There Is Nothing Left to Say On The Invisibles

3.11

Style/Flubs

by Travis Hedge Coke

One of my bizarrely clear memories of an otherwise blurred trip to New York City to visit an aunt, was a pop musician saying she was beginning to be comfortable in her own clothes, a play on “in your own skin,” and how much reading it offended my aunt. She could not decide if she believed they made a mistake, simply said the phrase wrong, or if they were changing it intentionally, which it seemed would equally offend.

“He was black in the face, and they scarcely could trace,” says the fourth stanza from the end of a fit in Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark, continuing:

“The least likeness to what he had been:

While so great was his fright that his waistcoat turned white—

A wonderful thing to be seen!”

Colleen Browning. Daylight Goyave.

In Goyave Night Scene, Quincy Troupe writes, after a “black & white photo” and a “black & white couch,” of “the leonine ‘prince of darkness’ dressed in black lizard pants, open white shirt,” his black scare, his tough, his black panther slouch.”

Though, “all is not paradise here,” Troupe says, it may be, “close as anything beautiful can be to the paradox of mystery, surprise, wonder”.

A recent wave of suppositions, online and elsewhere, that Anne Frank has “white privilege” and that Frida Kahlo was “white mestiza,” have brought back this memory with clarity. One tweet I saw virtually gasped, “Did you know [Kahlo] borrowed a dress from a maid!” Under both sets of disinformation, people asked why they or their children were never taught these truths in school.

Troupe writes, in Goyave, of Miles Davis, a man, who along with his looks, his drag, his performances, his being, as a being, Troupe has covered and replayed like the best of songs, the best repertoire.

The only thing more copied that a Frida Kahlo is a Frida Kahlo.

“You do not do, you do not do

Any more, black shoe

In which I have lived like a foot

For thirty years, poor and white,” opens Sylvia Path’s Daddy.

So much of life is not only getting comfortable or being made to be uncomfortable in our own skins, but whether or not we can find comfort in our clothes. Between dressing for success, dressing to just not be killed, and dressing for our private at-home selves, more of our lives and identity are the underwear we do or do not wear than we commonly reckon with. The style of boot communicates something of us, the style of skirt or jeans or necktie, but the style of sock we don is more often specifically for us.

A good amount of time, we get comfortable in someone else’s makeup, someone else’s lizard trousers.

It was on that same trip to New York, that my aunt’s spouse at the time, an espoused vegetarian with no time for corporate entertainment and capitalist art, took me to get “the best burger in the neighborhood,” one of which she also devoured, and to the Broadway musical, Urinetown. Whoever played the urine police, it was the first time I think I understood how someone could look “smart in their uniform.” They posed and hammed and winked the way real life too cool cops sometimes will, the swagger of freedom to commit violence, which I had seen in life but I do not think I had seen before on stage. Stage lighting gives the staged poses a veneer.

As someone who can no longer walk a mile in anyone’s shoe, who can barely stand on both feet, I ask:

What is it with costuming that we respond to so viscerally even knowing it is dress up and fake? We do respond dramatically, with an incisive fraudulence of our own. This person is a bigot, this person an authority, this person weak or strong or saintly or soiled because of their coat, their shoes, their hat, their badge. Even when we know they are playing make believe.

When Ragged Robin dresses increasingly from the same stores as King Mob, she in effect takes on the best parts of him. She embodies his coolness, because his coolness is fairly coat-deep. It is as close to his bones as tight leather trousers. But, look at the difference between Mob from year to year.

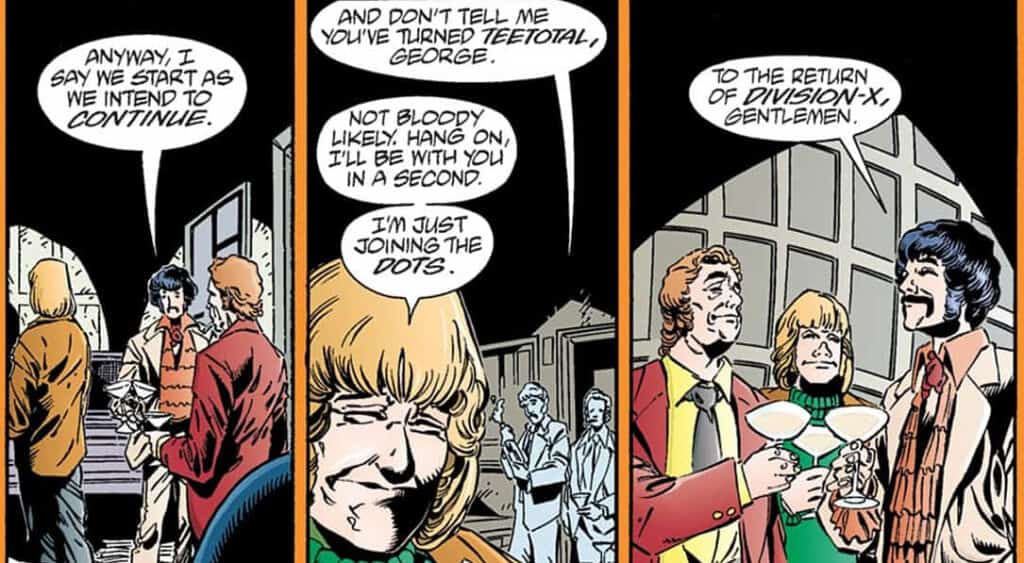

Division X is a cosplay troupe.

The Invisibles Volume Two, their trek back and forth around the United States, is a superhero finding yourself roadtrip. If Volume One is The Chronicles of Narnia, Volume Two is To Wong Fu, Thanks for Everything, Julie Newmar. Which is a good reminder that literature, film, and comics all have their children’s, adult, and all-ages ranges, and those ranges are largely internal to each of us or simply a note where to shelf the copies you have.

Mentat, mein todt. If this is in relation to Dune and things riffing on Dune, we have a clear, if complex meaning. Room to wiggle. But, we need to understand (only a little) Dune and to understand (only a little) German. If it is nothing to do with Dune and “mentat,” is a Catalan word, why is half the sentence in Catalan, half in German?

Affectation is not a bad thing. We all have to wear some clothes, some of the time.

It is always funny to me, when people complain of Lord Fanny traveling the United States with all her wigs and no noticeable luggage, as is no one else changes clothes, they do not have hotel rooms consistently, and the very idea that King Mob has the magick secrets of teleportation but Fanny probably would never.

We often like to dress up, and we sometimes dress down.

In Volume One’s She-Man arc, as a young one-day-to-be-Fanny, Hilde, perceives the world made flat, facades and cutout shapes, Hilde, of course, is flat shapes, facades on a page or a screen, those transfigured by light and hope, fear and love, into something rounder and more flexible inside our heads, in our lives. One-day-to-be-Fanny is Lord Fanny is one-day-to-be-Fanny, interlinked across panels, over pages, in planes and in pains and on panes. The roar of time increasing in speed and hustle around Lord Fanny is akin to trestling under no influence, a smooth, open streamline of the exposed tracks and trains of a ghost truth behind our facades, the train cars rustling and vibrating a thunderous song deeper than our bones, shaking us under our cores, and then one day you snap to and realize your weight ballooned overnight, your wig is not on straight, or you need to paint your nails again.

In 1971, Traffic recorded,

If you had just a minute to breathe

And they granted you one final wish

Would you ask for something like another chance

Or something sim’lar as this

on their song, The Low Spark Of High-Heeled Boys, about Michael J Pollard, whom Jim Lowe had made the 1968 song, Michael J Pollard for President, about. I think of Pollard as someone missing from The Invisibles, especially Volume Two’s course ‘cross ‘Merica, his character from an episode of Gunsmoke, where he was a deceptive, but believable murderer, an actor who could turn the glint in his eye to any truth, who held all conviction in his unassuming assumptiveness.

What drives a singer who cut singles of The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere, Man of the Cloth, and Hootenanny Granny to arrange the gleefully psychedelic, pugnaciously glib hipster track like, Michael J Pollard for President? Jim Lowe, doing The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere, is doing an act. Michael J Pollard in Gunsmoke, in House of 1, 000 Corpses, as a presidential candidate in a song, is an act. Walking down the street or cruising the boulevard is an act.

“While you’re living beyond all your means, and the man in the suit has just bought a new car” (The Low Spark Of High-Heeled Boys) is an act.

What I mean is some things become so endemic they populate in your head or your head populates them for you. To be truly not under the influence, you would probably have to be on something. The flashbacks, the derails, the high rails, the High Sierra, the Pine Barrens with their witchy devils and weird towns, the Texas Vampire Movie a tough guy sometimes walks into one morning trying to have cornflakes and coffee and punk out the queers at table four.

The way we talk is another set of clothes. We have to talk we talk in our own privacy and we have the talk we talk when we dress it up for public. And if the world is a movie set, gammon set, they are all affected. Even the sets of dialogue, the nostalgic accents we have worn into grooves all our own. Most actors, at some point, find they can no longer speak readily or reflexively in their own accent, a dialect of youth or ethnic origination. To become is to not just be or come. There is a trick in it.

Do you want to hear the good news? America is a movie set. Since lantern shows.

Berth before conception.

The movie is a movie set. And if the world is a movie set, game and set, it means we can dress up and try out for roles and if we have a bit part, we can spice it up and if the director or a producer does not catch us and stop us, it makes it in the cut and there it is.

*******

Nothing in There is Nothing Left to Say (On The Invisibles) is guaranteed factually correct, in part or in toto, nor aroused or recommended as ethically or metaphysically sound, and the same is true of the following recommendations we hope will nonetheless be illuminating to you, our most discriminating audience.

The Low Spark Of High-Heeled Boys. Traffic. 1971. Tracks 6 through 1, descending, then 7.

The History of Underclothes. C Willett and Phillis Cunnington. Chapters 13 through 1, descending, then Introduction, Bibliography, Appendix, and Index, as needed, but not afore.

Black Cherry. Goldfrapp. 2003. Tracks 9 through 1, descending, then track 10.

Something Else By the Kinks. The Kinks. 1967. Mix or take in combination as needed.