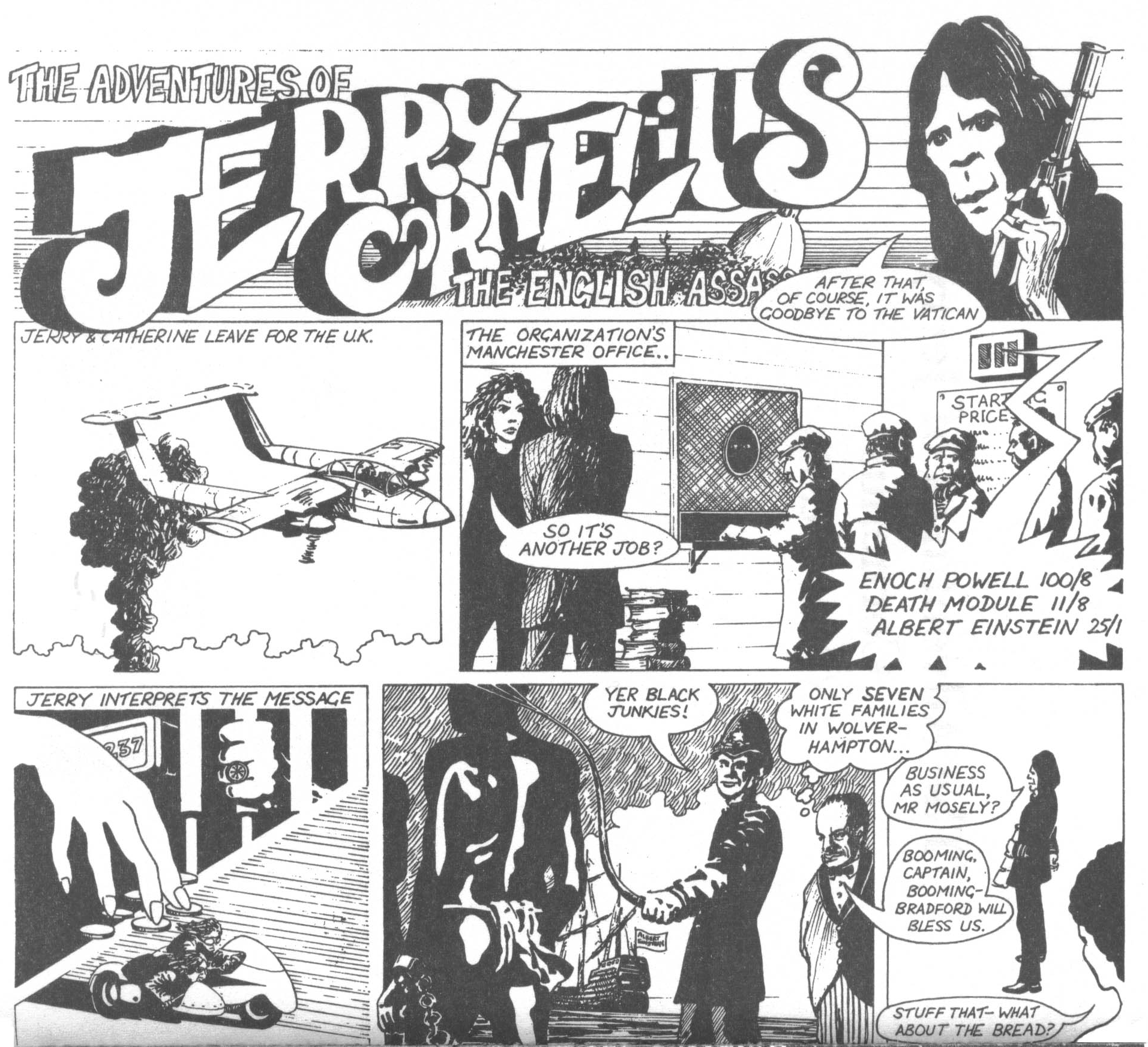

Michael Moorcock & Malcolm Dean, 1969.

Jerry Cornelius is not quite an open source character (though he has been used by others, with and without his creator’s permission), but Jerry Cornelius the technology, Jerry Cornelius the series of techniques or the tonal approaches, that may be something anyone can use. In degrees.

Patricia Highsmash

The Jerry Cornelius Technique

by Travis Hedge Coke

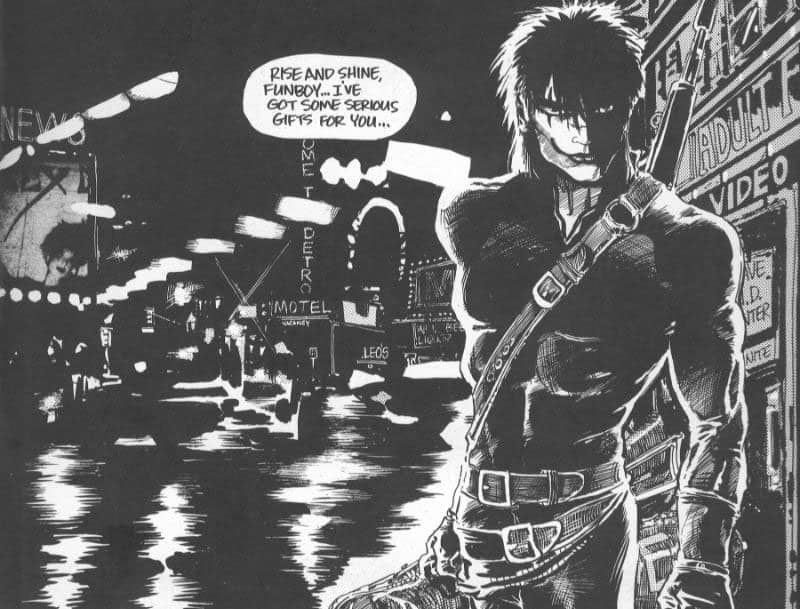

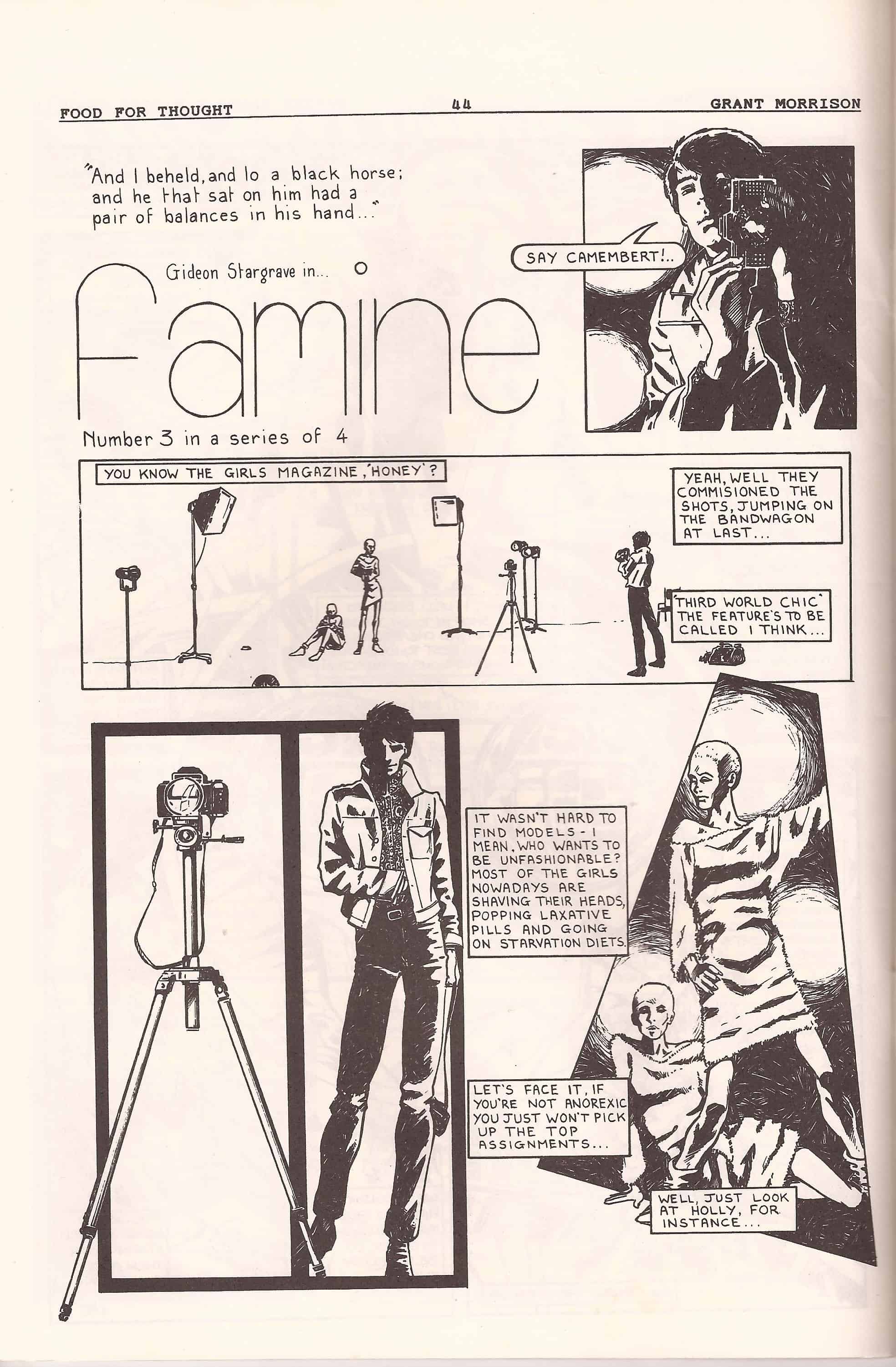

Jerry made his own comics debut in The Adventures of Jerry Cornelius: The English Assassin, at the end of the 1960s, serialized in International Times. James O’Bar’s The Crow, as comics and a film series, are Jerry Cornelius products. Every Prince comic and Prince movie is a Jerry Cornelius, including Purple Rain. Maybe most blatantly Purple Rain. Hawkwind songs; Monster Magnet albums; some of Grant Morrison’s earliest comics and some of his most personal; Buckaroo Banzai films, novels, comics; The Magic Christian; Rookwood.

And, here, the hump comes in, that we must get over: Jerry Cornelius is as much techniques applied to understanding stories, as to telling and shaping stories. Jerry Cornelius, the mode, is basically the 20th Century look, a look that was valid in the 19th and still a good look in the 21st. A codification.

James O’Barr, 1989-2011

At its simplest and most obvious, we see the rock’n’roll hero, humble beginnings, brilliant, musician, fighter, lover, a little prone to treat other people as pets or zoo animals, stylish, in love with rare instruments or techniques, misunderstood, and the stock characters surrounding them, who are simultaneously in earnest and farcical. They wield an idiosyncratic tool (the needle gun, the one of a kind guitar, the webshooter), use unusual vehicles, dress like no one but themselves. By the middle of the 20th Century, this was the protagonist, this was us, as individuals. Elvis in any Elvis movie. Elvis in any movie about Elvis.

This is what Moorcock calls, “Jerry as a personality,” in My Times, My Lives. “Too shallow to hold onto his miseries for very long,” but also too caring and maybe not wanting to be so caring. Eidolons like the protagonist of The Crow, Transmetropolitan’s Spider Jerusalem, Prince as the Kid (even Prince creating Prince to create the Kid) are emblematic of care disguised, for self- and world-protection, as disaffection. The rock’n’roll sneer is love.

The best Jerry, in this respect, is not even Jerry, not even in Moorcock’s own work, but Una Persson, because Jerry the personality is an anxiety that can be better served as world and story anxiety, not personal. Jerry the personality, as exemplified in Grant Morrison’s The Invisibles (which Moorcock does not seem to like and feels is plagiarism and alright), is an affectation, too. The poor little rich boy. Jerry, the personality, is classist from the inside. A class trap.

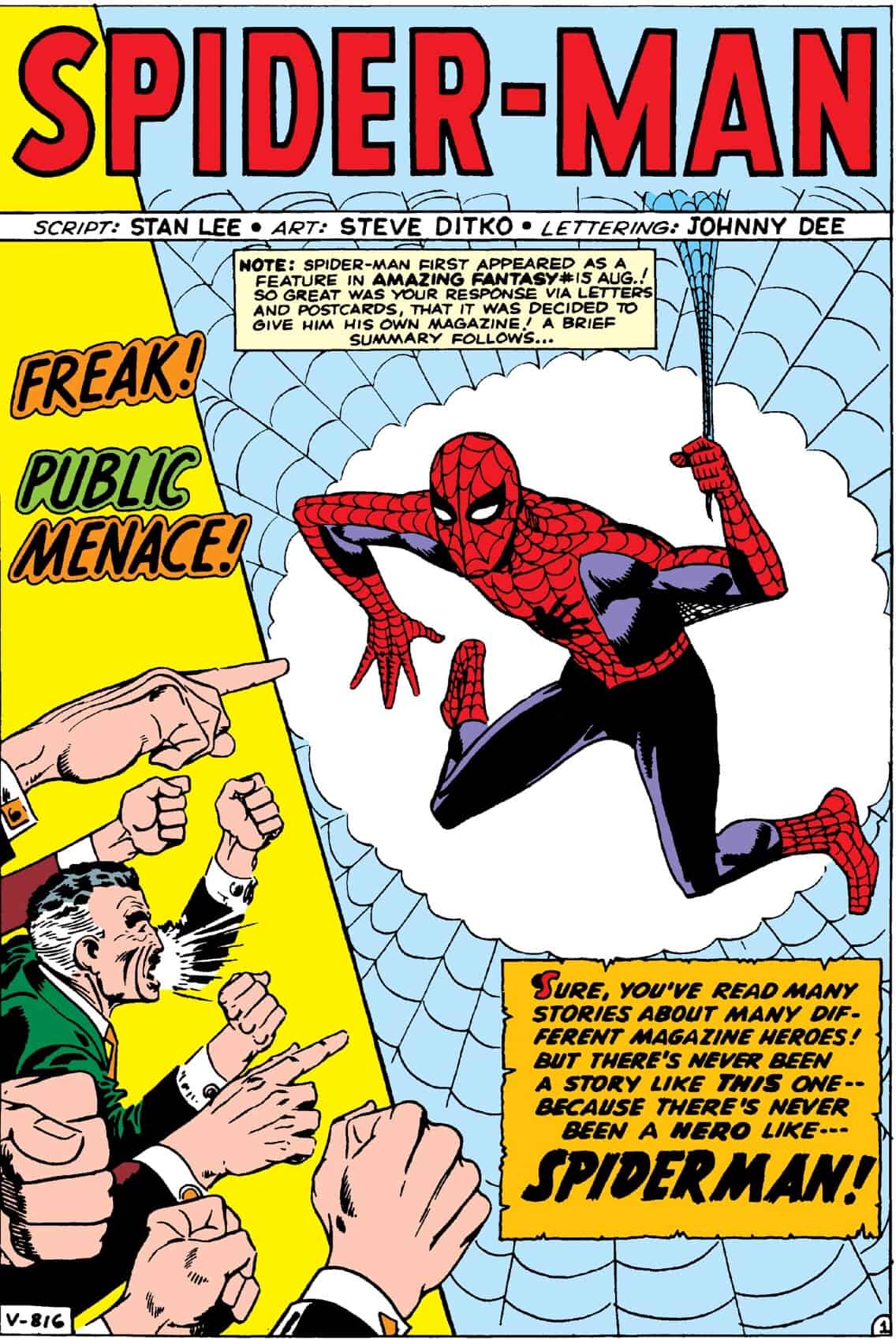

In terms of comics, especially, Ditko Spider-Man, with his specialized weapon and his sneer and snap at society’s ills and frivolities, is probably disturbingly more Jerry than either Peter Parker or Jerry Cornelius would be comfortable with.

Jerry as a technique, however, has less need to be a bear trap of classism or world edict.

“[A] form of exaggeration not dissimilar to Italian Commedia dell’Arte… methods which help us to deal more effectively in our fiction with the events and idiosyncrasies of modern life” (also, My Lives, My Times). There is a sense of pre-made familiarity in these methods, in the layout of these techniques, a sense of easy, ready interpretation, and also as many layers as we would like to find.

Steve Ditko & Stan Lee, 1963

Jerry as technique lets us look away from the vision of Peter Parker or his masked alter ego, at Aunt May, Betty Brant, Flash and Jameson, and see not only Parker the smart kid, Parker the hero, but Parker the temper, Parker the jealousy, the weasel profiting off the maligning of another (who is also himself).

This is the thing about going down rabbit holes. They lead down and they lead up, they don’t even really lead, they’re just there. Or, they aren’t.

“Cause, remember: No matter where you go… there you are.”

The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension