Patricia Highsmash

Us Living in Fictional Cosmogonies

Part XIV: Shoujo Kakumei Utena: To Be Both

by Travis Hedge Coke

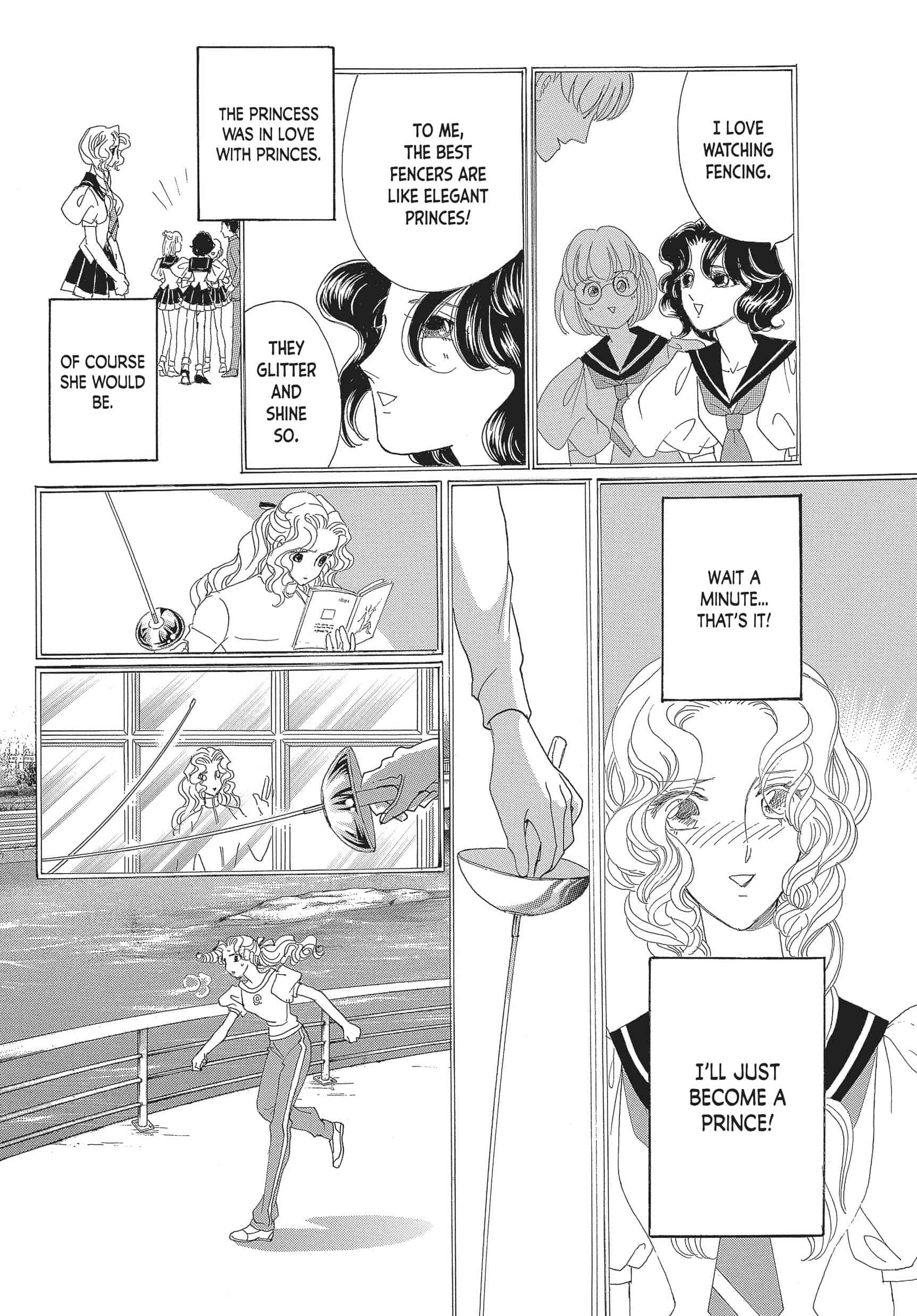

Dead. Not-dead. Prince. Not-prince.

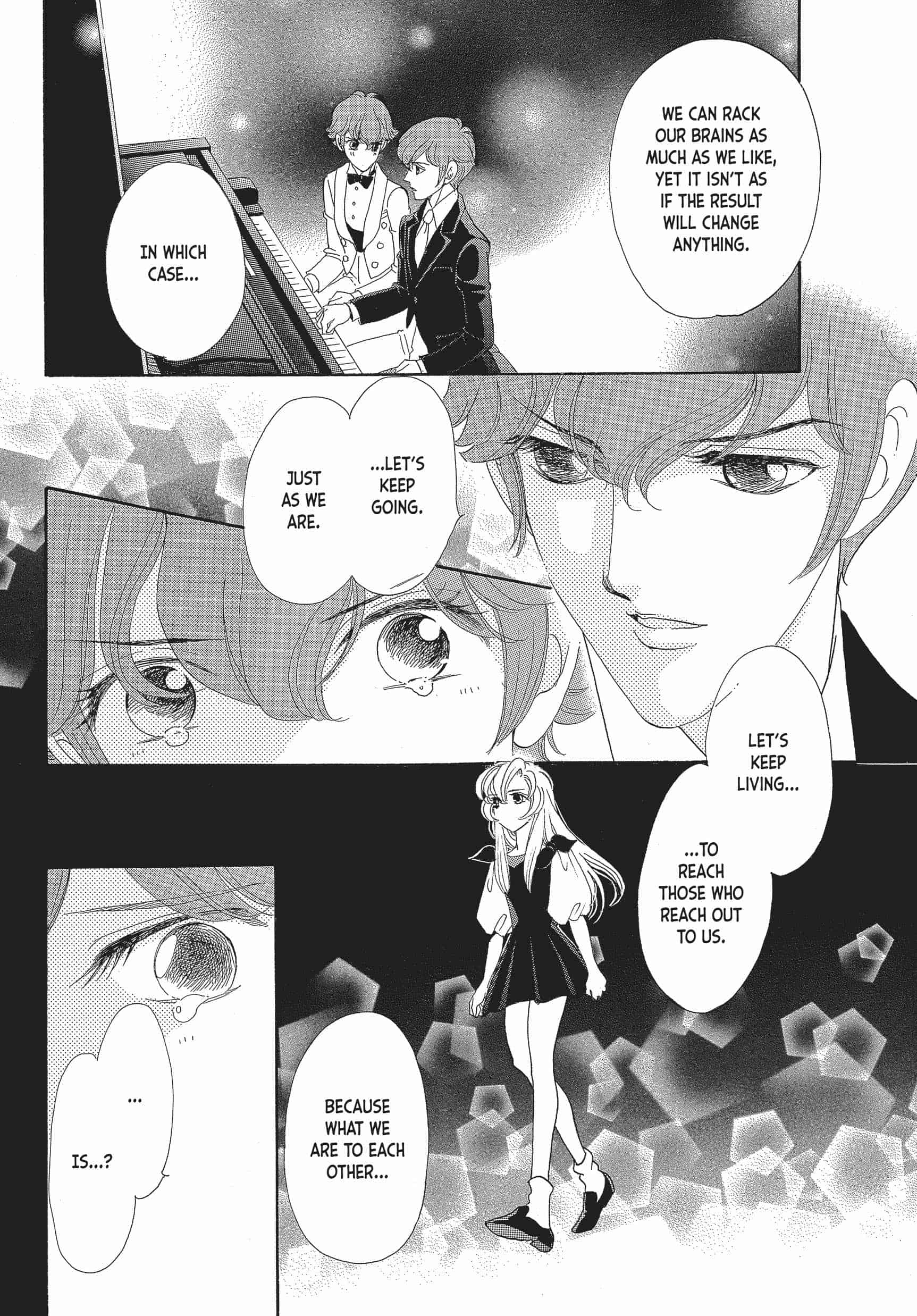

Halfway into the Shoujo Kakumei Utena anime and again half through the recent trilogy of stage musicals (of which two are complete and had their first runs), Utena has to accept that she has a responsibility when she prods or pushes those she has power over to doing her will. She wants Anthy to act a certain way, and while she has power – or a level of affected control – over Anthy, she capitulates to this. In the same way, those who have power over Utena have a responsibility, even a culpability, for how they treat and direct her. This includes Anthy, who has far more – and far more insidious – control over Utena, because while Utena is a well-meaning teenager, Anthy is an ageless or liminally-aged ancient witch, suspended in an adolescent mindset by shame, trauma, fear, abuse and bad habit.

We learn young.

Much of all tellings of Utena – and they are tellings and retellings, evocations of a true story we may never apprehend – the musicals, the television program, theatrical movie, manga and standalone art pieces, all center around shame and the way in which shame structures our self-identities, the identities we show publicly, and even our pride.

Pride is the permitted self-worth of the horrifically ashamed.

Self-worth of the more positive kinds is also found in and around all productions, all tellings of Utena, from Be-Papas’ indulgence of their mutual but idiosyncratic loves of musical theatre to the actor playing Anthy in the musical theatre revivals acknowledging with gratitude that it was her first time, as a darker-skin woman, to play a character who is by design dark-skin.

When we talk about this world of Shoujo Kakumei Utena being a reflection of another or a world being an escape from another, what we generally do, is to pare down the world. But, in daily life, in our own world, the ostensibly really real world, we do the same. We pare it down. Not necessarily simplifying, but parceling. We take a focus.

Even the ways we describe what we do, how we do, shapes what we think we have done. We give a fictional cosmogony to us. To this.

When I write, here, about this, Utena or Shiori or someone else from Utena cannot know what I mean, because they have no genuine autonomy. But, I know Utena, I know Shiori. Boy howdy, do I know Shiori. And, I can decide what they understand about what I wrote without having to deliberately think it out. I am not solving a mathematical formula, I am sight-reading. I sight read almost all text I see, signs, labels, every billboard or poster in a movie’s shot, I read it and I read it again immediately, and it is never because I think text is amazing or magic or better than something else. I read everything twice as fast as I can because I am dyslexic and because my vision is getting worse and between those two things, I am probably more terrified than I know.

Which, is a narrativizing lie. I say, “more than I know,” but I know. It terrifies me. I correct misspelled social media posts seconds after I post them, except Twitter which will not let you. I live in gratitude to editors who fix everything, who will fix the errors in this chapter and the rest of Us Living in Fictional Cosmogonies.

Me writing vs me editing my writing.

When I edit, I guarantee you I read what I am editing more times, and more carefully, than anyone else involved. I have to.

Life is that kind of attentiveness to what worries you and life is lying about it.

Every one of us is more perceptive than we let on, because life, as it is lived, teaches us not to admit it. Don’t give them an opening. Right?

The most recent tellings of Utena, in comics and musical theatre form, have been – of course – heavily influenced by earlier tellings and retellings, but distinctly healthier. In the initial versions of Utena, the original manga and anime, homosocial relationship are inherently predatory or they are romance that is not romance because the characters are closeted or the narratives will not approach a clarification. Saito Chiho infamously voiced concern about making the Anthy/Utena romantic relationship clear, and her manga was published in a magazine with greater constraints on it, in that respect, but also, there are no other healthy friendships between girls.

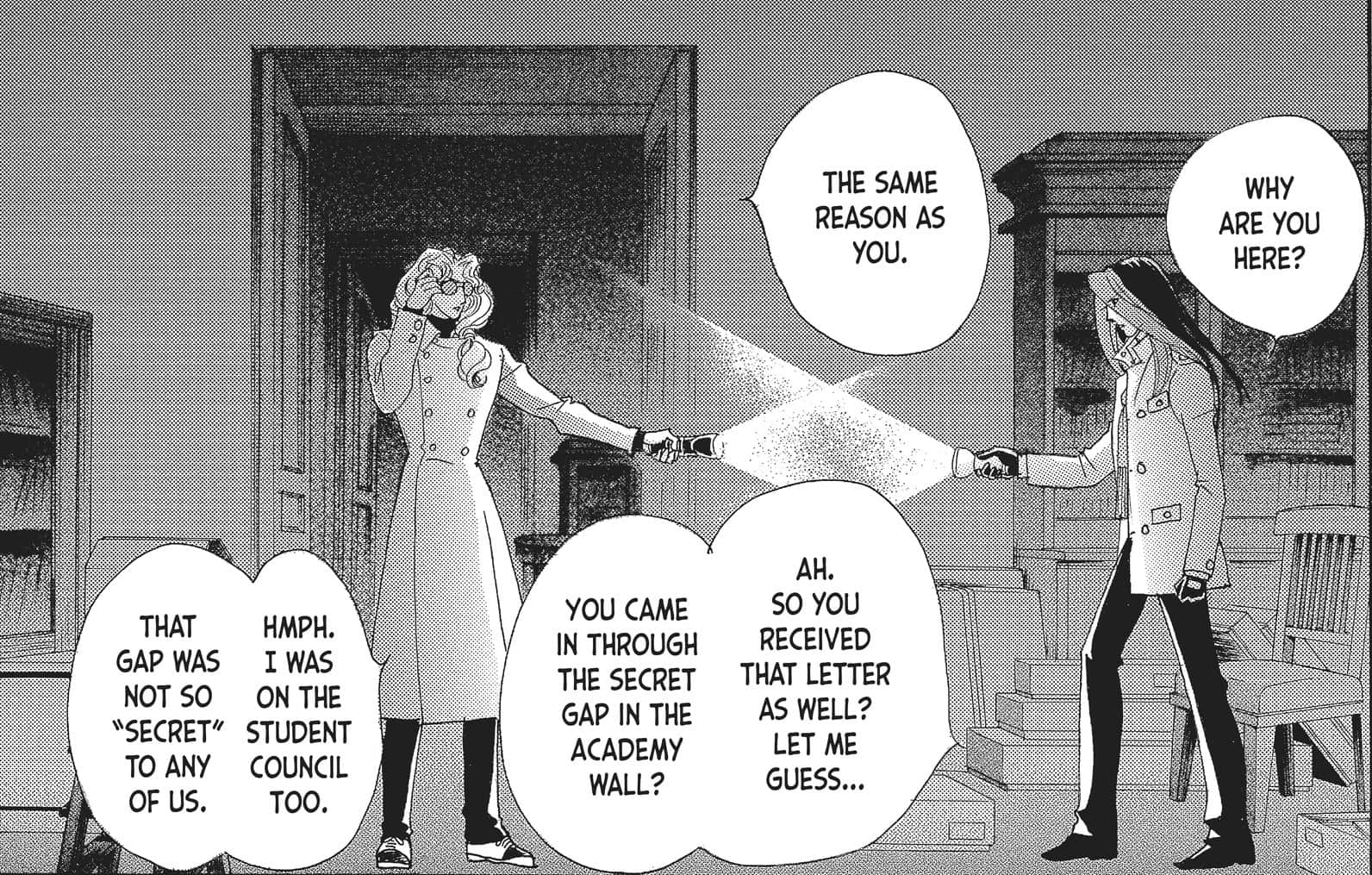

In the 2018 and 2019 musicals written by Yoshitani Kotaro, changes the dynamic of Utena’s earlier girlfriend and friend, Wakaba, and her current friend and coded-girlfriend, Anthy, which in the 1997 anime is purely and really genuinely cruelly antagonistic. Through incredibly similar scenes and an emphasis on a shared enjoyment of food and drinks, they are able to become friends. To be friendly.

The character of Kozue is pulled away from being quite as internal as she is in other versions, and the expressiveness, while it serves a stage performance much better, is also more open and feels genuine, feels like she is a person more than a reflection or refraction of her brother, who in the earlier tellings has always had more initiative and focus.

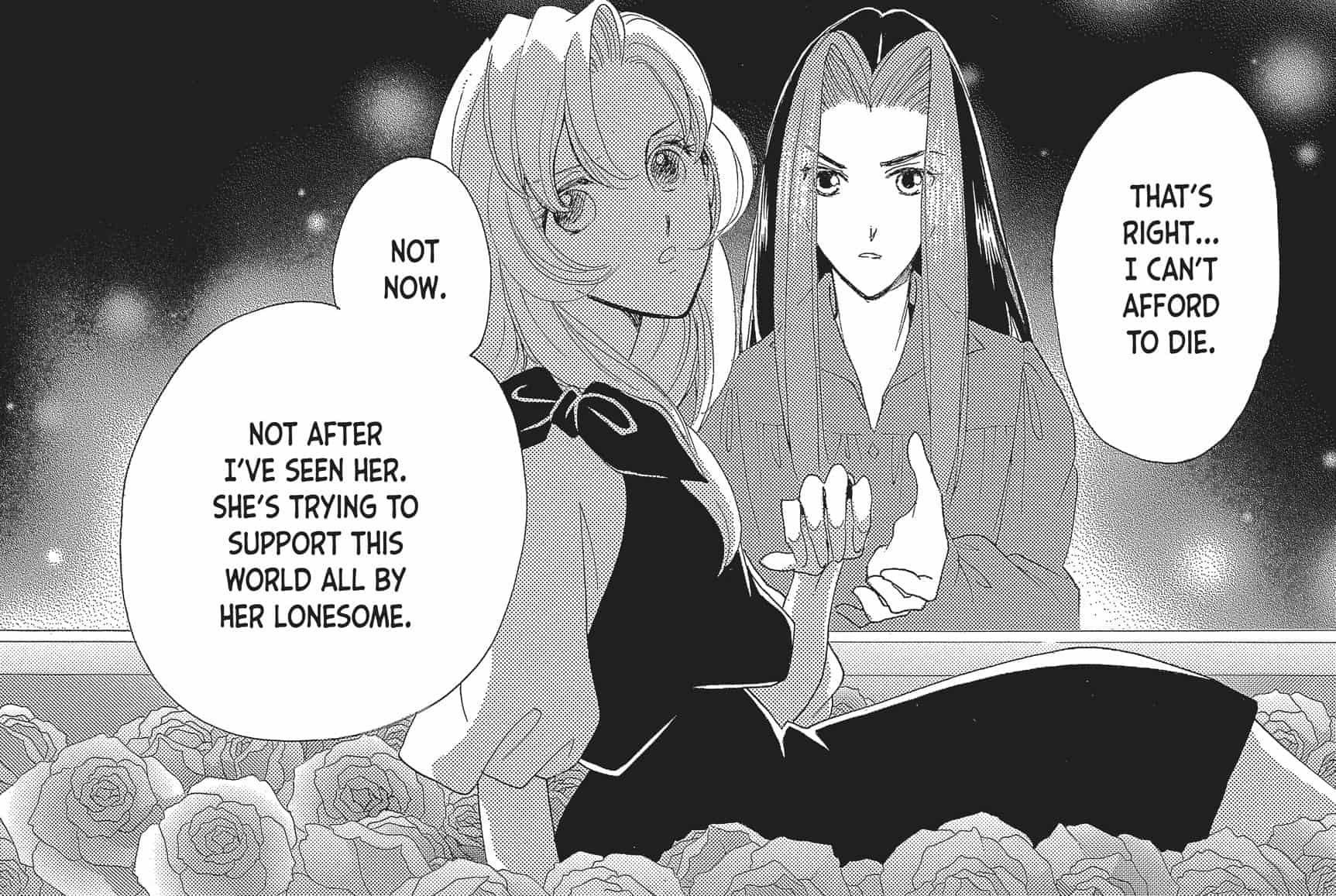

Saito’s anniversary manga, set years after every other version of the narrative, After the Revolution, takes a method from the theatrical movie, The Adolescence of Utena, and presents the familiar characters almost inverted from their earlier portrayal, or what we understood of their portrayal. Adolescence seems to take some of that note from the Twin Peaks theatrical movie, Fire Walk With Me, which similarly presented characters we all felt we knew, but in a way that showed us part of them that felt opposite, even felt opposed to what we knew. One of the actors from Twin Peaks flat refused to do a scene in that film because it was too opposite his understanding of his character.

There is an acting technique often utilized by Martin Landau, which hinges on the idea that people do not do, so much, what they want, they do things to avoid or cover up what they do not want. When he played Bela Lugosi in Ed Wood, he handled the accent by playing a man who does not want to have his accent. He has his accent and he is trying not to. In the X-Files movie, Fight the Future, Landau’s character exhibits traits of bravery and hubris because he does not have that. He is affecting bravery, affecting hubris and confidence.

Characters in Utena, like Saionji, Juri, or Utena affect a maturity they do not have, and characters respond to the affectation. A savvy character, like the manipulatory demigods, Anthy and Akio, can see through the pretend adultness, but some adults are fooled; many of their classmates are fooled. Sometimes, they fool themselves.

Any time we’re looking at someone else, we’re looking in a mirror.

When we see Saionji and Juri again in After the Revolution, their adolescent immaturities and their adolescent weaknesses feel more resonant, more pronounced, but only because they have aged and have not grown out of them. They grew into them. They have not yet understood that there is revolution for them as well as for special someones.

The probably healthiest shift between the most recent tellings and the earliest, is that “shoujo kakumei” is no longer rendered only as “revolutionary girl,” which has always emphasized Utena as the revolutionary, the one for whom there is a revolution (with Anthy’s following hers or being concurrent but following the spirit of Utena’s). The phrase can now also be rendered, in English, as “girls revolution.” Not one girl; all, any girls’.

After the Revolution makes it apparent that this applies, as well, to other genders. Everyone or anyone can have or experience a revolution, a miracle. We had seen this all along, but even if we understood what we were seeing, what we were understanding and taking in, to voice the understanding was probably too threatening. The manga voiced it, so that we, also, can take the risk. Now we are bolstered. We are supported.