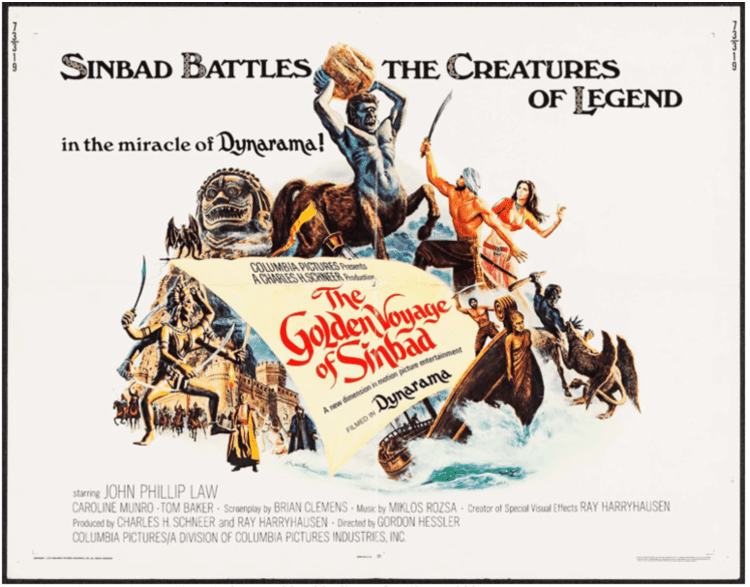

Harryhausen had been working in the special effects industry for decades and was often the first name mentioned when a movie needed them. However, the movie industry was changing. New technologies were being invented, new ways of telling stories were being utilized, and stop-motion was not as in-demand as it once was. Even so, Charles Schneer and Harryhausen approached Columbia Pictures about bringing back the character of Sinbad. It took some convincing but The Golden Voyage of Sinbad would be approved.

As with so many other films, this one began with sketches done by Harryhausen. They were used by Brian Clemens, who wrote the screenplay. Unlike other films, Harryhausen was given a co-producer credit for the additional work and greater involvement in the writing, editing, and even the casting process for The Golden Voyage of Sinbad.

To capture a kind of rugged terrain, the film was shot in Madrid, Spain. This made it possible to use the Royal Palace of La Almudaina, the Torrent de Pareis, and the Caves of Arta. Filming began on June 19th, 1972 and ran until August of the same year.

One of the more memorable sequences was the one involving Kali, the six-armed entity who fights Sinbad. The concept came from their original shooting destination of India. However, when shooting began in Spain, Harryhausen wanted to keep the sequence in. Much like the sequence of the dancing, multi-armed cobra woman in the first Sinbad film, this sequence involved Kali coming to life and dancing. To achieve this, a dance sequence was choreographed by Indian dancer, Surya Kumari. During the initial dance, she performed with one of her students strapped to her back. While this might sound strange, the visual gave Harryhausen a visual reference for the multi-armed creature.

Later, when confronted by Sinbad, the film’s villain calls upon Kali to fight for him. Much like with the dance sequence, this fight was choreographed with the actor and three stuntmen belted together. This provided a much more detailed visual for Harryhausen to animate each of the contact points for the swords. Each of Kali’s arms struck at a different target during the actual fight, they did not all move in unison as they did when Kali first began the fight.

Speaking of unified movement, viewers of Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith might see the influence this scene had on the animation of General Grievous.

Later in the film, a ship’s figurehead comes to life and attacks its crew. During one of the fight scenes, one of the crew slams an axe into the chest of the wooden figure. The real axe was thrown, then replaced with a miniature in the model. The seamlessness of the action kept the audiences wondering if what they were seeing was real or model work.

This was an example of what Harryhausen called, “contacts.” Contacts were moments in which the live-action actors interacted with the models. By Harryhausen’s logic, this interaction would make the audience believe what they were seeing was real. Of course, this had been done before in other films, like when Jason fights the skeletons or when the cowboys rope Gwangi. In The Golden Voyage of Sinbad, when the figurehead destroys a part of the ship, the “contact” was much bigger.

This effect was achieved by the entire set being rigged with wires which could be pulled, bringing it all down. Harryhausen then used rear projection and matting to align the figurehead model’s actions with the happening onscreen.

A clear difficulty with this film was one he had with Valley of Gwangi in which the color fluctuations and shifts in hues between frames made alignment difficult. Because of the use of traveling mattes and a lot of blue-backing, these kinds of problems were minimized. When The Golden Voyage of Sinbad had its Blu-Ray release, there are a few frames where this is evident. This could be the reason Harryhausen chose to do the work alone and in a rather hermetic setting.

The Golden Voyage of Sinbad was a success in the United States and Canada with revenue of around $11 million. Overseas, it did well but not what Columbia pictures would have liked. The film would be restored in the 2000s and John Walsh, a trustee of the Ray and Diana Harryhausen Foundation would say, “…since Ray retired, he’s become more popular. All those young people who saw his films in cinemas are now making films.”

Peter Jackson, Tim Burton, Nick Park, and George Lucas are among the long list of creators who credit Harryhausen as direct inspirations for them.

“Without Ray, there wouldn’t be a Star Wars,” Lucas has said.

To his point, without The Golden Voyage of Sinbad, the Fourth Doctor in the Doctor Who franchise might well have been someone other than Tom Baker, who played the evil sorcerer, Koura.

At the beginning of the 1970s, movie making was undergoing a change. While many in the film industry said Hollywood was going through an “artistic and financial depression,” others have said this was when many saw a rise in the same. Social change regarding free love, drug use, and even the music of the time caused a shift in movies. The collapse of the studio system would also influence how movies were made and the risks the remaining studios would and would not take.

At the end of the 1960’s, directors like George Romero, Stanley Kubrick, and Franklin Schaffner were making films like Night of the Living Dead, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Planet of the Apes. The landscape for what was achievable in film was changing. Because of this, effects for movies were also changing. Harryhausen, who moved to London in 1960, was known for doing all of the animation work himself without a crew or even a group of people to help. Still, he went on to do other pictures.

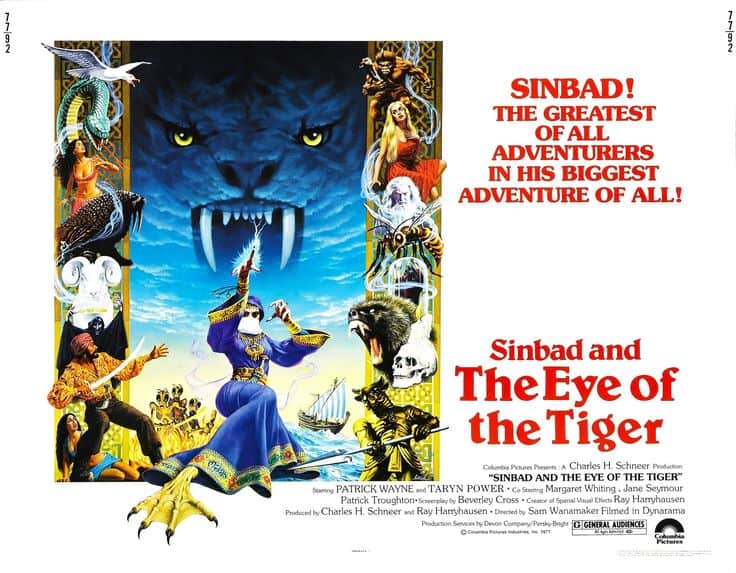

Although not part of the first two Sinbad films, a third film featuring the title character was made in 1977. Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger came about because of the success of its predecessor. Columbia Pictures began work on this film while The Golden Voyage of Sinbad was still in theatrical release. For this new film, more recognizable animals from the prehistoric era would be used. Producer, Charles Schneer hired Sam Wanamaker to direct because he wanted an “actor’s director” to elicit more dimensional performances from what he considered “cardboard characters.” Wanamaker would not be involved in any of the technical aspects of the film, although he had to be aware of them. As per usual, Harryhausen would handle all of the technical bits, himself.

In preparation for the saber tooth battle, Harryhausen shot footage of live lions and tigers to get their movement. Each frame of the tiger was animated, as with any of Harryhausen’s other models, but more care had to be taken with this one. Any movement could ruffle the fur in such a way as to disrupt the flow of the sequence. Any glitches in the sequence, Harryhausen credits to his having to answer the phone or otherwise be taken away from his work.

An example in which the animations heightened a character’s story was in the case of the prince-turned-baboon, Kassim. Overall, the film lacked any real character development on the part of Sinbad. However, the plight of the prince was moving. In the scenes in which the prince was caged, the movements of the baboon model had to exhibit animalistic features. In the scene where Kassim played chess with Farah, the model had to exhibit human traits which told its true origins. Because of the amazing work done for this scene, even the film’s harshest critics have lauded this scene as one of the film’s best.

In this scene, the baboon, upon seeing its reflection, weeps. This personal touch to a singular character was what set Harryhausen apart. Attention to this kind of detail was what made him such an artistic technician. While so many of the special effects of the day were done by large crews, this is the one time where one man, working alone, had its advantages.

This advantage would also be one of the things which would sideline Harryhausen in the future.

Realism was often a problem for many of Harryhausen’s models. To get the most from the sketches which were the basis for a lot of his films, he would pass them on to other artists hired to work on them. Their detail made the work easier.

“When you work with Ray, you’re absolutely sure of what you’re doing,” Colin Arthur, makeup artist on Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger, said. “It comes from his drawings, drawings that I, as a sculptor, could reproduce in full size. His work is so accurate in conception, so there’s no ambiguity…”

Ambiguity would work to the animators’ advantage when it came to the more supernatural beings like the cyclops, the saber tooth tiger, and the troglodyte. When dealing with the more human elements, like the model of Raquel Welch in One Million B.C. ambiguity could be utilized due to camera angles and the proposed perspective of a scene. Details would not matter so much. In the newer films, with filming and effects improving, special effects details would become much more important.

“There’s something that happens with stop-motion,” Harryhausen said. (Ray Harryhausen: Special Effects Titan, a documentary) “The model is strange. It gives the nightmare quality of a fantasy. If you make fantasy too real, I think it loses the quality of a nightmare, of a dream.”

Many agreed, Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger would illustrate this idea of the strange model and the nightmare/dream quality being integral to the success of the animation. The pitfalls of stop-motion animation lie in the tools, themselves. If a model is nudged between takes or a camera glitches, hundreds of hours of work vanish. Harryhausen’s solitary work ethic also meant, should any of these things happen, he was the only person capable of redoing the scenes.

Dennis Muren, Doug Beswick, and Phil Tippett would all be entranced with Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger. Muren said he saw the film eight times in theaters. Beswick was so inspired, he made his own version of the film, which he called, Phantom Island.

Tippett said, about the cyclops entrance, “From that point on, I gradually found ways of appeasing my needs to see this kind of stuff by making it, myself.”

All three of these creators worked on the original Star Wars film in some sort of special effects capacity. Muren went on to work on Terminator 2 and Jurassic Park. Beswick worked on Aliens, Dark Man, and Ghostbusters. Tippett served as creature supervisor for Jurassic Park and Starship Troopers.

In 1981, MGM studios would give Schneer and Harryhausen an expanded effects budget and name actors to produce Clash of the Titans.

Signed onto the film were Burgess Meredith, best known as the Penguin from the 1968 television show, Batman, Jack Gwillim, who played King Aeetes in Jason and the Argonauts, Siân Phillips, who would portray Reverend Mother Gaius Helen Mohiam in Dune, Ursula Andress, famous for her role as Honey Ryder in Dr. No, future Hogwarts professor, Maggie Smith, Harry Hamlin, who received his first Golden Globe nomination for Movie Movie, and Laurence Olivier, an accomplished stage actor who played Zeus, king of the gods.

Before MGM agreed to the project, Schneer took it to Orion Pictures, who wanted Arnold Schwarzenegger to play the lead. Schneer refused, as Perseus involved a great deal of dialogue. The roles of the gods were given to better-known actors on the hope the film would do better at the box office. All of the scenes involving the Olympians took just eight days to shoot. Meredith was cast because he was a well-known American actor and MGM wanted him so they could assure the public, this was not an English film.

Writer, Beverley Cross had the idea for the film and wrote the screenplay. Cross also wrote the screenplay for Jason and the Argonauts. In 1978, a copy of the script was submitted to the British Board of Film Classification, including scenes in which the Kraken would tear Pegasus to pieces and Andromeda would be nude at the peak of the film. Changes to the script included removal of these two points and a revision on Perseus’ battle with Calibos.

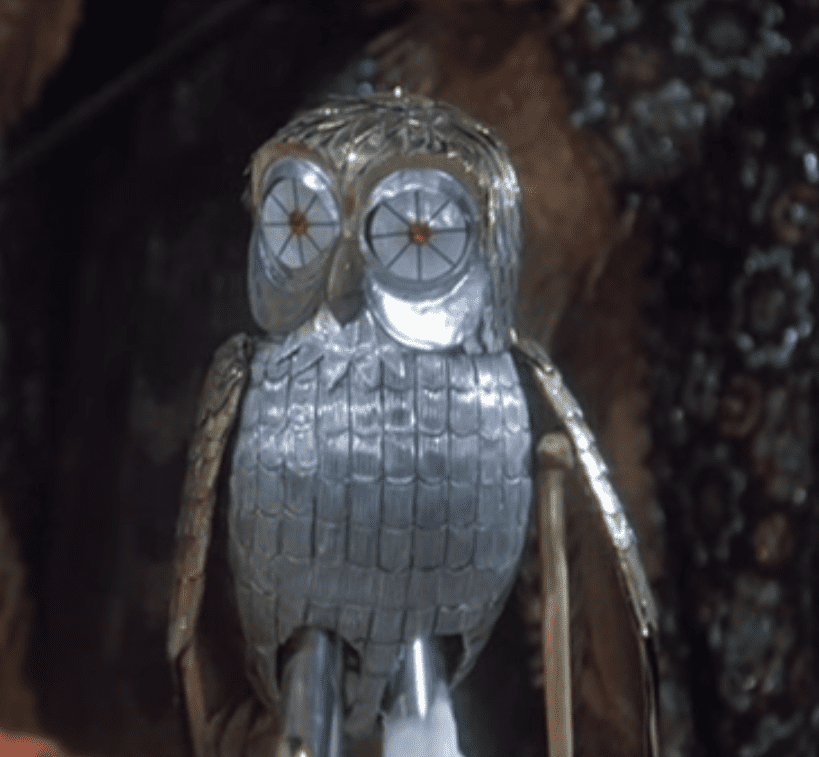

For this film, Harryhausen created Calibos, Pegasus, giant scorpion, Dioskilos, the mechanical owl, Bubo, the Kraken, and the hideous Medusa.

The Kraken was a combination of creatures, as there was no such creature in the original myth of Perseus and Andromeda. As with other creatures, he created the kraken was based on sketches he did.

Harryhausen wanted Medusa to be without clothes so he gave her a reptilian body. This was because he did not want to have to animate flowing cloth in addition to the twelve snakes on her head and the large coil of her lower body. The snakes and the coil/tail had to be moved in every frame to keep the fluidity of the figure believable. Medusa’s blue eyes were the eyes of a baby doll and were moved around with the eraser of a pencil.

Unlike other films, Harryhausen had to hire other people to help with the animation tasks. American animator, Jim Danforth and English animator, Steve Archer were brought onto the project. Danforth did a lot of the work on Pegasus while Archer did the majority of the work on Bubo.

“It was just extraordinary how much time it took to light (Pegasus). Forget the animation, just to light, because they had to hide all the wires,” says John Landis, director of American Werewolf in London. “I was there four or five hours, they probably got two or three seconds of usable footage.”

The effects for this movie were some of the best Harryhausen produced. Clash of the Titans would be nominated for a Saturn Award for Special Effects. In spite of this, MGM passed on the proposed sequel, Force of the Trojans. A major concern for the studio had to do with the growing caliber of computerized special effects and for groups like Industrial Light and Magic, who could do in a few days what it would take Harryhausen months to do.

With the rejection of a sequel to Clash of the Titans and the changes in technology, very few projects were utilizing stop-motion in the way Harryhausen used it. The sword-and-sandal film would prove to be his last film, even thought he would go on to serve as an uncredited consultant for the 1998 remake of Mighty Joe Young. He even had a cameo in the film.

“Young people have been brainwashed by television to want everything quickly,” Harryhausen said. “I felt it was time to retire. I felt I’d had enough.”

This year marks what would’ve been the 100th birthday of the man, the legend, Ray Harryhausen! Thanks for joining us in our tribute. Next week: A Fantastic Voyage To The Bottom Of The Shower: A Space Odyssey!