Patricia Highsmash

Examining New X-Men Pt 6

by Travis Hedge Coke

From 2001 to 2004 Grant Morrison (The Invisibles, Batman and Robin) and team of pencilers, inkers, letterers, editors and colorists, including Phil Jimenez, Mike Marts, and Frank Quitely made a comic called New X-Men.

Revitalizing the X-Men as a politically savvy, fashion forward superhero soap opera, New X-Men was published by Marvel Comics as the flagship of a line wide revival.

Part 6

21st Century Global

New X-Men launched with a Scottish writer and Scottish penciler, and throughout the run had contributions from American, Canadian, Croatian-born, Filipino, and Malaysian talent.

9/11 happened between the second and third issue of New X-Men, (issues #114 & 115), and came to greatly dominate the comic throughout the run.

Grant Morrison, Frank Quitely, Hi Fi

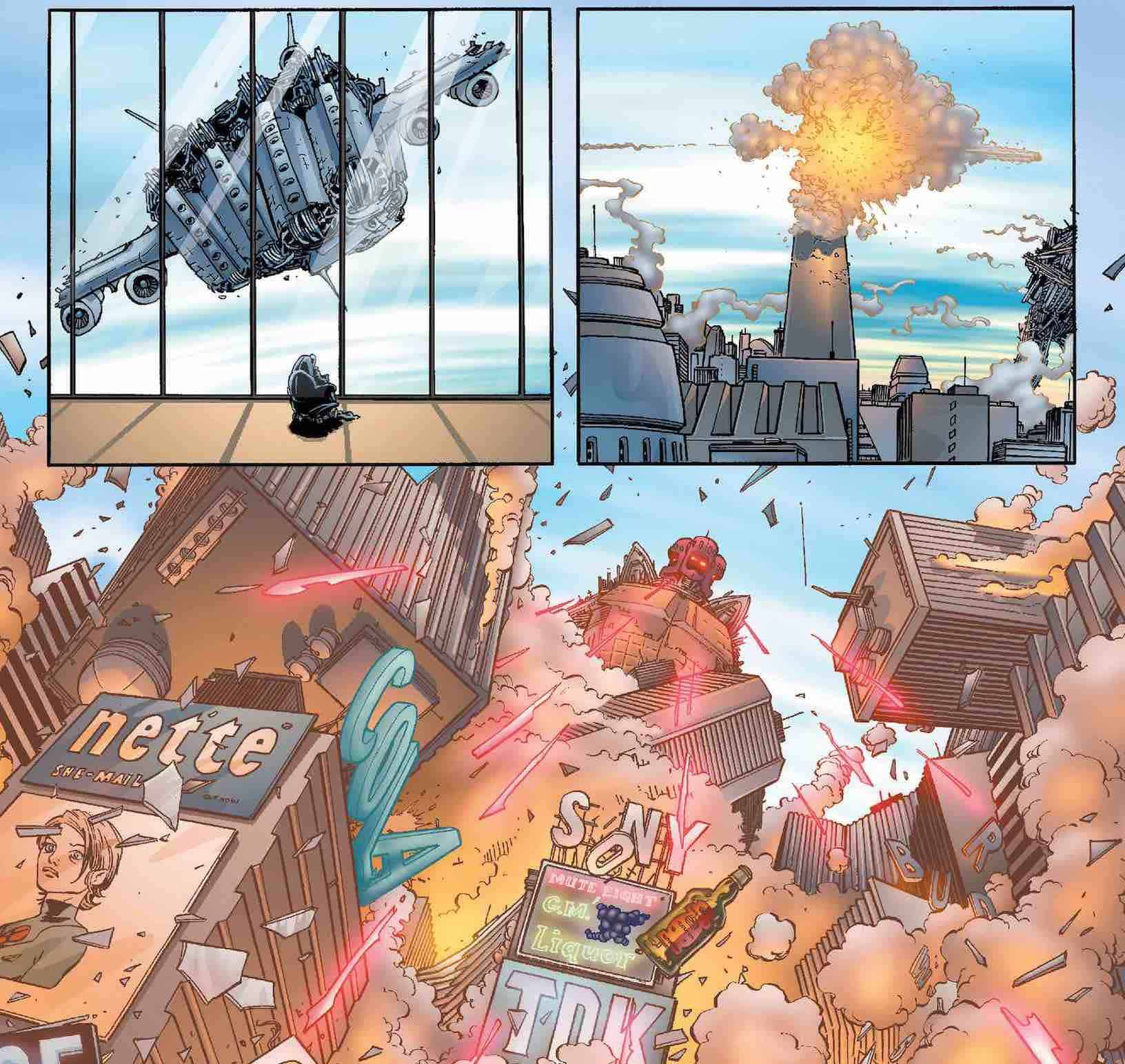

Like The Dark Knight Strikes Again (Frank Miller, Lynn Varley), New X-Men‘s first arc, e is for extinction, featured urban decimation by an airborne threat, before anyone who worked on those comics had any inkling of what would occur on September 11th, 2001. And, like DKSA, New X-Men embraced is true life event, how it affected people, media, their own audience, an interplay between that audience and the comics.

Unlike DKSA, which was redirected by 9/11 into the heroic beating of the American government and American billionaires for collaborating with our assaulters, or the myriad tribute books of single panel illustrations or relief workers turned vigilantes, New X-Men stayed a path away from militarism or highlighting the empathies of supervillains.

Comics publishers produced Artists Respond, A Moment of Silence (with Rudy Giuliani), Heroes, and The World’s Finest Artists Tell Stories to Remember, which directly dealt with the real life events, though often through the intermediary of the trademark characters each publisher owns.

While Croatian-born New X-Men artist, Igor Kordey, would contribute to a direct tribute book with his piece (now held in the Library of Congress collection), Pennsylvania Flight, showing hijackers and innocent passengers onboard on of the airplanes weaponized in the attacks, other artists presented Spider-Man tired, Captain America sad, villain and dictator, Dr Doom, crying.

The Ultimates, which used an Incredible Hulk attack to proxy, still amped up the jingoism and xenophobia under guise of patriotism and “realism”/”hard choices,” culminating in nigh-parodic anti-Islamic sentiments and “both sides” political centrism that played commercially to the buckling of colonialist pride and an increased sense, in the States, of being at risk.

Marvel very quickly wrapped up The Brotherhood, an isn’t terrorism sexy here is a woman for a prize for being a sexy terrorist comic written by a then-pseudonymous Howard Mackie, that plays like the worst Mark Millar experience you can imagine.

Grant Morrison, Frank Quitely, Hi Fi

United, the Chaos Comics response, featured demonic, hypersexualized bad girls, some of whom had previously participated in the complete massacre of Manhattan, lament and defend in post 9/11 New York.

Frank Miller’s first completely post 9/11 comic was the ethically and psychologically ugliest of his ouvre, also pushing a militarization of the superhero as healthy.

Grant Morrison said, in Arthur Magazine, “I think we have to give them images of rescue and ambition and cosmic potency, rather than images of control and fascist perfection.”

Dr Doom and the Green Goblin aghast at 9/11 is up there with John Byrne’s patriotic Joker or the kind of people who are fine with a murderous, rapist character, but they better not be cruel to a dog.

The standard response in American comics was one of confusion, anger, reaction to being wounded, which is how it became 9/11 and not the ongoing series of wars and conflicts, the Afghanistan Civil Wars, the United States Invasion of Afghanistan, the War on Terror, Operation Enduring Freedom. Abroad was, largely, abroad. Even non-Americans working for American publishers were limited, even self-limited, to Americana and the American response.

And, the American Response was packaged.

Kordey, just previous to New X-Men, had been working on the brilliant Soldier X, a comic following the quintessential soldier into impossible retirement and the nature of war. His own experiences in life and the nature of his personal work, kept him noticeably distanced from the the kind of comics where superheroes gave George W Bush a thumbs up and called the French cowards.

One American artist, would be let go from New X-Men around a third into Grant Morrison’s run, in light of slowness, returning to DC Comics and work for extreme right-wing publications.

Both of the stories dealing with after-effects of terrorist desolation (Ambient Magnetic Fields and Planet X) were drawn by New York-based, gay, Latinx artist/writer, Phil Jimenez, both of those stories concerning the complex figure, Magneto.

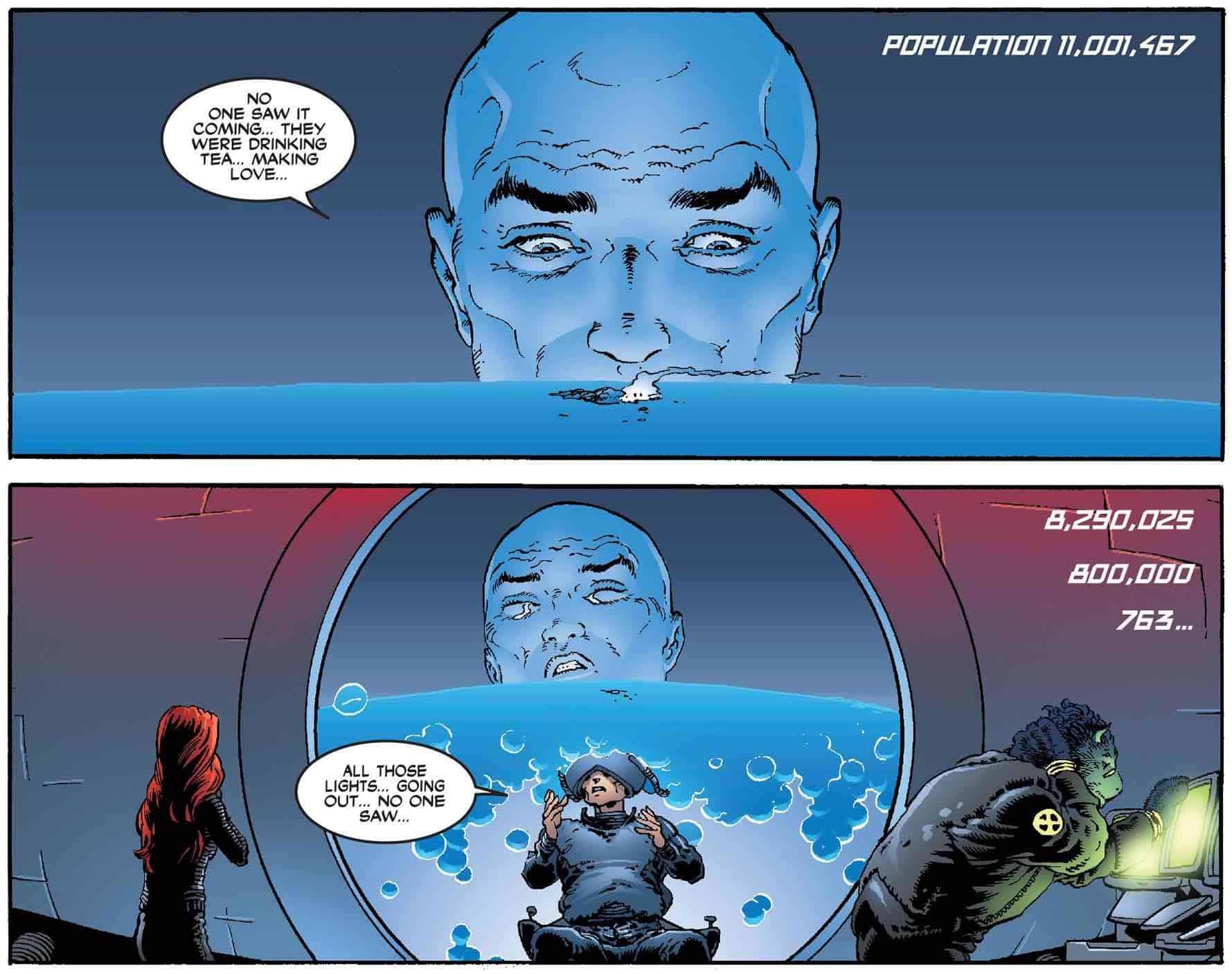

Early in New X-Men we we saw Magneto appear die in a terrorist action against the nation of Genosha. In Ambient Magnetic Fields, the X-Men return to the island where sixteen million people were murdered, to assist in disaster relief, and investigate mysterious hauntings, that are eventually identified as a grieving and confused Polaris, possibly Magneto’s daughter, and an electromagnetic message that Magneto used his powers to record during his apparent death, detailing his message to the future.

“Our voices will be broadcast around the world… Into space. At the speed of light. At the speed of radio. Our voices traveling without end through the depths of time and space. Beyond this life. And far, far… Beyond this death.”

Magneto’s message resonated with a post 9/11 readership. It was a testament to victims, to innocents.

In Planet X, serialized over a year later, it is made clear that Magneto was not innocent or a victim, that as the head of state of Genosha, Magneto conspired to commit genocide, assisting in – and making his escape during – that terrorist attack.

Andy Lanning, Phil Jimenez, Grant Morrison

Magneto’s resounding, somewhat sacharrine message to the world was its own encoded terrorist attack, facilitating his personal destruction of several blocks in the New York neighborhood with the highest concentration of mutants, District X, a general assault on the city, and a threatening shut down of much of the rest of the world.

This arc had been pre-plotted, though naturally things changed along the way, and it may be a testament to how much New X-Men made people pay attention again, that the Planet X story received so much anger.

Paty Cockrum implied Grant Morrison and editor-in-chief Joe Quesada were anti-semites involved in a specifically anti-semitic conspiracy.

A reader made credible death threats to Morrison over the death and life of Jean Grey under their control.

Chris Claremont almost immediately absolved Magneto of culpability (and then very quickly cast doubt on his absolution, because Chris Claremont is a complicated writer).

Magneto has been, largely, not an out-and-out supervillain in the nearly twenty years since New X-Men, although he has continued to do villainous, or at the least on heroic things with little consequence or in-story judgment.

A character who had caused global mass murder in the mid-1990s, who had caused arrest of international politics only a few years before New X-Men, when writer/artist Alan Davis with steering the ship, who had been created in 1963 as a kind of Hitler, was causing waves of distress for smashing up a few city blocks and killing less people than contemporaneous superhero titles like The Ultimates, The Mighty Avengers, or The Authority.

People – let’s be clear, American people – were far angrier at him damaging New York property and murdering New York residents, then they were with him being complicit in the murder of 16 million foreign nationals. But, for many around the world, this Magneto story, this level of assault, was thirty years too late, even though it followed on and echoed so many other assaults filling those thirty years.

A Holocaust survivor, Magneto’s relationship to persecution is complicated by that aspect not being introduced to his character until nearly twenty years of stories have been published. These included stories where Magneto and his armies were visually modeled after Hitler and the Nazi military, stories in which Magneto participated in the conquest of innocent nations, the persecution of Indigenous peoples, eugenics experiments, slavery, supremacist agendas, and the theft of nuclear weapons.

In terms of Magneto’s fictional life, he was a Holocaust survivor first, but in terms of publication, he was a war criminal, an enslaver, and a conqueror first.

The genius, both of Neal Adams’ visualization of Magneto as a rounded and specific person, and Chris Claremont’s development of Magneto’s complex and difficult life, is that for many decades, we have collectively, as an audience, wished Magneto would stop being the badguy.

Even though, it was always in context a horrific and tragic event, and the villain was always treated as a horrific, and tragic villain, the treatment of Magneto in New X-Men may have been too close to home, especially that it was someone who, in earlier issues, had been turned into a poster and t-shirt icon inspiring jaded teens and disaffected would-be revolutionaries.

A fictional character cannot be judged by their actions the same way that a real world person must be, because a character’s actions are not as resonant as their makeup, as all the points they touch, everything they make shine or sound.

The X-Men movies, then so fresh, had presented a Magneto played by Ian McKellen so charmingly, that in the first movie, X-Men, Magneto kidnaps a teenage girl with plans to risk her life for his political goals, and in X-Men 2, he and a fellow terrorists make fun of the lasting changes their experiments on her made to her body, and people laughed, and laughed, and cheered.

Oooh, he’s so catty and sharp! Rrawr!

It is an amazing performance, absolutely bolstering both films, but with distance the audience reaction is disturbing, and mirrors the prolonged nostalgic clinging many comics fans experienced for a Magneto from a brief in the 1980s. A time period, during which Magneto was still much a terrible person who made no efforts at restitution, minimal efforts at rehabilitation, and kept doing bad things.

Morrison’s career has been marked, more than almost any major superhero comics talent of their generation, by their refusal to encourage a lack of judgement against supervillains. Morrison’s Lex Luthor is a bad, criminal person. Their Talia al Ghul, a terrorist and capitalist nightmare.

If there is a lack of narrative condemnation, in one of Morrison’s superhero stories, it is almost always explicitly the point, and yet even in those, murder and conquest, et cetera, are not rewarded with get-out-of-jail-free cards because someone is charming or because the character can’t be written out of the series.

Reflecting in 2021 on the mythologizing and making gentler, the lionizing and excusing for George W Bush, for Chris Kyle, the recent return of Republicans to calling for the empathy of Ronald Reagan, it is easy to imagine why, even with a substantial history of conquest, mass murder, kidnapping, brainwashing, assault, attacks on foreign nations, and holding the world hostage, a substantial portion of the traditional superhero comics audience wanted a Magneto who would not be held accountable and maybe would just stop doing bad things so loudly.

Magneto, in Planet X, ragingly asks a teenage boy who just called him Hitler, if he looks like a frustrated artist. But, maybe if Magneto had taken up painting as a form of therapy, we’d all be that little bit happier.

It would be easier to forget the abuses, in the same fashion that it has become popular to insist that Malcolm X was the inspiration for Magneto, instead of acknowledging the influence of Hitler. Malcolm, of the two, being the more famous for his invasion of foreign countries, enslavement of indigenous peoples, hijacking of nuclear weapons, and marching his armies and colored Nazi uniforms.

That Magneto could stop being a terrible person at any time is not even an undercurrent in Planet X. It might be the real crisis if he wasn’t murdering people, which takes priority.

Having disguised himself as Xorn for about thirty issues, Magneto has come to understand everyone likes Xorn better. He might like Xorn better, because when he was Xorn, even if he was being a jerk and making fun of people, they genuinely liked him. And he wasn’t always putting on an act.

In 1991, Chris Claremont and Jim Lee, established that Magneto was chemically imbalanced, a health issue but Dr Moira MacTaggert had tried and failed to cure. This has forever since gone unacknowledged, leaving Magneto all serious ways responsible for both his bigoted beliefs and his violent, corrupt, and sadistic actions.

9/11 affected the way the average American responded, and it was a fresh enough wound that they were incapable of processing just how it affected them. This conflated within a person, in combination with fear of stepping too out of line and being seen as uncaring or unpatriotic.

The readiness the audience to absolve Magneto, and the readiness in more recent years, to absolve Charles Xavier of crimes before and after New X-Men, does well as ignoring his possible psychic culpability in the Cassandra Nova mass murderers, is the readiness to nicen the myth-figure of George W Bush. It is the absurdity that at the time of New X-Men led to many people to declare Rudy Giuliani, America’s Mayor.

The tragedy and hurt draws attention back to New York like a gravity well, back to those attacks, but what is at play is a fictional representation of real world global history and present.

X-Corp, the globalization of the X-Men, have offices in Mumbai and Paris. Rather than all these non-American characters being moved to America, Americans become like any other, expatriates and emigrants to places around the world.

Not, are they all superheroes. Some are. Some proudly. Others are relief workers, office staff, teachers, scholars, legal aid and doctors.

In most superhero comics, including most X-related, travel is something you do in a transitional panel or for a rare one off story. In New X-Men, travel is a part of life, and for international aid workers like the X-Men, of daily life.

Charles Xavier and Jean Grey are constantly on outreach and administration trips.

Wolverine might pop over to anywhere in the world on his wanders, including taking Cyclops to England on a fact-finding and de-stressing exercise.

The X-Men have their special jet planes and helicopters, but sometimes they fly commercial.

In New X-Men #133, Xavier and Grey are aboard the hijacked Air India flight 1212, and Xavier uses his psychic powers to “explain some of the destructive inconsistencies,” in the plans of one of the hijackers, promising he will never again, “use violence in the service of abstract ideas.”

Xavier also uses his super powers to ensure that the hijackers, “will not be brutalized in [police] custody.”

While Xavier does not likely think of himself as an American interventionalist, he is here dominating the paths and wills of foreign governments and foreign rebellions. The irony of “violence in the service of abstract ideas,” does not even seem to register to him as he goes to check on the branch office of his X-Men.

Issue #133 is the only New X-Men issue without a title, which might be deliberate, may be an issue of deadlines, but may also be merely a lapse in paste up, similar to missing numerals in the third issue of e is for extinction.

#133 introduces Dust, a character intended to have a greater presence, but who ends up barely a blip, and unfortunately a blip with more stand-out unlikelihoods than characterization.

Grant Morrison, Phil Jimenez, Andy Lanning

A young woman initially seen having killed men who were trying to traffick her in Afghanistan, Dust is so traumatized she can only speak one word, the word for dust in Arabic, a language only spoken by about 1% of people in Afghanistan. She has the mutant ability to become a cloud of dust she can manipulate, in which form her thoughts are also protected from telepaths, but initially, Morrison intended her to be an update of the DC character, the Human Bomb, something they realized preemptively as bad.

Anti-Muslim sentiments were so high in the United States, that Morrison consciously reduced her presence, but her two significant New X-Men appearances play off assumptions of guilt while consistently reemphasizing her innocence.

#133, following Ambient Magnetic Fields, has a cover paralleling Dust with Magneto. When Magneto launches his terrorist efforts from within the X-Men, one of his final moves before going public is to blame Dust and a religious antagonism/cultural conservatism/not-like-us sentiment he ascribes to her, so that she is the object of characters’ and readers’ suspicion and ire.

Frank Quitely

The X-Men become a metaphor for American invasion, for American international assistance. As it was received wisdom in many circles that the Al Qaeda attacks on the United States were a result of America’s failure to follow through after their military assistance and encroachments in the 1980s, the X-Men are willing to arm foreign nationals, to establish outposts, but fall short on the long run. They get caught up fighting the same wars in perpetuity.

It is no mistake that in the same comic as Dust is introduced, Xavier is mind-controlling away foreign politics, and Xavier’s marriage to an alien empress is dissolved as they swear off Earth and Earth politics, noting that Earth-people are infested with combative and jealous thoughts, which readers and characters misunderstood, at that time, to be indicative of human or mutant threat.

We read, as they heard, “toxic levels of aggression,” and we thought it was us. That we are our aggression. And, like the X-Men, apprized of this knowledge, do we do nothing, ourselves, so cure or correct those levels?