Patricia Highsmash

Modern Youth: The Year Larry Hama Wrote Generation X

by Travis Hedge Coke

From late 1997 to late 1998, Larry Hama wrote twelve consecutive issues of the Marvel comic, Generation X, following a beloved launch run which at the time I felt awkward for not enjoying all that much, and a shorter sequence of fill-in and perfunctory issues that wound down momentum to nil. Hama, a veteran writer, artist, editor, and all-around talent collaborated with a series of artist, letterers, colorists to put some vim, vigor, and pep back in the Gen X engine, and to aim the comic at a wider young audience. It was daring, fun, and layered, and that was probably not the best for appeasing an audience who had grown used to a routine and tone.

The classic Generation X run, the launch run of Scott Lobdell and Chris Bachalo was glib and expressionist and both heavily referenced the other x-books and fostered a sound and safe security blanket of its own kind of mutant domesticity. It was a comfort book.

Hama’s Generation X talked a little simpler, a little quieter, and it had rounder edges on the visuals, which led many readers to suspect the book had truly been downgraded to kiddie fare, and no kid wants to be caught reading kiddie stuff. What those rounded edges and bouncier narrative allowed, however, was for Generation X to deal with ethnicity in subtler ways than any X-book ever had, to deal with realpolitik and social reality without being a cynical or downer comic. Usually, when an X-book got very real world and psychological and sociological, it got dark and sharp and gloomy, and Generation X was psychology and sociology and life with grass and steak and hidden guns and stolen diaries and pookas and boojums and metaphors, traumas, and blue skies.

Generation X went from being a tween-aimed soap opera with a laugh track to a half hour of Looney Tunes shorts. When Jubilee and Chamber, two superhero teens/students, find a pooka in their campus biosphere, who sweeps them away on adventure, the vacuum is set to allow other students from the same school to find a token in the same biosphere, who, naturally, has already joined some younger children in a tea party in their tree house.

Hama’s Generation X had a heightened vocabulary, but the vocabulary was real world words, not X-Men trademarks, introducing the little-used definition for token – a creature – and words like, androgyne, to get the nonbinary M-Plate around the Comics Code and any potentially-fiddly editors.

Easy to understand and hard for a cynic to embrace, the absurdities of this run balloon outward with snarks and monsters, merging characters and other characters halved, to create space to explore the baggage every person must carry around, which we call life. Generation X was suddenly a place for commentary on Bill Clinton’s infidelities, on socioeconomic realities and disparities in what hometowns, ethnicities, family situations, and age create for each individual person.

This run is keen on presenting generations not just of adults, but of children. The run makes it clear that eighteen year olds are not fourteen year olds are not twenty-five year olds are not eight year olds are not twelve year olds. And, that eight and twelve year olds are not easily caricatured broad strokes automatons to keep a plot goofy.

This may, truly, be the first x-team comic in which ethnicity was not a special hat and boots, in which ethnicity informed outlook, heritage informed perspective, but in which being Native American, for instance, did not bring a strong mystical sense and magical powers. Synch was not the Black guy of the team or the book, but he was absolutely aware of being the Black guy whenever he was in a situation with no other Black people. The nearby town, contrary to so many other Marvel comics of the era or before, was neither all-white nor all-white-with-exception. It was diverse in ethnicities, generations, classes, and outlooks.

Which makes the goal pursued by some of the characters – intelligent, compassionate characters – of a universal amalgamation, a rendering of universal consciousness, both a holy thing and a hell of a threat. Why would characters who prize their privacy and their personal triumphs and wounds want to be universally amalgamated? How could audiences at the end of the Twentieth Century have expected Generation X to be a counterargument to Neon Genesis Evangelion and to Gulliver’s Travels?

Unlike the previous runs, or, really, most X-comics up til this point, the run is also one long story. There were arcs and crossovers aplenty in X-books, but a cohesive twelve-part narrative with beginning and end, running in an ongoing title? Unheard of. A cohesive twelve-part narrative with a beginning and ending which appears spontaneous, freewheelin’, and speeding by Casey Jones trying to make his stop in record time?

No wonder readers were split.

How could the comic move from pookas and magic trains to hate crimes like the beating of Synch into a coma?

How could this be a real superhero comic when there were not really any supervillains just weird magic animals and brothers who disagreed with sisters, mercenaries and petty thieves? An extended Snow White riff?

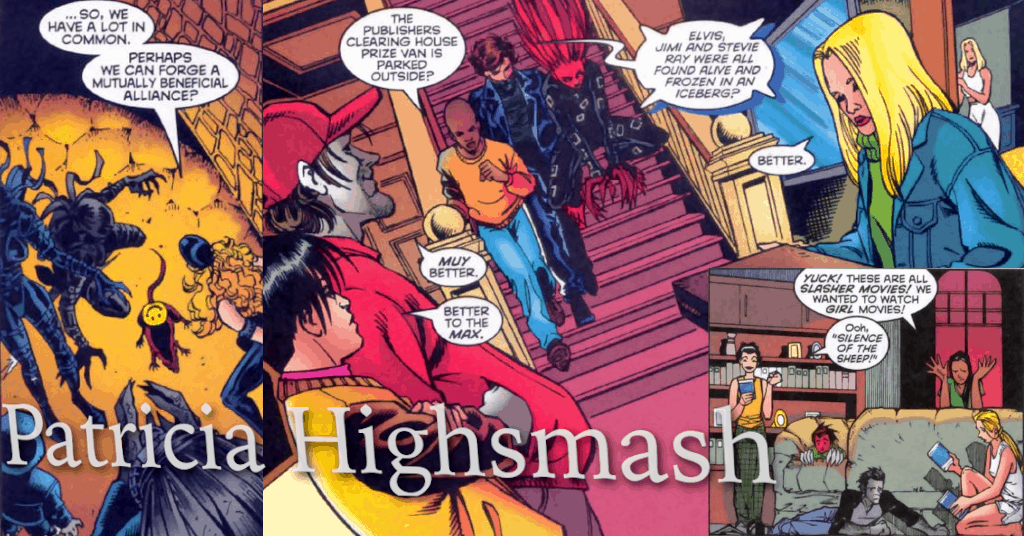

Hama’s Generation X, especially once Terry and Rachel Dodson joined as the pencil and ink team, dove firmly for pop territory. It explored and reveled in pop and parody and kitsch and the kitchen sink. When the kids watch a horror movie, the screen is a photo of Friday the 13th’s Jason. Covers show the scene half-finished, half pencils, or with then-innovative computer graphics for texture. References move from modern politics to classic myth to movie series, fantasy literature, Archie comics, and satire of the other X-books. While the main characters had never been portrayed so intimately and real, the stories and world were our world in a blender set to puree.

References, allusions, perversion and parodies piled over each other, ran each other through like stitches closing the seams of truth. The closest the run comes to a crossover with another X-title is when the ongoing, multi-issue plot is derailed by something happened in another comic that none of the characters will ever be clear on.

Reality does not need clarity or certainty to affect us, and ultimately Hama’s Generation X serves as a reminder of how subject to events and actuality we are. And, how inundated with and affected by possibility we always are.

The team’s teachers, Emma Frost and Sean Cassidy explain that the first precept for gaining advantage in a physical conflict is: “Fight only on the ground of your choosing.”

The twelve issue run is a rumination on whether or not we can. If reality gives us that choice.

The takes a lot away from Emma Frost, foremost, her psychic powers. She still drops her colleague, Cassidy, three times, with well-placed blows. She breaks a jar of mayo on the face of an intergalactic terror. She is still a force and formative.

And, the run gives a lot back to its characters. It gives Cassidy back his daughter and his sense of purpose. It gives M back her body, her life, her family. It gives characters, and us, romance. Hope. It gives Jubilee back the hat Wolverine left her and reminds us that Jubilee is an orphan who will always find, always make a family.

It gave me Police Chief Authier and his daughter, Trace, two of the first Indigenous American characters in the Marvel Universe since Wyatt Wingfoot who had no exoticized adornments and racist mystique. It is a small, subtle, and remarkable achievement.

And, when I was beaten up, so to speak, by some schoolmates who rammed with an SUV several times, a couple years after these comics were published, the run gave me something to read while my broken bones and busted flesh healed, and how it handled violence and jealousy and envy and cruelty gave me something to think about and kept me out of trouble.

We can’t ask for something big like that, but sometimes reality provides it anyway.