For this last day of Pride Month 2022, we thought we’d re-present Lillian Hochwender’s beautiful, thought-provoking three-part analysis on Loki’s genderfluidity. Enjoy!

Content Warning: While I’m using the word “queer” extensively throughout this commentary as an umbrella term relating to both people with marginalized genders and sexual orientations, it’s not a word all LGBT+ people are comfortable using due to its history as a slur.

This is Part 2 of a short series exploring Loki’s genderfluidity in Marvel. Part 1 contains definitions of genderfluidity, background on Loki, and an analysis of the affirming story of Loki: Agent of Asgard. Part 2 analyzes how comics after AoA have depicted Loki in regard to genderfluidity and offers an introduction to queer-coding and comics censorship. However, for readers without an interest in comics, this article can be read on its own.

In the 1995 documentary The Celluloid Closet, director Harvey Fierstein explains how it feels to consume media as a queer person: “Readings in school were heterosexual. Every movie I saw was heterosexual. And I had to do this translation. I had to translate it to my life, rather than seeing my life.” As we watched Loki in 2021, many queer people did what we’d done with countless television shows and films before Loki: we found our stories indirectly by reading allegorically — by translating. What I hope to offer in this commentary is not just my own “translation,” but a look at other translations, an exploration what it means to translate Loki as a queer person, and why translation isn’t enough.

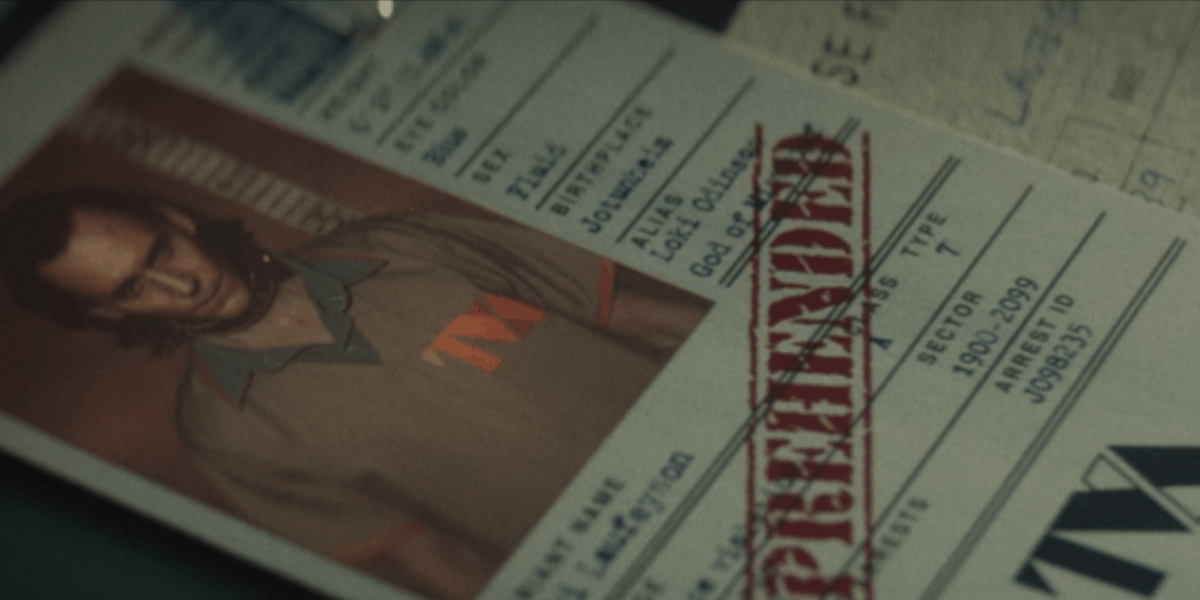

Loki’s TVA dossier, as seen in Loki Episode 1

48 hours before the show’s first episode aired, Marvel dropped a trailer depicting Loki’s Time Variance Authority (TVA) dossier. Among details like his eye color and height were the words “Sex: Fluid.” Although Loki has long been genderfluid in both comics and Norse myth, Marvel Studios’ hesitancy to portray queer characters made this onscreen reference to his genderfluidity feel like a promise of real representation. When interviewed by Inverse, Loki head writer Michael Waldron stated that “everyone will have to watch and see,” while Loki’s actor Tom Hiddleston emphasized the historical precedent for Loki’s genderfluidity and “breadth and range of identity.” He went on to state that the entire team had felt responsible: “I know how many people identify with Loki in particular and are eager for that representation, especially with this character.” Yet, in the event, Marvel sidestepped almost all representation of Loki as genderfluid. Loki remarkably came out as bisexual (due to the hard work of Loki’s bisexual director Kate Herron), but his gender was only ever addressed by the TVA dossier when it received a few seconds of screen time in episode 1.

The act of promising or teasing queer representation without delivering on it for the purpose of capitalizing on a queer audience without alienating mainstream audiences is referred to as “queerbaiting.” It’s something Marvel Studios and Disney more broadly has become infamous for and it often involves “watch/wait and see” statements like Waldron’s. “Wait and see” is useful: it’s coy and encouraging but not specific or explicitly affirmative. For example, when Avengers: Endgame disappointed viewers with “Marvel’s first openly gay character” (a character called “Grieving Man” who has a single line), producer-directors Joe & Anthony Russo assured audiences of an established secretly gay character whose identity will one day be revealed (“We’re gonna find out!” said Joe). When fans saw homoerotic subtext in this year’s The Falcon + The Winter Soldier, an interviewer asked lead writer Malcolm Spellman if the show would portray Bucky Barnes as bisexual. Spellman encouraged viewers to “just keep watching.” The Russos themselves aren’t making any more Marvel films and Bucky didn’t come out of the closet, but the “wait and see” did its work: it made people watch. The same can be said for Loki. Is he now canonically bi? Certainly. Genderfluid? Not so much.

“It’s Not About You:” Erasing Genderfluidity

Throughout comics like Al Ewing’s Loki: Agent of Asgard and Thor and Loki: The Tenth Realm, Loki frequently shapeshifts between different gender presentations. In this regard, the comics offered the Disney+ series a framework for depicting Loki’s genderfluidity. Instead, the show created Sylvie: a female Loki variant from another timeline. Why does this matter? Because the show’s creators had taken a genderfluid character and broken that character in two. The show offered a male Loki and a female Loki, but never a Loki who is both, or whose gender goes beyond the gender binary. In fact, none of the show’s many Lokis change gender or gender expression. The closest audiences get to gender shapeshifting is via stunt doubles: male and female stunt doubles were regularly swapped out throughout Loki’s first two episodes to keep the audience uncertain of Sylvie’s gender until her full reveal as a woman at end end of episode 2. Real-world genderfluid people (me included) are incapable of shapeshifting, but do have changing gender identities — and may change gender expression to reflect that. The show makes no attempt to depict that either.

When dialogue addresses Loki’s gender, it’s never to address Loki’s genderfluidity. Sometimes, it actively undermines it. A key example comes from episode 5: “Journey Into Mystery.” As Loki searches for Sylvie, he has the following interaction with one of his other selves:

Loki: Have any of you met a woman variant of us?

Classic Loki: Sounds terrifying.

Loki: Oh, she is. But that’s kind of what’s great about her. She’s different.

Here, the show’s writers didn’t simply undermine Loki’s genderfluidity: they erased it. All of the Lokis in this scene — main protagonist Loki, an old man, child, a Black man, and an alligator — are male. The same can be said for the “gang” of Lokis they fight later on. Rather than establish female or feminine gender as something some or all of them had experienced, the dialogue made it clear that Sylvie’s gender made her different from any other Loki. And more unbelievable than an alligator.

Alligator Loki

When The Direct asked Herron about the scene, she replied: “maybe Classic, Boastful, and Kid [Loki] haven’t quite got there yet in their timelines. Or maybe they’re not genderfluid, those particular Lokis. I would say it’s open to interpretation.” As justification for a lack of representation, this answer rings false. If being bi is an essential part of who Loki is (which the show implies), it’s only logical that genderfluidity would be too. If one or two Lokis haven’t learned to accept that part of themselves yet, it’s only nuanced representation if the narrative offers them room to grow: it doesn’t. Rather than being offered substantive representation (or even a confirmation of genderfluidity from one of the other Lokis), queer people are given only the possibility of “interpretation.” At the end of the second episode, Sylvie had declared to Loki that “this isn’t about you,” and, watching episode 5 as a genderfluid person, that felt more true than ever.

Queer Eye for the Villainous Guy: Queer-coding Loki

Queerbaiting exists within a longer history of media censorship that has erased queer people and narratives from film. In 1930, white Irish Catholics formed a large contingent of American moviegoers and pressured the film industry to create the Motion Picture Production Code, a.k.a. The Hays Code. The Hays Code was a collection of several rules ostensibly meant to “maintain social and community values in pictures.” The Code forbade, among other things: use of liquor, adultery, miscegenation (interracial relationships), and “sex perversion.” “Sex perversion” was a catch-all for both portrayals of homosexual relationships and transgender people. In 1954, the newly formed Comics Code Authority adopted this prohibition word for word.

To portray queer experience, writers and directors found ways to circumvent the Code. Gore Vidal, the bisexual screenwriter of Ben-Hur, explained, “Well, you got very good at projecting subtext without saying a word about what you were doing.” This “projection of subtext,” as Vidal calls it, can also be called queer-coding. For decades, queer audiences have had to “decode” or translate this queer-coding to see themselves. The Hays Code was eventually abandoned in 1965; queer-coding remains.

Queer-coding, unlike queerbaiting, isn’t exclusively negative. Historically, it often allowed queer storytellers like Vidal to depict their lives on screen. At the same time, queer-coding was often (and continues to be) attached to villains. Queer-coded characters generally represent queer stereotypes and transgress gender norms (women are too traditionally masculine or men too traditionally feminine) and are punished by the narrative: cast as villains, killed off, or both. A multitude of Disney animated villains are queer-coded, including Jafar, Maleficent, Scar, and — most notoriously — Ursula, who was inspired by legendary drag queen Divine. Like many queer-coded male villains, Loki: has a slim build, is driven by emotion, has a very close relationship with his mother, enjoys the fine arts, and loves fashion. Even if film viewers had never read Marvel comics or Norse myth, the MCU films used the shorthand of queer-coding to demonstrate Loki’s villainy.

Loki, in the show’s first episode, sits down in the Time Theater and watches a film of himself — the villain. Even though he’s clear it’s not who he wants to be. Most queer people haven’t committed war crimes, but I promise most of us do know how it feels to sit down in a theatre and see ourselves only in the villains. To want a different story.

“A Bit of Both:” Explicit Representation

While Loki’s first season didn’t portray Loki’s genderfluidity, it did do something unexpected: brought him out of the closet as bisexual (something equally canonical to the comics). The scene happened in Loki’s third episode, “Lamentis,” which aired on the last day of Pride Month. As they share a quiet moment in the club car of a train hurtling through an apocalyptic landscape, Sylvie and Loki compare their life trajectories, discussing their parents, love-lives, and definitions of love. During this discussion, having confessed her own ongoing affair with a postman, Sylvie asks Loki: “How about you? You’re a prince. Must’ve been would-be-princesses or perhaps… another prince.” Loki smiles coyly and replies “A bit of both. I suspect the same as you.” With this line, Loki became the MCU’s first canonically non-heterosexual main character. Though the moment is still brief enough to be edited out (Disney censored queer content with both Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker in Singapore and Avengers: Endgame in Russia), this scene makes Loki’s bisexuality irrefutable.

Cinematographically, the episode seems to reinforce Loki’s bisexuality through a purported cinematic trope called bi (bisexual) lighting: the lighting of a bisexual (at least implied) character with pink, purple, and blue: the colors of the bisexual flag. While the bi lighting seems most obvious in this specific and intimate conversation, the entire episode is bathed in it. “Lamentis” seems like it may be an instance of intentional bi lighting, with Sylvie’s actress Sophia Di Martino mentioning the lighting on twitter and telling Variety that she thought Kate Herron was doing it intentionally. In addition to bi lighting, the episode began with a song by openly lesbian singer Hayley Kiyoko. However, while the episode feels queer, this feeling is still predominately reached via translation.

A selection of bi lighting examples from “Lamentis” and its promotional stills

When the episode aired, reactions were split. A headline in The Independent stated “Loki being bisexual isn’t the big representational win some are making it out to be,” and attached was a column disappointed in how little screentime Loki’s bisexuality received and how viewers like the columnist are tired of being placated with “crumbs.” Meanwhile, PinkNews celebrated with the headline: “Loki sends Marvel fans into orbit by confirming the trickster god is canonically bisexual.” While Captain Marvel’s producer asserted that her film was forced to choose between Carol Danvers’ journey of self-discovery and her queerness (nonetheless depicting a queer-coded relationship between Carol and her best friend Maria Rambeau), Loki proved it was possible for those two things — queerness and self-discovery — to coexist.

Still, it’s crucial to note this scene’s context in broader Marvel canon. Loki’s coming out came after not just the let-down of Endgame’s “first openly gay character” and a history of queerbaiting, but after multiple instances of Marvel self-censoring and cutting queer scenes for named female characters in both Thor: Ragnarok and Black Panther. While the Hays Code may have been phased out decades ago, the modern MPAA ratings system often still treats queer relationships as more “mature” and rates them as such, and film studios like Marvel continue to self-censor, most likely to preserve the marketability of their movies.

In some ways, Loki’s representation of bisexuality is still “safe”: it’s on the small screen on a streaming platform, and Loki is never portrayed as romantically involved with men. Sylvie, also implied as bi, is similarly not shown romantically involved with women. Rather, the show couples Loki and Sylvie with each other. (I will note that calling their relationship heterosexual erases their bisexuality.) Whether or not Loki would believably fall for another version of himself (he would) concerns me less than a comment made by Mobius, Loki’s new and only friend, who, when finding out Loki is fundamentally in love with himself, tells him it’s a “sick, twisted romantic relationship.” Loki and Sylvie’s relationship is far from normal, but Mobius’ comment couches it in the language of deviance, which is deeply harmful in relation to a character who came out as bisexual only one episode before. The narrative often treats Mobius as Loki’s (flawed) moral compass, but also makes him a “point of view” character for the audience. It’s Mobius who doesn’t see Loki as a villain and someone capable of good, which in turn helps the audience see him the same way. When he says Loki’s relationship with Sylvie is sick and twisted — even if he befriends Sylvie later — the audience is pushed to take his side.

Loki’s deaths in Thor (2011), Thor: The Dark World (2013), and Avengers: Infinity War (2018)

“Mere Survival:” Loki as Queer Allegory

Much like Loki in the Time Theater, queer people walk into the theatre and watch ourselves die. Loki was dead before he was even out of the closet. One way Hollywood has classically punished both queer-coded and openly queer characters is the same way homophobic and transphobic societies punish queer people: death. The trope of killing off queer characters to help cis/straight protagonists grow has been dubbed “Bury Your Gays.” “Bury Your Gays” is most frequently reserved for women, with the death of Lexa on The 100 spotlighting the trope in 2016. Even before Loki came out in the MCU, he’d been killed off three separate times to further Thor’s character development (Thor, Thor: The Dark World, and Avengers: Infinity War). Like other queer characters, as Mobius tells Loki in episode 1: Loki exists “all so that others can be the best versions of themselves.”

However, unlike queer characters who came before him (thanks to his popularity with audiences), Loki never stays dead. And, as remarked by YouTuber Jessie Gender, Loki’s act of overcoming “Bury Your Gays” “speak[s] to that real-life LGBTQ resilience in the face of stigma and pain.” Enter queer survivorship allegory.

In the show’s second episode, Hunter B-15 tells Loki: “I don’t want anyone out there to forget what you are…. A cosmic mistake.” Ideologically, the Time Variance Authority sees variants — people who have acted in some way that diverges from the intended flow of time — as “cosmic mistakes”: living aberrations in need of correction or violent erasure. In order to uphold “the Sacred Timeline,” the TVA censors reality. Much like the TVA criminalizes variants, societies often criminalize queer existence. For trans people, there is no Gender Variance Authority — no single bureaucratic organization in charge of punishing us when we don’t follow strict gender norms. However, our bodies are constantly at the mercy of bureaucracies which decide things like gender on passports, legal name changes, or if we meet the necessary criteria for hormone therapy. Over one-hundred of pieces of anti-trans legislation (controlling everything from bathroom use to sports to medical care) have been introduced in 2021 alone. Beyond this, our bodies are policed by other individuals, and even other trans people, all of whom judge if we are “trans enough” or in fact the “correct” gender. Even though nonbinary genders have existed for thousands of years, queer histories are often destroyed and schools in the USA continue to prevent them being told. In cases like the Hays Code in film or Comics Code Authority in the comics industry, our stories are censored too. Being seen as a threat to the natural order of things (much like variants) means we’re at risk of both physical and psychological violence. In the face of hate groups like the Westboro Baptist Church, it’s easy to start feeling like a “cosmic mistake.”

Loki gets arrested by the TVA for time crimes

As Sylvie confesses to Loki in episode 4, “Everywhere and every-when I went, it caused a nexus event. Sent up a smoke flare. Because I’m not supposed to exist.” As queer writer and poet Saeed Jones (@theferocity) wrote/translated on twitter on June 30th: “Someone being told they have committed a crime they didn’t even KNOW it was possible to commit — just by trying to live their life in a way that makes sense to them — perfectly sums up what it’s like growing up queer in an anti-queer society.” Or, as Jessie Gender more succinctly put it, “Time gods? Societal stigma? Same thing.”

Loki posits the question “What makes a Loki a Loki?” early on and throughout its run offers a host of answers. One definition Tom Hiddleston’s Loki offers in the fourth episode is: “We may lose. Sometimes painfully. But we don’t die. We survive.” In the introduction to her translation to The Odyssey, Emily Wilson says of Odysseus: “For this hero, mere survival is the most amazing feat of all.” Loki, taken as a nominal hero, is much the same. In the face of a universe dead-set on extinguishing him, Loki is defined by survival.

Loki’s survival is at its most blunt in episode 5. Having survived a fourth “death” at the end of the fourth episode (after saying “I’ve died more times than I can count”), Loki wakes in the Void, a place outside of time where the TVA sends variants to die. Loki quickly learns the Void is, in fact, overflowing with Loki variants. While the show may undercut Loki’s genderfluidity in the same episode, the show’s third episode had suggested that all Loki variants are bisexual. Any way you cut it, the Void is filled with un-killable queer people. And as Richard E. Grant’s Classic Loki explains to Hiddleston’s Loki, “Lokis survive. That’s just what we do.” Later, when Loki is fretting about what they can do in a powerless situation, Classic Loki reiterates: “Survive. That’s all there is. All there ever was.” There’s certainly some irony in the fact that Classic Loki later dies, but his point remains.

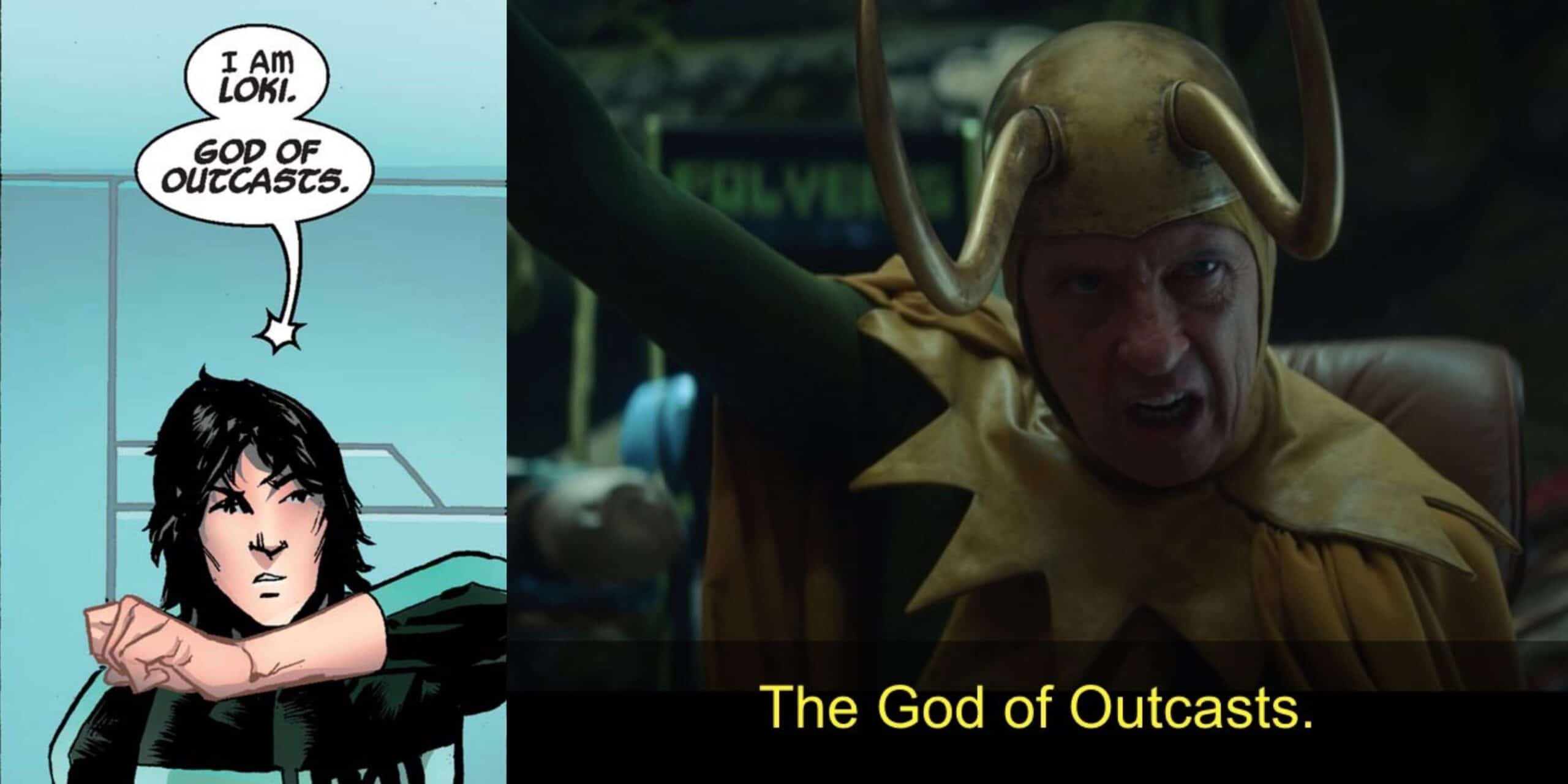

Processed with MOLDIV

Loki isn’t just a survivor: he’s a marginalized person on both the basis of his queerness and the fact that he’s a member of a marginalized (fictional) race (the Frost Giants). Also in the show’s fifth episode, Classic Loki calls all Lokis “God of Outcasts,” recalling the 2019 Loki comic by Daniel Kibblesmith. Kate Herron stated on Twitter that she gave a panel from this comic to Hiddleston on the first day of filming, showing that the series did indeed mean to emphasize this name and idea. As in the comics, this Loki has been thrown “out of universes.” As I explained in the second article of this series, this title — “God of Outcasts” — frames Loki as both a marginalized person and our defender. Taken together, part of “what makes a Loki a Loki” is a specific form of survival: that of marginalized people.

Loki, at its crux, is a story following a bisexual and (nominally) genderfluid character, whose existence is criminalized, trying to survive. It’s ironic that a show about a queer character threatened by erasure participates in erasing his queerness. The show, by letting Loki be more overtly queer, rather than erasing his genderfluidity, would have made the show’s themes of survival and of personal transformation that much more powerful. Instead, queer viewers are predominately still stuck searching for subtext.

“That’s Not Who I Am Anymore:” Trans-lating Sylvie

Please note: everyone cited in this section is trans.

In this subtext lies another layer of queer-coded survivorship allegory: Sylvie functions on a level of trans allegory that Hiddleston’s Loki doesn’t. However, unlike Loki in the comics or myths, she must be translated as trans, rather than have a narrative that lets her be trans.

It begins with her costuming: Sylvie’s broken horns are a direct visual reference to Loki: Agent of Asgard when Loki reappears to his friend Verity following ego-death and assures her friend: “I am always myself” while casually shapeshifting genders. Sylvie’s horns thereby draw attention to one of the comic’s most trans moments, as well as the genderfluid representation the MCU jettisoned.

Loki in Loki: Agent of Asgard #14; Sylvie in “Lamentis”

That said, it’s her story more than her costume that truly makes Sylvie feel trans. Throughout both episodes two and three, Sylvie is adamant about not being called Loki. As she tells Loki himself, “That’s not who I am anymore. I’m Sylvie now.” She calls her name an alias, but as many trans people have noted (including YouTubers Jessie Gender and Council of Geeks, and writer/podcaster Faefyx Collington): Sylvie treats “Loki” like a deadname (a name a trans person is given at birth that they feel no longer fits them). Her aversion feels visceral. Dysphoric. However, her renaming feels survivalist and never radical or affirming.

More even than Loki, Sylvie grew up with an existence under threat. Loki is given an explicit reason for why he’s a variant (stealing the Tesseract). When she was taken by the TVA as a young girl, Sylvie was given no such explanation. Because Loki regularly places emphasis on the fact that she’s a female Loki variant (the scene from episode 5 included), it’s implied that she’s a variant because of her gender. If that’s the case, then Sylvie is like multitudes of trans people: persecuted because her gender is at odds with what the dominant ideology demands it should be.

Journalist Katelyn Burns wrote a poignant blog post on how she related to Sylvie’s story, specifically how Sylvie’s capture resonated with her own childhood fear of being found wearing the feminine clothes her mother had put in storage: “Would my parents decide they didn’t want me anymore? Would I get hauled off to face some grim-faced bureaucrat? Would the police come for me?”

For author Julia Serano, trans activist and author of Whipping Girl, part of what makes Sylvie feel trans are the transphobic reactions to her. In the series, Serano asserts, some people may be “squicked” (aka disgusted) by the romantic relationship between Loki and Sylvie because they see Sylvie as a man.

One of the underlying problems with Sylvie’s transness is its negative framing. As noted above, Sylvie’s gender exists not as something to be loved or celebrated but almost exclusively as something she and the people around her — even people who are, fundamentally, her — are in conflict with. This is one of the show’s greatest departures tonally from Loki: Agent of Asgard. AoA creates a gender-affirming — even gender-euphoric — environment where Loki’s gender is affirmed and never up for debate. (To a lesser extent, Kibblesmith’s comic series does the same.) Sylvie is defined by negative experiences like deadnaming and oppression. Survival stories are incredibly potent and powerful, but with Sylvie, gender itself can be survived but never celebrated.

Loki and Sylvie kiss in “For All Time, Always”; Loki comforts his alternate timeline future self in Loki: Agent of Asgard #17

Limits of Metaphor

The only person seemingly capable of loving Sylvie completely, taking her gender as part of the full package, is Loki. Loki and Sylvie’s relationship has been described by the creatives behind the show as a metaphor for self-acceptance. He’s only capable of seeing his own value via Sylvie (though I’d argue the show doesn’t fully make this apparent). A decent number of trans people including journalist Burns have described the relationship between Loki and Sylvie as one of learning to love and accept yourself as another gender: “it was deeply symbolic that the moment Loki fully embraces his love for Sylvie, his female self, the universe explodes into a multiverse, with all its scary and potentially wonderful possibilities.”

For me, personally, the metaphor flounders, even when taken without the specificity of gender. Their teary-eyed kiss, potentially a moment of self-acceptance, is undercut by Sylvie’s immediate betrayal. While it’s possible this could change in season 2, currently the metaphor for self-love seems to be “Loki learns to love himself in a whirlwind-romantic light but ultimately betrays himself.”

When Loki creates its metaphor, it does so while pulling thematically from Agent of Asgard without understanding why AoA’s version of the metaphor worked. The two stories are in some ways similar: in AoA, Loki learns to love and accept himself after meeting a (terrifying) version of himself from another timeline. The final moment of forgiveness, reconciliation, and self-love is represented as a forehead kiss between the two Lokis. Only then is Loki truly able to take control of his fate. Loki’s story ends similarly with a teary-eyed kiss and Loki attaining free will. However, Loki’s and Sylvie’s relationship is firmly romantic, ends in betrayal, and has been described as “twisted” and self-absorbed by the protagonist’s best friend. (Romantic attraction isn’t superior, and isn’t a form of attraction that aromantic people (for example) can relate to.) AoA’s final kiss — also a moment where Loki chooses to move on and isn’t simply forced to — isn’t undermined by betrayal: after a comic which has seen Loki as the main antagonist and protagonist both.

With AoA, the story of self-love and self-acceptance wasn’t explicitly attached to Loki being trans, but his story could still be translated as trans. This is true of Disney+’s Loki as well, but without explicit representation alongside it. As a trans metaphor, it lacks the context that AoA made unmissable via continuous focus on Loki’s genderfluidity and his own ability to love and accept it before the story even began. Loki tells something safe: a story where trans audiences can translate themselves into the story without the text giving it away to anyone cis. Neither story forces audiences to understand queer allegory, but only AoA fully represents Loki’s queerness, taking into account both bisexuality and genderfluidity. All of Loki’s queer allegory, if intended, is buried.

Much like Loki, though, queer people crave lives and stories beyond survival. We also crave seeing ourselves on screen, represented in nuanced ways: to reach the end and not simply survive but thrive. This is something I think Loki’s Time Theater scene captures all too perfectly. And in some ways the lingering sensation I’ve been left with after watching the first season. Not just having seen the good moments, the potential for better, I’ve also been reminded why its so important queer people be given control of our stories in all our variations. While Loki’s bi director might have introduced Loki’s bisexuality to the MCU, trans viewers were left to glimpse paperwork and translate the rest. Just as Marvel’s comics need to give more trans writers and artists given opportunities to tell trans stories (that go beyond aliens, deities, and villains), Marvel needs more trans people both in front of and behind the camera, as we’re the ones most capable of telling our stories.

In Variety, Marvel Studios executive VP of film production Victoria Alonso asked for patience as Marvel tries to get queer representation right. Perhaps Eternals will follow through on its promised gay kiss, or Thor: Love and Thunder on Valkyrie’s bisexuality. But queer people have spent over a decade of Marvel films and shows being patient. To put it in the words of genderfluid YouTuber Council of Geeks: “I want characters to be what they are… Either do it or don’t, because the days for hinting, the days for open-ended ‘interpretable’ representation, they’re gone. We need to move past that.” In the show, Loki assures Sylvie “we write our own destiny now.” Society at all levels — not just superhero films — needs to offer all queer people the chance to do the same: to do more than survive, to do more than pray that our survival narratives survive us.

Loki stands in the Time Theater after watching his own life and death

If you’ve enjoyed reading this and want to support me/my writing by “buying me a coffee,” you can do so at my Ko-Fi here.

Please also consider donating to somewhere like Trans Lifeline, Transgender Law Center, or The National Center for Transgender Equality.