There Is Nothing Left to Say On The Invisibles

2.13

The Fanfic of the Book of the Movie

by Travis Hedge Coke

You know, how in the Sheman arc, Lord Fanny’s life is shown in genre lapping over genre – hardboiled Sin City crime, cute romance, ethnographic Believe it or Not!, Hernandez Brothers family drama, and in the same story, all King Mob has to talk about is himself as a mid-90s Liefeld caricature?

Take a deep breath and before you get to work, take another.

“Though you try, you can’t hide

All the things you really feel, this time decide”

– Stop, Look, Listen (To Your Heart), Thom Bell and Linda Creed

“Stop, look and listen

And always use your head

Look at the signal

Is it green or red”

– Stop, Look and Listen, Jimmie Dodd

The Invisibles is a toy box of tricks and games and action figures so robust they break into new toys, they bend into new games, rend into new laughs. It is enough to make you cry, but you can turn the pieces round and round.

Everything and everyone has inspirations, we all have models and use models and we do model and the best thing models can do is strike that good pose. The good pose will be replicated in magazines, videos, on bar walls, on kids’ posters, and school year book collages and head shop stickers and online store’s perfume bottles packaged in someone’s living room.

“Said I’m walkin’ on your side of the street (tellin’ me now, just walkin’)

I’m talkin’ to the people I meet (tellin’ me now, just walkin’)

Alright

Ha, hey”

– Walk, Don’t Walk, Prince and the Revolution

We replay and play our lives in genre-scapes. Don’t lie. Like contractions, like vocables, like gesture and tone, you do it, even if it is obviously pantomime, you do it. Blatantly affected? Of course you do it.

Aside the MeMePlex of The Invisibles or the divided mind, is Lewis Carroll’s Alice, who is able to be two people at once enough to box her own ears for cheating against herself in a game she played alone.

Shit or get off the top.

Spectrophilia splits and diversifies the light into component wavelengths so it can be appreciated. We are not entirely unartificial and we live in story.

We’re all often a lot of people.

Edward D Wood, Jr often lived as Shirlee, once a full-time public woman with a gendered occupation for more than three hundred and sixty-five consecutive days, yet popularized biography would frame her as “all man,” and “only a crossdresser” or having no gender dysphoria or queer gender celebration, only a fetish for a particular material often marketed to women.

Ed Wood is “the worst director of all time” not for his brilliant novels or her intriguing films but because a right wing, climate-change-denying, homophobic, transphobic shill said so for two deflating bucks in clout.

Some people have narrators in their heads, all the time. Others have no time, only static frames, ideas. Some people hear in sound. Some, think sound.

I can imagine a voice, but I have to imagine it.

Heterosexual was coined in 1869. Straight, in terms of sexuality or sexual engagement, from from the early 20th Century. Maybe one hundred years old as of this writing.

As with the argument that white people should not have to surrender racist or no-longer-acceptable terms for ethnic minorities, until after the The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People takes “colored” out of its name, “I’m not straight, I’m normal,” arguments are as specious as that use of, “normal,” is young.

At some point, linguistically, “normal,” moves from meaning a set standard – a thing to pursue – to as is, a natural state. Normal schools versus, “I’m not queer, I’m normal.”

Orlando and Xipe Totec are two names a little spirit takes, Invisible names, one culturally-specific and one ironic.

Together and disparate from one another, overlapping and over-erasing, Jill Thompson and Justine Mara Andersen make line and recreation of the marmalade guests of hunted history, the Romantics and celebrants such as de Sade and Shelley and Shelley and Maddalo and Lord Byron. Like Orlando, Mary is recreated, created, recreated, created with, I think, Andersen and Thompson her primary authors in that theoretical auteur way, not in collusion, but maybe at disregards with what the other lays down, as Thompson attempts to honor Grant Morrison’s inauthentic de Sade with soft lines of naturalism.

Virginia Woolf to Vita Sackville-West in 1927: “wrote these words, as if automatically, on a clean sheet: Orlando: A Biography.” Woolf knew the balance between truth and fantasy must be careful. A book about Vita cannot be a book about Sackville-West. A memoir must be written within one’s lifetime.

Pop art classicism redrawn rewritten by prescriptive and proscribing edits and time. The comfort of Andy Warhol’s Superman redraw is one of comfort in having comics on hand. The comfort of Lichtenstein copies is in their presentation as original thought.

The first two pages of Arcadia, a very early arc in The Invisibles, lays out what is for me, much of the anchor, weight, keel and rudder of the comic. Page one, a puppet play is performed for an audience, as an audience member comments on the dissolving of real and unreal we experience as we are presented with art and story. Page two, a physical page of a physical page of writing by Percy Bysshe Shelley, on death, love, art and hope, Julian and Maddalo: A Conversation.

Orlando, and all spirits, are Invisibles, too.

“I love images worth repeating, project them upon the ceiling

Multiply them with silk screening

See them with a different feeling

Images

Those images

Images

Those images”

– Images, John Cale and Lou Reed

If something resonates, if something stays in us or worries us, enlivens or educates us, it may be worth readdressing. It might be worth talking about. Sharing with friends. Sharing with enemies.

Like it or not, Andy Warhol’s Superman pieces are some of the nicest, warmest Superman pieces anyone has done, and they are copies.

Are King Mob’s Gideon Stargrave dreams copies of Jerry Cornelius stories? Maybe. But, the International Times’ Jerry Cornelius comics have racist jokes in them and The Invisibles does not.

Mob dreams, or hallucinates, or has programmed in his mind a life as a cod Jerry, a white fish in crushed velvet flares and never-ending pop significance. As he is tortured and questioned, this fantastical life comes to the fore, exploding out as answer to, “Who are you about?” and “What are you?”

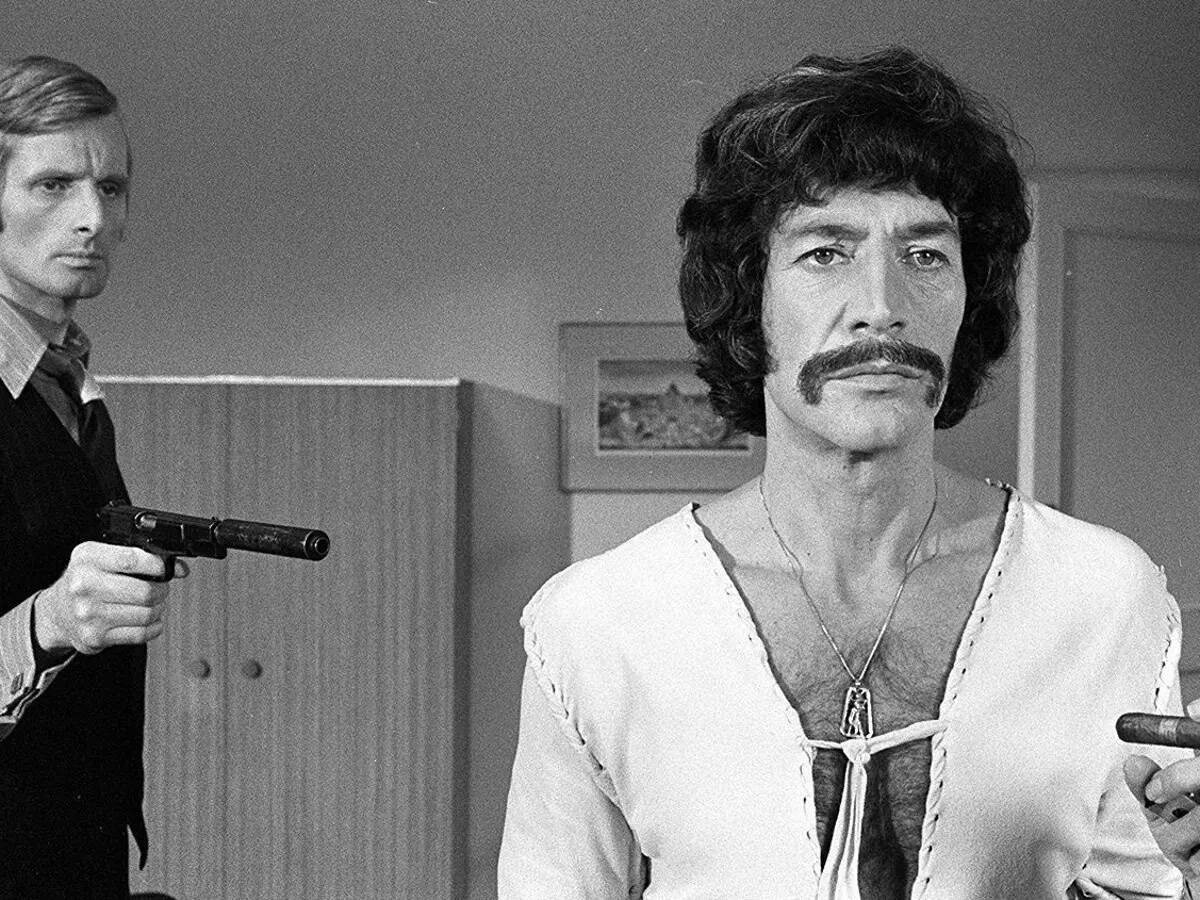

It is possible that Jon Six came into being, as an identity, a year before Jason King came into being, as a television character, on Department S, but Jason King is significantly based upon the style of his originating actor. Who borrows from who, how, when, is a matter of memory.

The TV spinoff for Jason King took his name, and Jason King, is a touchstone not only for Jon Six/Brian Malcolm/Mr Six, but the entire The Invisibles. As King debates over his own semi-autobiographical adventures with editors, with adapters, Jason King makes it evident that biography, autobiography, the biopic, the telling, retelling, and the barstool and pillow talk telling are all in all not the same telling, but the lived life is also a tell.

The fanboy, the fox, the Woolf, “Christ All-Bloody-Mighty,” the third police, in apocrypha, lion-headed belt, franchise badge, demiurge cheaters and platforms.

When Boy tries to self-explain her own young adulthood and family life, she veers to The Cosby Show and cops and robbers, gangsta and FBI dynamics rooted in television and movies and city stories.

“I’m scared if I write myself in,” says Ragged Robin to herself. “How many people have to tell a true story before it becomes true?” she asks herself. She says, “I’m scared if I write myself in, I’ll never get out.”

The comfort in a quarrel. Some sembling stone or light or names and like. Sometimes we spice our own life or put it into a sellable genre.

Mob and Boy and Jack Frost live in city stories, in urban legends. Sir Miles and Mr Quimper and Colonel Friday hinge on urbane legends, trade in traditional tales. (Quimper is taken off-board with Cinderella because kids understand Cinderella.) Ragged Robin and Boy live in their nerdy little spheres, sometimes quite literalized, with Robin in the ganzfeld tank, writing her fanfic. Irony and technique help Helga and Fanny keep a protective distance, the drag armor, the knowledge that a joke can save your life.

Fanny can live in slivers and venn diagrams of genre, but King Mob needs a genre at a time. When it is, “David Lynch directs,” for King Mob, it has to be, David Lynch directs. He has a James Bond mode. He has Gideon Stargrave.

It is funny, from the outside, to see Orlando strut around like a face-stealing peacock in his own personal horror movie. Mr Quimper playing lead in a pornographic waking dream. You could stall out the both of them with a boxset of slasher movies and a link to a bunch of hypno porn. Give Colonel Friday a flag to fold until he dies.

Fanny saw young that it is sets and set pieces. Fanny knows the puppet plays are real and that paper is made of paper. She knows that Orlando is a faceless, fleshless demon, but faceless, fleshless demon is a costume the air is dressed in.

Those white suits are hard to handle if you want to lock down to one genre. One mode.

They are brutal, all of them. Maya Deren movie silence producing keys and peace. Turbulence.

The Marquis de Sade and Tom O’Bedlam are ghosts, maybe, because they got too locked.

The white suit of John A’Dreams, Mr Dreams, Satan, Mr Quimper, Orlando, is an entry code, a signifier, your key and mine.

Characters who are beyond good and evil, like most people when we trot out that phrase, are brutal assholes. They are sadists.

The midwife of timespace, Billy “Brilliant” Chang, wears no white suit, though he performs a similar function, it can seem, to John. Billy is no asshole.

What “beyond good and evil” connotes, is our inclination to find absolution for others. Or, that the wearer is John in his timesuit outside the architecture of the comic. It does not denote anything. Connotations all the way down into ugly churning depths and somewhere down there is Mister Six saying, “Show me these bowels of yours.”

“Recursive loops,” is a concept and phrase, a technique and evocation, like, “time is a flat circle” and “the empire never ended,” which signal thoughts outdated as they are had, boring repetition, yet they also seem unavoidable. To bore is not only to illicit boredom. It can mean to drill into, to break inside, to make a hole in something.

When There is Nothing Left to Say (On The Invisibles) releases, someone’s going to tell me that the Ace of Pentacles is not related to the anus in any way. And, neither are connotative of xerography, fanfic, or nostalgia. They’re probably right. It’s still funny.

Always be boring. Never be boring.

It can’t rain all the time, says the little man from the Ty-D-Bol commercials. Did you know his name is Larry Sprinkle? A name he shares with a weather forecaster for WCNC, a Charlotte, North Carolina station? Like James Bond or Jesus, he was played by upwards of six different actors, over many adaptations.

When The Invisibles invokes or characterizes Jesus, he tells of the holographic universe, a playpen of light and touch like the holodecks on Star Trek and he has nails in him no mere buddha-nature kid like Jack Frost can pull out. Like James Bond, Jesus inspires hard man violence and cool posturing to get you through those rough and scary times. People in The Invisibles play at being Jesus as much as they play at being Bond. T’ain’t no sin in that.

It is a pride to play at Jesus’ nature, as it is to be a great James Bond. If embracing that Age of Horus vibe of the universe as a toy store, break some toys and light the walls on fire and they will be back in their boxes and forms for more play next time.

*******

Nothing in There is Nothing Left to Say (On The Invisibles) is guaranteed factually correct, in part or in toto, nor aroused or recommended as ethically or metaphysically sound, and the same is true of the following recommendations we hope will nonetheless be illuminating to you, our most discriminating audience.

Julian and Maddalo: A Conversation. Shelley, Percy Bysshe. 1824.

Superman. Warhol, Andy. 1961.

Superman. Warhol, Andy. 1981.

Tactical Readings. Pitchford, Nicola. 2001. Bucknell University Press.