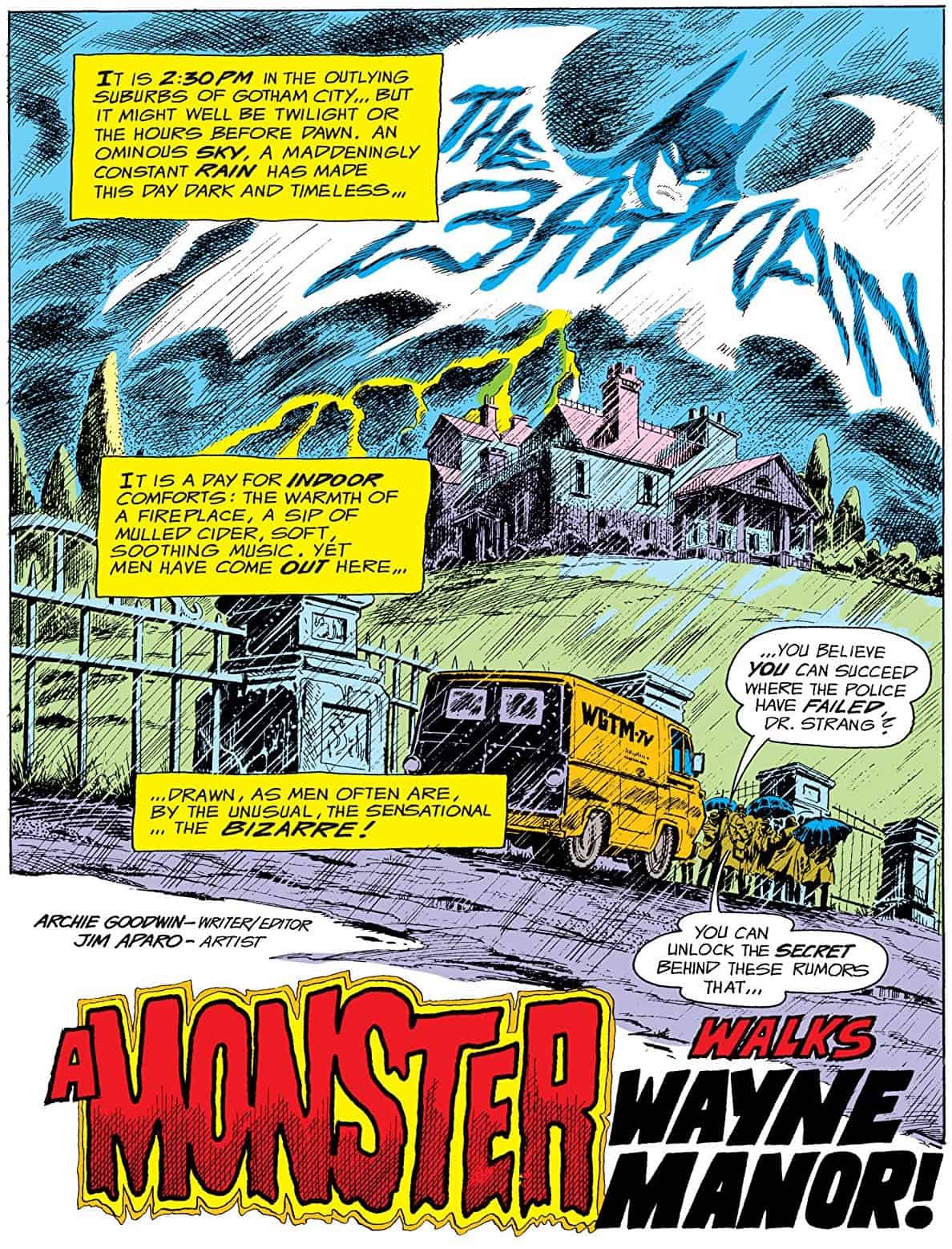

Ask me my favorite Batman story; A Monster Walks Wayne Manor!. My favorite Batman writer? I would make excuses immediately for Frank Miller, excuses for Grant Morrison, namecheck Alan Grant, Peter Milligan, Devin Grayson, Denny O’Neil, whose Batman prose I love, and make more excuses for Neal Adams, haw, hem, haw some more. Okeh, my favorite Batman writer wrote A Monster Walks Wayne Manor!. Sometimes, I am unbright.

Patricia Highsmash

In the Night, He Listens:

The Compassionate Batman of Archie Goodwin

by Travis Hedge Coke

Archie Goodwin is my favorite Batman writer. He wrote both one of my favorite cumulative takes on the character, himself, as Batman and Bruce Wayne, but also crafted stories with movement, structure, grace and energy that only grows more palpable with successive reads. Goodwin is more known for his editing than his writing, only because he was truly that great an editor. He has been called “the best loved comic book editor, ever,” by one or two or seven who worked with him. Winner of the 1992 Bob Clampett Humanitarian Award, Goodwin brought Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira to America, oversaw some of the best anthologies in comics over two decades, and turned Detective Comics into a monster 100 page per issue powerhouse with quality backups, including reprints and new material like the Manhunter comic that Goodwin did with Walt Simonson.

Manhunter, itself, has a wonderful take on Batman, a guest character in one chapter, who casts a shadow of influence over the whole. As it serialized, every chapter was a contrast to the lead Batman-centric stories. It is a solid and early use of Batman to refract an original mostly-human-superhero character.

How do you compete when you have already done comics with Walt Simonson? Archie Goodwin also wrote comics in Detective that are illustrated by Jim Aparo, Howard Chaykin, Alex Toth!

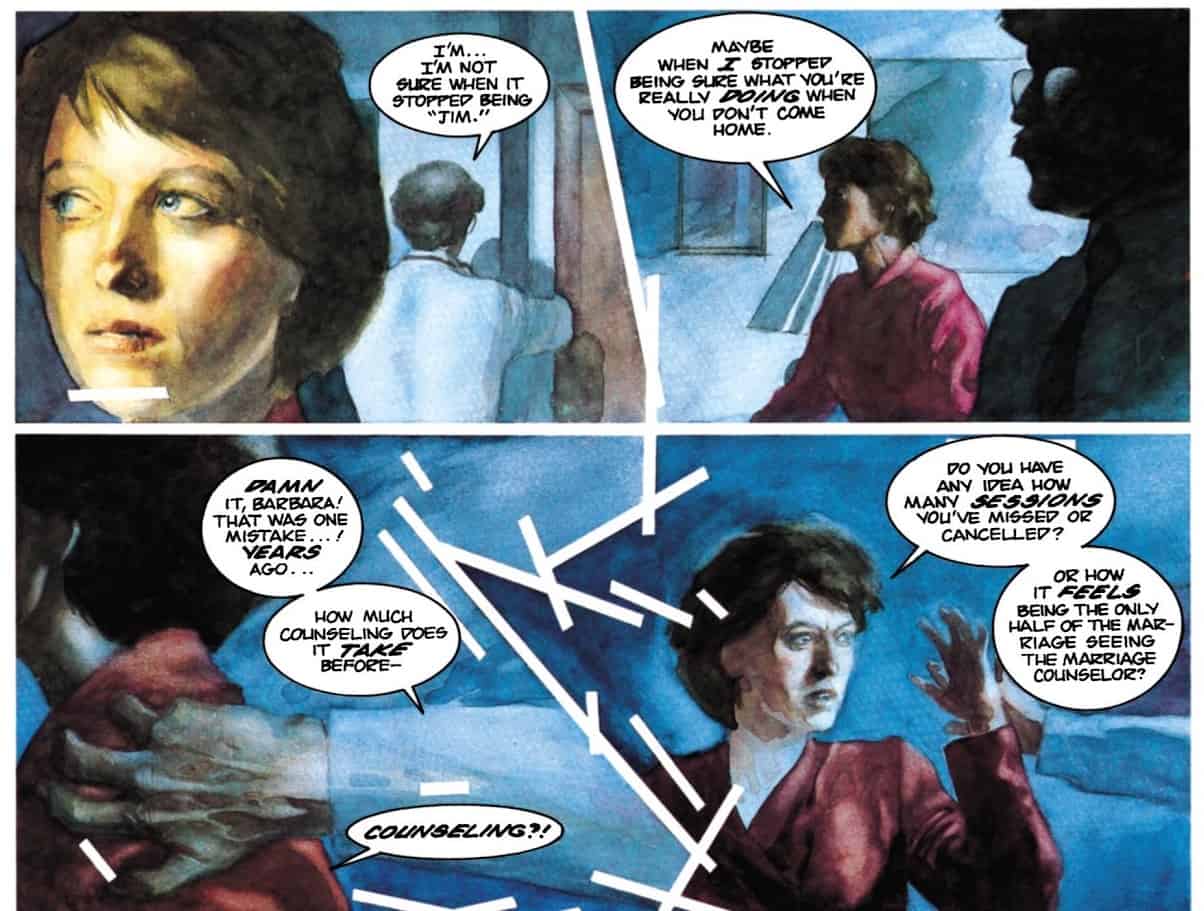

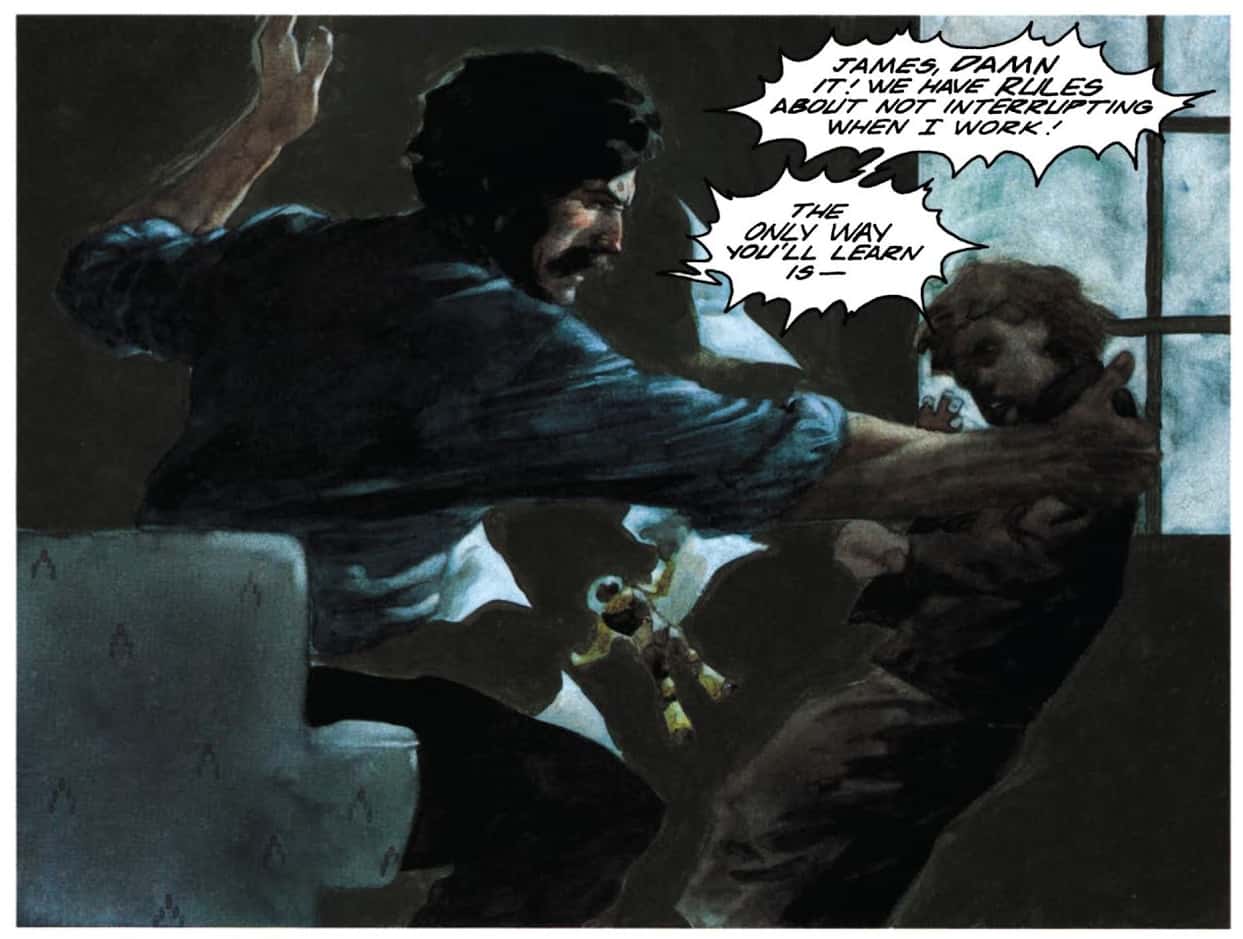

Like Milligan, Goodwin utilized almost entirely new villains, instead of a hypothetically commercially-friendly spate of classic faces. And, the supervillains were often the smaller crime, the eye pull while the more intimate and serious crimes occur. Jim Gordon, beloved, heroic, stalwart Police Commissioner James Gordon going after his child, hurting his child, is the true crime of Night Cries, which Goodwin did with Scott Hampton in the early 1990s. A few comics have presented why Gordon and his first wife split, from the idea that her alcoholism was out of control to blackmail by a maniacal child. Night Cries is the only one that does not seem cheap, or even farcical.

Night Cries hurts. We will forgive James Gordon. We will continue to smile at portrayals of him on television, to cheer him on in comics, to admire his friendship with Batman, our comic book superhero.

Goodwin never let a good hurt go. A remarkably kind man in life, he could write of cruelty and pain in ways perhaps only a nice person can. In his earliest Batman comics, our hero is reasserting the uselessness of his Bruce Wayne persona, exaggerating it to new lengths to push people away from learning his secret identity and to distance himself from his attachment to people who know him in both guises, such as Commissioner Gordon, to whom he is just repeatedly a jerk.

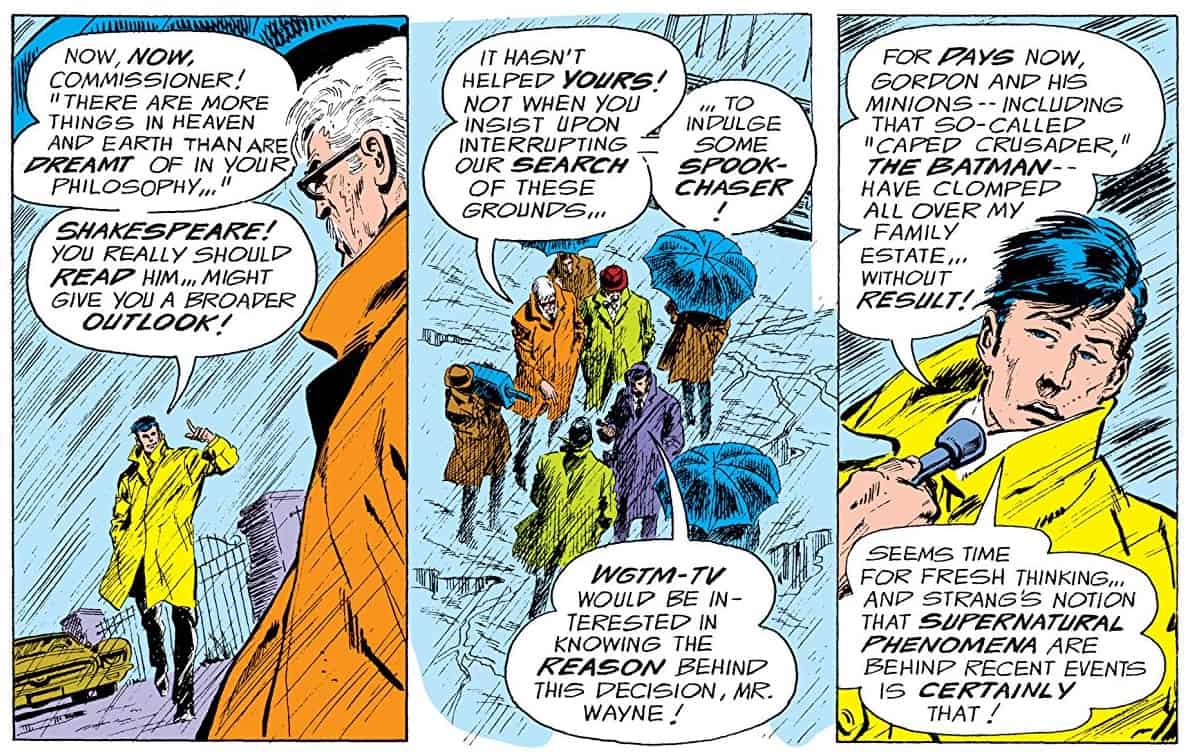

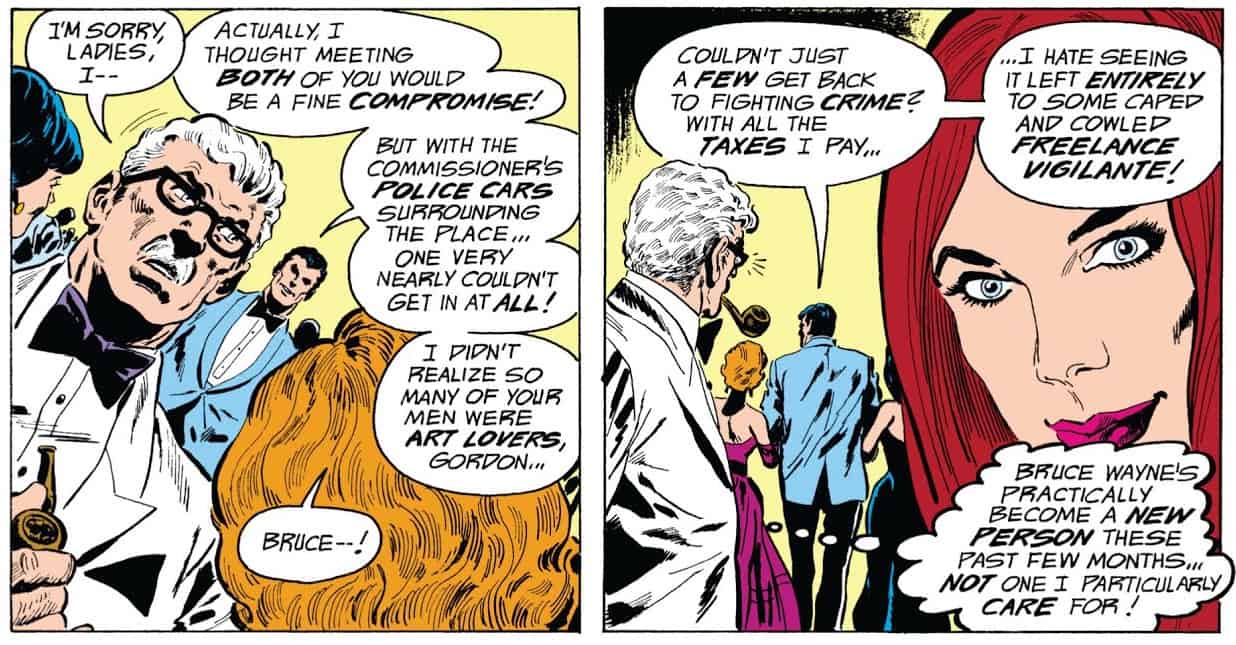

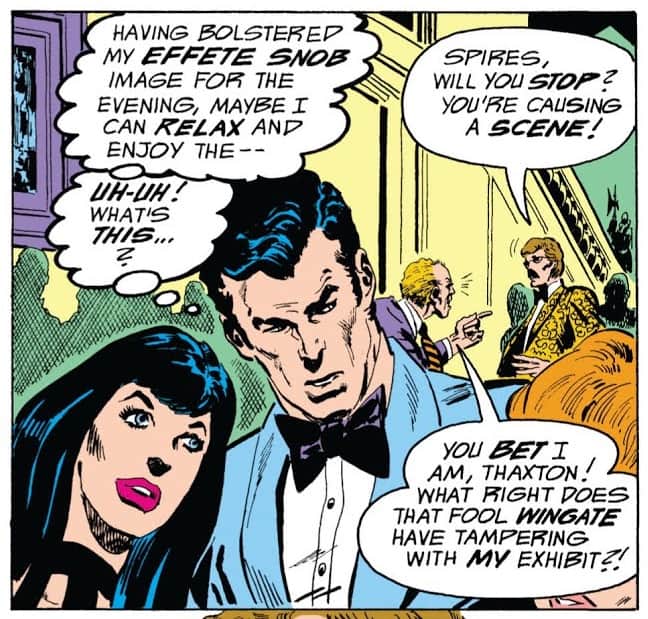

There is a scene in Deathmask!, in which Gordon is momentarily trapped between two women who each are looking for their date, Bruce Wayne. When Wayne shows up, rather than picking one or dismissing anyone, he walks off arm in arm with both women, while insulting Gordon and his police force for protecting the rare and genuinely at-threat exhibits being displayed.

When out of towners shoot up a restaurant, Bruce quickly leaps from his date and makes for the door, assuring her he is reporting this to the manager because dinner is ruined. Of course, he is to return as Batman and will eventually fight a manmade monster, a bear burned out of its home and attacked by moonshiner local police. But, for his date, this is now her Bruce Wayne story. She had dinner with Bruce Wayne and he ran like a coward.

Many Batman fans cheer at scenes such as these or, in one of the Christopher Nolan films, when he makes an absurd fuss in a restaurant to embarrass his oldest friend and her boss by buying the place instead of behaving. It is not a scene of heroism or awesome power; rich kid being obnoxious. Bruce needs to have the world see that, and specifically anyone close to him, to keep them from being close.

But, as when Bruce takes both women along with him, Bruce Wayne cannot actually be too much of a jerk. They all seem genuinely happy enough and his thoughts, indeed, are of hope that he can just relax with them at the museum; chill. His barbs at Gordon are sharp, but only sharp enough to scratch, to motivate, not to murder the guy.

Goodwin’s Escape, with art by the incomparable Gene Ha, is a Batman tale without Batman present, focusing on a new employee at Arkham Asylum going crazy while trying to get famous controlling and then owning its famous patients, those dastardly no-goods from Joker to Killer Croc. By seeing himself both as like Batman and implicitly superior to Batman, his defeat and utter collapse resonates both as indictment of our belief in Batman’s resilience and criticism of the hubris it would take to see ones methods as superior. A deliberately weird, insoluble mix that turns Escape, a very short comic, into a puzzle game that can be played on forever.

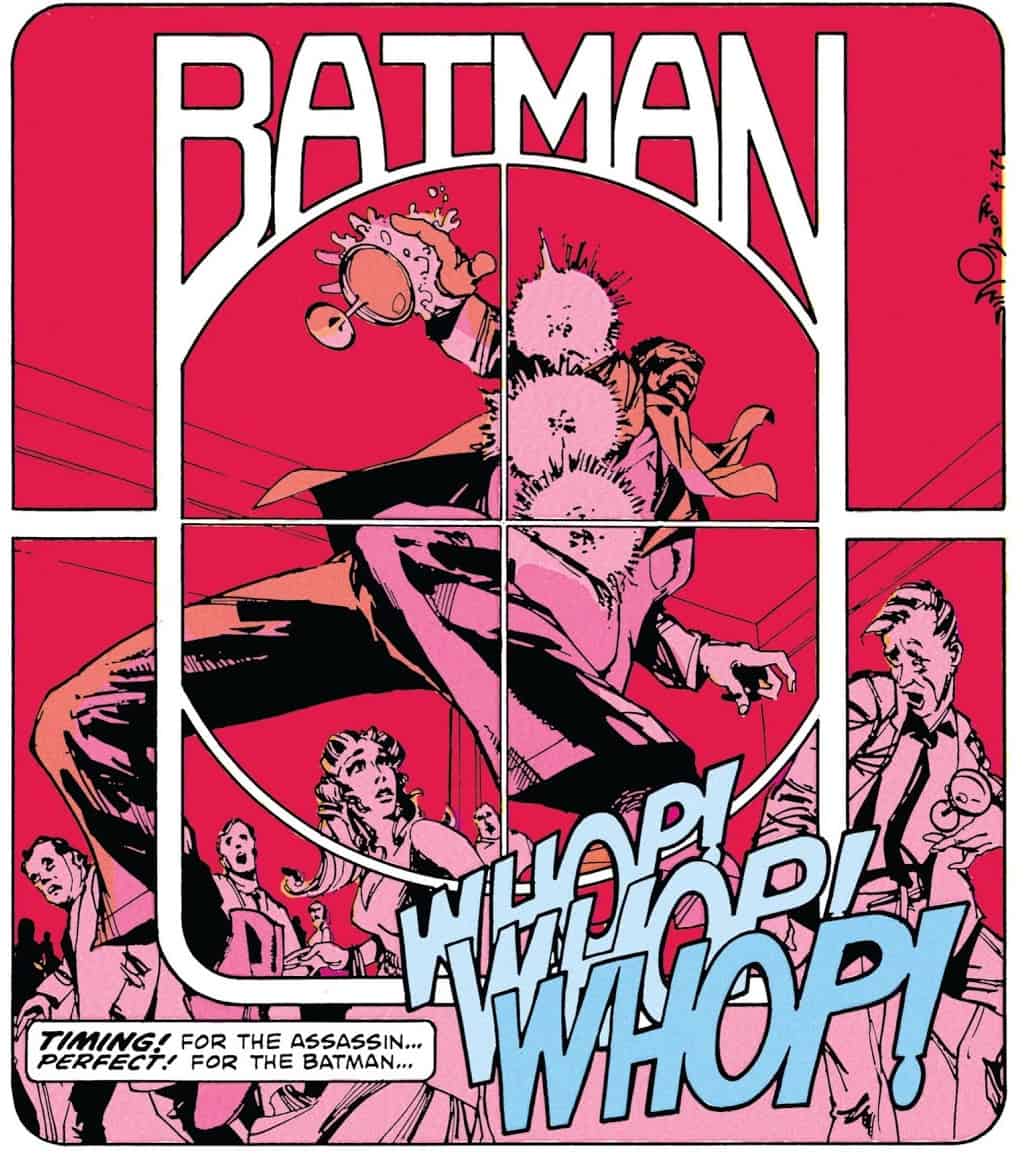

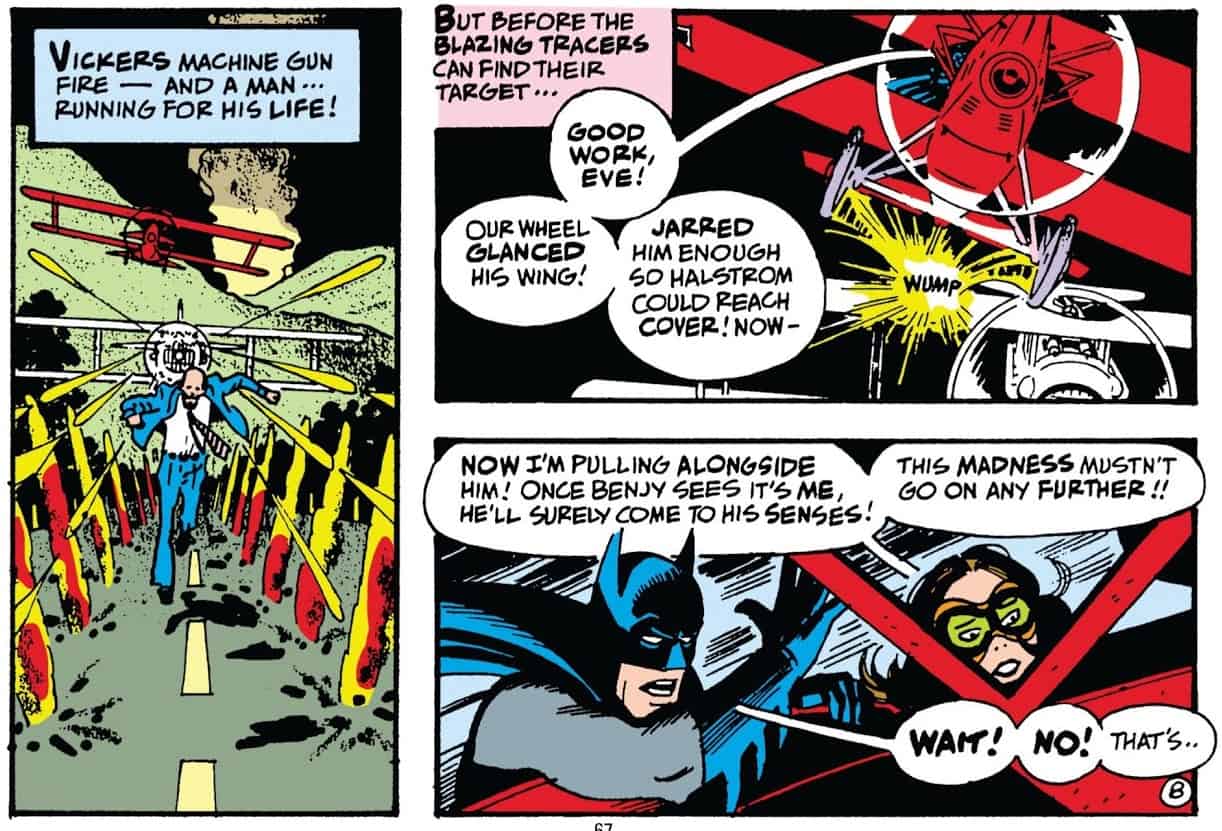

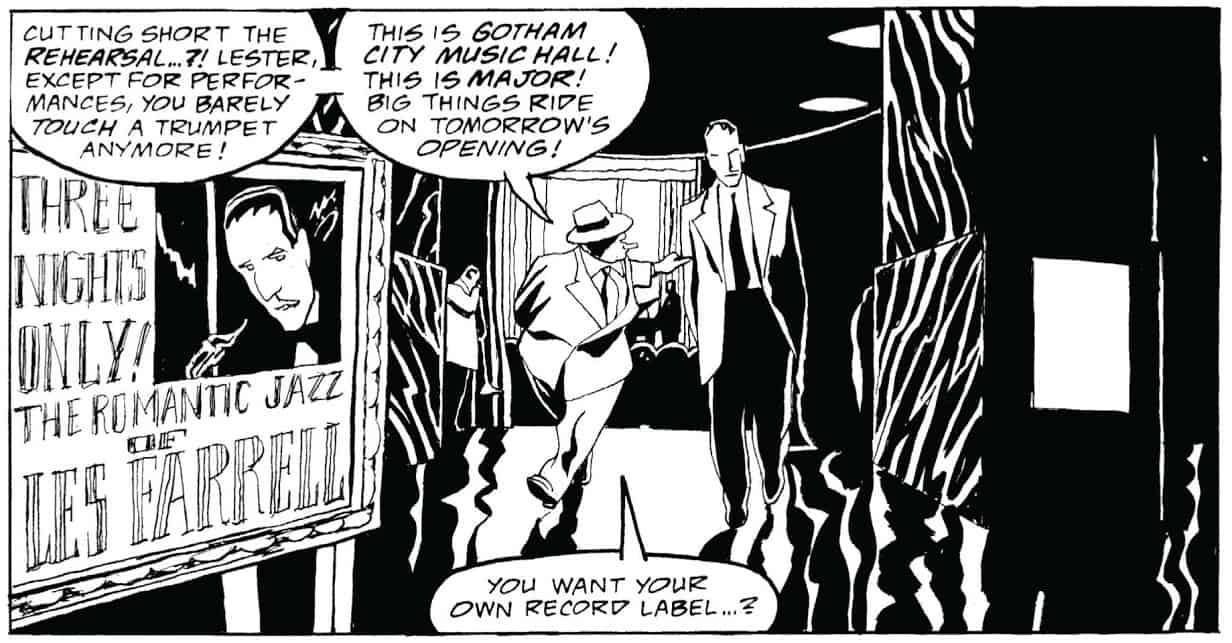

That’s another best thing about Archie Goodwin’s Batman: you can look at these things forever. Goodwin wrote comics that allowed artists to shine with their own light, to make shadows in their own shapes. What he does with Marshall Rogers in Siege is some of Rogers most full-bodied work. The dialogue-less panels and passages drawn by Howard Chaykin in Judgment Day (the comic that taught me to spell judgment without an e in the middle) look confidently modern to this day. The Romantic dynamism and balletic arrangements Goodwin achieves with Alex Toth, in Death Flies the Haunted Sky! The dense, gravitational pull of atmosphere in, The Devil’s Trumpet, his comic with José Muñoz! Nothing captures the enormity of childhood in the fashion of Heroes, with Gary Giani.

Art by Howard Chaykin.

Art by Alex Toth.

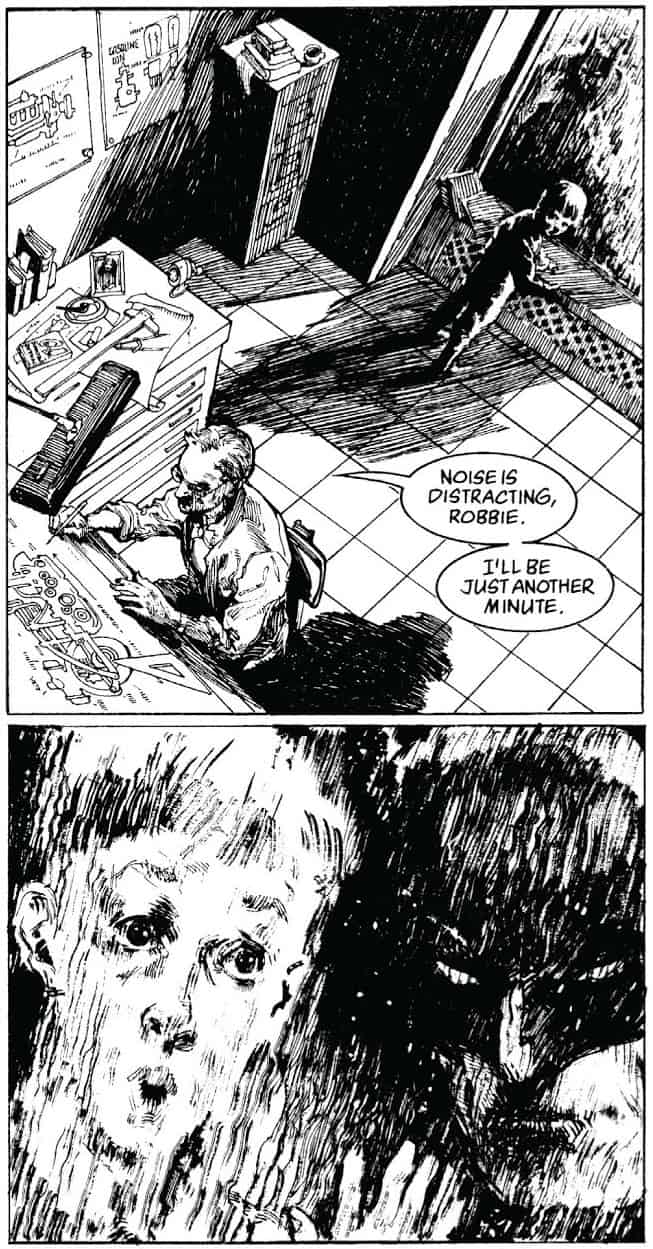

Art by José Muñoz.

Art by Gary Giani

Archie Goodwin wrote adult Batman comics for kids. These are kids’ comics. They deal with adult concerns, adult emotions, adult politics, because kids have to deal with those every day. Kids have to deal with their own emotions, politics, social dynamics, understanding of family, sexuality, and violence every day, but they are no less subject to these factors in their adult states because we, as adults, surround them with our anxieties, our indulgences, our allowances and systems.

Ghost Mountain Midnight! is not only about a young woman kidnapped by her family, to be returned home and sacrificed to a maybe-monster cursing their land. That is every kid who was ever dragged anywhere unpleasant by their family, especially by their family’s aggressive pursuit of damaging religion. It is about the rigidity of family and the old family home. It is no mistake that this story takes place during the time Bruce Wayne lived far from his family mansion, in the middle of the city instead of just outside its edges.

When friends and adult children try to take the responsibilities of their pals and parents on themselves, unto the point of self-mutilation, in Obligation, with Dan Jurgens, this is an outlet and a mirror for children, for all of us and even for the child inside many of us adults, to see the absurdity even clearer than Batman himself can. How many of the blows and burns and stabs Bruce Wayne incurs every night are on behalf of his parents, on behalf of the society do-gooders, a prominent doctor and his wife, patrons of the arts and engineering, who can no longer do good because they are dead?

Bruce Wayne is nearly defeated in Siege because he is still, nightly, donning a homemade version of his daddy’s party costume, a thing meant to be worn one night for laughs.

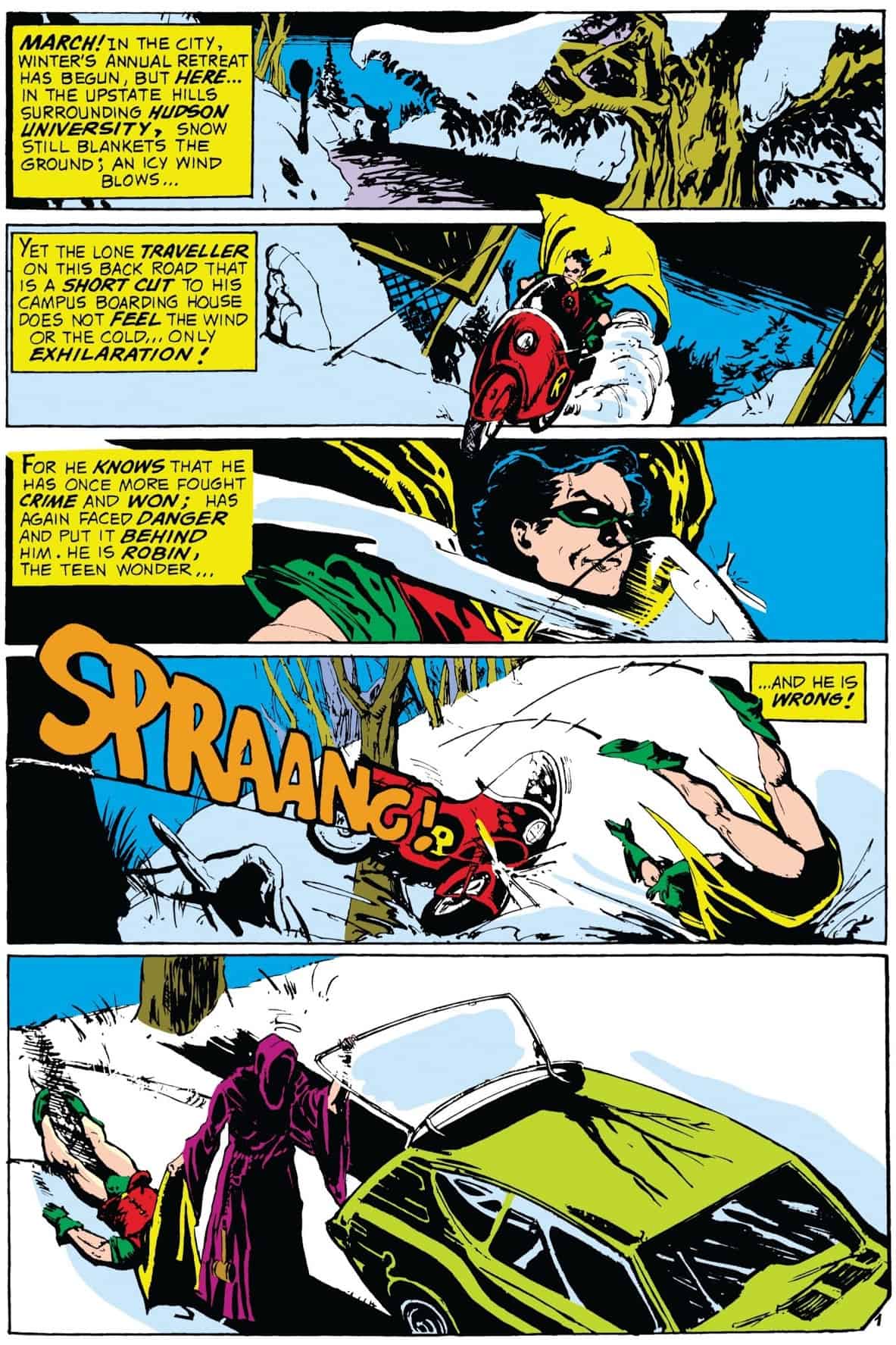

Archie Goodwin wrote Batman for over twenty-five years, and from page one to the last, his Batman is trying to save kids, young adults, old optimists, the kids and kid-inside-of-us reading the comics. He lets Alfred go look for a monster, so as not to jeopardize his dual identity, but also because he trusts Alfred, and Alfred gets hurt. He pushes at Commissioner Gordon as Bruce Wayne to stop him from being too much at risk. He relies on Robin’s resilience even as he knows he has helped put Robin in constant danger. Robbie, in Heroes, is rescued by Batman, but within the rescue, realizes his hard-working father is a good man and man who saves lives. Wyndham Vane, in Escape, that surname so close to and so mocking of Bruce’s own, has no urge to save or protect. He is every ugly criticism of Batman that does not take in enough perspective to see he is trying to save us all.

Archie Goodwin never dealt with the question of why Batman would not murder the Joker the moment the killer turned his back. Nor, any other vicious murderer or torture addict or desperate religious family on their last string before the sword of Damocles falls. You cannot save everybody if you sacrifice someone. Human sacrifice does not work.

Archie Goodwin never has to ask, in a comic, why Batman does not murder, because what kind of Batman would that be?