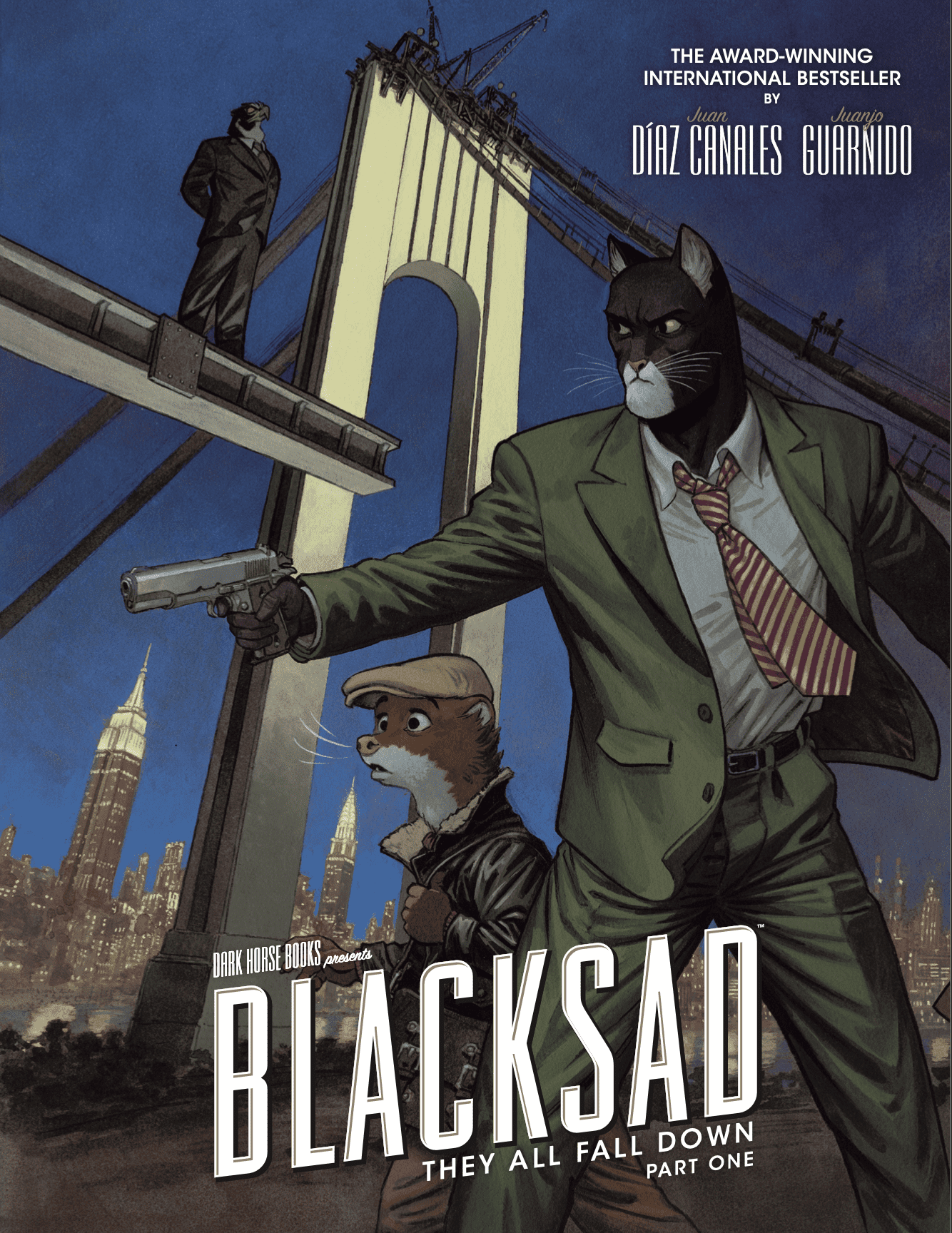

Following the release of Blacksad: They All Fall Down, Part One from Dark Horse, Comic Watch’s Lillian Hochwender caught up with the newest volume’s editor/translator Diana Schutz.

Comic Watch: So, Diana, while Blacksad is a series that’s been around for over twenty years, and Dark Horse has been publishing it in English for over a decade, how would you introduce the series to someone who may just be stumbling onto it for the first time?

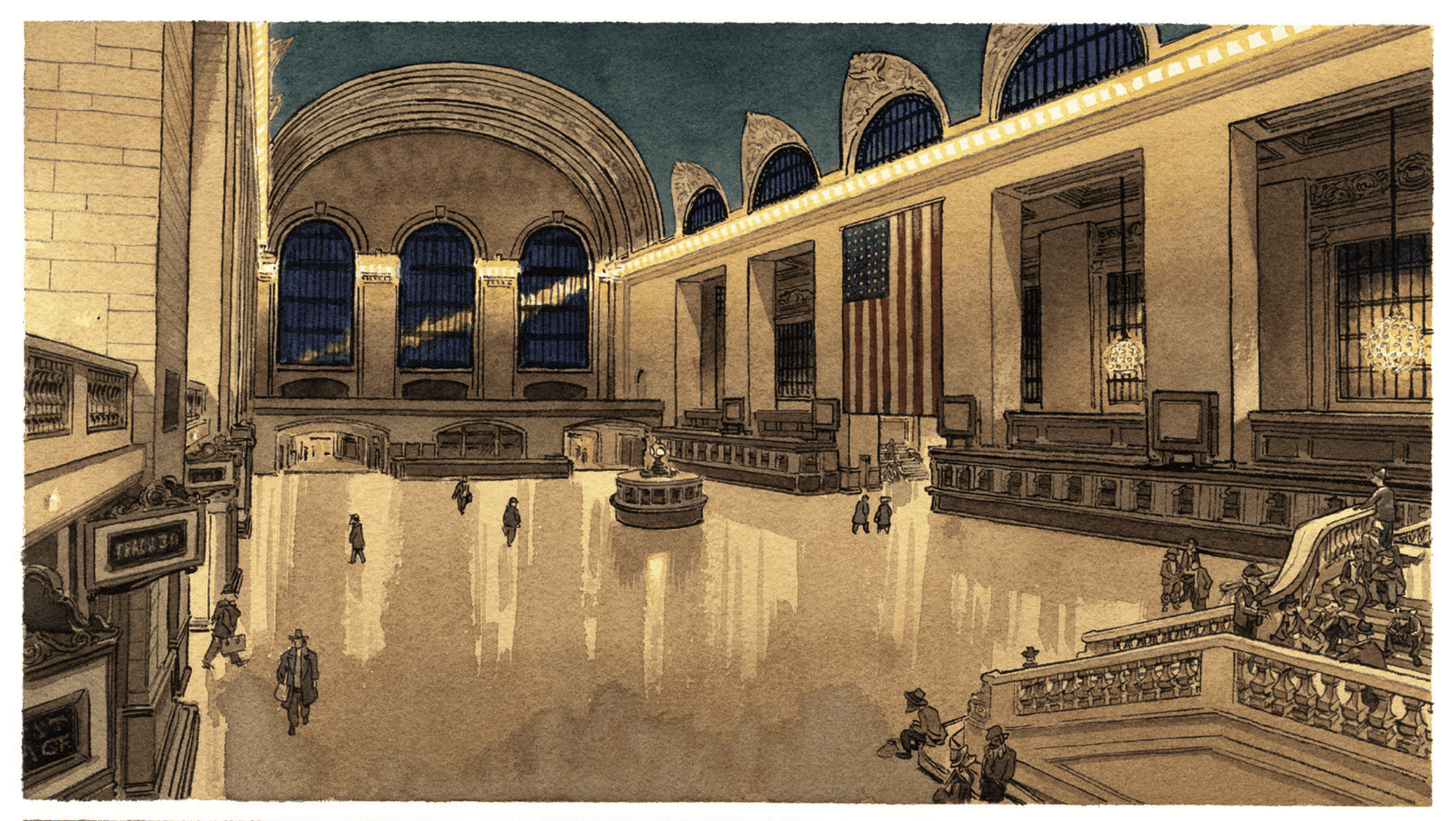

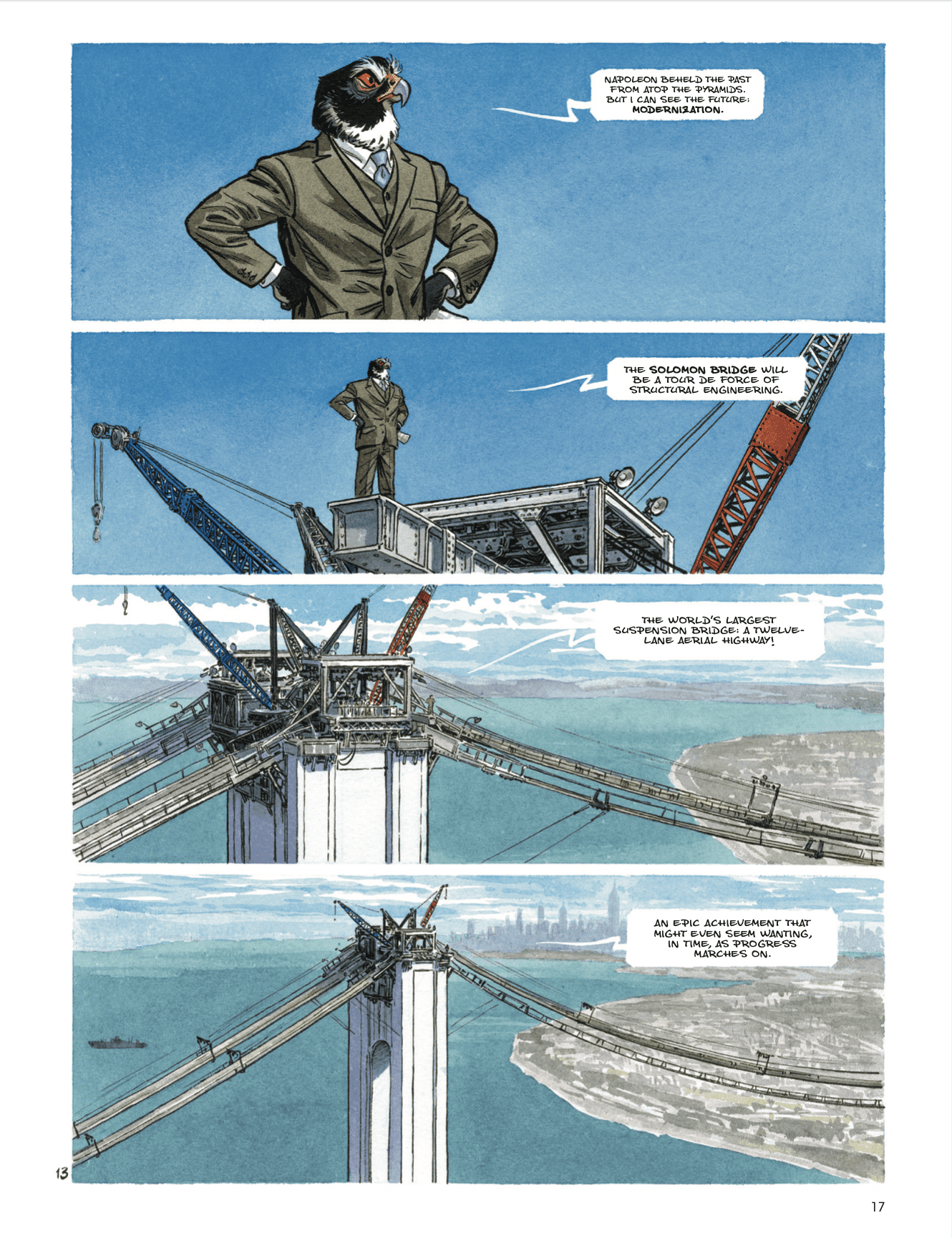

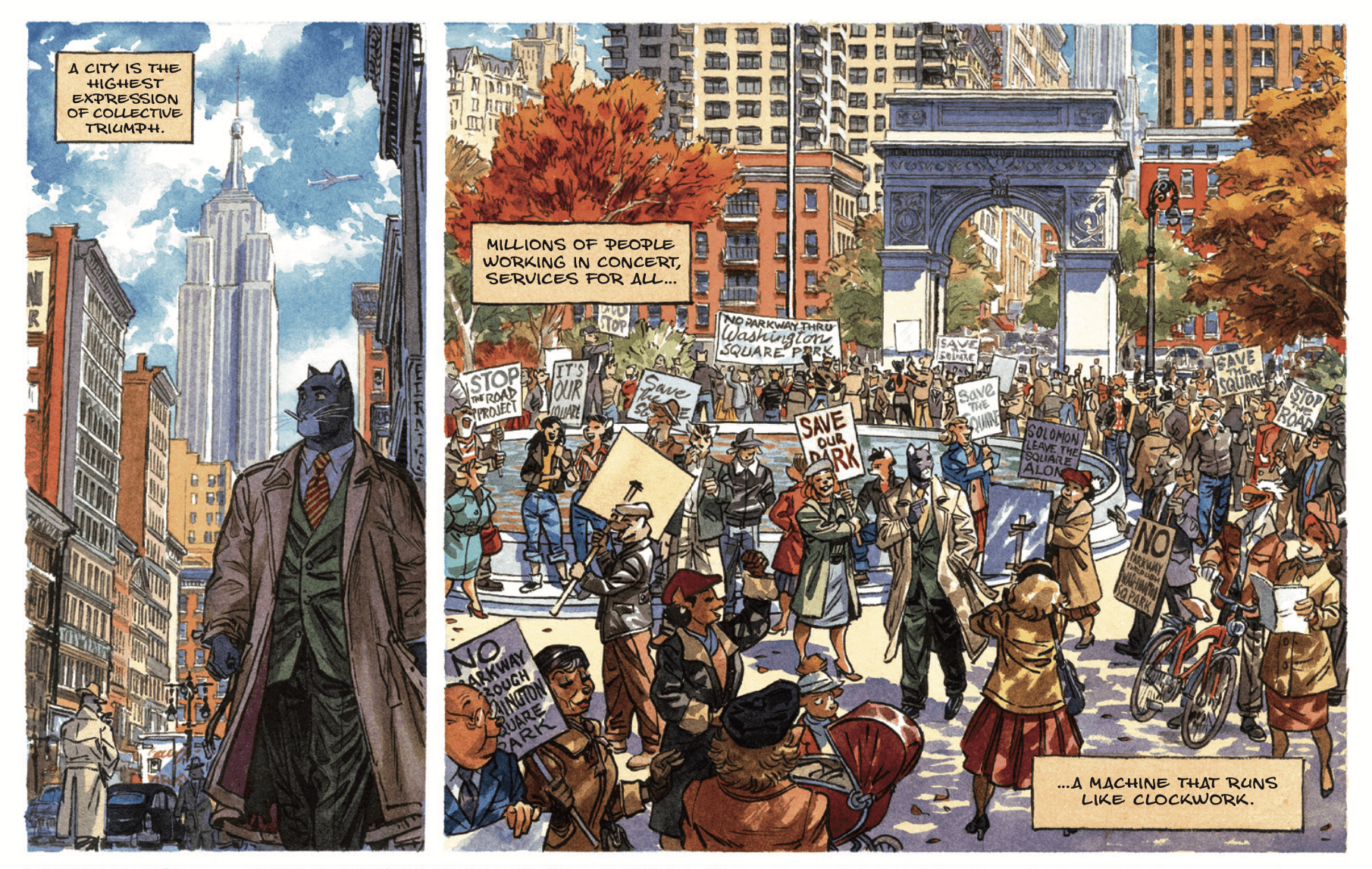

Diana Schutz: Blacksad is a complex anthropomorphic drama that appeals on many levels: crime and mystery, romance, social justice, and more. Perhaps Jim Steranko put it best in his introduction to the first volume: “Rather than animals who act like people, the [Blacksad] creators’ approach is predicated on people who resemble animals.” John Blacksad, of course, is the quintessential cool cat, but also the heart and soul—and conscience—of this 1950s noir series, one that, again echoing Steranko, is “an amalgam of traditional European comics storytelling and American cinematic style.”

CW: How were you first introduced to the series? What drew you to working on it?

DS: I’m a fan of that European approach to comics storytelling—certainly the slower-paced, complete-book model that came to us via the Franco-Belgian market—and I had already read, and loved, the two softcover volumes of Blacksad published by Byron Preiss in 2003–2004. So, I was delighted when Dark Horse acquired the license some years later, and in 2010, when editor Katie Moody left the company just after that first Blacksad reprint collection had been published, I specifically asked to step in as the book’s new editor. And with my background in Romance languages, it proved to be a great fit.

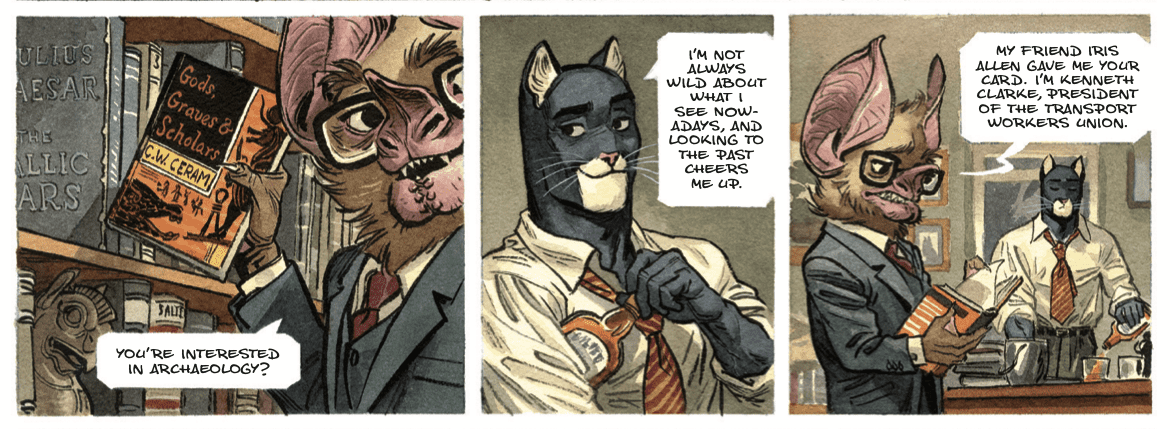

CW: The newest volume of Blacksad, the first half of They All Fall Down, focuses on the fraught relationship between the past and the future through its focus on midcentury industrialization. Early on in this volume, Blacksad tells someone that “I’m not always wild about what I see nowadays, and looking to the past cheers me up.” Translating Blacksad is certainly a form of looking to the past, as is reading it, but for you personally, what’s the appeal in media that looks to the past—if there’s appeal at all? Do you share Blacksad’s sentiments?

DS: Well, sure. Once you reach that point in your life when there are quite a few more years behind you than ahead, there’s a real tendency to view the past through rose-colored glasses, because your future possibilities necessarily become circumscribed. But I also think that, in general, age brings with it a wider perspective on history, which allows you to appreciate it—and its lessons—more than you might have been able when you were that much younger.

That said, I believe John Blacksad is speaking here in the voice of his creators. Writer Juan Díaz Canales and artist Juanjo Guarnido share a tremendous appreciation for history that is independent of individual age. Mind you, Juan finally turned fifty last September, so both creators are now past the half-century mark. But their love of 1950s Americana is precisely what drives this entire series, and the extensive historical research they both do for the book is evident on every page, conceptually and visually. Lewis Solomon, for instance, the “villain” of this particular storyline, is based on the real-life Robert Moses, an urban planner of questionable ethics. And while his career is now steeped in controversy, it’s important to understand that in the 1950s, growth was the watchword, whereas sustainability hadn’t even entered our vocabulary. This historical awareness adds dimension to Solomon—muddying up the waters, so to speak—and makes him more complicated, and therefore more interesting, as a character. And that speaks to the essence of good drama, fueled here by the creators’ attention to the past and its details.

CW: Speaking of the past: in 2015, you announced that you were leaving Dark Horse after having filled various editorial positions there for 25 years—and after working with some big names like Frank Miller, Neil Gaiman, and Stan Sakai, I might add—to focus on academic work. What factored into your decision to return to something that—at least externally—looked as if you’d left it in the past?

DS: Things change. But the answer is pretty simple, really: Juanjo Guarnido asked me to return to the book—as both translator and freelance editor—and I said yes. I love Blacksad, I love working with Juan and Juanjo, and Dark Horse editor in chief Dave Marshall, my erstwhile assistant and all-around great human, has created a really healthy working environment in the company’s editorial department, especially for women.

When I stepped away from Dark Horse staff in 2015, my goal was never to leave editing behind altogether—it’s too deep in my bones! But I wanted to create time for other kinds of work in comics, including academic work. Dr. Susan Kirtley was then in the process of developing an entire Comics Studies program at Portland State University, and I very much wanted to help with that, having taught comics courses myself every year since 2002. So, in the past six years at PSU, I’ve taught Comics History, Comics Theory, Comics Memoir, and the first-ever (anywhere! anytime!) university-accredited course in Comics Editing.

Leaving Dark Horse staff when I did also allowed me to serve as script editor for my brother-in-law, Matt Wagner, on the final third of his Mage trilogy, published by Image. My working relationship with Matt goes back decades: all the way to the ’80s! In fact, Mage: The Hero Discovered #6, published in 1985, was the first, or one of the first, comics I ever worked on as an editor. Returning to Mage—working with Matt and also with my nephew Brennan Wagner, who colored the new series—was a meaningful project that I wouldn’t have been able to take on as a Dark Horse staff editor.

However, I’ve continued to work for Dark Horse all along, but on a freelance basis since 2015, largely as a French>English translator . . . which brings us right up to your next question.

CW: After decades working solely as an editor, what drew you to translation? Though you’re notably also serving as editor for Blacksad: They All Fall Down—Part One, have there been any difficulties in transitioning from one role to another?

DS: The easy answer to your question is that translating fiction is fun. It’s challenging, too, and that makes for satisfying work.

There are also core similarities between editing fiction and translating it that aren’t apparent on the surface. To begin with, both require a first-rate command of English. Most people who understand only one language—which, by the way, includes most editors and publishers—don’t realize this about translation. But, for example, when the late Spanish>English translator Gregory Rabassa was asked whether his Spanish was good enough to translate One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez, Rabassa very smartly replied that the real question was whether his English was good enough! And that’s a telling point: as the translator, Rabassa had to (re)write García Márquez’s masterpiece in English, not Spanish. We write in the target language, not the source, and all the qualities of fiction—voice and tone and flow, character, metaphor—these are all functions of the specific language in which we’re writing. They don’t “translate” over from the original; they have to be written into the translation script. Which is to say that a translator must be a good writer, one who understands the best possible means of expressing a given story in a different language: English, in our case. This, incidentally, is why translators should always be writing into their own native language; in almost all cases, that’s the one we write best.

Similarly, editors are constantly called upon to write, or rewrite, authors’ scripts—to find what’s great about a script and, when possible, make that even better. As an editor of creator-owned work, as I was for the majority of my career, I wasn’t much involved in making up characters or plots; those were the givens, and my work with writers was usually at the level of script. And now, when translating French or Spanish comics, the givens are the same—characters and plot—but they’re presented in French or Spanish. What I do is adapt the script from one of those two languages into an entirely independent linguistic system—English, whose functional vocabulary, by the way, is about five times (!) that of French or Spanish.

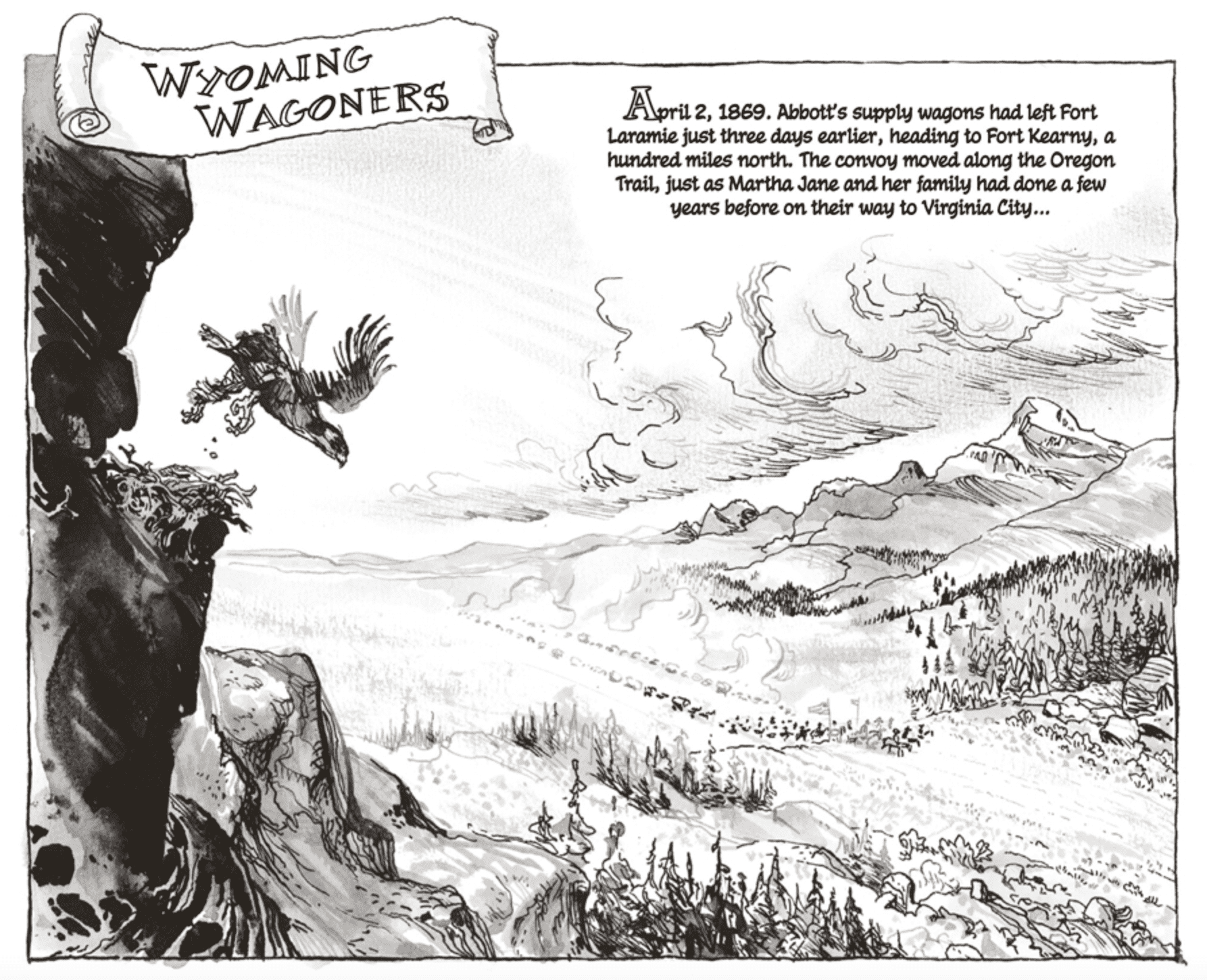

An editor is also a researcher and a fixer of mistakes. A conscientious translator will do the same, if she has time. When Brandon Kander and I were translating Calamity Jane for IDW, in preparation I read quite a lot about the real-life Martha Jane Cannary so that I could approach the work from a more informed perspective. But between the time that French author Christian Perrissin had written his original script, in 2006, and the time, ten years later, that Brandon and I translated what had become Perrissin’s three-volume French graphic novel drawn by Matthieu Blanchin, new historical information about Martha/Calamity Jane had surfaced, which meant that some of the original French script needed to be amended. Our editor on that project, Justin Eisinger, kindly put me in touch with Perrissin, who also kindly allowed me to make the English-language changes to his script that were in keeping with current research. As I’m writing this, it occurs to me that I probably bring my own longtime editorial perspective to my translation work, and that may not be typical of other translators.

For all its complexity, the work pays very poorly—even worse than editing. I’m willing to bet that most translators can’t afford to spend the kind of time I do. Unlike me, they’re trying to make a living at this job!

Taken from the English language translation of Calamity Jane published by IDW

CW: There’s a somewhat popular Italian turn-of-phrase often used in reference to translation: “traduttore, traditore” (“translator, traitor”), referring to the idea that all translations are acts of betrayal against their source texts. From that perspective, translation sounds like a losing battle in which translations can never hope to live up to their source material. What’s your perspective on “traduttore, traditore” and the role of translators in general?

DS: That’s an excellent question, meaning it can’t be answered in just a few words, but all translation necessarily involves interpretation. Does that mean it betrays the original? Renowned Spanish>English translator Edith Grossman explains that “fidelity should never be confused with literalness.” A so-called “literal” translation is a terrible, stilted, awkward read—which is never faithful to an original literary text. And because of that, because each individual language is an entirely separate system, there’s an important sense in which the translator is creating something new. Must create something new. We can call that a “betrayal,” I suppose, but I think most translators understand that what they do is a type of adaptation—like a novel to a film, but in our case, it’s from one language to another.

Generally, it’s translation scholars—not professional translators—who are paid to worry about this spurious “translator/traitor” dilemma. In fact, a translation doesn’t represent a loss so much as an addition to the original text.

CW: In your mind, what differentiates a good, or perhaps great, translation from a merely serviceable one?

DS: Well, the writing without a doubt. Understanding the source text is the easy part of the job. Conveying those clusters of meaning in another language—choosing the best possible forms of expression and making the best possible use of the target language’s own literary advantages—that’s writing. And that’s always hard. Some translators are better writers than others. Some have more time to spend. Considering how poorly comics translators are paid overall, most have to speed through their work just to pay the rent. I’m fortunate that I don’t depend on this work for a living. Of course, that also means I spend way more time on it than I probably should!

CW: In your translator’s note, you say that you reference both Juan Díaz Canales’s original script and the comic’s first editions (which are published in French by Dargaud) when working on your Blacksad translations. Could you share a bit about how that process works? And what it’s like coming on as translator for a series that has had translators before you?

DS: Translating Blacksad involves a unique situation because although Juan Díaz Canales writes the original script in his native Spanish, the “official” script is always the final, lettered French translation, in part because the book’s primary publisher is Dargaud; as the rights holder, of course, their edition is always the first to be released. And as Juanjo Guarnido is finalizing the artwork for each story, he’s also adjusting that French translation script in order to make the word/picture blend as seamless as possible. So, there are always differences between Juan’s original Spanish script and the final French lettered edition. Admittedly, those differences tend to be minor, but not always, and someone needs to pay attention to them!

As editor of A Silent Hell and Amarillo, I’d been working with a Spanish translator and revising her scripts in light of the final French versions of those books. But this time, I chose to go the other route: my partner, Brandon Kander, wrote the initial French>English translation, then I went back in over his first pass to write the final English-language script, with the French and the Spanish scripts as reference. Brandon and I both grew up in Montréal, where the primary spoken language is French. And I studied Spanish at night, here in Portland, for several years.

As for taking over the translation . . . well, at Juan’s invitation, I had already translated two short pieces for A Silent Hell back in 2012 and might even have done more had I not been working full-time as an editor in those years. And as the book’s editor, I was already pretty involved with its final scripts anyway. Part of what’s important to me about translation is a strong connection to the work and to the creators, so I hope I’m a good choice for Blacksad at this point!

CW: Are there any comics/graphic novels/graphic albums you’ve read in another language that you hope receive an English translation soon but haven’t had one yet?

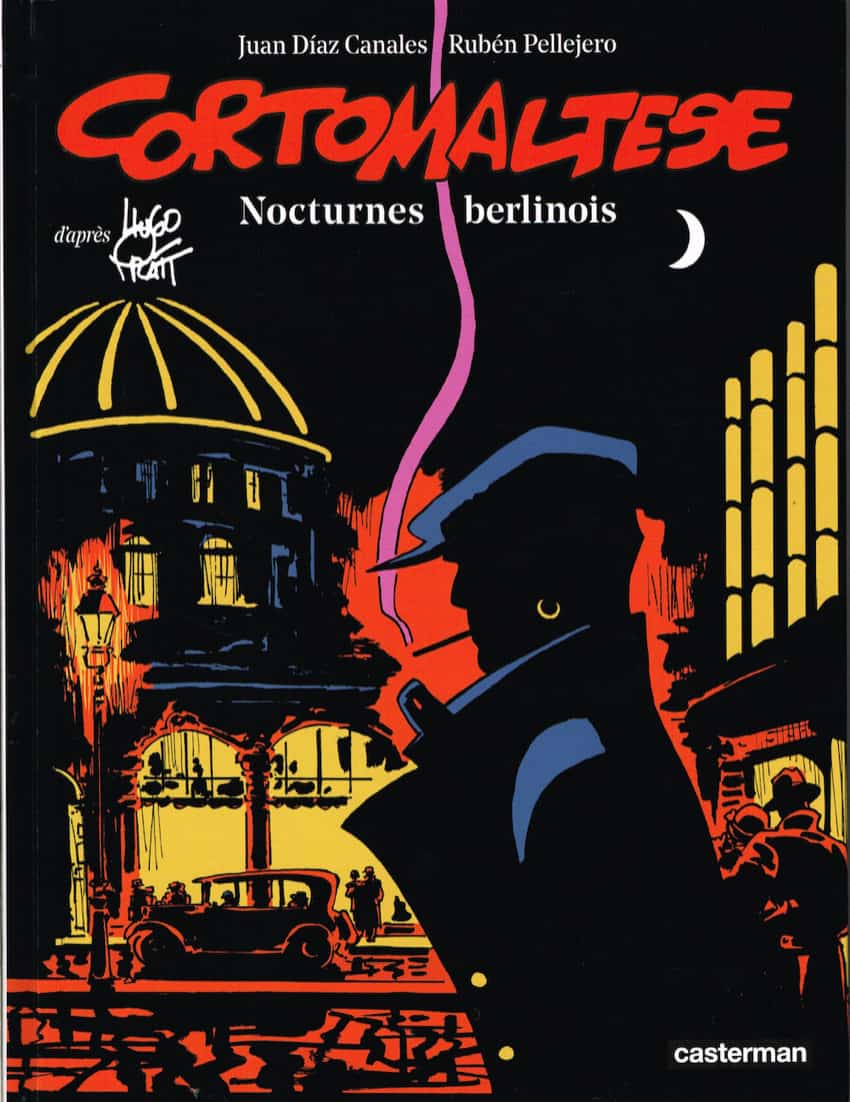

DS: You bet. Juan is currently writing new adventures of Corto Maltese, with the amazing Rubén Pellejero providing the art. Four graphic novels have been published so far—in color—and they’re gorgeous and fun, and I’d love to translate them! Corto Maltese is not just some obscure island nation mentioned by Frank Miller in Batman: The Dark Knight Returns. Frank was referring to the late Italian creator Hugo Pratt and his seminal character, the handsome adventurer Corto Maltese. Through his EuroComics imprint, Dean Mullaney recently published the entire run of Pratt’s classic Corto series, translated from the original Italian and beautifully reproduced in a series of high-end black-and-white softcovers. Pratt is a really tough act to follow, but Juan and Rubén are doing a fantastic job, and American readers are missing out at the moment.

CW: Looking to the future, what comes next for you? Does that future include Blacksad?

DS: Absolutely! Part Two of They All Fall Down is right around the corner.