Guest Feature by @Ali_Galactic

Ali_Galactic is Trans AF, and a rabid Blue Dad (Apocalypse) fan. Her favorite pastimes include reading X-Men comics, playing video games, and advocating for marginalized people. She can be found on Twitter @Ali_Galactic, and like many trans people, she is in need of support for gender affirming care.

Content Warning: This essay contains discussion on the following topics – Suicide, Transphobia, Gender Dysphoria, Deadnaming.

On the morning of February 26th 2020, I rolled over in my bed, turned on my iPad, and downloaded X-Men #7 (Jonathan Hickman, Leinil Francis Yu, Sunny Gho, VC’s Clayton Cowles, Tom Muller). Downloading the week’s new X-Men comics had become a kind of ritual for me every Wednesday since House of X and Powers of X came along and suckered me back into the world of the X-Men. The buzz about it was firing on all cylinders as fans heard whispers of something big going down — something that might re-contextualize how we thought about the X-Men and the mutant culture being built in the newly founded mutant nation of Krakoa. Needless to say I was excited and hyped up, but… I never expected what we got. Even now, more than a year after its publication, this comic book still has the power to bring me to tears. What on the surface might seem like a story of a brutal ritual suicide actually contains an effective and revelatory tale of affirmation, self actualization and acceptance.

The issue concerns the first Crucible on Krakoa, a newly created ritual by which mutants who lost their gifts at the hands of Scarlet Witch on M-Day. As such, The Crucible is an engine of rebirth which allows mutants stripped of their powers to reclaim their identities and face the pain that being deprived of their sense of self brought with it. They must self-identify, self-affirm, and self-actualize themselves as mutants in order to be reborn free of the baggage of having their identity taken away from them.

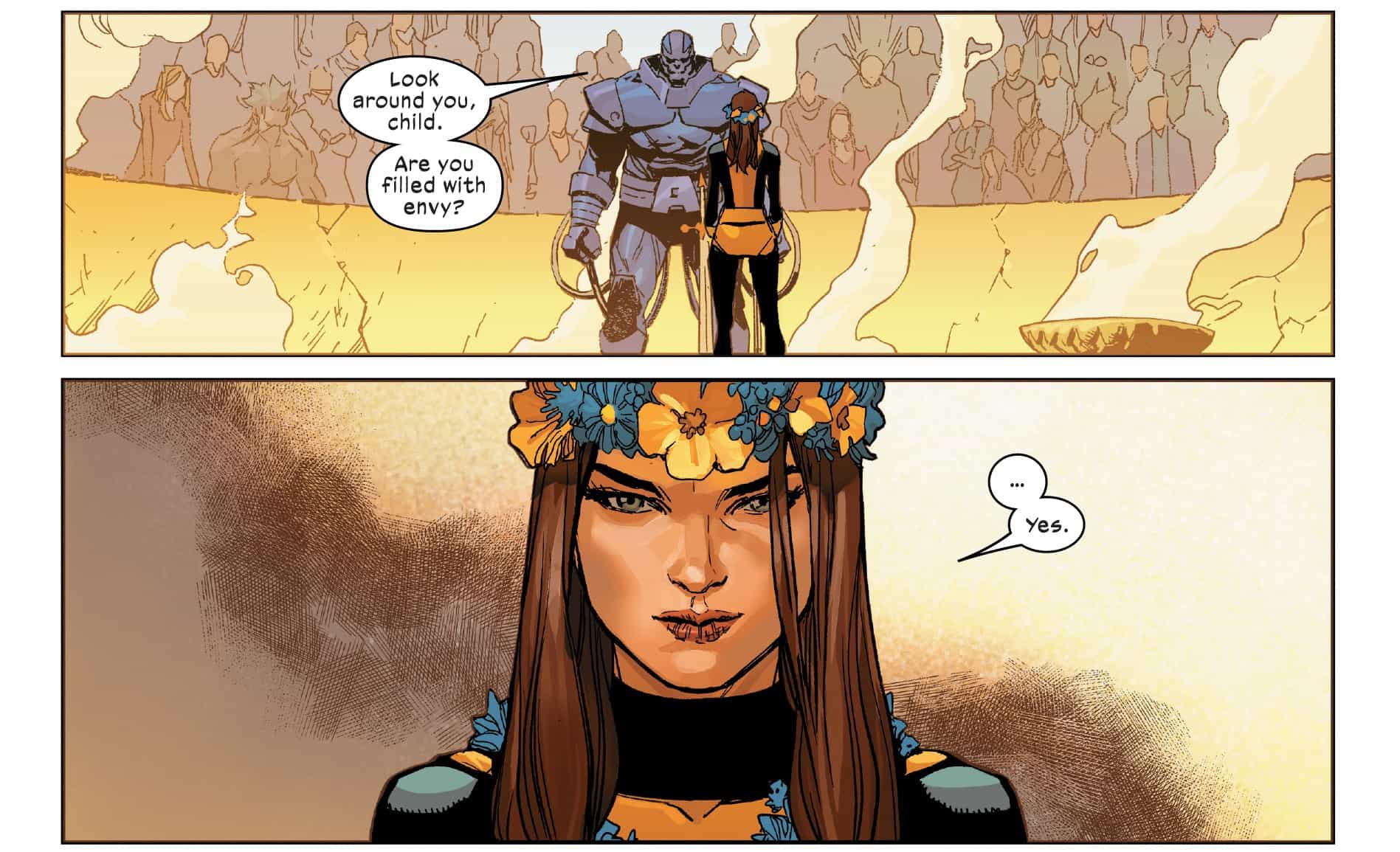

The ceremony starts with a former X-Men villain turned Quiet Council Member, Apocalypse, and Aero, a Guthrie family sibling who was depowered on M-Day, in the center of a grand arena. Many of the mutants watching are terrified at what they’re about to witness. They don’t understand why it’s so important for her. They don’t want to watch her go through it. They don’t want to bear witness. But this isn’t for them. It’s for Aero. The arena stands are filled with mutants of Krakoa who’ve come to see the ritual. Apocalypse breaks the silence with a speech about humanity and how they’ve treated and viewed mutants throughout history stating: “Humans. What can we say about humans that they have not already said for themselves? They cover the truth with lies, but their actions — their godforsaken actions — always reveal who they really are. Oh, how they hate us. Oh, how they fear us. Oh, how they envy us.”

Towering over Aero he’s prodding her, attempting to get under her skin and give voice and presence to her doubt, and fear, and her trauma, to help her face it. As she stands there, within his enormous shadow, admitting the envy she feels being surrounded by mutants, and the baggage of her mutant identity stolen — a new human one forced upon her.

This envy of a life I could have had feels way too familiar. As much as Aero is the victim of circumstances outside of her control, so too was I forced to live and perform a constructed gender role because of an arbitrary decision made by a doctor on the day of my birth. Made to suffer with all the baggage, and expectations, and performance that a simple phrase — “It’s a boy!” — placed upon my infant shoulders. Expectations that were hammered home by someone checking the “M” (for male, not for mutant, sadly) box on my birth certificate as it was issued. So too M-Day ripped Aero’s identity from her. Yet here she stands — facing down someone who for decades has been one of the X-Men’s greatest foes, defiant and with confidence — because she knows who she is.

But it’s not over yet, as Apocalypse then escalates his attempts to rattle and upset Aero by narrowing his focus to something more personal, her name.

Names are very important in our society and language. They tell us what things are, where things are, who people are. Apocalypse is now directly challenging who and what Aero is. But she knows who she is: Aero is her name. It’s who dreams while she lays asleep at night and who wakes in the morning to face the next day’s challenges. In questioning her name, Apocalypse is questioning the very core of her identity, and he even goes so far as to weaponize her family, giving voice to the doubt and shame within her.

So too did I go through my days pre-transition associating with my name. Ali Isabelle Selby. The name I gave myself as I began to explore and accept that I am a trans woman, and the one that I had legally tied to myself decades after coming out publicly. It’s the name that has been treated as a joke by those seeking to hurt me, those seeking to cause me to doubt myself, as if they could snap me out of some delusion which had overtaken me in an effort to prove that I don’t know who I am. In pulling this card, Apocalypse is standing in for Aero’s own insecurities and inner doubts in order to get her to push back and break free of them.

He springs this trap with his follow-up which forces her to effectively deadname herself only for him to drive home his point – that the identity that was forced on her defines her, rather than the one she seeks the claim. It’s a cruel trap to spring on someone who is on the precipice of self-actualization. Someone who already had the nerve to step into the area and proclaim who they are, and it’s one trans people also experience many times throughout their lives.

‘Deadnaming’ refers to the act of calling a trans person by the name given to them at birth rather than their actual chosen name. Our deadnames are often weaponized against us to cause pain and anguish and to inspire embarrassment or shame. Family members might cling to them out of a misplaced sense of mourning or loss which can cause us to feel guilt in a cruel twist, as children are often raised being told “Don’t worry! Just be yourself and everything will be fine!”. They’re also used to out us in social circles where our identity as trans people may have been previously unknown to the group which can expose us to violence and ostracization. It’s a cruel and vicious act of violence, and a pain you never get used to.

After his initial attempts to unsettle her, Aero stands resolute and unmoved. She knows who she is.

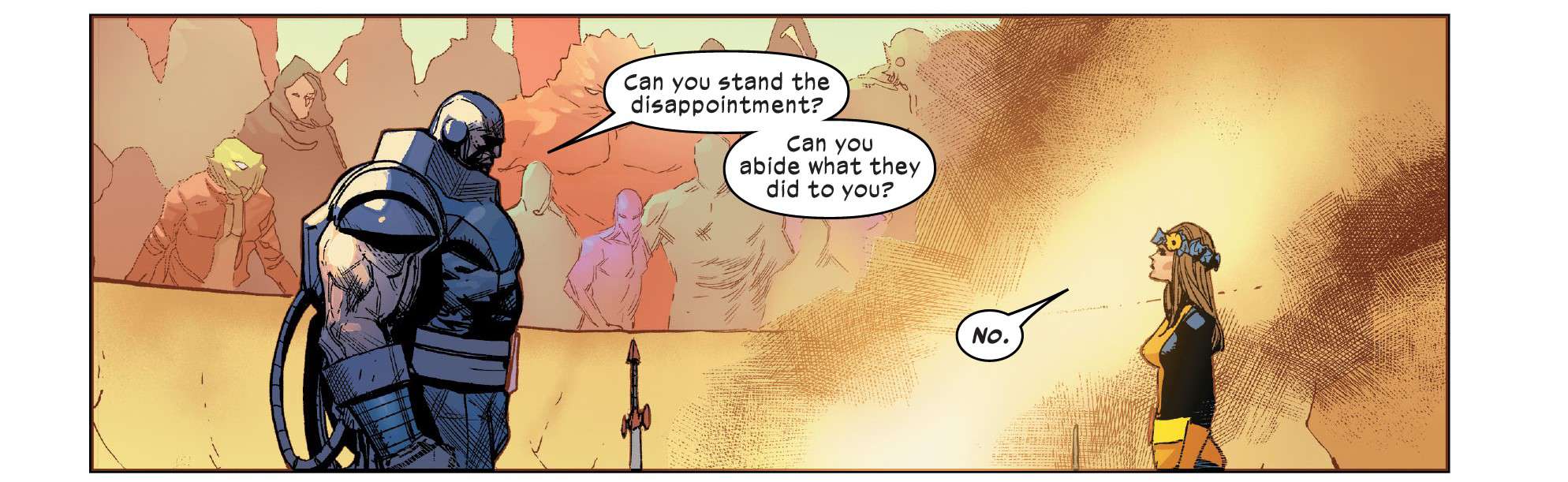

Apocalypse now sets the stage for what The Crucible means and what Aero is about to endure. “Can you abide what they did to you?” he asks and she answers firmly with “No.”

So did I when faced with this question. I knew I couldn’t abide continuing to exist inside the construct of my life that our cis-centered society had built for me. I’d seen the code in The Matrix so to speak. I knew that continuing to do so only served to uphold their imaginary version of me, to the detriment of my own conception of who I was. I’d lived this imaginary boy’s life, and been crushed under all the expectations that that life brought with it. I knew that boy wasn’t me, and his life wasn’t mine. I knew then that I needed to be free of it. I needed to be me. Aero too knows that she can’t put herself back into that bottle. There’s a pathway to reach out and claim her identity and she cannot, and will not walk away from it.

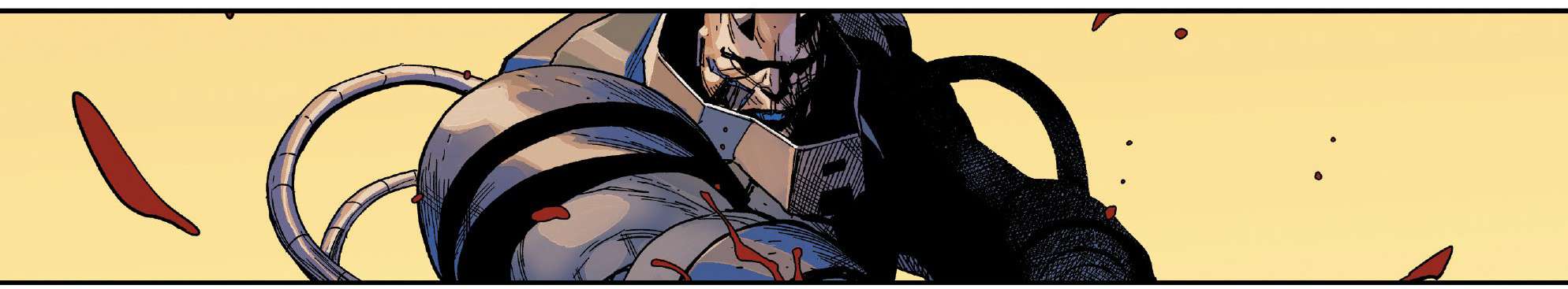

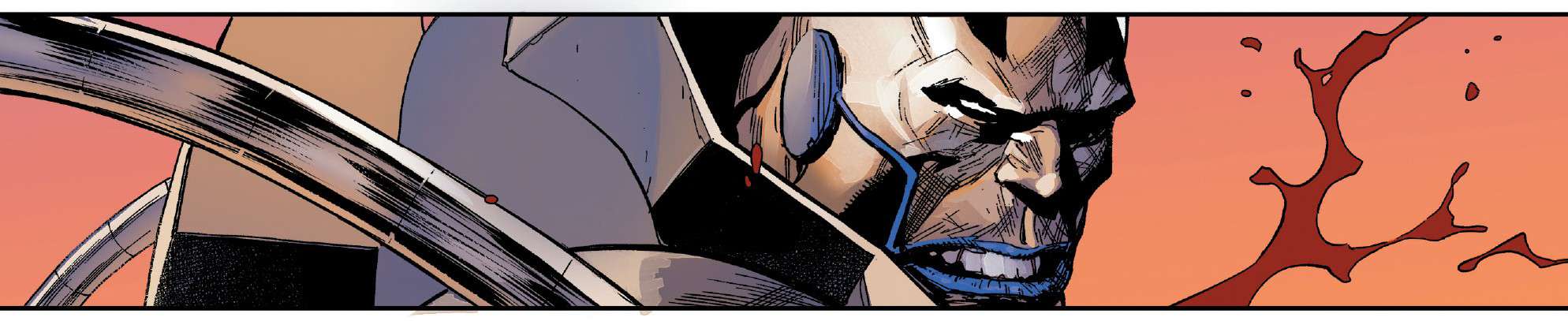

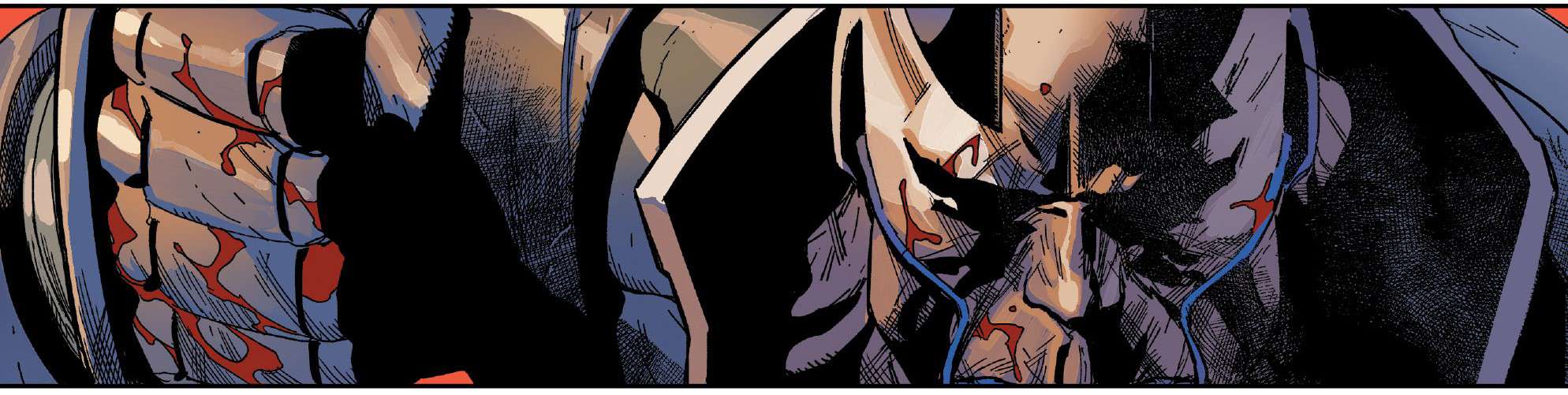

And so The Crucible begins. Aero will fight Apocalypse to the death all for her unwavering commitment to herself and her identity. No punches will be pulled, no quarter asked or given. As it begins we can clearly see that Aero is woefully outmatched. Apocalypse doesn’t toy with her, nor does she toy with him. But it’s clear who will be left standing when the fight is over. After several panels of brutal combat, with Aero now on the ground disarmed, her body bruised and broken, her blood spilled on the arena floor, Apocalypse pauses as she rises again to her feet to needle her with yet another question.

“Are you sure you want to do this? I mean, it’s expensive and quite difficult. People will hate you for who you want to be.” I’ll never forget that statement. I was seventeen years old and my Mom had taken me to see her psychologist to talk to him after having come out to her a week earlier. He asked me that question as if I hadn’t considered it before.

Depictions of trans people in the media have always been by and large woefully problematic at best and violently transphobic at worst. He wasn’t telling me anything I didn’t already know. I knew people would hate me for it. I knew it might cost me opportunities, and friends, and family. And still, I knew who I was and I knew I shouldn’t give in to those fears. But, here was a mental health professional telling me how bad it could be, and he was asking me — still a child in many respects — if it was worth it, if I could take it. Was it really so bad? To just be the man the world wanted me to be, to sacrifice myself upon the altar of society’s expectations? The fear I felt in that moment caused me to exist imprisoned by feat inside of that question for more than 20 years.

Until, like Aero … I picked myself up off of the arena floor and told that doctor and his question to go to hell.

And so, I came out. I began my transition and my Crucible continued.

“I’m sorry, sir. What did you say your name was? Alan? Aaron”

“Oh my god! Look over there? See that person by the ATM? That’s a man!”

“I’m sorry, honey. But I have to mourn the loss of my son.”

“I’m sorry, but I can’t accept you as my sister.”

With that last punch Apocalypse stands over Aero, after once again having beaten her to the ground. She kneels doubled over in pain, her arms clasped around her ribs as she begins to speak and rise to her feet once again. Beaten, and broken, but not defeated. She once again answers his question in defiance and once again digs deep within to steel herself for the next round of combat.

I’ve often described living in our society as a trans woman as a kind of death by one thousand paper cuts, or living with a constant raw nerve at the core of your being which lashes out in pain at every misgendering, deadnaming, and awkward glance from a stranger. It’s waking up every morning and knowing that at some point during the day you’ll be hurt or worse by someone you love, a stranger, a co-worker, or a passerby on the street and having the nerve to get up the next day and do it all over again.

Just like Aero, hurt after hurt, we rise again defiantly in spite of a society that is constructed and designed to be in opposition to us. Every day that false identity is inflicted again by the words and actions of that society and the fear and hatred it engenders in its populace, and every day we have to bury it once again and steel ourselves for the next.

Aero has taken her last stand and is now granted the death of her false identity. I also sought to disassociate myself from my deadname after I transitioned. I immediately changed my name on the accounts that I could, made new ones for those that I couldn’t. I spent weeks afterward exhaustively excising that false identity as much as I could from the internet, my private life, and my work place. The death of my false identity was cathartic and relieving; no longer would I have to worry about someone looking me up online, finding my deadname or old photos, and using them to out me or worse.

Aero has taken her last stand and is now granted the death of her false identity. I also sought to disassociate myself from my deadname after I transitioned. I immediately changed my name on the accounts that I could, made new ones for those that I couldn’t. I spent weeks afterward exhaustively excising that false identity as much as I could from the internet, my private life, and my work place. The death of my false identity was cathartic and relieving; no longer would I have to worry about someone looking me up online, finding my deadname or old photos, and using them to out me or worse.

I did all this while my family watched frozen in a strange sense of loss and disappointment as I killed off the man they once knew. Likewise, throughout the ritual Aero’s family and friends looked on in horror at what she was put through in order to attain her true identity. They can be seen holding each other back from jumping in to save her. Her sister, Husk, is so gripped by the horror of her sister’s impending doom that she’s unconsciously ripping her own skin from her face in the moment that Apocalypse administers the death blow. My family and friends are often horrified by the treatment and surgeries I wish for in order to feel more at home in my body. In describing such procedures and treatment they recoil, and wonder aloud why I would seek that out and if it really is that important. Like Aero’s family, they are horrified at the process, and struggle to understand the necessity of what they perceive as nothing but pain and brutality.

Moments after her death, Aero arises once more. Resurrected as a whole and complete person, a mutant once again. What follows is the reveal that manages to bring me to tears every time I read it: Aero returns to the arena to thank Apocalypse. We now know that Apocalypse’s motive in being there with Aero in The Crucible was not out of malice but rather out of support.

He wasn’t antagonizing Aero, he was standing in for her own doubts, and fears, and pain. If only my mom’s psychologist had been strong enough to offer this kind of support rather than discouragement. Rather than watch from the outside in horror wishing to whisk her away, to shield her from the pain of self-determination, Apocalypse stood with her, endured it with her. This is what allyship looks like to me. It’s not so simple and performative as tweeting “Trans Rights Are Human Rights.” It’s being there with us, not only in the uplifting moments, but in our difficult ones as well. It’s getting in that arena and taking some punches. It’s stepping in and correcting the clerk who misgenders us while we purchase our groceries. It’s going with us to our surgeries and being there while we recover. It’s advocating for us with the local and federal government. Just like Aero couldn’t endure her Crucible alone, neither can trans people. We need the help of our cisgender brothers and sisters. Being active participants and not passive observers.

The sad part is that all this gatekeeping and pain and sorrow and internal turmoil doesn’t need to exist. It only does because society as it exists determines it to be necessary. All of that pain can be avoided for the most part, if only our society recognized that gender identity is not a fad, or a trend, but is something intrinsically personal that forms a cornerstone of how we conceptualize ourselves whether we’re trans or cis. And, in doing so, providing treatment for trans people and nurturing our identities as early as possible. This would save us from The Crucible that is the gatekeeping infesting trans healthcare practices and providers, the laws currently being passed all over the U.S. and the U.K. which seek to criminalize providing medical care to trans youths, or banning trans student athletes from participating in school sports, or dictating where we can or can’t pee, or attempting to prevent us from obtaining equal human rights under the law. As trans people, we must endure existing in cis-centered society, we must endure The Crucible – at least for now.

X-Men #7 is dear to me because it so perfectly encapsulates my experience of transition in our society. It’s cathartic to read and serves to remind me of all the wonderful and brutal ways that transition has affected me and impacted my life. In doing so, the issue doesn’t just focus on the pain and trauma, but on those positives as well. Transition has been both affirming and painful: I’ve experienced a loss of familial ties, friendships, financial opportunities; but I’ve also opened doors to new and fulfilling opportunities, built new friendships, and found a family that is dear to me in ways my blood family never was or could be.

Unlike Aero, I can’t experience The Crucible in just a few minutes and be resurrected whole and complete (So much for the mutant metaphor, amirite?)… At times it may feel like my Crucible will never end but I know that one day I will arise with a tearful smile and fly once again.

I see you, sister. We all do.

Closing note: During the writing of this essay trans people have come under legislative attack in the United States and the UK like never before. We’re facing what amounts to a legislative genocide bent on removing our visible presence from society, and forcing trans children to endure what amounts to state sanctioned abuse. There are more than 100 anti-trans pieces of legislation moving through state legislatures in the United States alone. Please, write your state congress and governors and tell them that trans people need support and compassion, and ask that they vote against these bigoted pieces of legislation. You can also take action to help trans people by donating to or promoting the following advocacy groups and campaigns:

My Sistah’s House: Advocacy group in Memphis, TN which provides housing and home ownership to homeless Black Trans Women in order to help them get established and back on their feet.

Free Ashley Now: Ashley Diamond is currently incarcerated for a parole violation, and was imprisoned originally for a non-violent offense. Currently being housed in a men’s facility, Ashley is working with the SPLC and Center for Constitutional Rights in suing the state of Georgia for civil rights violations related to the abuse she’s endured while incarcerated and the states denial of gender affirming medical care.

TGI Justice Project: Fighting for justice for trans, gender variant & intersex people in California prisons, jails, detention centers and beyond.

Angel Rose Artist Collective is a multilingual Two-Spirit (Native American Transgender, Intersex, Asexual, Queer+)-led collective of artists, healers, educators, and advocates, uplifting Two-Spirit Nation and BIPOC Communities through art & land justice.

G.L.I.T.S. centers black trans leadership and creates holistic solutions to the health and housing crises faced by LGBTQIA+ individuals experiencing systemic discrimination at intersecting oppressions impacted by racism and criminalization, through a lens of harm reduction, human rights principles, social justice and community empowerment, imbued with a commitment to empowerment and pride in finding solutions in our own community.

The Trevor Project is the leading United States organization providing crisis intervention and suicide prevention services to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer & questioning (LGBTQ) young people under 25.

You can also navigate the #transcrowdfund tag on Twitter to help trans individuals with specific needs or share round their crowdfunding for medical needs.

This is an interesting perspective, because as a disabled trans person I found this issue horrifying. Maybe it’s because I identified Aero’s condition-having been stripped of her powers-more with my disability than with my gender. Maybe it’s because I have always understood Apocalypse as the kind of person who’d want me sterilized for the good of the gene pool, or dead for being “unfit.”

Apocalypse insults her. He demeans her. I get the impression that Aero has felt pressured into this, forced by a society that rejects the unpowered, the less able, to go to extreme lengths to become something they’ll recognize as correct. In the end, Aero has no choice but to stand, and die, disabled and weak. And they remake her-perfect, whole, without her disability. The disabled Aero is dead and gone. Forgotten. Disability has no place in the perfection of mutantkind, the genetically ascendant.