Neither a commercial success nor a critical darling, X-Men: Misfits only lasted one volume, despite the backmatter promise of a followup comic. Drawn by an x-fan and long-time Marvel reader, Anzu (and her assistants), and written by Dave Roman and everyone’s favorite mega-selling comics author who superhero diehards like to forget, Raina Telgemeier, Misfits was a late in the game manga-fication of an American property by people who are largely, maybe entirely, not Japanese. Those are as much a grab bag as anything, but Misfits was incredibly good and had, maybe, only come a little too late to find a sizable audience.

In order to succeed, Misfits had to know who it was for and why, and commit to that. Which, it does. The art style and character designs are anything but generic or generic big eyes small mouth style, the characters are idiosyncratic and individuals, the comic provides a full story. Misfits is a complete and marketable package… that seems to have been dumped at sea and left to find a mama duck to imprint on.

Kitty Pryde, the protagonist of Misfits, and beloved don’t-call-me-plucky danger girl of the X-Men for almost half a century, is reworked here as a fresh new student enrolling Xavier’s, which is a full-fledged school with multiple classes and levels of non-adult students, with many traditional X-Men filling both superheroes and the school’s faculty, as per the Grant Morrison/Chuck Austen years on the mainstream X-Men comics. Kitty is fifteen in Misfits, as opposed to thirteen as in the original appearances, or her current young adult age in recent books, but she is still mildly cynical and also wildly naive.

The difference between Kitty’s naivety here, and in the mainstream books when she was first introduced, is that while she is the reader’s vantage point, in both, in those older comics, the adults constantly commented on what she misunderstood or her flawed tastes in clothes, boys, stowing away on planes flying into danger. In Misfits, the adults are far more detached, from Kitty and for us, as readers. This is not an X-Men team book, it’s a Kitty Pryde comic where X-Men have walk ons. And, so it is left to the readers to deduce when Kitty misreads a situation or makes poor choices, which she definitely does. We are both on her learning curve and expected to feel anxiety for her because we are at least slightly ahead of her learning curve.

“X-Men: Misfits aimed for mainly teen-girls,” says Anzu, and to that end, while there are less scenes here of grown men mocking Kitty’s fashion sense or threatening to spank her, her confusion over masculinity and toxic masculinity as divisible states, her naivety as to attractiveness versus goodness, and her role in the lives of the boys with whom she attends classes go right to the front. Kitty, in Misfits, is abused because she is uncertain in her gender and gender role, and because she is unequipped to understand or appraise masculine gender roles or even her own expectations of the behavior of men, women, girls, or boys.

The adult characters are not looking on her, as they did in the original Uncanny X-Men issues that told the original story of Kitty Pryde, as a sort of mascot or kid sister they were frequently babysitting, but as a student, removed from them as much as most students are from most K-12 teachers. At a boarding school with no other female students, this leads to Kitty having no one to really keep an eye on her, except for her classmates, some of whom are entirely predatory private school boys. They are no more knowledgable than Kitty, but they are more manipulative and they have numbers, meaning that they can reaffirm each others’ behavior, giving it the semblance of normality and thereby of correctness.

The only male student who exhibits a healthy masculinity, is Kurt Wagner, Nightcrawler, who says outright that he does not need macho gestures of a violent or explosive nature prove himself. That this is used to excise him from the cliques of his classmates does not faze him, and his reaching out to Kitty in a generous, but undemanding way, is a moment that would likely have paid off wonderfully in future volumes, had they been released.

That so many x-fans reviewing this or discussing it online seem to have missed clear points does not surprise me, but it should disappoint us all. Like x-fans who join comics hate groups because they dislike politics in comics or diversity in casts, it is weirdly not hard to locate fans of the x-properties who feel characters need to be hard and have sharp or shoot-y bits to rate. And, yet, also, weirdly, don’t believe male homoeroticism or male sexiness should exist.

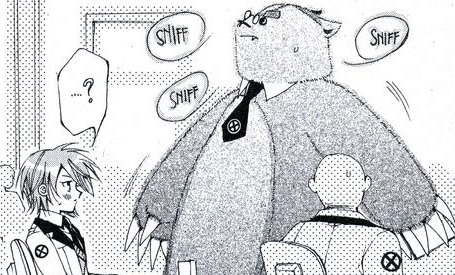

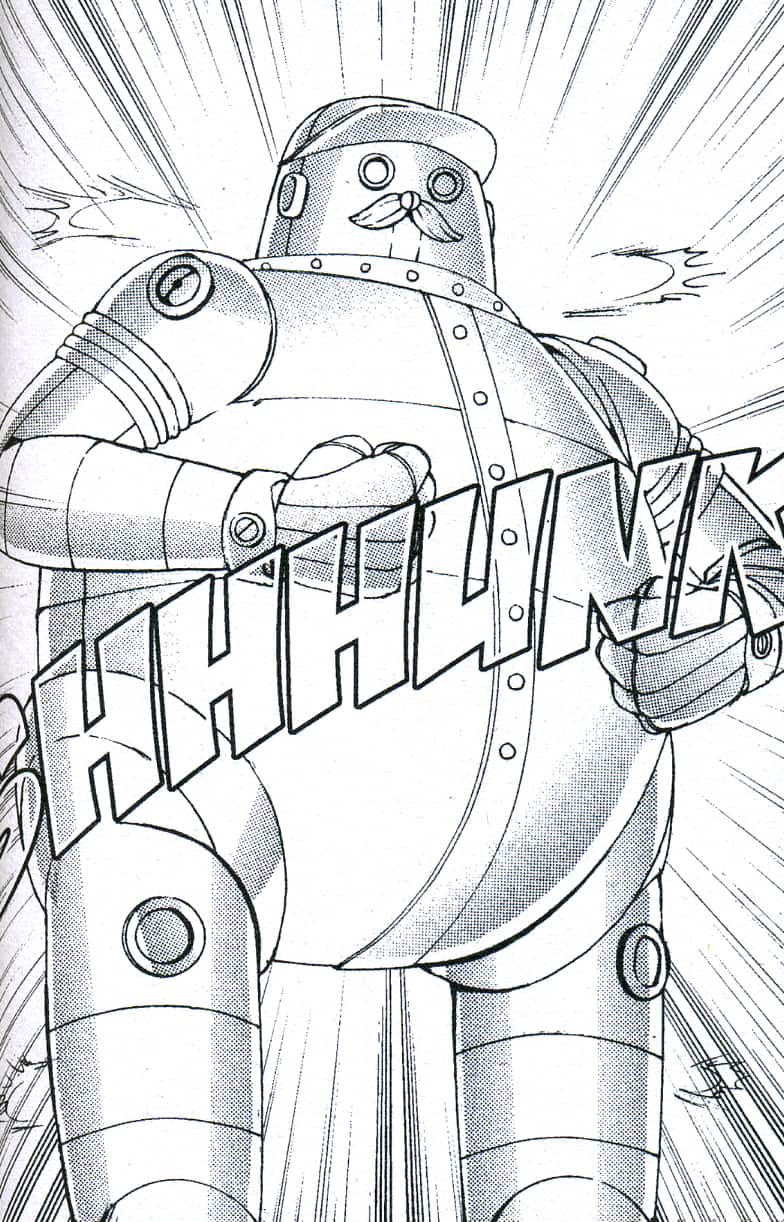

The adult X-Men having cartoonishly de-humanized forms even more in Misfits, include a barrel-limbed Colossus and a Beast who looks like an oversized plush toy. The adult world is almost turned unknowably alien, even the imperial punk Storm, leaving the kids to be both youth and the entire span of achievable society.

Notice this Colossus not romancing mid-teens girls.

Misfits is a gorgeous, twitchy book. Its anxiety of gender roles and the enervate noob vs upper class (both in terms of the school and economically/socially) fuel an inversion of boarding school hero formula: Kitty, by the end of the volume, is not the pride of the school and awarded genius. By the end of the comic, Kitty Pryde is overshadowed by even the potential of other girls attending (though obviously she could use the community and diffusion), and she thinks she has an awesome boyfriend while each and every one of us can see she definitely does not.

We, as an audience, whether we are teens, preteens, adults, regardless of gender, are set both inside of our heroine, Kitty, and around her as an observer and well-wisher. Misfits encourages some of the core conflicts of X-Men comics better than maybe any other version by displacing them from power fantasies or rewards of small acts of decency amidst grunting and posing. In mainstream/main-universe x-books, a superhero can join a genocidal supremacist cult one issue and in another issue be lauded as a gentle, wonderful soul. X-comics are set up to forgive extreme acts of cruelty and selfishness on the basis of “well, they also, one time, did something nice,” and that simply would not fly in the bounds of Misfits.

In order to succeed, Misfits had to know who it was for and why, and commit to that. Which, it does. Teenagers, especially shoujo-reading teenagers or teenage x-fans are primed to both enjoy this and get something of real value from it. In its way, it can be an antidote to something bad many x-comics carry along with their good. Misfits was, also, the original title for 80s gem, Fallen Angels, an ancillary x-comic that took from manga and Japanese culture and applied techniques and tropes to mutant youth concerns of the Marvel type. Fallen Angels also failed to produce a second volume, despite being loved, and the best efforts of the writers and artists involved.

Misfits vol 1 was on the New York Times bestseller list for weeks. Multiple weeks. Maybe it is only Misfits inherent contrariness to traditional x-books that left us without a second volume or more. I can only speculate, and Anzu herself, told me she has no idea why the comic stopped after one volume’s publication. “The second volume is already done,” she says, “but suddenly the publisher called off. It was never published.”