There Is Nothing Left to Say On The Invisibles

Robin Roundabout

by Travis Hedge Coke

Our blasphemy, our benediction, our Barbelith.

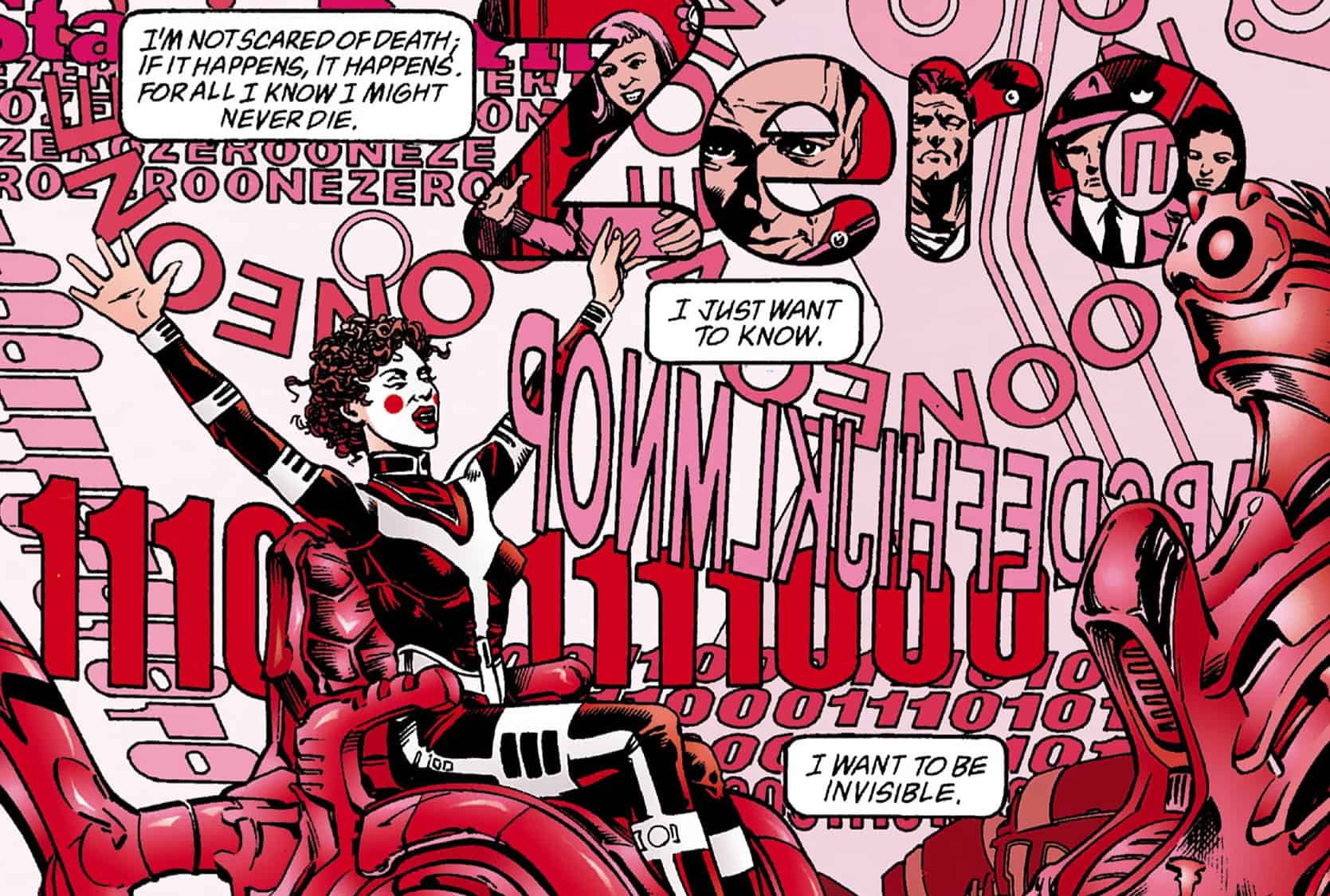

Ragged Robin is the support system in The Invisibles. Author and reauthor, it is Robin who steps in, who oversees, the placental satellite in impossible orbit. Who, but the author-audience would be an embedded remote viewer? The self-insert who is also the audience-eyes?

Robin cannot be the protagonist, or the principle point of view, because as a self-insert, she cannot directly affect too many points or her version diverges too far from record. Every human baby has a placenta, but we do not tell the story of the placenta except as it accompanies the baby or as it may be inside the parent.

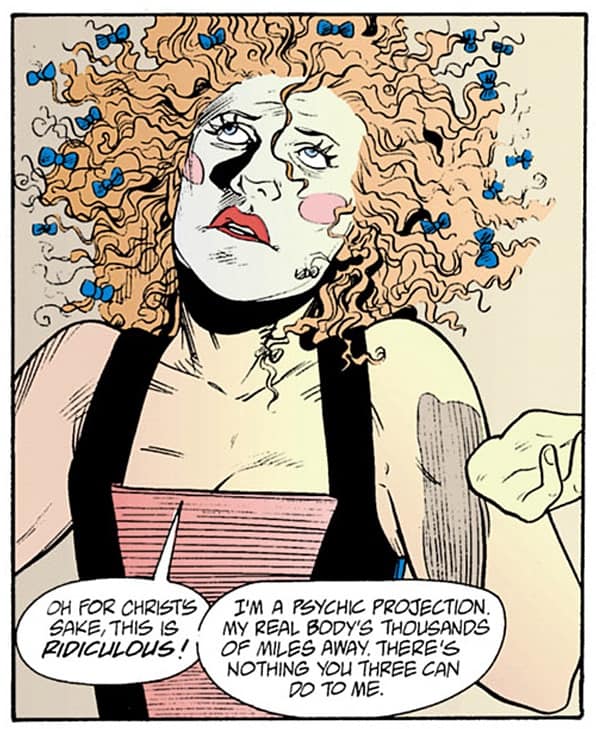

When Robin defeats Mr Quimper and Colonel Friday, and/or saves them, this is all rescue mission – all fanfiction is rescue mission -, and it is by Fanny’s direct actions and physical presence, not by Robin’s in-story physical interactions. Robin’s role in bringing the time suit to and from the 1990s is as a seemingly passive occupant. As a leader, Robin seems, primarily, to allow her cell to operate as they would. Her racing around with Boy would be much the same with or without her presence. She adds, largely, a seemingly impossible knowledge, and personality.

The direct changes which Robin affects into the world are primarily outside of physical, direct, causal action. She helps Jolly Roger to not be shot and killed. She has psychic or seemingly-psychic moments.

Is Robin psychic outside the story of The Invisibles into which she has written herself, or can she perceive their thoughts because she can write and read their thoughts?

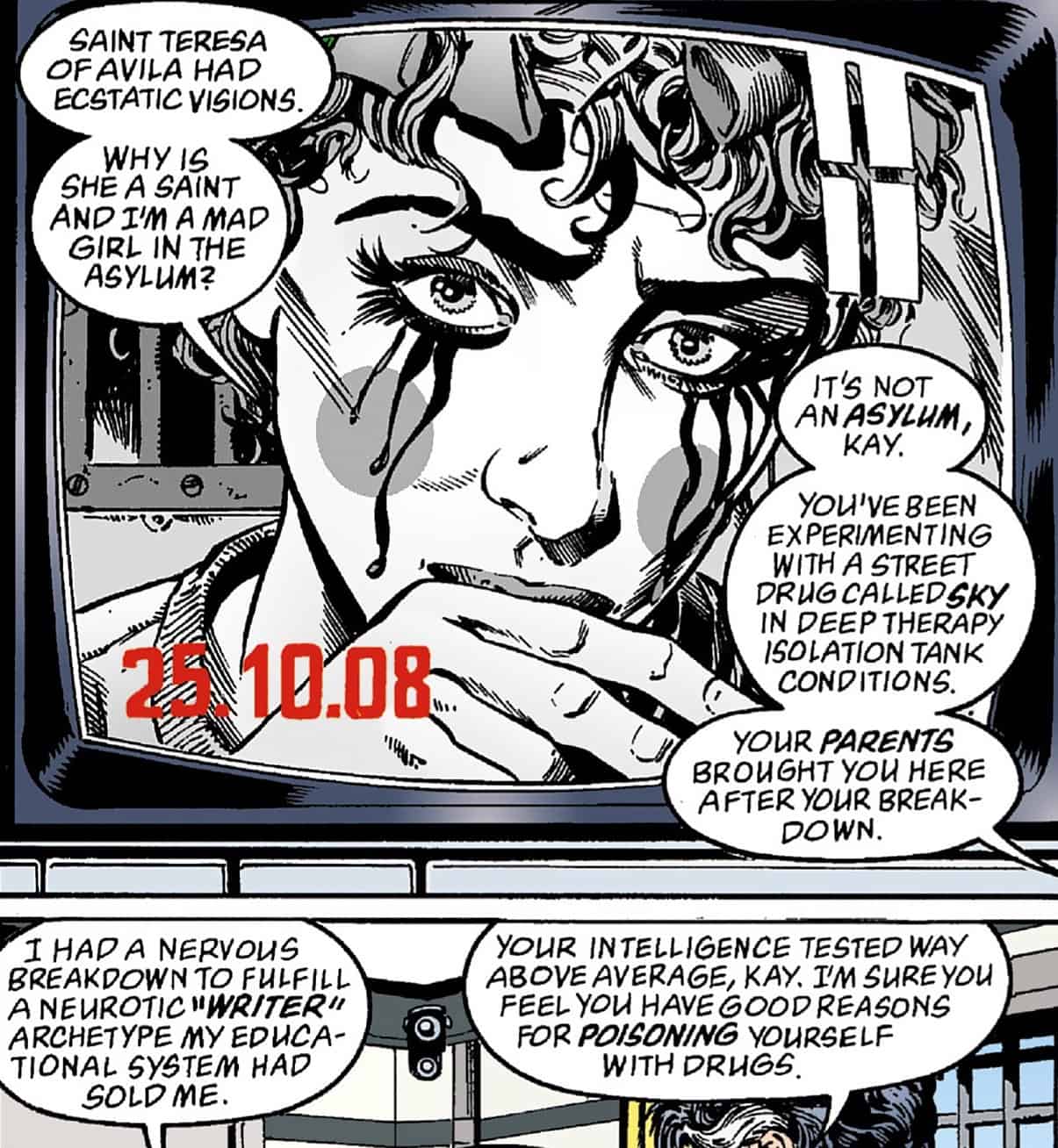

There are out-of-story reasons for Robin’s initial passive presence. Grant Morrison pitches her as a paper girlfriend for a prospective audience. “The […] type of female figure beloved of boys who read Vertigo comics.” A misaimed pitch, in my opinion. Taking into account Vertigo’s strong non-male demographic – at the time – giving some leeway to a breadth of tastes and attractions amongst the male demographic, and just me – selfishly – wanting more or better of the comic, the characters, the makers of each. I will not even make the joke that many of the boys who liked the girls in early Vertigo comics are, by now, girls.

Robin is not divided between inside and outside the story, a binary like Satan/God or Set/Horus, to be enmeshed in or embodied in a world does not contradict or contraindicate outsideness. If she has a baby, she will name them, Quimper.

Ragged Robin is trans and liminal, but not because she is liminal she is trans, or liminal because she is trans. King Mob, in his vision of a personal heaven, recreates or creates – reifies – Ragged Robin from the nerdiest of boys to the hottest of women. Fantasy figure, wank and vehicle style.

Ragged Robin is genderqueer in concept and execution.

Born in 1988, bearing a name never textually confirmed within the comic, shared by a DC Comics-owned character created by Robin’s creator, Robin is, herself, a cut-and-paste figure as well as a fanfic writer, whose fanfiction is either what we are reading or a basis for it. Raggedy Ann is a doll imbued with life. Ragged Robin is a wildflower appraised by poets, and, according to Alfred Tennyson, a euphemism for a pretty woman in cheap clothes.

The reason Robin can be an adult in the late 1990s, and yet born in 1988, is that she has traveled back in time to participate in the heyday of an Invisibles cell and Invisiblism as she, as a teenager, saw it from a fan’s perspective.

Designed by Grant Morrison and Jill Thompson, Thompson made effort to give her a nose unlike her own, to downplay their physical similarities, while Morrison, in interviews, would often encourage audiences to connect the remaining similarities between artist and creation, even after Robin experiences (or commits to) a radical aesthetic re-haul in Volume Two of The Invisibles, with its emphasis on Hollywood glam, action movie motifs, upping the erotification and objectification.

Another artist refers to the Robin of the first two years of The Invisibles, Volume One, as “dumpy,” and Chris Weston called Volume Two’s Robin his least favorite character.

“I couldn’t work out whether she was meant to be a strong female or a weak female,” Weston is quoted as saying. “She was submissive one minute and aggressive the next. She just didn’t work for me, really.”

Robin does spend much of Volume Two performing a guise, a ritual characterization, but everyone is “submissive one minute and aggressive the next.” Caricatures are only submissive or only aggressive.

It can feel like paradox for thought to become matter or matter to be thought, but thought and matter are conceptions. Hylic and material are conceptions, and when, as Luce Irigaray suggested, something is outside what is being conceived of in terms of hylic and material, it does not have a nonexistence, but it does have absence of existence. In the same sense, it is suggested by bell hooks, and others, that minority or oppressed sexualities and genders are all queer, that is, not normative or explicable in the language and restraints of language on hand.

All it took to ruin the career of the most famous dancer on Earth, in 1918, was to headline one newspaper article, “The Cult of the Clitoris.” We know what “the love that dare not speak its name” is, but we do not really know, yet, about the Cult of the Clitoris.

Fictional people are, much like nonfictional people, conceived by us and not our conception. This is not paradox.

In the long run, all fictional characters are dress dummies the authors and audience put clothes and feelings on. A recurring point of The Invisibles is that in the run of our world, that is what we are. We are mannequins and measurement dummies which fabrics and personalities can be wrapped over. When someone really takes it all of, they take off their they. There is us underneath.

Perhaps mature in his late teens, Jack Frost will say he thinks one of the secret gods of reality would probably, stripped nude, look so much like us you could not tell a difference. Paradox for thought.

Satan, if that is who he is, walks through the comic not so much directly affecting anything, but consistently introducing ideas, or at least, worries. Makes you wonder.

The secret god who will own the conquered Earth, in the end, is eaten by a kid like an afternoon Hot Pocket.

“The Devil’s Daughter,” King Mob calls Ragged Robin, a reference to any woman with red hair.

Kay is born blonde, is blonde in childhood. She dyes her hair, but your dyed hair is yours, is you.

Robin says that by affecting the perspective of historical events, by introducing herself to people in their fictive forms, she feels she is writing pornography. The world may be prose, the realm beyond truth may be thought, but Robin sees her marks on the world as perversity.

“Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure.” Maybe. A Marianne Williamson quote.

Elizabeth Sewell wrote, “The scope of enquiry is limited to what goes on inside a mind.”

Who taught us to have guilty minds and does it pause or stop enquiry?

Barbelith could be the spinning stone of a mill which makes everything. Secret stone.

Does Barbelith talk to us, or anyone, or are those words written by Grant Morrison on pages in a comic book?

It is Ragged Robin reaching out. It is Ragged Robin milling logoplasm. Milling Robin running rote. Robin who wrote.

The Invisibles, if it is a world, is this world, and to quote Sewell, again, maybe unfairly, “all the world is paper, and all the seas are ink.”

If anyone human walks through the world in the same ways as the Harlequinade, the King in Yellow and his servants, as Satan, it is Robin. And, Robin brought her porn with her back from the future. Robin literally time travels nude, stripped of everything she cannot take inside of her, and she apparently thought packing some pornography with her seemed very prescient.

Robin is not the only person who walks through the world by orchestrating the emotional aggregates of walk, world, through, and the and who.

Does Robin talk to us, or anyone, and are those words written by Grant Morrison on pages in a comic book?

Pornography, sexual fantasy, like all fantasy, like fanfiction, is corrective. It may be unhealthy, it may be misapprehending, but it corrects a course of thought or ideation. Corrective, not necessarily correct.

Robin’s role inside The Invisibles is detached. Having written herself into a preexisting history, a predetermined story, Robin’s part is to be corrective. She steers perspective. She engages in unlikely sexual escapades and maintains a mysterious, manic pixie dream girl self-congratulations while self-actuating herself.

Being inside The Invisibles, Robin’s role is entwined. All the curls and cues of her frustrating-to-draw hair.

Since that pornography saves her friends and spares a fallen angel confused by this material and imaginal world, maybe she was right. Maybe it kept her company on bored nights, too. Who is to say?

NEXT: How Did Helga Get in Here?

And previously:

- Prologue/Series Bible

- Chapter One: I Was a Librarian’s Assistant (Pt. 1)

- Chapter Two: I Was a Librarian’s Assistant (Pt. 2)

*******

Nothing in There is Nothing Left to Say (On The Invisibles) is guaranteed factually correct, in part or in toto, nor aroused or recommended as ethically or metaphysically sound, and the same is true of the following recommendations we hope will nonetheless be illuminating to you, our most discriminating audience.

Morrison, Grant. The Invisibles. Jill Thompson, Chris Weston, et al. DC Comics. 1994-2000.

To the Devil a Daughter. Directed by Peter Sykes. Adapted by Chris Wickering, et al, from the novel by Dennis Wheatley.

Keel, John. Operation Trojan Horse. 1970.

Pollack, Rachel. Doom Patrol by Rachel Pollack Omnibus. Medley, Linda and Ted McKeever, et al. Collected, 2022.