EDITOR’S NOTE: To mark the passing of Rachel Pollack, we are re-presenting our own Duna Haller’s loving tribute to Coagula, DC’s first trans superhero as created by Rachel.

‘You are real, aren’t you?’

Without a doubt, Rachel Pollack’s run in Doom Patrol is filled with gender imagination and exploration of human sexuality in every corner. The run goes as far as touching these themes in ways larger than life, dedicating the Teiresias War storyline (Doom Patrol, vol 2 #75-79, with the great Ted McKeever on art and colors) to an ancient conflict between the Teiresias and the Builders that serves as a metaphor and in universe reasoning for gender binary notions and the defiance of them always present in trans and gender variant people. But, this time I want to focus on the little things, the seemingly mundane interactions between characters, zooming in specifically in Doom Patrol, vol 2 #70-74, penciled by Linda Medley, with a rotating talent of inkers, colors by Stuart Chaifetz and letters by John E. Workman, Jr., where the Doom Patrol gang is introduced to Kate Godwin, A.K.A. Coagula, the first trans superhero to ever appear in mainstream comics, and Kate arrives at our house of weirdos and ghosts. And, while both parties clash in their particularities, is what unites them (and unites trans people with the very core of human diversity) what is attaching me to this story every day more.

‘We need stories. Stories feed us and keep us alive’

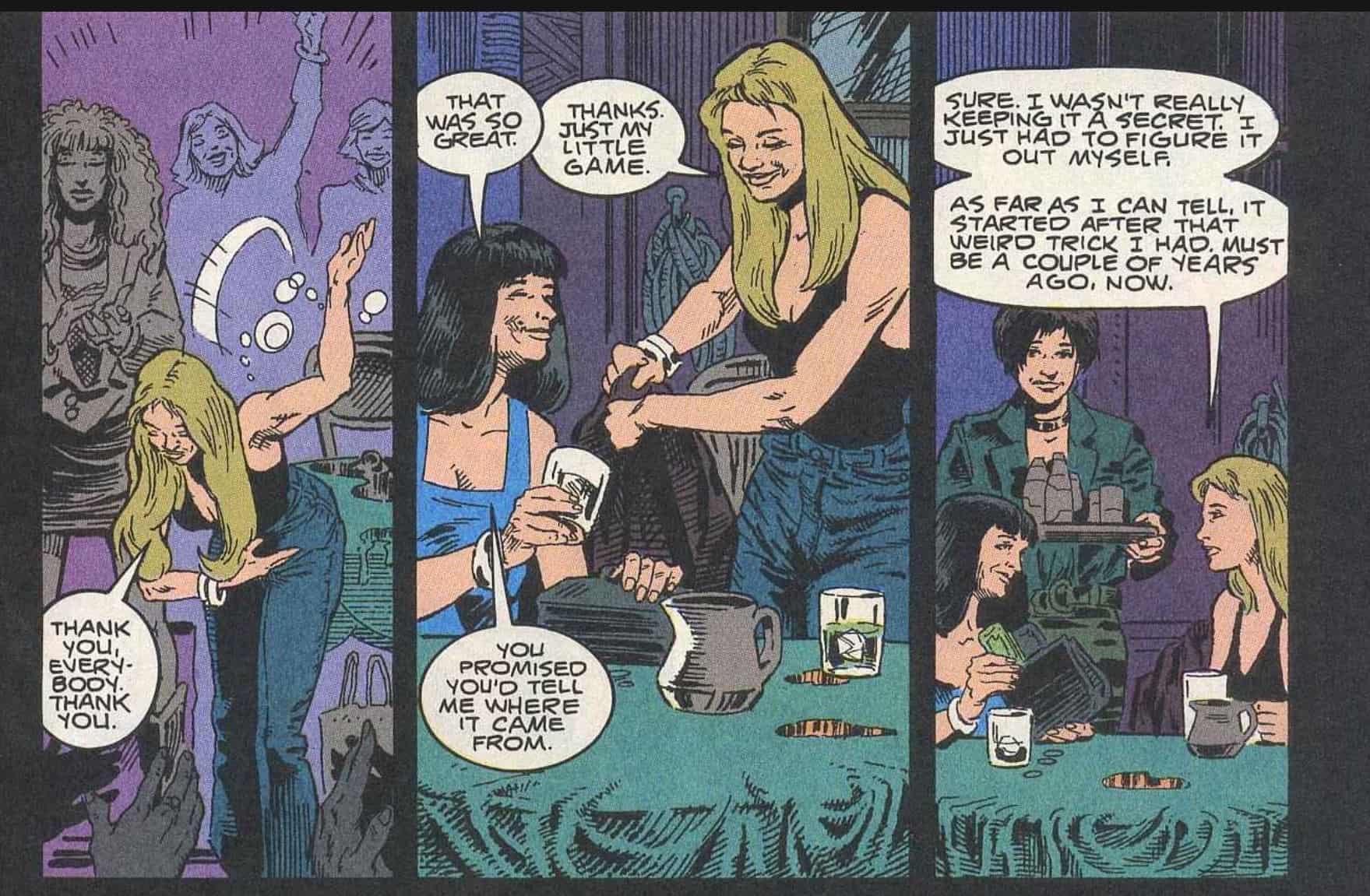

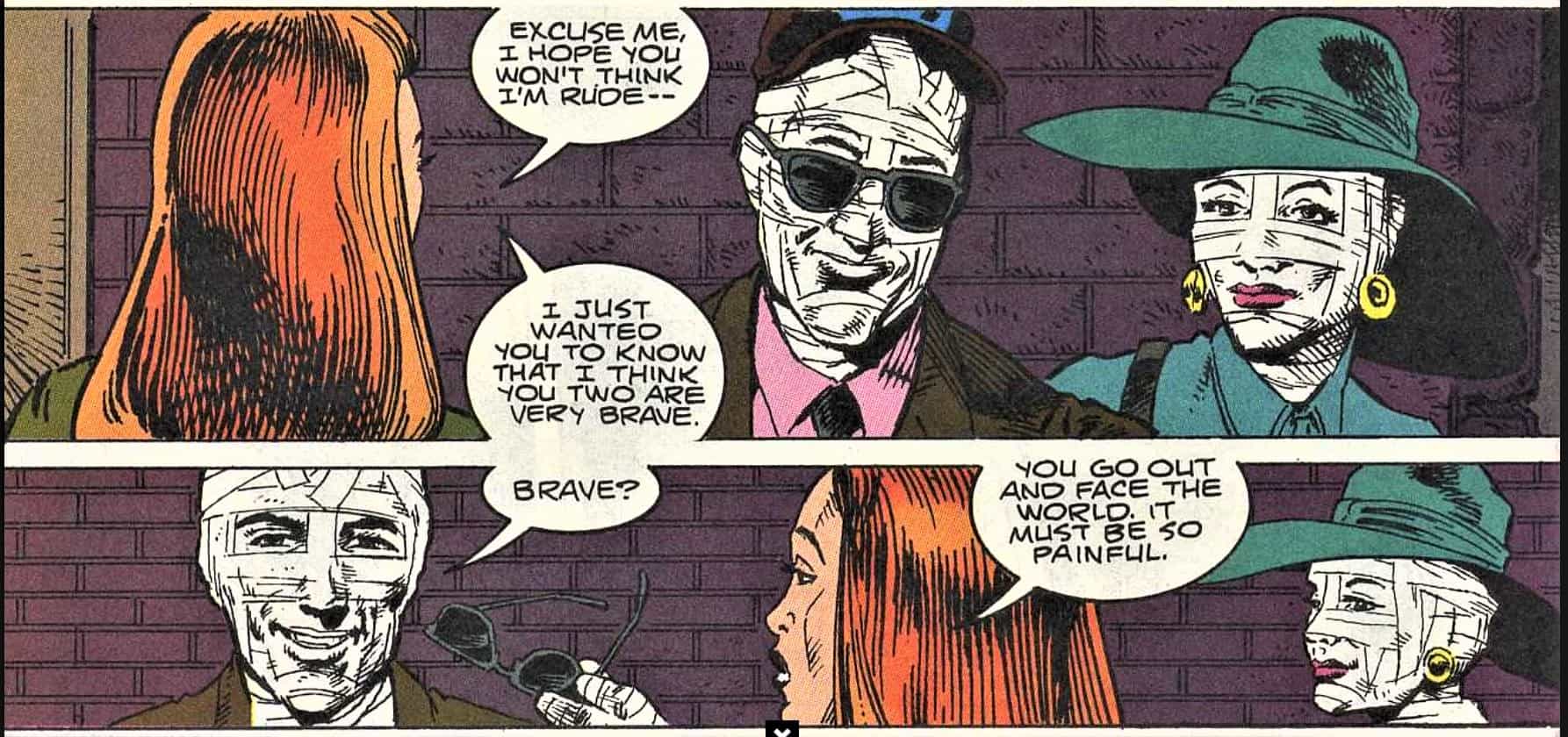

The introduction of Coagula is triumphant, yet simple: she impresses her old friends with her powers making a spectacle, and then she tells the backstory of how she got her powers while being a sex worker, related to Rebis (the non binary entity result of the merging of Larry Trainor, Eleanor Poole, and the Negative Spirit Mercurius) being a remarkable client. She is met by George and Marion, the Bandage People (who, coincidently, look a lot like Rebis to her), and brought to the Doom Patrol’s house. But this simple framing has a clear parallelism: when George and Marion go out in the world, Cliff, Niles and Dorothy seem apathetic to that outside world, and with a reason that has been cementing through most of Doom Patrol’s second volume: they are weirdos, they are stared at, pointed at, laughed at. They are dehumanized. Their bodies are spectacle and object. We even get a random bystander getting to George and Marion and telling them the tired diatribe that trans people are so used to:

‘Some boys have bodies and some just don’t’

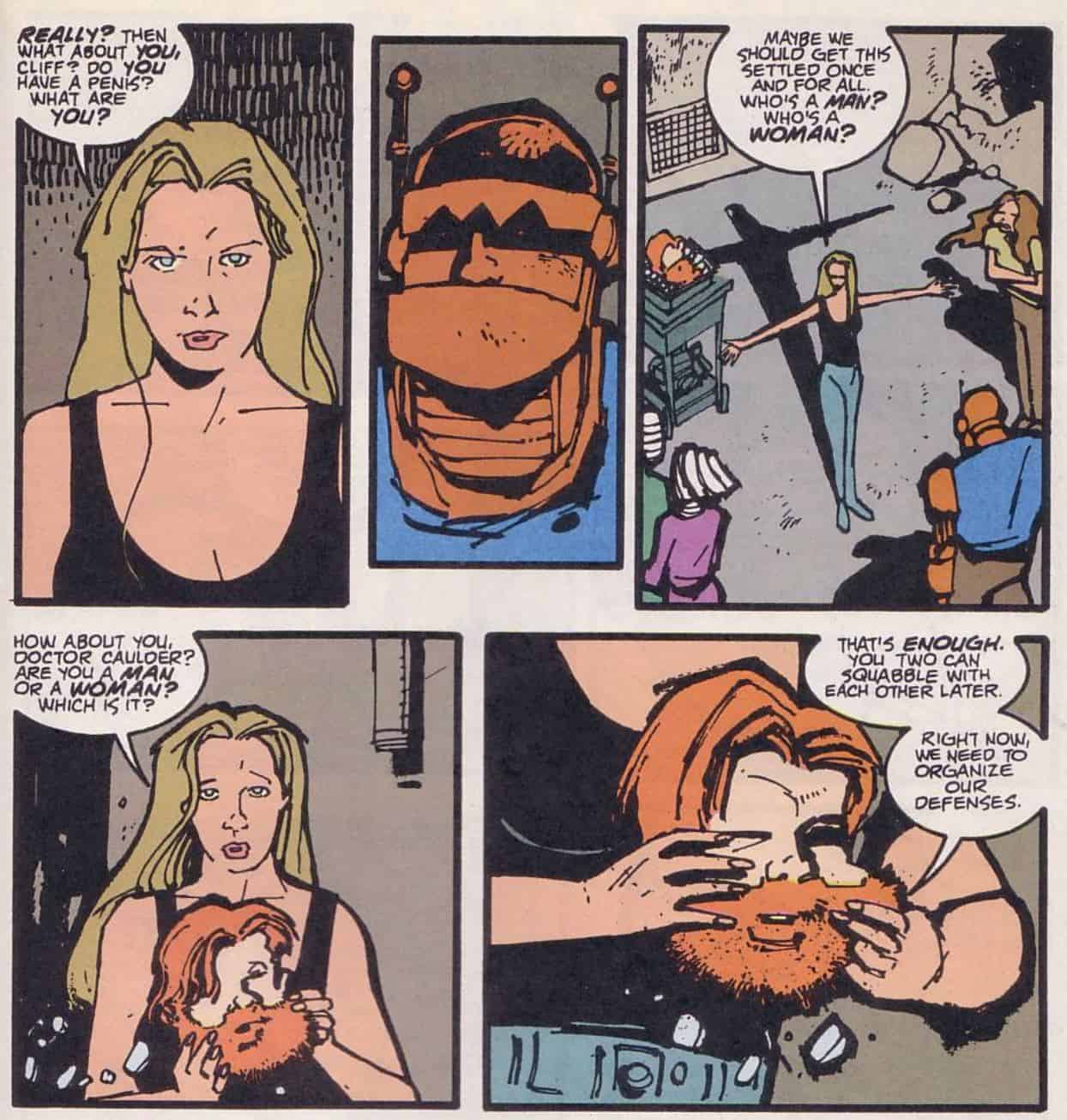

Pollack doesn’t hold back, however, in one painful truth about transness and allyship: sometimes the cis people that suffer the same harms that we suffer (gender non-conforming, fat, visibly disabled, cis women with facial hair) can be viciously transphobic and react to our existence with symbolic or explicit violence. Niles quite literally objectifies Kate’s body when he almost leaves her naked in what accounts, visually, for a symbolic sexual assault (not too explicit, a thing I appreciate), to then call her “surgically altered” in a despective way, and Cliff reacts to Kate’s existence in a similarly abrupt way, first seemingly retrospecting himself into a sadness bigger than life about his body, to then later – right before the Teiresias War climax arrives -, interject her with violent transmisogyny: “You had a penis, right? (…) In my book, that makes you a man” The Doom Patrol, for as much rejects and outcasts as they seem to be, don’t seem to grasp with how Kate’s existence as a trans woman turns one of the few things some of them were holding onto as one of the few truths that was still in their possession: the gender binary.

The rigidness of the gender binary permeates this introduction to our team, establishing a dialogue with the work that came before Pollack. Dorothy, an adolescent, menstruates, and that’s where her womanhood lies (in a weirdly racist storyline with redface imaginary that we probably didn’t need to see represented that way), Niles was bullied for not being “boy enough” and now he doesn’t even have a body to “sex up” (he is, quite literally, sexless) and Cliff sees the robotic nature of his body as a kind of androgyny that disconnects him from his own self-image, which in turn makes him want to get a “real man body”. The trans body works as a disruption, and comes with a wave of self-doubt and surrounded by a literal catastrophe that Kate seems to be the only one to really understand, in the complexity it creates for its surroundings. Which makes it even more cathartic when, at the end of the Teiresias War, Kate, Coagula, joins the Doom Patrol for good and begins to be a pivotal figure in the healing process of Dorothy and of Cliff.

‘Yeah, I know, it’s called “passing”.’

And it’s in the role of Kate in this story that the contributions of Rachel Pollack to the comprehension or trans identities (and to pop culture and superheroes in general) shine. The point is, Kate doesn’t shake the foundations of the Doom Patrol team and holds the key to the resolution of a large mystical conflict because being trans is some truth impossible to comprehend or to relate to. The reason is the complete opposite: trans bodies are an expression of human diversity, and the same gender binary that Kate has defied with her existence as a trans woman is the gender binary that tortures our main characters who can’t confirm to rigid ideas of manhood or womanhood. The liberation of Kate, the liberation of trans people, is closely tied to the liberation of everyone else.

In a particularly difficult moment in time for trans rights, as fascist rhetoric dressed up as feminism seems to permeate pop culture, academia and the discourse, I want to take this Trans Day of Visibility to look back at Rachel Pollack’s Doom Patrol as not only introducing DC’s first trans superhero, but shaking the foundations of every other character and showing us, in the details of this run, how necessary trans liberation and trans stories are for all non-normative bodies, but mostly because we’re human. And all humans deserve dignity. The weirdos, too.