“This comic only took two minutes to read,” would possibly concern me more, if it was not inevitably also part of a conversation on how the two-minute reader missed something vital.

Patricia Highsmash

Stop Worrying How Fast It Reads

by Travis Hedge Coke

Do the words make the scene longer? More meaningful? Do they reassure us of what we can largely see?

Saito Tamaki has suggested the anxiety of reading speed (or, more accurately, reading delay) being associated with, “more bang for your buck,” is an American, or anglophone issue, more than anything endemic to comics readers or, simply, modern audiences. Dr Saito notes that Japanese, and many other audiences, do not suffer a similar anxiety to the same degree. There is a grammar of movement, similar to Gilles Deleuze’s movement image and time image breakdown of film/audiovisual communication, a codified range of signs, symbols, and cues for reading a comic and for knowing how we are expected to pace progress in a comics’ narrative, both the time allotted to reading a page or sequence in print, and the time acknowledged within a panel, scene, or story.

On a basic level, anglophone narrative media is by default three-act narrative. The strip, often, has three panels to execute each act almost too clearly, with an unacknowledged atemporal act in the title panel preceding the narrative comic. The serial issue, if a story extends the entire length, or bulk of the length of the issue, is restrained by a prescribed page count, by the placement of ads, which sometimes interfere with the narrative flow, and by the nature of printing, which requires a reveal to either lie on the righthand page, where it is visible while we read the lefthand, but perhaps not parsable, or on the left, to be read as soon as we have turned a page. A two-page spread requires two uninterrupted facing pages.

While these restraints, or if you prefer, accommodations, may seem simple and unaffecting, a simple miscalculation or disregard of page count can result in one or several spreads being interrupted, broken in two, with the second half printed on the reverse of the first. This can generate some interesting results, and the rise of tablet-readers have led some artists to designing them for the split, with elements balanced to read as a two-page spread or two distinct full page illustrations. Recent Jim Lee spreads allow for the tablet-split. Some Tony Daniels art gains some stylization and some narrative drive by placing a starting point on the left side and a burgeoning narrative motion on the right.

“Writing for the trade” – met with anxiety at its inception, and somewhat still – is a necessary acknowledgment that the greater readership for and the greater income from a comic is, in the 21st Century, in so-called bookshelf editions, in collections/reprints with a higher page count than your average monthly serial.

I think we can even go back to Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, and see that there is a generation or two of anglophone comics readers, especially American readers, who were trained to anticipate both reading time and content quality in terms of motion-to-motion panel progression. Scenes of stargazing, park-sitting, bicycling, internal thought or feeling, are treated as filler or deliberate time/effort-wasting on the part of the writers and artists, unless they are also slathered with narration or dialogue. A scene where a character goes through a series of emotions, or a scene which suspends a moment for both character and reader to indulge in a tone, are not lacking in content or intent, and scenes of punch punch run kick, or talk talk talk, in any fashion more filled with content and resonance, except inasmuch as a specific reader may only glean significant content and relevance from the latter.

Gekiga Time, a field of information from all places at once.

Cinematic Time, flowing left-right across the top of the cover.

Comics, by their nature, are not reality, but neither are they very often photorealist or even realist. Alex Ross comics, while often marketed at and celebrated as realist, tend to be genre work, codified and restrained to somewhat unreal social presentations, even if we disregard the irreality of the blatantly fantastic elements. Nothing wrong with that, but it is not realism. Alex Ross comics, perhaps to a one, are naturalist comics. They trade in the language and achievements of naturalism. They feel realistic, but never threateningly or grotesquely so.

Again, what we are trained, as comics readers, to perceive as valuable content, are that those genre markers are not transgressed upon or threatened, and that detail never step over into the gross or unavoidable. Ross’ restraint is admirable and part of his talent.

Dr Saito breaks down manga time image by, cinematic time and gekiga time, and it is gekiga time that, I think, that most distresses American audiences, though on more cynical days, I wonder if American comics-reading audiences have as much tolerance for time spent in the frame of cinematic time in terms of a comic, as they would with a movie or television show.

I am being precise and academic in terminology, because these are things worth discussing precisely, with care and considered thought. They are circumstances most audiences never recognize are occurring as they read, or even when they think back on a comic they had read. They are circumstances, which I believe most creative people in comics do not necessarily realize they are dealing with as they create, much of it either being reflexive, intuitive, or simply understood.

Motion image, time image, gekiga time, et cetera, are fuzzy terms, even as they are precise. They are not concrete and bordered concepts, because they deal with a range of perceptions that are idiosyncratic to every potential audience member, and only pick up their beginnings of concretization when a sufficient pool of audience members are taken as a whole.

Motion image, in film, is the actual moving image onscreen, the colors, lights, darks, the cuts and angles, distortions, filters, fx, and the accompanying naturalist soundtrack. As audiences, we hardly notice any of these elements or the existence of the motion image. What we perceive is a mild-hallucinatory form of the time image. Time image, is the duration we feel has occurred, with some stop-the-bomb sequences contracting to a shorter time duration, perhaps, and some montages, like a scene wherein a character changes clothes several times, selecting the perfect outfit, or a war is shown contracted from several months narrative-time to a few quick shots. Months can be felt in the time image of seventy seconds of motion image.

Comics have no motion, traditionally, so when we deal with time and the basic grammar of time in a comic, we have the page time, the reading time, and the distortional cinematic and gekiga times. It is suggested that some comics trade in cinematic time, some in gekiga, but in truth, all comics are subject to both, and only sometimes is either one consciously evoked or refined by the authors/talent making the physical comic.

Gekiga Time

Cinematic time borrows codification and audience-expectation from cinematic visual language, but unlike cinematic image/time-sense, the panels in a scene represent “time [flowing]… at a mostly consistent speed… [maintaining] the objectivity or intersubjectivity of time” (Saito Tamaki, Beautiful Fighting Girl). Gekiga time, is world-time turned subjective, almost animist. “Time no longer flows. It contracts and expands along with… subjective viewpoint.”

Cinematic Time

Cinematic time, then, is what pervasive and subtle cinematic editing – which moves too quickly for us to follow, as an audience, too critically, compared to the static page of panels of a comic – and becomes natural enough to feel very real, even more real than real.

Dr Saito says, in the mid-90s, “[E]ven cutting edge American comics are often slow-paced comics with Japanese.” He says this after pointing out that a best-selling Japanese comic once spent three years serializing a single baseball game in detail and gekiga time. It is because of the American general antipathy to gekiga time, to subjective time dilations or contraction. “They use chronological time in every respect… emotional prolongation and exaggeration is minimized,” and character perspectives are relegated to monologues, soliloquy, and narration.

Cinematic Time

We are trained, by exposure and repetition, to this time-flow and these expectations.

Gekiga Time

When, in the States, we discuss or rank the best comics of all time, the comics where characters narrate themselves, even sometimes in the most prosaic or repetitive blocks, generally rank the highest. We like to be told more than to feel, to be told more than to experience.

Cinematic Time

Except that is not true. It is not necessarily even half-true. Comics by or for a female readership have always, in American publishing, and to an extreme degree in British comics publishing, utilized subjective time distortion openly and successfully. A Misty serial could stretch a day or two for a year of releases. Teenage dating life comics, young women with jobs comics, the atemporal comedy comics, everything from Betty’s Diary and Archie’s Pal, Jughead, to Little Lotta and Richie Rich exist in a gekiga time framework. Most daily/weekly newspaper strips trade heavier in gekiga time than cinematic. And, what unifies Archie books, newspaper gag strips, and comics where Patsy, Millie, Barbie, or Little Dot take on new vocations and ventures story to story, is that they are written off as frivolity and disregarded as art or popular art no matter what the sales or impact on their audiences by the sort of critic or historian, pro or armchair, who default-laud the cinematic-time-emphasizing comic wherein very serious men narrate their every step.

There may have been a better way to walk you around to an illustration of how neurotic we get, as a group, about non-cinematic time and comics that read too fast, or too slow, that do not use words when they can use images, that do not narrate emotions but illustrate them, but that above is just some of how goddamn neurotic we can get.

Gekiga Time

In a similar vein, comics by non-anglo artists and writers working in the anglophone markets, have similarly worked directly with gekiga time on more open levels, and with “emotional prolongation and exaggeration,” exemplified in American Born Chinese or This One Summer, and also injected these formal considerations and techniques into traditionalist comics heavy on, and thick with cinematic time expectations. The attention to detail from South American artists, the labyrinthine line work of some Filipino artists, the expressive and almost squirming lines of Croatian pencilers on X-Men and Batman comics, have had a dilatory effect on how they are read, even when paired with traditional action to action scripts.

We get so caught up, we ignore that Matt Baker was making bookshelf original graphic novels in 1950. And, then it becomes erased from the record and memory, and from recitation.

I am not suggesting a purely cultural, and definitely not a genetic or hormonal cause for the embracing or avoidance of non-cinematic time, of kairological or chronological time-sense. Matt Baker did Rhymes With Lust for the bookstore audience with white writers. Larry Hama and Trina Robbins suspend, extend, contract, and make rollercoasters and tilt-a-whirls of narrative time because they are strong creative forces and know what they are doing. Go Nagai and Hiromi Takashima do not present time subjectively and arrest their most arresting moments because of a national identity. But, in large enough sample sizes, the audiences that respond strongest, most positively to these techniques, to these expectations, do show trends.

“This comic only took two minutes to read,” I said above, would possibly concern me more, if it was not inevitably also part of a conversation on how the two-minute reader missed something vital. How many of you assumed I meant something like a line of dialogue or physical presence that would affect the narrative? We tend to treat narrative details and contexts as clues, because we are trained to that cinematic time ideology. Chronological, causal time sense.

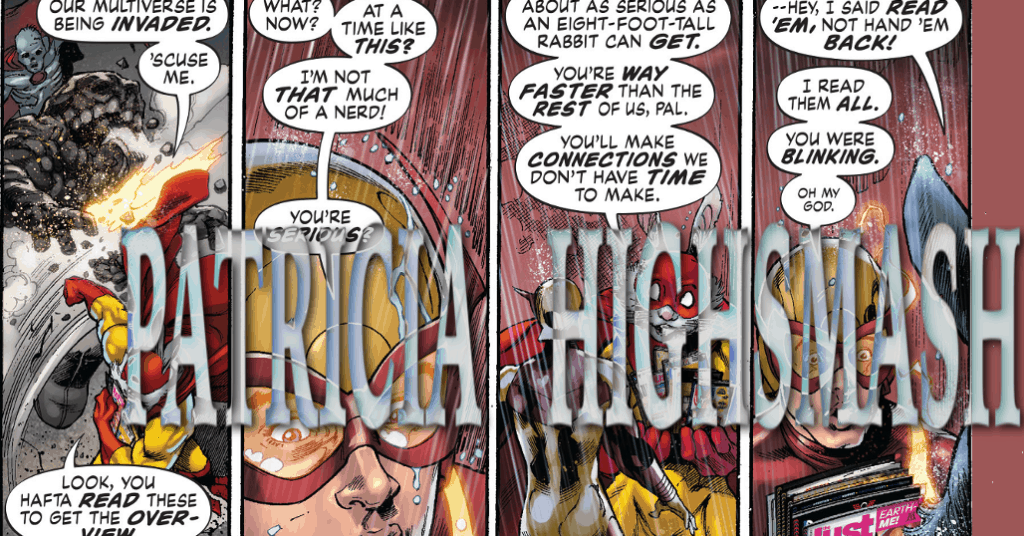

A “cinematic” page of gekiga time…

An emotive example of cinematic time…

Culminates in deployment of both at once.

The standard American comics readership strongly leans into asking why Character X would lie, meanly, to Character Y, when the most obvious answer is that they’re very very mad, or very very jealous, or very very very very upset. That general(ized) audience does not like upset to be a valid motive. They have to have a plan, and a plan must be a sequence of steps. The reduction of the kairological back to chronological. To not enjoy one or the other, in entertainment, might be only a small thing. But, to not know why one or the other agitates or causes real anxiety rolls out across our entire lives and our subcultures and cultures. It is to be ignorant of ourselves and neighbors.

A comic cannot “take only two minutes to read.” You choose who long you spend actively looking and parsing, or processing after looking. You choose to take thirty or “only take two minutes to read.” You choose what you are willing to miss.