Patricia Highsmash

Examining New X-Men Pt 3

by Travis Hedge Coke

From 2001 to 2004 Grant Morrison (The Invisibles, Batman and Robin) and team of pencilers, inkers, letterers, editors and colorists, including Phil Jimenez, Mike Marts, and Frank Quitely made a comic called New X-Men.

Revitalizing the X-Men as a politically savvy, fashion forward superhero soap opera, New X-Men was published by Marvel Comics as the flagship of a line wide revival.

Pt 3

New as Brand

” I was thinking of everything that had been done before and trying to do an updated version of it,” New X-Men writer Grant Morrison told Tom DeFalco in 2006.

A common apologism is that New X-Men was simply too new.

“Cold open, turn the page, you’re into the title. Nobody had ever done this before,” Al Ewing told marvel.com in a 2019 retrospective. “It felt new. It felt audacious.”

Grant Morrison, Frank Quitely, Tim Townsend

New X-Men #115, Frank Quitely and Grant Morrison’s second issue, ends with a plane crashing into a building, in an act of international terrorism, hitting the stands barely a month before the 9/11 tragedy in 2001. The issue that debuted just over a week after that real life terrorism, #116, explores the after effects of such horrible actions, with rescue workers walking equally on hopes and futility in the wake of loud and violent murder and a nation shaking from harm.

In the early 2000s, New X-Men felt immediate. Modern, futuristic, daring, with an ability to use words like ‘gay’ casually and without marking it as a very special issue. But, on close examination, as with much of Grant Morrison’s work on corporate-owned superhero comics, most of New X-Men consists a characters created before Morrison came onboard, concepts and dynamics woven into the X-Men before Morrison came onboard, leaving most of the characters fairly close to where he found them, just more obvious, more now.

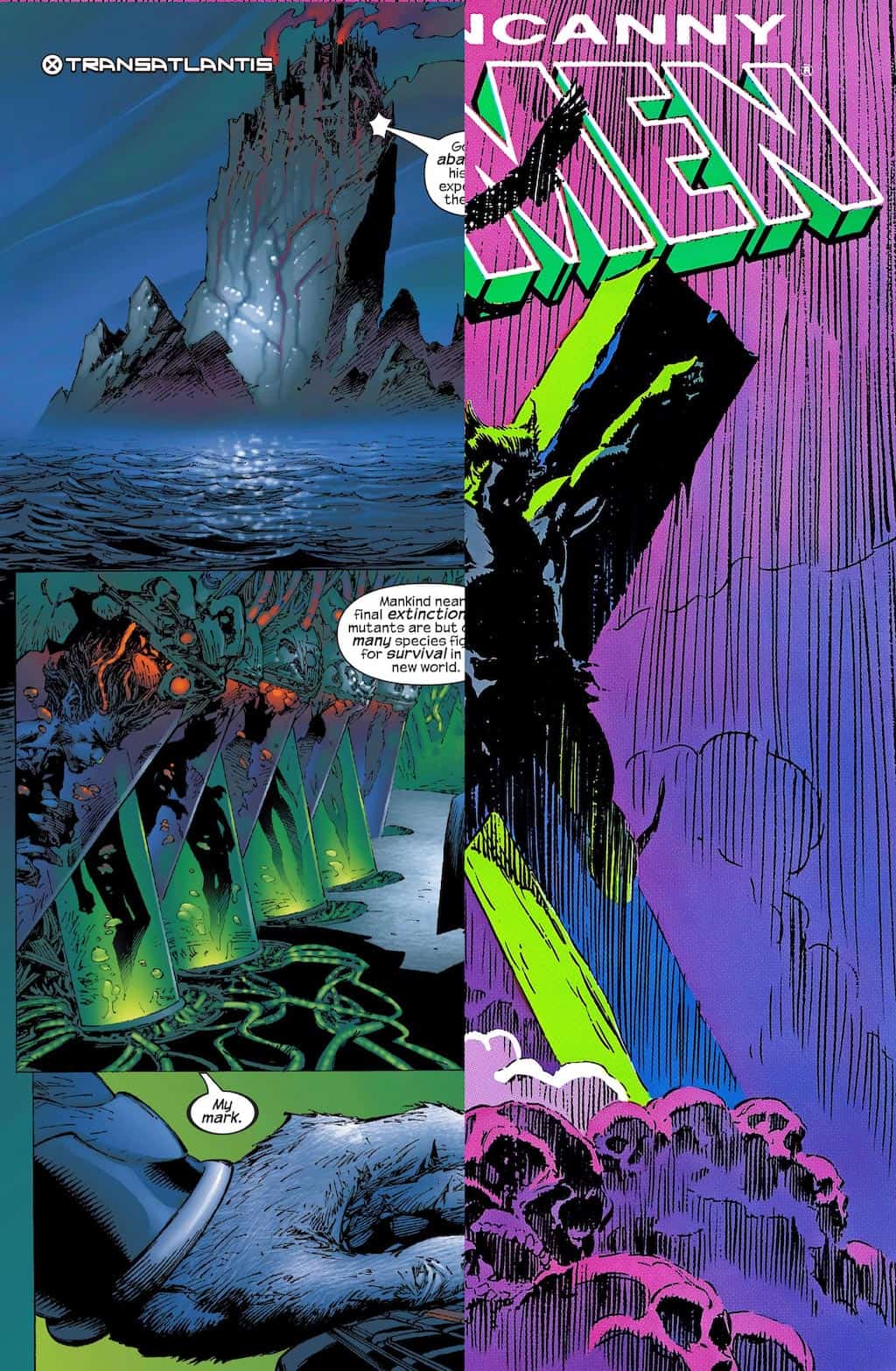

Morrison designed the series’ logo so that it looked modern but also could be inverted and say the same thing as upright.

In his Supergods, Morrison says, “I chose to cast the X-Men not as the victims ‘feared and hated’ by a world that refused to understand them but as out-and-proud mutant representatives… New X-Men would be about the dawning of a future with new music, new dreams, new ways to see and live.” But, at their own admission, it was also about, “The positive and negative aspects of geek culture hitting the mainstream,” foreseeing the increasing blurring of geek and mainstream that has informed everything from the Marvel Cinematic Universe to nature of several streaming services and how pop media and geek media is approached by modern, 2021, news outlets.

Ewing praised the presentation style, the “Minimalist Wolverine; minimalist Cyclops and Jean Grey.” Morrison would reflect excitedly on both the Classicism of Frank Quitely’s designs and the Romanticism, the “almond eyes” and beauty of Marc Silvestri’s work on the Here Comes Tomorrow arc.

Often referenced as one of the lasting effects of New X-Men, Emma Frost’s turn as a superhero and a teacher on the side of right, Frost had been teaching as headmistress of the Xavier School for Gifted Youngsters, for half a decade’s worth of comics before Grant Morrison wrote his first issue of his run, including the entire original eighty issue run of Marvel’s Generation X.

The changes that may feel radical, largely are cosmetic (Beast’s new catlike appearance), a matter of reasonable extrapolation (the mutant nation of Genosha has enough mutants to form a reasonable national populace), or in the pre-built tradition of earlier X-Men comics (Emma Frost’s secondary mutation).

Dismissing cosmetic changes as lacking affect is a mistake. It is a misstep to react to the impact cosmetic or stylistic execution has on an audience as premature or unworthy. Impact and resonance are paramount, regardless of how they are achieved.

Morrison’s New X-Men nearly culminates in X-Men versus Magneto, with an evil, warmongering Magneto, a story that ends with his death at the hands of Wolverine. This was decried as antisemitic by other professionals and many in the audience (some of whom have retracted and apologized). It is sometimes still spoken of today as a radical or dramatic departure.

As discussed in What Came Before, the X-Men story that immediately precedes New X-Men, Eve of Destruction, features the apparent death of an evil, warmongering Magneto at the hands of Wolverine.

New X-Men also killed Magneto in its second issue.

At that point, the beginning of New X-Men, Magneto had been a speech giving, kidnapping, genocide-blase mass murderer in action, or comatose and worshipped by genocidal mass murderers, since 1991, making his very partial efforts at not being a genocidal mass murderer last at best half a decade, approximately 1986 to 1991.

Through style and technique, the writer and artists of New X-Men were able to kill Magneto twice, make it feel shocking twice, feel like a huge risk or a step too far twice, the first time only two issues after someone else did it.

If there is a real revolution in New X-Men, it is the storytelling techniques being applied specifically to X-Men stories.

Claremontian has become a watchword for overly-explanatory dialogue or prose. “My name is X and I come from X and my power is X in the X, [cute generic address].”

Chris Claremont casts an appropriate but dangerous shadow over all X-Men properties, having really, along with his classic editors (and two of the most significant writers of mutants at Marvel, in their own rights), Louise Simonson and Anne Nocenti, give shape to the franchise.

Claremont’s techniques of poetic repetition, key phrases, and duopecific narration of the physical events seen in the panels were an immeasurable boon throughout the late 1970s and the 1980s. These storytelling techniques, as well as the Romantic vignettes strung like pearls of 1990s X-authors, the intensive sexual undercurrents of John Byrne and the Cockrums (Dave and Paty), helped cover for sometimes terrible reproduction, help obfuscate a rigid ratings board, while leaving new readers plenty of hand and foot holds that more familiar readers could skip over.

Problem was, by the 21st Century, everyone had their own idea of how much you could skip over. The techniques had become only detriment in a world where the penciler could clarify themselves online, reprinting and collections were far more common, and the general audience was simply more sophisticated.

In e is for extinction, the first arc of New X-Men, techniques that would be common competent examples in other 2001 mediums felt risky and possibly overpowering in an X-Men comic.

Penciler, Frank Quitely, with his carefully framed, texture-heavy art, was unencumbered by duospecific text. He brought a range of body types, facial expressions, and, most important, a range of tone.

Frank Quitely, Grant Morrison, Hi Fi

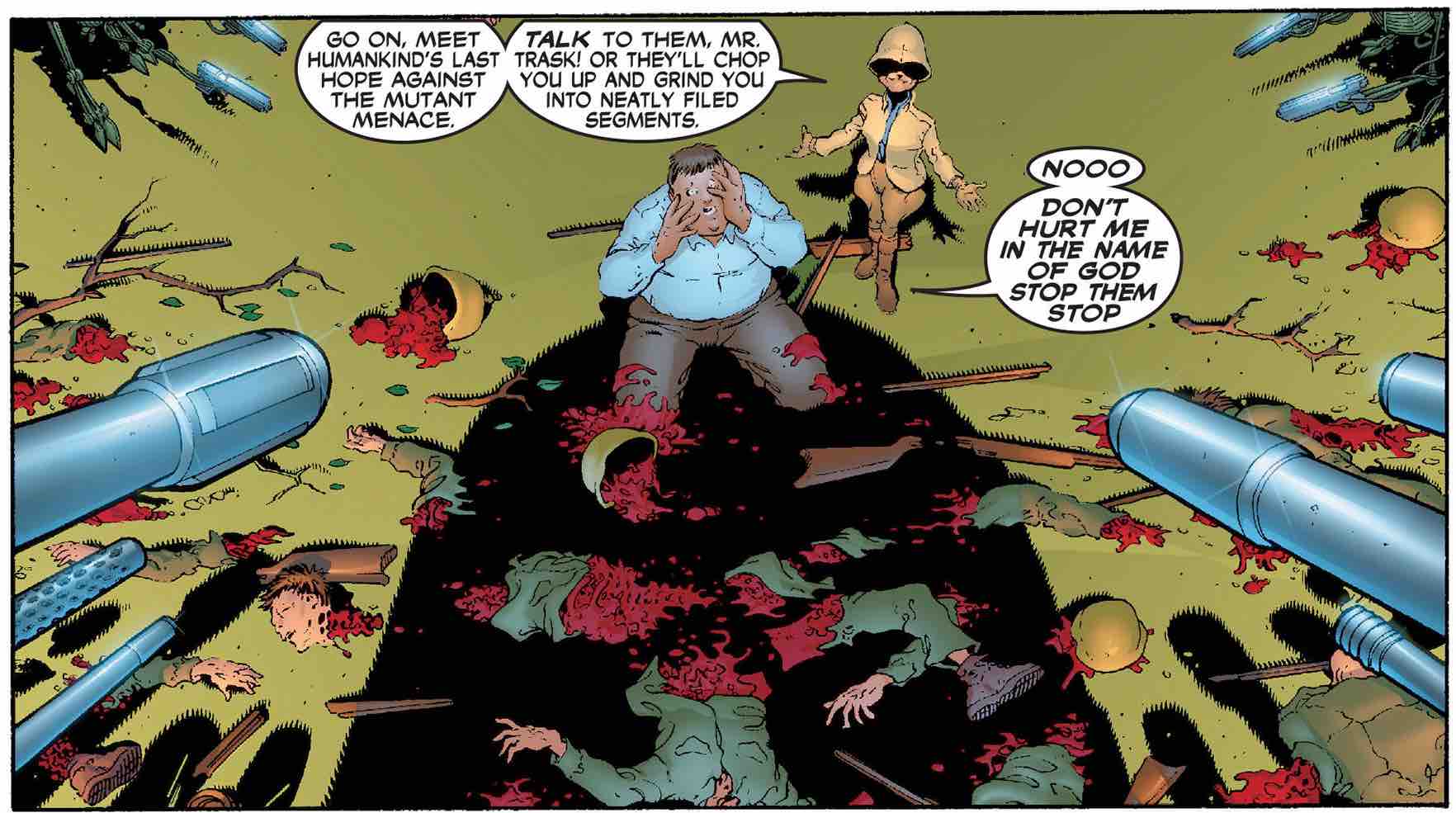

Brian and Kristy Miller’s Hi Fi rendered blood, in the very earliest pages, bright red, when we had been so used to seeing it colored black or faded it out. They brought a level of shading and an ability to make visuals pop that at the time seemed itself almost science fictional.

e is for extinction is an early example of Grant Morrison showing first, explaining a little while later. For example, on the very first page of New X-Men, two men beat up a giant robot in Australia, while a third lies confused beneath a giant robot hand. Only one of these people is named; Wolverine.

We do not return to these characters, in scene, for eight pages, however, two of those pages are a title sequence in which we learn one of the other men’s name (Cyclops) and that both men have two other names (Logan and Scott Summers).

We know that they are in Australia, because the Sydney Opera house is in the background. It needs no text declaration. It does, though, receive a confirmation by dialogue, in a scene following, involving other characters.

The nature and name of the giant robot, and the nature and name of the man lying underneath the robot’s severed hand, come in due time, in the same chapter/issue.

Simply put, information is no longer front-loaded. We no longer get everything we need to know about someone for the entire story from the first panel they appear in.

This was contrary to received wisdom at the time. If you look at storylines from Marvel, including The Crossing, Onslaught, Heroes Return, even when a story poses itself as a mystery, the answers to the mystery are often revealed in early issues or in specialty shop one-shot comics.

An early example, at Marvel, of writing for the trade, New X-Men rewards rereads and it makes them easy. At a time many were finding thick collections of 60s to 90s X-Men related comics sometimes difficult to read through without glazing over some, New X-Men did everything short and sweet.

One of the reasons so much of New X-Men is intuited as new, maybe a distancing effect of this show then tell technique.

Another, that the authors gave the visuals, including hairstyles and clothing, a makeover from outside the traditional drawing wells of the X-Men. EVA and Fantomex reference Diabolik. EVA shares the spelling of her name with the oft-sampled Jean-Jacques Perrey song from 1970, which he occasionally performed dressed as Diabolik-inspiration, Fantomas.

Xorn evokes composer and theorist, John Zorn, and artist, Anders Zorn, and the John Paul Leon/Bill Sienkiewicz artwork in the Xorn-narrated issue, of living and dying, evokes the angles and high contrast of Anders Zorn, as well as his humanist naturalism so well, if it was unplanned it is uncanny. In of living and dying, when Xorn lies across a horse in danger, is it a Friedrich Nietzsche shoutout? Does it matter?

Charles Xavier will, later in the run, tell Quentin Quire that Magneto was “kind to animals,” a revelation that is both characterizing for all three of these characters, but also feels new, feels refreshingly new. But, maybe it’s just a reference.

Ernst is explicitly named for painter, Max Ernst, and careful readers will suss out that she is Cassandra Nova, and Cassandra is her. Marvel and later Marvel authors either missed this, misinterpreted it, or consciously chose to ignore it, to preserve them as separate characters that would see no great future use, for the most part.

Reverberations of intimation. Not stepping stones or necessary circuit breakers.

Grant Morrison, Frank Quitely, Tim Townsend

One of the first mutants we meet, who are original to New X-Men, Negasonic Teenage Warhead is dead before she appears, and has since been adapted into the Deadpool movies. NTW felt fresh, with her second half of the 90s goth style and her name which has the poetry of a Fabian Nicieza character, and to go along with those 90s touchstones, NTW named herself after a 1995 Monster Magnet song about, not doom, not gloom, but confronting and combating early 1990s grunge music maudlin.

Negasonic Teenage Warhead (the song) is about seeing “every supersonic jerkoff who plugs into the game,” and, “every subatomic genius who just invented pain,” on television, hearing them on the radio, and saying, “I will deny you.”

Beak, an anxious chicken-like student, is given a Revolting Cocks t-shirt and Sid Vicious’ padlock necklace, decades past their traditional teenage fandom.

The gang formed by teen upstart and hip bigot, Quentin Quire, dress in the style of a human artist’s scaremongering interpretation of a mutant take over, from the year Quire was born.

Pitching the gang to its members, Quentin leans on, “The next generation… like on tv,” a reference to either the Star Trek program canceled nearly a decade earlier, or the Degrassi spin-off, debuting in 2001, depending note on his frame of reference, but ours.

Quire calls his gang, the New X-Men.

Everything inescapably has to have connections to past things, but there is a difference in being supported by the past and being dependent on knowledge of the past.

The new costumes that the X-Men wear, black leather and caution tape yellow, are visually tethered do the early X-Men movies, specifically the first, a movie that made that choice because it was the safest choice. The first X-Men movie made a decision to distance themselves from visual superhero tropes to bank on a larger audience, and in hopes that audience would take them more seriously.

When, in e for extinction, Beast says he never understood why Charles Xavier have them dressed like superheroes if they were first responders, rescue workers, it is not because Beast is holding superheroes in disdain. Beast had been a member of multiple superhero teams at that point – the Avengers, the Champions, the Defenders – but he is right that traditionally, the X-Men do not go look for crime to stop, their primary initiatives are the rescue and caretaking of other mutants, fostering relations between mutants and other cultures, disaster relief.

It’s about looking the part.

Part of being new, is that everything old is new again, but just the style of it, not the context. The context cannot be the old context.

The New X-Men costumes do not, really, look all that different from the original X-Men costumes, adding, mostly, seams and tread, and doing away with masks. Black and yellow. Standardized. Dark limbs, yellow around the torso.

Quitely/Morrison 2001 & Kirby/Lee 1963

Color is both forward and nostalgic in New X-Men, with a note about Professor Xavier hand painting water colors of their early supervillains to educate the X-Men in identifying their costumes as if they were heraldic coats of arms. One of the tips that Xorn is a disguised Magneto is a purely impressional use of Magneto’s traditional color scheme, a symbolic crest only for the readers.

In the final arc, Here Comes Tomorrow – named after a 1966 Monkee’s song written by Neil Diamond, Look Out (Here Comes Tomorrow) – we are shown a radical, dramatically different future, human populations collapsed to only a single, desperate, superhero city, the rest of the Earth wastelands of abused climate, nations of mutants and of have intelligent termites. Ironically, this is not some deep ten million years later future, but only a few generations from our modern day.

The far future of Here Comes Tomorrow is drawn by a quintessential late 80s X-Men artist, Marc Silvestri, doing a hyper-competent take on his earlier run, and colored with that earlier run, and a famous cover of a crucified Wolverine, specifically in mind. The entire future is suffused with purple and green.

Everything in his future feels strange and new, but it is the same hypocrisies, the same political and familiar squabbles. Events and even personal names mirror biblical stories and historical events. Wolverine compare is it to the fall of Rome. Beast believes he is a kind of beast of the Apocalypse.

Many of the background characters are remixed allusions to preexisting characters, while types have emerged, including a proliferation of angel-like and demonic-seeming mutants and a new lifeform that seems to be Cassandra Nova’s predecessor yet in her future.

“I even based the Imperial Guard on members of the Legion of Super-Heroes,” admitted Morrison, “I was thinking of everything that have been done before and trying to do an updated version of it.”

When the Shi’ar Imperial Guard, created in 1977 by Dave Cockrum and Chris Claremont for Uncanny X-Men, make their New X-Men debut, they appear strange and new, yet real differences from previous portrayals are only mildly different translation of their title, now rendered as the Imperial Superguardians, some cosmetic alterations, and casual portrayal of their alien abilities as explicitly alien.

The secret lab in England called, The World, call to mind the wave of British-first comics, Marvel UK, and their early 90s habit of pairing new, mostly lab-grown superheroes with members of the X-Men.

As Grant Morrison put it, “If you are playing The Blues, you have to play a C chord. If you are playing X-Men, you have to play certain elements.”

of living and dying may, in its title, have a reference to Sogyal Rinpoche’s The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying. Or, perhaps not.

Everything is a reference, everything from an influence, runs the risk of becoming confusing and septic, but within New X-Men, knowing what the references are can be entertaining, but it is never necessary.

All necessary information at any given moment is on the pages. Not another comic published the same month. Not in twenty year old comics identified in the footnotes. Not in special spell everything out oneshots or guidebooks.

In playing X-Men, Morrison made certain they played the chord in their comic.