attributed to her with no clear source and no evidence, making light of her theories on subtle and corruptive effects of sexism on common and critical language and our approach to everything from physics to economics.

It is presumptuous of me, but I am going to presume anyway, that they fall into this fallacious bout of critique because of the kind of corruptions Irigaray has spent her career illuminating. Richard Dawkins repeats and reaffirms the criticisms of Bricmont and Sokal – again, criticizing something that is not attributable or meant – for the same reasons. And, other men, regardless of education or degree, with and without, will repeat and reaffirm, because the reaffirmation is neither that Irigaray is wrong, or that the statement she never made, that “E=mc2” as an equation is subject to sexism, is wrong, but because by attacking and shouting down the statement (with no stater) and the misattributed theorist, Irigaray, they are both awarding math and science and re-limiting them to male domains. It is her hubris to exist as a woman that is being taken to task, her hubris to think she can understand or even discuss or consider.

My dear readers, this is X-Men fandom and too much of professional X-Men.

Authorship

We look for authority. We search out authority to abide, to lean on, to bolster ourselves, to fight. Auteur and camera-pen theories, anxiety of influence, the affective fallacy, New Criticism (and TS Elliot), and the self-righteous aggrandizing of the New Atheists (Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, Sam Harris, and Christopher Hitchens) are gropes for an authority, even if that authority needs to be made up like sod crammed in old clothes to ward off crows or a doll in a cradle in the manger scene of a children’s play.

We look to reliability in names, give names and people responsibility they may never have held nor asked for.

I call this run on New X-Men, “Grant Morrison’s New X-Men,” and certainly they are instrumental and central to its design and construction, but they never work alone, and much of what I love about the comics was not generated by Morrison, but by collaborators or in collaboration wherein it is beyond me to assign a singular authorship. I, by large, ignore the handful of comics published as New X-Men after Morrison has left. They are no less comics and no less New X-Men issues, but it is not solely the absence of Morrison which drives me to abandon them when I talk New X-Men.

Those comics – drawn, written, handled by normally more than competent creatives – operate in a phase of bizarre ignorance and contradiction that make them feel forever completely separate. No attempt has ever been made by Marvel Comics to pair them again in any collected edition.

Do I look to Morrison as the author and authority? I cannot.

I look at Morrison as an author, never the owner in a legal or financial way, but always the owner in the sense of pwn. Morrison holds the best cards and is, to the end, the one who can see what is on the cards. They own the table while the game is being played and afterwards. The followup stories, still nominally New X-Men, evidence for us all that they do not know what is on the cards or what order they can be played in to win. Xorn is no longer a guise, but a person. Then, two people. Cassandra Nova is now to have never been the student, Ernst, attending her brother’s school and in some impossible future to be the headmistress, herself.

Relationship

An important step in modern theory is that our individual genders and sexualities are, indeed, individual, and that our tendencies and preferences in our entertainment and fantasy as as much a part of those identities as are our socialization or sexual engagement with other human beings in person. Our core being is inherently self-reflexive, self-concerned, and we socialize with our fictions as much as with our nonfictional physical reality. Not a flaw in people, but a boon to us in internet, globalized, or quarantine ages. As with every character in New X-Men, obsessive individualism is death, but in their world death will always be impermanent because their world is a learning module, a set of interlinked, semi-looping models for us to take from.

Dave McCaig, Igor Kordey, Grant Morrison

We too, face over-individualism as stagnation and pain, but like the New X-Men characters, all of us have an inherent solipsistic quality, an in-built awareness of us/not-us, and a need to work on ourselves.

A fiction cannot force our hand into dramatic action. A movie cannot make one murder. A story cannot make one marry. A song cannot force you to drive cross country and throw your savings out the window one dollar bill at a time as you go. But, stories give us the measurably same emotional responses as non-story/nonfiction life. Art and entertainment stay in our memory in ways no different from physical waking life. The moral order, the moral causality, even the physics and law we ascribe to is tempered and formed by the fictions we know as much as the nonfiction.

Both the creation and the indulgence in fan-made art, fan-made fiction, fan speculation may be codified differently, but are, in terms of socialization, alongside gossip, conversation, rumination, and celebration just as of anything from objective waking life society.

In the same way that comfort objects were traditionally scene as transitory, and in fact called, “transitional,” fan-narrativizing like fanart or fic were supposed as transitional stages to either real (that is, paying) art or writing. That fan discussions and fan speculation would give way to academic or professional criticism or something more respectable, like La Traviata trivia or football stats. And, even those needed to be justified or brokered capitalist lubricant.

Comfort objects – which again are not by necessity physical objects, but can include songs, characters, videos, and fictive worlds – are both ungraspable and the first things we grab for in crisis, bonds that are formed or reaffirmed at any point in life. Most importantly, healthily formed at any point in life.

Brinkmanship

Ultimately, comfort objects, as with all objects, are not physical items but what we desire in them and what we ascribe to them in order to desire them, even if the desire we have for them is to reject or destroy them. It may be, far more than we would likely wish to admit, that much of the desire, much of what we desire, is to reject or destroy the ephemeral and yet very real objects. Because object is aim, a priori.

Slavoj Žižek’s address of the MacGuffin as objet petit a – the object of desire other – and objet petit a as MacGuffin expands to fanon, to fanart, to fan sense, both a perceptual and interpretive sense.

For Jacques Lacan, jouissance is almost the pursuit of pleasure/comfort.

Roland Barthes positions jouissance in tandem with pleasure, so that pleasure is conducive to sweet or reader-friendly media and jouissance to hot or writerly (that is, critical) media.

For Hélène Cixous, jouissance is, itself, pleasure, but pleasure at a transcendent, mystical level, particularly in defiance of systemic suppression.

Grant Morrison, Igor Kordey, Dave McCaig

It is Cixous’ jouissance, and also Derrida’s, which allows phallicism to be shown as a cultural supposition, and ultimately a tender and brittle one, needing to be consistently and constantly reaffirmed, armed and armored, or it collapses, and it is from there that Cixous can ascribe both women and non-women to places of note in women’s achievement, women’s existence, while transphobes can use the same brittleness of phallocentrism and the phallus to erase women from women’s achievements, the existence of women by way of their refusal to admit the brittleness is due to a fundamental existence of the phallus only as cultural supposition.

Which is a long, winding, but articulative way to say something that is illustrated, with New X-Men, by the supposition of many readers and critics that the man in the snow globe of semen with Charles Xavier’s mother is Xavier’s father, Brian Xavier, despite looking exactly as Charles and nothing like any representation of Brian Xavier seen anywhere in any comics at all. Those readers are self-selecting a brittle suppository over the transgressive but earnest actuality of Charles Xavier’s place, in that vision.

Uncomfortable, but, that, my good friends, is how we read lives, and how we read New X-Men.