There Is Nothing Left to Say On The Invisibles

3.07

Take People As They Come

by Travis Hedge Coke

“Try to remember,” says the text in an issue of The Invisibles, “it’s only a game.”

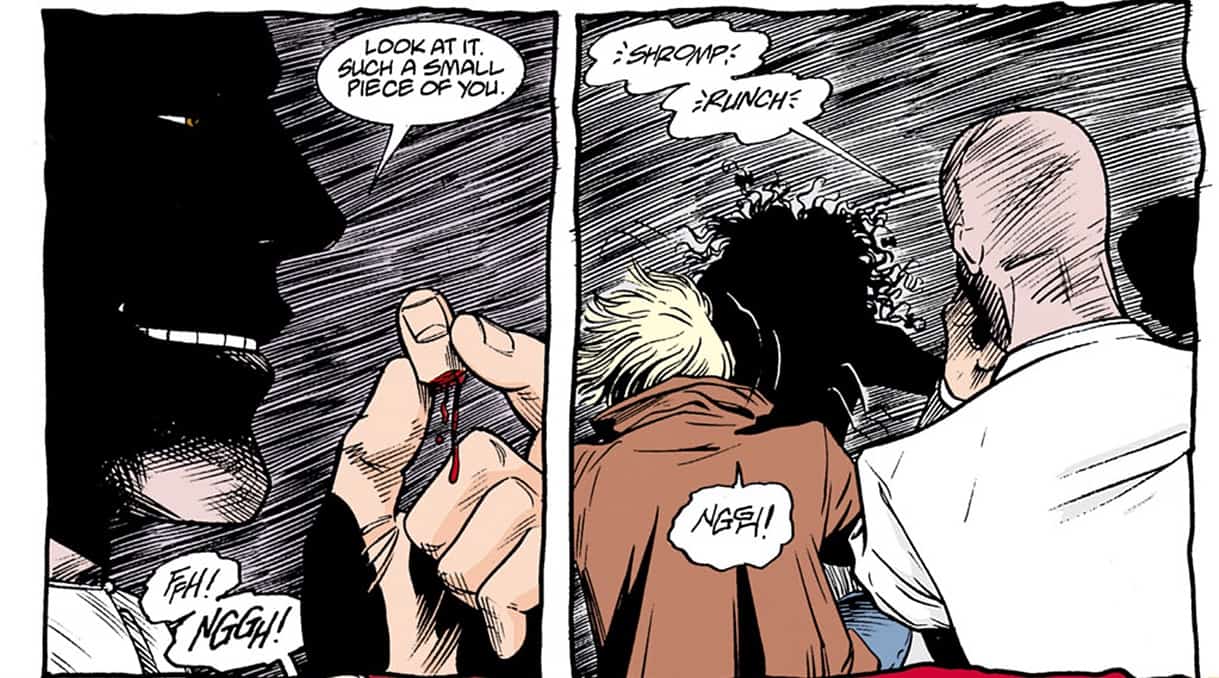

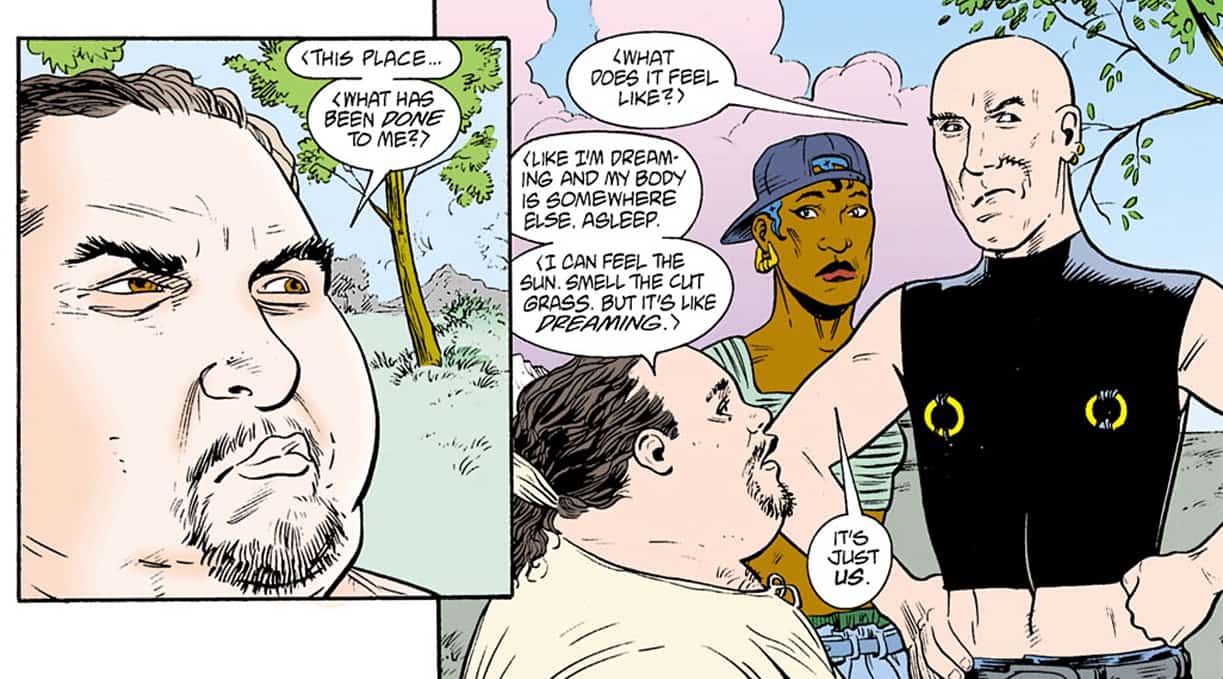

They show us Bobby Murray. Bobby bastard Murray. Rotten man. Common soldier. Wounded warrior. Golden-haired asshole. Prison guard. Beats his wife.

Try to remember that it is only a game.

They show us no determinedly-gendered transgender people. Only determinedly-gendered cisgender people and nonbinary transgender people.

And, tell us to try to remember, “it’s only a game.”

Our tendency to forgive, rationalize, and relativize fictional people is matched too well by our willingness to do so for real nonfictional people, provided they also tick off enough of the right boxes on the list in the right moment.

Jack Frost and other luminaries of The Invisibles tend to believe both an innate goodness to people – that we should keep fighting to make friends with everybody – and to a moral relativism by way of acknowledging everything in the universe is as it should be.

It is as was for me and you to default to strategies, when we can apply tactics. It is easy to think of theories which do not apply to everything as applying to none, especially when they do not apply to a set which hold the most default power or the most presence in our thoughts or expectations.

In a society which perceived cisnormative roles as default, as most common, or as most real, and other forms as violation, the violation can be a mark of pride, of strength, identity, resistance, and this has frisson, this sends a shiver through our being, but it leaves a perpetual requirement to resist a thing we have now made, at least socially or psychically, permanent.

Jack Frost believes there is another side even as he rejects other-sidedness. Jack is “on the side with jam on it,” or multiplies the sides to the sides of a piece of string, but in practice this wittiness is an act of resisting a binary he has to keep believing in.

Jack Frost is ready to make friends until the other side beg for help until something is going to make him late for dinner or step on his toes.

Most of us do not begrudge flies, unless the fly is bothering us. And, a fly is not even trying to be mean about it.

We do not settle if Bobby is told to try to remember, if Bobby ever knew it was a game. We do not settle for one puppet master or one puppet play. Pay for pay. We remember. Are reminded. Are reminder. Remember. You.

People, often, are cruel, vindictive, manipulatory, vengeful. Some folks are bad folks.

Do we have to call out? Do we have to say?

It is well and good to say you take people as they come, or to try to do so, but when that modus operandi is to only appraise people’s behavior when it affects you or is directly in your immediate attention, it is not only not worth it as a practice, it actively hurts people.

When hold tongue? Pen? Touch keyboard? Touch grass?

Even as fictional characters in a fictive world, if we frame Sir Miles’ arrangement of child murders, of rapes and kidnappings, assaults and tortures, as morally equative to joyriding, tagging, dispersing satirical flyers, or even King Mob’s violent prison breaks or gunplay, are doing damage. These lines of thought and discussion inspire us to frame real circumstances similarly until war criminals and heroes sit side by side to watch professional sports and pass their candy back and forth.

How much do we have a moral imperative to appraise, judge, condemn and praise real or fictive people? And, the further from our intimacy a real person becomes, how fictionalized might they also become? How do we extinguish the sense of familiarity and intimacy with wholly fictional people, who cannot be known in the way of living acquaintances, but only in artifice and incompleteness necessitated not by their autonomy but their inherent lack of complete form?

It’s a world of homunculi and truck divers.

Shown determinedly-gendered by admission or inference and trans or cis by declaration or inference, we decide. We appraise. We uptear. Uprate.

We cannot call bombings or mass murder, clapbacks, but sometimes we say they are a response.

No matter how you do, you and I are going to fall short of perfect. We know no one enough to make a permanent and evergreen appraisement. Maybe, taking people as they come to us does not have to be a way to excuse hypocrisy or make things easier on our daily conscience.

As adults, we sometimes need to be reminded, as children do, to put on our rain boots, to wear a hat in the cold. Protect your ears. Check your head.

In 1666 it was published by a Duchess that, “Nature is but one Infinite Self-moving Body, which by the vertue of its self-motion, is divided into Infinite parts, which parts being restless, undergo perpetual changes and transmutations by their infinite compositions and divisions,” and (in a message for part four of our journey), “Fire is but a particular Creature.”

We have to remind ourselves to protect, to defend. Maybe we need others to remind us what we are defending or why.

Everybody gets the phrase about good offenses and defenses backwards sometime because it just sounds agreeable. However you say it, especially because there are repeating syllables. If you can spell it, you can make it happen. I tell you three times! (Or more!) Complexio. Symploce. Familiarity. Confirmation bias. Earworms. Earthworms. Little ring. Ring ring ring. Der Ring des Nibelungen. God peeping from the lines.

A dandy in the world dies eating a fish who sat too long in the sun. The heroine in high boots, addicted to skipping steps. The music of the harp. The devil. The rose.

“God wishes to be seen, and he wishes to be sought, and he wishes to be expected, and he wishes to be trusted.” Julian of Norwich.

Before that, Julian wrote, “[I]t is God’s will that we believe that we see him continually, though it seems to us that the sight be only partial.”

You can take everything as it comes, each domino as it lays, but if you play like it lies, the lies become you. Or, the formalism of that sentence construction makes it appear as so.

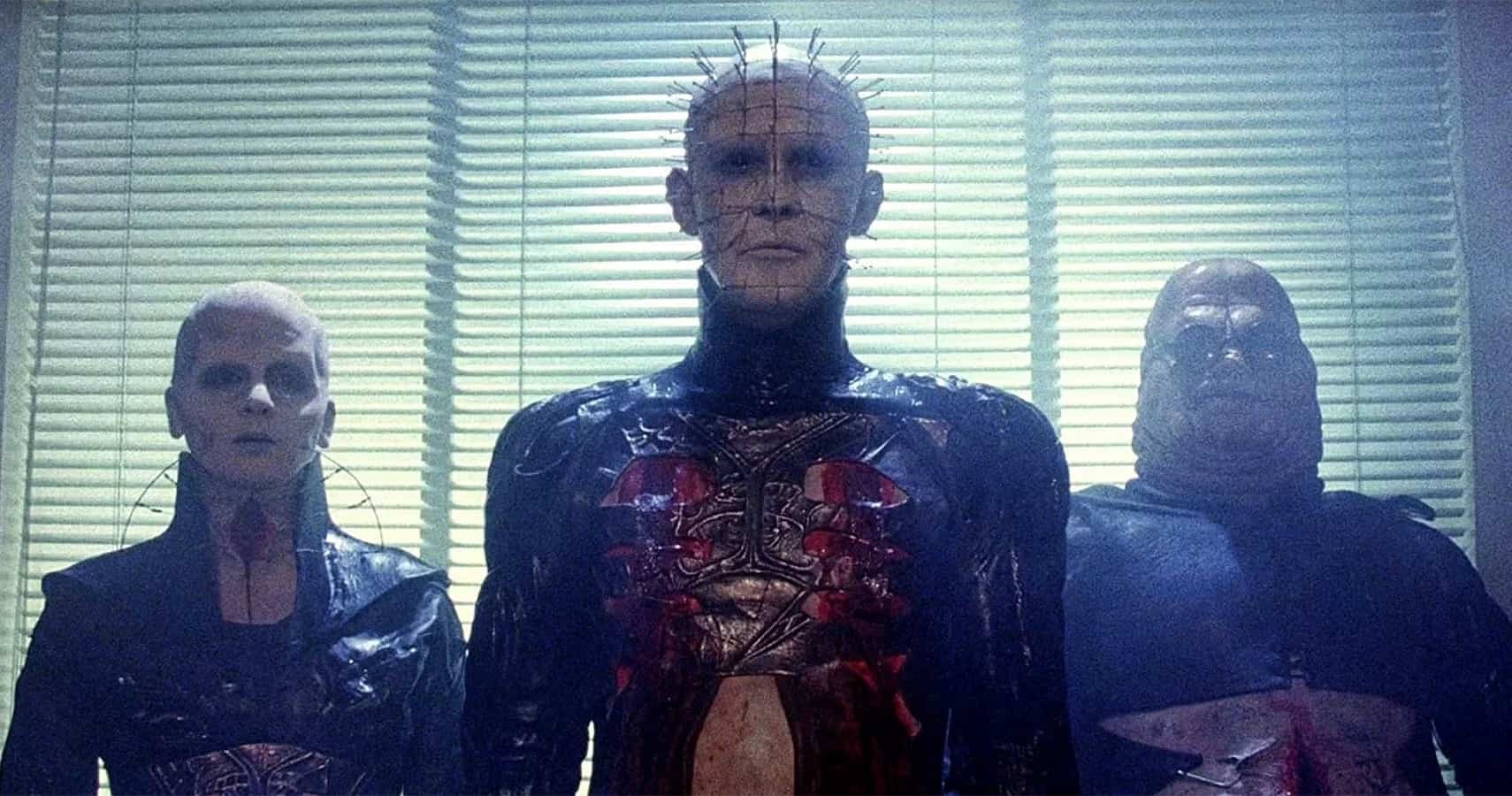

I could take Julian and Sade and consider them both in their cells, isolated, a little lonely and mystic, developing giving bodies and forgiving perversities like unto the pierced-chest wet nurse look of cenobites in a Hellraiser movie.

I could draw three or nine loteria cards and make a guess.

Sometimes, we only have our bodies and the sense of a body, and need to look inward with what we are afforded.

The Marquis De Sade of the 1990s, in The Invisibles, is a living ghost, a collective idea, and the De Sade portrayed as if in the era he lived is a collective ghost. You cannot show a real person in a fictional construct like a story, a portrait, a showing, a telling. We make him.

Emilio, in The Invisibles, is a real guy. I do not even know Emilio’s surname. We make him, too.

Editorial made sure names, including Jerry Springer’s, were redacted from the comic, his black-barred in an issue. We know who they are, or we make them up.

I know Emilio lived with Grant Morrison. I know Jerry Springer is a man from the tv. I have read more from and about the Marquis De Sade than I retain. I know some characters in the comic are based on true life figures, some are combinations of true life figures, some are modeled in part on true life people, by those people or by others. I know it is complicated, and that even fictive people can be complex enough to lose awareness of more of their aspects than have been learned.

We are all really easy to lie to. Especially, those of us who believe we are not.

A construct, like The Invisibles, like card decks and systems novels, implies a randomness and an order, neither of which are complete or omniscient, all of which can seem as if they are. We appraise the dandy. We judge the heroine. We fault the fish or lionize the sun. We keep one eye on our bingo cards even as we listen to the words of the bingo announcer or the mumbled rumor-spill of our bingo-playing neighbor, sat beside us in a hall or a room or in our imagination as you and I visualize my fictive example.

You’ll start seeing the harlequinade anywhere.

How condemnable a person is depends on who you are when and where you are standing.

You, yourself, are a stranger here.

*******

Nothing in There is Nothing Left to Say (On The Invisibles) is guaranteed factually correct, in part or in toto, nor aroused or recommended as ethically or metaphysically sound, and the same is true of the following recommendations we hope will nonetheless be illuminating to you, our most discriminating audience.

Evil Dead Trap.

Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers. Faderman, Lillian.

Angora Fever. Wood Jr, Edward D.